“Sea Oak” is a satirical, supernatural short story by American author George Saunders. Read it in the December 20, 1998 edition of The New Yorker.

“SEA OAK” IN A NUTSHELL

An extended family lives in a subsidized apartment in a dangerous, low-income part of town. Bullets regularly come through the window, but the Aunt is just glad they never hit anybody.

One day an intruder scares Aunt Bernie to death, literally.

After Aunt Bernie’s burial, the family learns that Bernie’s body has up and gone from the grave.

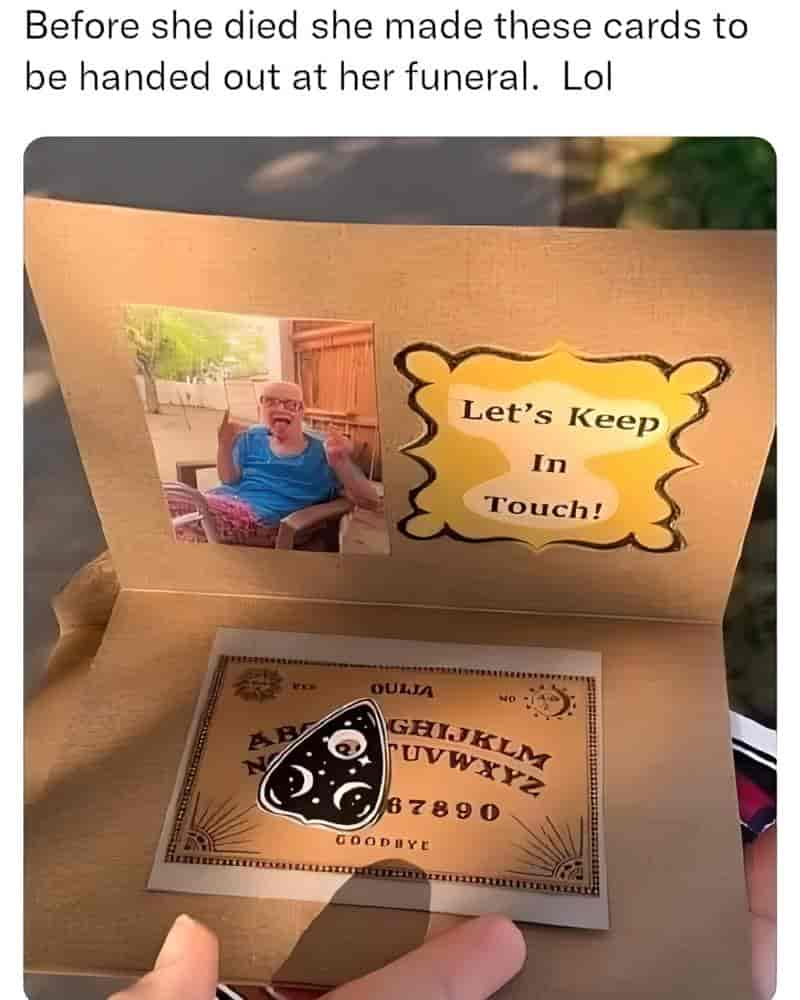

Next she shows up back at the house, sitting in her rocking chair, covered in dirt. She has instructions for the man of the house — the unnamed narrator — who works as a stripper. He needs to earn more to get the family out of the neighbourhood. First he needs to earn more stripping by showing all of his body, then eventually he’ll have enough to study law at community college.

The ghost of Aunt Bernie explains that she will use her super death powers to help the narrator out. If she knows a woman wants to see his peen, she’ll press a thumbprint into her forehead. She has also changed personality. No longer meek and content to put up with not much, now she is doing something about her lifelong virginity. Death has given her a revelation. She’s started swearing like a sailor.

At work, the ghost of Bernie shows the narrator a customer with a thumbprint. But the narrator doesn’t feel good about showing her his peen because she just so happens to have rocked up with his high school girlfriend. He hides in the staff kitchen for the rest of his shift. Besides, he’s too rattled to work.

Back at the apartment, the ghost of Aunt Bernie has been harassing the narrator’s sister, Min, to bake something. She needs to learn to cook. The sister is covered in flour. She and Bernie are in the same sort of slanging match Min and cousin Jade get into.

Bernie now has access to what’ll happen in future if her family don’t follow her advice. Min’s son Baby Troy will die a horrible death on such-and-such a date if she doesn’t get her act together.

The ghost body starts to disintegrate. Body parts fall off in a comically gruesome way. She asks for a washcloth. Time is running out. Everybody better start to hurry up and take her advice before she decomposes completely.

She instructs the narrator once again to “Show your c*ck” before dying again. The decomposing body disappears.

The story ends with the narrator having asked a colleague at the strip club how to make more money by showing his genitals. The plan is working, he’s making more money this way and also paying off Bernie’s headstone.

Aunt Bernie still comes to him occasionally in dreams. As an inversion of the Biblical messaging which reassures us that the dead appear to us as they did in life, Dead Aunt Bernie is a completely different character now she’s dead.

(Cf. Matthew 17:3–4, Luke 16:19–31, 1 Samuel 28:8–17, 2 Samuel 12:23.)

Yep. Sweet, hard-working and grateful in life, Aunt Bernie is debauched and annoyed in death. “Why did I get nothing?” she asks the narrator via dreams.

Each time, the narrator replies, “I don’t know.”

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “SEA OAK”

- Who are the central characters in “Sea Oak”? Can you think of similar archetypes from other stories?

- Describe the setting of “Sea Oak”. Can you think of real world locations which remind you of this one?

- How is “Joysticks” strip club both similar and different from other fictional depictions of strip clubs you can think of?

- How does Saunders write this story as satire rather than, say, gritty realism or horror?

- Can you think of other satirical stories with a similar tone? (On screen or on the page.)

- There’s nothing subtle about the character archetypes as depicted in “Sea Oak”. Do you consider satire a good choice for telling a story with themes of poverty and disenfranchisement? Why, or why not?

- At the end of the story, Saunders inverts (or at least plays with) a Biblical idea that our loved ones are recognisable in death. What other Biblical idea hasn’t worked out for Bernie? And what does this say about the American dream?

CAST OF CHARACTERS IN “SEA OAK”

JOYSTICKS CHARACTERS

The strip club is called “Joysticks”. There, women can pay male strippers to join them in model airplanes in role play scenarios as pilots etc.

- Mr Frendt is the narrator’s boss at the strip club. He fires men who are past their use-by date and getting frumpy.

- Thomas Kirster is “our beautiful boy” — bright blue eyes, muscular, popular with the patrons

- Lloyd Betts has put on weight, thinning hair, has a wife and two kids, lives in a duplex on Self-Storage Parkway, gets little stripping work and ends up playing Solitaire in the corner, gets fired for being past his use-by date

- Ed Anders is the man from the Board of Health who does visits to check the male strippers are not showing their pen!ses or kissing anyone, maintains a sense of humour about his job, reluctantly shuts the place down one afternoon while trying to enjoy his bar meal

- Sonny Vance is a stripper who shows his private parts to earn more money because he is saving up for a FaxIt franchise

- Mel Turner is another named character who is paid to oil-wrestle with the narrator

THE UNNAMED NARRATOR

- a stripper at “Joysticks”, male

- Bernie’s nephew

- lives in a subsidized apartment complex called ‘Sea Oak’, a dangerous neighbourhood

- Aunt Bernie, his sister, cousin and their babies live in the same apartment

JADE

- the narrator’s cousin

- the ghost of Aunt Bernie tells Jade to get a job

- has a baby (called Mac)

- studying for her GED

MIN

- the narrator’s sister

- the ghost of Aunt Bernie tells Min to babysit and how to cook so Jade can work outside the apartment.

- also has a baby (called Troy) — Troy’s walker gets hit by a stray bullet

- also studying for her GED

Like Statler and Waldorf on The Muppet Show, Min and Jade are depicted as different iterations of the same basic archetype. Both Jade and Min are written as high school dropouts who watch terrible talkshow TV which revels in violence. They don’t know a triangle has three sides, and regularly use language wrongly. In a more subtle depiction of their disenfranchisement, Saunders tells us they used to work the Info booth at HardwareNiche but the daycare lady didn’t work out. This speaks to the double bind experienced by single mothers. Sometimes it makes no good sense to work outside the home.

AUNT BERNIE

Aunt Bernie is introduced after all those other characters have been introduced, which lends the feel of a grand entrance.

- 60 years old

- unlucky her whole life but doggedly optimistic

- peacemaker of the family

- glasses, a perm, walks with a limp

- happy to have a roof over her head

- never married, no children, because the narrator’s grandfather required she stay home and look after him after grandmother died

- was screwed over in that regard because the grandfather left all his money to a woman none of them had ever heard of

- works at DrugTown for minimum wage, was demoted from cashier to greeter

- goes anywhere by bus

- only holiday she ever had was a gambling bus trip to a shopping mall in Quigley, Kansas (not a real place, from what I can see).

- dies of fright when an intruder breaks into the apartment

- comes back as a debauched p!ssed off ghost meting out life advice

THE NARRATOR AND MIN’S PARENTS

- the father died leaving no money to anybody

- the mother now lives with a man called Freddie and has minimal contact, we meet her at the funeral parlour

- we meet Freddie at the funeral, he gives a decent speech, smells of liquor, then takes the family to lunch at a Vietnamese restaurant

LOBTON

- owner operator of Lobton’s Funeral Parlor, a creepy place

- evinces the reality that even after death, in a capitalist economy Americans are used to make others money

- it will take seven years to pay off Bernie’s headstone and funeral expenses, and this is the cheapest Lobton can do without disrespecting her person

FATHER BRIAN

- takes care of the cemetery

- phones with news of Bernie’s disappearance

- he turns up with useless advice as to what to do about the ghost, probably all said with a smile

- Father Brian reminds me of Pastor Jeff on TV sit-com Young Sheldon.

ANGELA SILVERI

- used to date the narrator in high school

- shows up at the strip club

- Angela had dreams of escaping poverty and broke up with the narrator owing to his family situation

DEPICTIONS OF POVERTY IN FICTION

George Saunders chose satire for this story of American 1990s poverty. In the 2020s, there is an increasing pressure for writers to ‘stay in their lane’ when it comes to writing social class.

Leaving aside the biography of the author himself, let’s take a look at a film directed by Ken Loach: I, Daniel Blake (2016). Loach has been criticised for over-stating the plight of poor people when they try to access benefits in the UK.

If you haven’t seen this social realist film from England you may have seen the American Netflix TV series Maid. I, Daniel Blake is similar to Maid in its depiction of abject frustration and hopelessness in the face of bureaucracy. Whereas the main character of Maid is very palatable to wealthy audiences (for her beauty, her Good Mothering, even for the way she speaks), Daniel Blake is a straight-talking Northerner. However, Loach uses various storytelling techniques to ensure any audience will readily empathise with him.

Some critics have said that Ken Loach should stay in his lane and that his depiction of poverty is an exaggeration.

Not everyone agrees that I, Daniel Blake is hyperbolic in its depiction of British poverty, with its punitive and overly contemptuous bureaucrats, its impossible circle of paperwork. Viewers who have been through the system themselves will likely feel that, finally, their own lives are depicted on screen.

Leaving aside who is ‘allowed’ to write who in film and literature, it is common for privileged audiences to criticise a film-maker or author for ‘overdoing’ the experiences of marginalised characters and communities. This speaks to exactly why we need a diversity of experiences depicted in popular narrative.

There’s little nuance of poverty in I, Daniel Blake, and there is even less nuance here, in Saunders’ satirical short story about poverty and its dangers.

THE SATIRICAL TONE OF “SEA OAK”

What if “Sea Oak” had not been told as satire, but conveyed with a tone of gritty social realism instead?

Writing about the political issues in I, Daniel Blake in the Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, A. Wilde has this to say:

The telling of a more ‘nuanced’ story, open perhaps to alternative readings, would fail to do justice to the brutalism and Orwellian truths of the ways people experience the UK welfare system. … it is unlikely that many of those who are not reliant on benefits can begin to comprehend the extent and depth of the damage that recent policies, rules, and processes have on those who need assistance from the Department of Work and Pensions. And questions of ‘accuracy’ of this film have invariably been posed by those … who have little or no direct experience of the benefits system.

A. Wilde

What feels like ‘realism’ to a wealthy audience does not get to the reality of what it’s like to live in long-term economic distress, with bodily capital as your only capital, and the threat of death never far.

- White readers don’t necessarily ‘believe’ that racism is as bad as BAME writers say it is

- Cisgender readers don’t ‘believe’ just how dangerous it is to navigate the world while trans

- Men don’t ‘believe’ that sexual harassment/assault is as prevalent as woman writers say it is…

- and so on.

The novel Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang is all about this. A commercially unsuccessful white writer steals the manuscript of a commercially successful Asian author who dies in a freak accident. She then passes it off as her own after reading some non-fiction books on the dead writer’s culture. But first she edits out the parts which she considers hyperbolically racist.

When George Saunders made the decision to write satire when telling a tale of poverty, he skirts around the ‘believability’ issue. We aren’t supposed to interpret this story ‘as is’. But by going over the top with it, this removes the possibility for privileged readers to come up with other interpretations, filtered and watered-down through their own privileged lens.

The downside of defamiliarization via satire: Possible further Othering of the poor. However, readers must take some responsibility at some point, I feel.

Notice, too, how the author is sure to include numerous names of companies throughout the narrative. Business names from any other era always sound odd, collectively.

THE STRIP CLUB SETTING OF “SEA OAK”

George Saunders opens his short story with an evocative, concise description of a fictional strip club which employs men and caters to straight women.

Roughly 90% of all exotic dancers are female. Saunders has written the less common scenario — a gender inversion of the expected. Gender inversion is part of the satire. Further, by narrowing the theme of the club to airplanes and pilots, he sets up a slightly ridiculous tone which endures across the story and prepares readers for the supernatural twist.

Even within a supernatural story with this unexpected setting, Saunders is saying something important about real world issues:

- bodily capital

- the privilege of formal education

- gender

- socioeconomic injustice

- bodily safety

- the promise that if we work hard and stay meek we’ll be rewarded in the afterlife

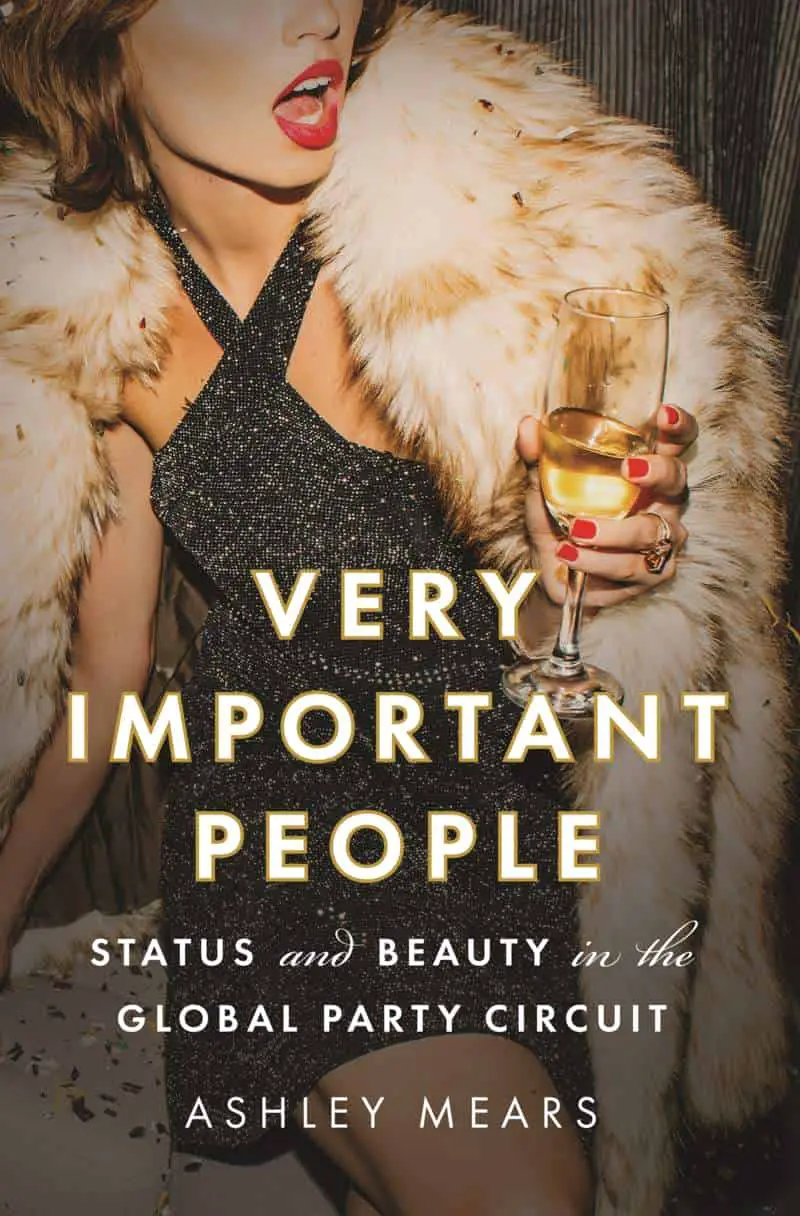

Let’s take a look at a few of these social issues via ‘The Global Party Circuit’ as described by sociologist Ashley Mears.

Very Important People: Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit by Ashley Mears

In Very Important People, sociologist, author, and former fashion model Ashley Mears takes readers inside the exclusive global nightclub and party circuit—from New York City and the Hamptons to Miami and Saint-Tropez—to reveal the intricate economy of beauty, status, and money that lies behind these spectacular

marketing copy

A sociologist and former fashion model takes readers inside the elite global party circuit of ‘models and bottles’ to reveal how beautiful young women are used to boost the status of men

Million-dollar birthday parties, megayachts on the French Riviera, and $40,000 bottles of champagne. In today’s New Gilded Age, the world’s moneyed classes have taken conspicuous consumption to new extremes. In Very Important People, sociologist, author, and former fashion model Ashley Mears takes readers inside the exclusive global nightclub and party circuit—from New York City and the Hamptons to Miami and Saint-Tropez — to reveal the intricate economy of beauty, status, and money that lies behind these spectacular displays of wealth and leisure.

Mears spent eighteen months in this world of ‘models and bottles’ to write this captivating, sometimes funny, sometimes heartbreaking narrative. She describes how clubs and restaurants pay promoters to recruit beautiful young women to their venues in order to attract men and get them to spend huge sums in the ritual of bottle service. These “girls” enhance the status of the men and enrich club owners, exchanging their bodily capital for as little as free drinks and a chance to party with men who are rich or aspire to be. Though they are priceless assets in the party circuit, these women are regarded as worthless as long-term relationship prospects, and their bodies are constantly assessed against men’s money.

A story of extreme gender inequality in a seductive world, Very Important People unveils troubling realities behind moneyed leisure in an age of record economic disparity.

extended marketing copy

Interview with the author at the New Books Network is here.

BODILY CAPITAL

The body acts as a resource and has a value in the way they look, especially for women. “Embodied cultural capital”. The easiest place to understand this is in the fashion modelling industry. The VIP night club industry is another example of where women’s bodies can have exorbitant value. Members will spend exorbitant amounts to spend time with women who look like fashion models. Women with this bodily capital attract men with economic capital, which is valuable to night clubs. The club will stack tables with models in all four corners of the venue to give anybody the impression, no matter which direction they look, that they are surrounded by women who are very young, tall, thin and mostly white.

This rare beauty has been sanctified by the modelling industry. They carry their status in their bodies.

To get these women (“VIP girls”) in the room, night clubs hire someone called a ‘party promoter’. Party promoters work on contracts. Their job is to get as many of these women to the club as possible and keep them there. Their pay depends on the ability to achieve this goal. A new party promoter might get $200. An experienced party promoter might receive up to $1000 per night.

GIRL CAPITAL

Ashley Mears refers to ‘bodily capital’ as ‘girl capital’ as it is very highly gendered. Although the place is full of women, there are no women in this space. They are all ‘girls’. Girl is a specific social category. By virtue of stepping foot in the space, a woman becomes a girl. She is not seen as fully socially competent or economically independent or fully mature. She’s definitely not a very serious person. Ashley was herself in her early thirties when she was going into clubs to do her research and found that, even after telling people her age, she was consistently referred to as a ‘girl’.

In fashion all the women are called girls, even though male fashion models are not called boys to the same extent. In many parts of the social world, women well over the age of 18 and established in their pursuits are commonly called girls. This term has seeped into popular usage, but the idea of the girl comes out of the 1800s, working class England. A girl was a young woman not yet married: frivolous, assumed to be mostly about consumption, isn’t taken in full seriousness. This was a modern identity to do something other than be in the home and take care of children, aligned with the domestic sphere. The idea of the young woman as a ‘girl’ gained popularity around the world.

Mears mentions the book which talks about the history of the adult girl: The Modern Girl Around The World: Consumption, Modernity and Globalization, Around the World Research Group, Duke University Press (2008).

During the 1920s and 1930s, in cities from Beijing to Bombay, Tokyo to Berlin, Johannesburg to New York, the Modern Girl made her sometimes flashy, always fashionable appearance in city streets and cafes, in films, advertisements, and illustrated magazines. Modern Girls wore sexy clothes and high heels; they applied lipstick and other cosmetics. Dressed in provocative attire and in hot pursuit of romantic love, Modern Girls appeared to disregard the prescribed roles of dutiful daughter, wife, and mother. Contemporaries debated whether the Modern Girl was looking for sexual, economic, or political emancipation, or whether she was little more than an image, a hollow product of the emerging global commodity culture.

Economic structures and cultural flows that shaped a particular form of modern femininity crossed national and imperial boundaries. Images and ideas of the Modern Girl were used to shore up or critique nationalist and imperial agendas.

There’s also this book with a focus on Canadian modern girls:

The Modern Girl: Feminine Modernities, the Body, and Commodities in the 1920s by Jane Nicholas, University of Toronto Press (2014).

With her short skirt, bobbed hair, and penchant for smoking, drinking, dancing, and jazz, the “Modern Girl” was a fixture of 1920s Canadian consumer culture. She appeared in art, film, fashion, and advertising, as well as on the streets of towns from coast to coast. In The Modern Girl, Jane Nicholas argues that this feminine image was central to the creation of what it meant to be modern and female in Canada.

Using a wide range of visual and textual evidence, Nicholas illuminates both the frequent public debates about female appearance and the realities of feminine self-presentation. She argues that women played an active and thoughtful role in their embrace of modern consumer culture, even when it was at the risk of serious social, economic, and cultural penalties. The first book to fully examine the “Modern Girl’s” place in Canadian culture, The Modern Girl will be essential reading for all those interested in the history of gender, sexuality, and the body in the modern world.

The Modern Girl description

VIP girls tend to be young women new to the fashion industry because most models don’t make much money. The labour market is very uneven (like writers and other artists). They tend to get a “free” dinner when they go to the night club. If they’re new to New York, they don’t have an existing social network, so this work soon tends to become very important to them in various ways.

Many American novels revolve around money, but the money’s already been made and the books are only about the adjacent symptoms bubbling up around money: the corseted manners of the wealthy and so on. Money has this almost transcendental place in American culture, yet it’s also taboo – we don’t talk about it and we don’t even understand it.

Hernan Diaz

A number of students also become VIP girls. Certain universities are known for having fashionable women.

Promoters will invite anyone to the table so long as she has the right look: Real estate agents, retail workers, women who work in finance and accounting. Some might even be doctors and other professionals who have a significant amount of education behind them. No matter what their background, they will be called “girls”.

The work involves providing an experience and this involves the girls giving emotional labour.

Why do people consent to their own exploitation? Why do workers work hard? If they’re compelled to work for a wage, why put in extra effort? We see this happening in many different industries: hard workers in bad conditions with poor pay. Fashion models are willing to accept getting paid in gifts of trade (clothing) or even nothing for the privilege of appearing in a high status magazine (for exposure). This is common in so-called culture industries.

Promoters in the VIP industry make a lot of money, perhaps $200k per annum in cash. The nightclubs are also very successful. Some are international chains. The people who run the nightclubs do very well and belong to the economic elite. But the Girls don’t get paid.

This world is run by men, for men, but on girls. The promoters and club owners all see Girls as valuable. They fully understand the concept of bodily capital.

SO WHY DO YOUNG WOMEN WANT TO BE VIP GIRLS?

Free meals, champagne, rides to and from the venues, perhaps extending to plane tickets out to Miami or to The Hamptons and other expensive places where wealthy people hang out.

Once Girls are at the table, managerial control is exerted to get the Girls to stay at the table for three hours while the promoters are working. (Generally midnight until 3am.) This is a long time to be in a club. Patrons don’t tend to stay in a club for that long. Promoters need to show management they had a full table all night long.

Discipline: This is a balancing act because while the promoter is recruiting and mobilising Girls as capital, the Girls aren’t supposed to feel like it’s work. She has to feel like she’s having fun, leisure not labour.

THE ROLE OF PROMOTERS

This requires a strong relationship between Girl and promoter, who needs to use his persuasive powers to get her to stay at the table. One of the promoters turned his back to a girl who wasn’t wearing what he expected at the club. There’s an implicit dress code. They need to dress in a sexy way including high heels. Some promoters keep a little black dress and high heels in their car and sometimes make Girls change or go home. When promoters bring Girls into the club, management and door people take notice. If the young women don’t fit the look, the promoter gets a financial hit, or lose his reputation. Other clubs might not want to work with him. Other Girls may not want to be around him.

Some promoters are women, though the vast majority are men. Out of 44 promoters, only 5 were women and they weren’t easy to find. It’s a man job counting sheer numbers but it’s also a man’s job in that heteronormativity are so engrained. One thing a promoter uses to get Girls to the table: flirtation. Innuendo etc. Promoters will also have sex with the Girls at times, and do look a lot like pimps in this respect.

There’s also a roughness that transpires between clubs and promoters. It’s highly competitive and requires assertiveness which looks at times more like aggression. Club management is of course also overwhelmingly male.

The five promoters who were women operated very differently. Realising they lacked the ability to flirt, they built friendships with the Girls. Female promoters have a harder time controlling the Girls, holding their interest at the club and dealing with club management.

The promoters and Girls both know they’re being used by the other.

Over time, Mears started to empathise with the promoters because she could see they were in a dominated economic position, but generally dreaming big. Although some of them are earning $200k per annum, this success feels inadequate when you’re comparing yourself to someone making millions. These men are perpetual dreamers. But also, they don’t see the way they’re treating women is exploitative. From their perspective, they think the arrangement is a mutual exchange. That’s not true for all of them; some of them are far more exploitative than others. Sociologists tend to think that if something is exploitative, it must also therefore be intolerable and experienced by people as unjust. It certainly can be, but it need not be.

HOW DO THE GIRLS FEEL ABOUT MAKING MONEY FOR OTHER PEOPLE?

In interviews, the Girls knew that promoters made money off them. They were generally surprised to learn promoters could make so much money but this didn’t awaken in them the feeling that this was unjust. They felt the exchange was fair. Promoters opened up a world of entertainment and leisure they otherwise had no access to. Some promoters help the Girls navigate this world carefully, keeping them away from predatory men and drugs. “Everybody’s using everybody.” The problems happen when the line is crossed to abuse. But just using someone is perfectly all right.

Promoters and models frequently referred to each other as friends. This was the same for the clients. The promoters introduced wealthy guys as friends. Promoters earn commission if the clients (“friends”) are buying bottles. The word obfuscates a disreputable exchange. It doesn’t sound good for a broker to bring girls to a client and get paid for it. This sounds close to sex work. It doesn’t sound good for a promoter to have all these unpaid young working women at his table and call them his unpaid employees, so “friends” is handy for discourse.

FRIENDSHIPS BETWEEN GIRLS AND PROMOTERS

However, real friendships do develop. Some Girls adore their promoters.

But aren’t friendships always transactional in some way? How many are pure and devoid of interest?

The promoter’s playbook:

- Meets a new young woman

- Offers her gifts and lunch, yoga classes

- Offers to drive her to her castings on a rainy day

- Come stay at my friends’ mansion at The Hamptons

TYPOLOGY OF GIRLS RECRUITED (OR NOT)

In George Saunders’ fictional strip club, the men are sorted into groups by the customers:

- Knockout (Thomas Kirster)

- Honeypie

- Adequate

- Stinker (Lloyd Betts)

Here’s how young women are categorised in the 2020s VIP party circuit by the customers:

GOOD GIRL

The Good Girl doesn’t come out very often but she’s the sort of girl clients would seek for a long term relationship.

PARTY GIRL

This type of Girl stands in opposition to The Good Girl. All promoters want this girl. She looks like a model, parties hard, enjoys the scene and reliably comes out night after night. If a Girl is going out on the regular with a promoter she doesn’t need to wake up early the following morning, so probably doesn’t have a regular, full-time job.

However, these Girls are without value when it comes to a long term relationship.

PAID GIRL

A number of women occupy this category in a club:

- sex workers

- cocktail waitresses (“bottle girls”)

- table girls (hired by the club to stand at the bar — joins clients who request her company, like an Asian “hostess”)

There are varying degrees of commodification of sex. The table/bottle girls are generally considered sex workers, even though they’re being paid for displaying their beauty and providing company.

AGEING OUT OF THE PARTY CIRCUIT

Like athletes, and like Lloyd Betts in Saunders’ short story “Sea Oak”, VIP Girls soon age out of their jobs. Nor can promoters do that job forever.

A promoter might be a woman in her 30s who had formerly been a Girl at the promoter’s table. She returns once or twice. This is considered okay so long as she has her heels on. Generally, the young women move on without being pushed. Unlike the fired man of George Saunders’ short story, the women know their own expiry date. Also, they don’t tend to be interested in this work past their youth. They get partners, perhaps children.

The advancing age of promoters is problematic for different reasons. It can look unseemly for a 45-year-old man to be chasing 18-year-olds to join his table. That said, some male promoters are in their 40s. Those in their 20s look at these guys as both legendary successes but also see them as failures due to their ageing bodies.

MEN’S DISPROPORTIONATE CAPACITY TO PROFIT FROM WOMEN’S BODILY CAPITAL

Sex work, stripping, bar work — these are obvious ways in which we see men profiting from the bodily capital of women. For this reason, George Saunders’ story would not have worked so well as satire had the gender of the narrator been flipped; it would have felt too close to the bone.

Mears sees men profiting from women’s bodily capital beyond the most obvious realm of the entertainment industry. Even among her own sociology students, a number of the freshmen start partying in Greek life (the fraternity system). This entire system is geared around garnering as many young women into parties as possible. (Women don’t have to pay to get in, for instance, whereas the men do.)

Cheerleading is another interesting example. Cheerleaders put a huge amount of effort into promoting a team but aren’t able to make much money. They are paid in status e.g. given game tickets.

Beyond that, women’s bodily capital is used to sell all kinds of things in which disproportionate profits go to men. Think of good-looking young women working in retail, hotels and tourism, or the display of women in various frontstage positions: hostesses, on shop floors.

Takeaway idea: Exploitation and pleasure often work together.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Related to the night club girls:

Money Diaries launched in January of 2016, premised on the idea that “the first step to getting your financial life in order is tracking what you spend.” By encouraging young women to record their expenditures, and to discuss their finances frankly, Refinery29 could, the theory goes, help young women become savvier about money. The first woman to brave the experiment was a twenty-seven-year-old Brooklynite making sixty-five thousand dollars a year in an undisclosed “creative industry.” Her entry was candid and funny: she ordered buffalo wings and a large pizza for herself late at night ($28.74); bought beauty products online, to compensate for being unhappy at work ($59); ordered a copy of a novel on Amazon ($10.66); and dabbled in cocaine (gratis). “I don’t know how much drugs are supposed to cost, but I heard coke is pricey,” she wrote. “I just did a line because it was offered, and I was drunk. The alcohol was free, too.”

In the world of the Money Diaries, she quickly learned, no amount of honesty goes unpunished.

Money Diaries, Where Millennial Women Go to Judge One Another’s Spending Habits

A critique of “Sea Oak” at “Why Is This Good” podcast:

In this episode, we discuss “Sea Oak” by George Saunders. What can we learn from this crazy, hilarious story? How can fiction bring internal conflict into concrete reality? How can we create a concrete representation of a character’s self-reflective feelings? How can we create a satirical tone that is true to character? How do we imagine characters that are different than we are? How as writers can we do weird, memorable stuff and have fun?

Why Is This Good? podcast