SCHOOL AS THE WILD WEST

School itself must be so different these days than it was when you were in school. Certainly, having kids helps, but is that ever an issue for you when you’re writing?

I was reading about this phenomenon in television and film writing, which is that the references to school are always at least 20 to 30 years old, because writers are really writing about their own experiences, so these movies are hopelessly outdated. What I’ve been surprised with is that school seems a lot safer and more benign than it was when I was in junior high. You know, for me, junior high was like the Wild West. There must have been one teacher for 35 kids, and we were completely unprotected from the bullies, so the experiences I’m writing about in my book are actually very watered-down from real life experiences.

Jeff Kinney at Mental Floss

HIGH SCHOOL AS LABYRINTHINE HELLMOUTH

If one is going to construct a Hellmouth, a convergence of beasts, evil, and demons, a high school may be the only logical site. Despite the rose-tinted glasses with which adults tend to view their secondary school years, high school for most teenagers can be a place teeming with horror — a labyrinth of biased and outdated curriculum to negotiate made all the more impossible by the constant barrage of socialization terrors that push one into adulthood. And yet, for a variety of reasons, teachers continue to lack the understanding required to share in the teenage discourse and thus truly connect with their students, and without connection, it seems unlikely that legitimate security can be achieved.

Jennifer Job

HIGH SCHOOL AS HORROR ARENA

[T]he school setting is not incidental to teenage horror. Rather, school is so integral to the fears on which these stories play that its significance goes unnoticed. Schooling constructs much of young people’s social and cultural environment and is intimately connected with many of their fears and anxieties. Schools set the criteria for success and failure, socially as well as academically, and create a world in which individuals are accepted or rejected on an almost daily basis. Part of the horror in the horror genre is based on exaggerated versions of these fears. Conversely, though, in horror, school is also the place where the control that schools should exert breaks down. Schools are orderly places, governed by timetables, bells, regulations, curricula, examinations and right and wrong answers that help to control the dangerous, surging, chaotic energies of adolescence so that young people can pass safely into well-regulated adulthood. The ‘Horror School’ is the realization of the teenager’s fear that these desires may take over, that their inner turmoil will take control.

Christine Jarvis, School is hell: Gendered fears in teenage horror, Educational Studies 2001

My own high school English teacher hated Dead Poet’s Society. He never said why, and we never asked. Then I became an English teacher myself. Then the #metoo movement happened, and I really hated it then.

Stories set in schools haven’t been the same for me since my teachers’ college year. Dead Poet’s Society ceased to be a story about an inspirational, enthusiastic English teacher and more a demonstration of an egotistical lover of attention who would have served his students better if he had tried a bit of group work. (Jumping around on desks is also considered uncouth in a country where even sitting on desks is a no-no. This was New Zealand.)

As and aside, Dead Poet’s Society hasn’t aged well, either. There is a sexual assault scene which is not treated as such. For more on that I’d recommend listening to this episode of the Story Grid Podcast rather than watching the entire movie again.

Dead Poet’s Society is just one example of an unrealistic, annoying but romantically idealised teacher. While teaching high school myself, I had zero patience for stories in which fictional teachers keep individual students behind after class to speak to them about various misdemeanours — mostly, these teachers were young men in fake horn-rims who, had they been of truly innocent intent, as we were meant to believe as the audience, would have made sure never, ever to be in a room alone with any student. Don’t keep students behind after class. If you do, keep them back in a small group. Keep the door open. Teaching 101.

Dead Poet’s Society is a more contemporary teenage take on the Roman Carpe Diem body of narrative, united by the common theme that we must live in the moment and make the most of whatever comes our way. Older examples largely come form poetry: “To His Coy Mistress,” (Marvell), “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time” (Herrick).

It was the large classes of eerily silent student, in which the actor posing as teacher makes zero use of body language, has no slightly embarrassing strategies for gaining everyone’s attention.

In fictional classrooms, the teacher walks around the classroom and everyone watches in rapt attention, even though the students at the front of the classroom can no longer see, nor hear. The teacher with magical magnetism approaches a single student’s desk to engage more closely with them when, in reality, as soon as the teacher moves from the front of the room, the class is likely to break out into little groups chattering. “Don’t do what actors always do on TV,” our teachers’ college lecturer warned us. “Stay at the front of the classroom until you’ve finished talking to the entire class.” The ‘rules’ of body language, standing position and classroom management are not something that has been picked up by film-makers, who are in love with the ‘camera moves around the classroom’ technique.

Also: “Don’t confiscate passed notes and read them aloud to the class. Crumple them up and throw them into the bin without looking at them” Anything else is a shaming technique, which went out of vogue decades back.

In sum, teachers’ college is a year in which naiive student-teachers’ hopes and dreams about what the Role of Teacher might be like are moulded into something more closely aligned to reality. Still, it amazes me how, even though all of us have known a lot of teachers over our 13-odd years of schooling, we nevertheless accept quite a chasm between the reality of teaching and the fictional portrayals. We accept these fictional teachers partly because narrative has its own rules; likewise, police officers are not usually damaged alcoholics who can’t maintain a healthy family life and eat nothing but donuts, but we see this character all the time in the crime genre.

On movies, the bell rings and everyone gets up to leave. No fictional teacher says, ever, what I said weekly: “The bell is a signal for me, not for you.”

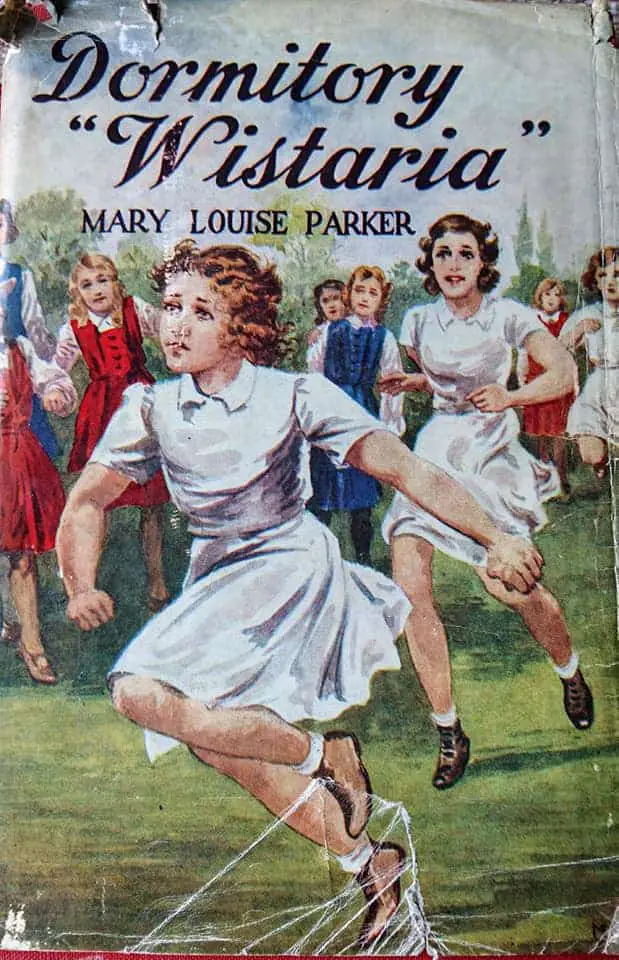

IDEOLOGY OF SCHOOL STORIES FOR BOYS AND GIRLS

Beverly Lyon Clark defines a specific subset of adolescent literature, the traditional school story, as a story set at a school, that is addressed to children from the point of view of a child. The text is usually middle-class in its perspective. If the canonical boys’ version of these books can be said to have a formula, it is this: they cover a broad range of years, from an ordinary boy’s arrival at the school, through his years of service to older boys until he is himself one of the older boys at the school. Two types of adventures occur: competition at physical activities, such as sports, and some sort of social conflict that allows the text to explore morality. The tale may conclude with an affirmation of the school’s purpose in training young people to take their place in the status quo of the social order. Certainly girls’ school stories serve the same ideological purpose, which is the most important purpose of School Stories; their agenda to indoctrinate children into the social order is thinly veiled.

[…]

Since American YA novels are usually Entwicklungsroman, they are far more likely to focus on one set of problems than they are to show a character developing over a period of time as School Stories generally do. But although the time line of the plot may be telescoped, the function of the narrative remains the same: school serves as an institutional setting in which the protagonist can learn to accept her or his role as a member of other institutions.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

ON BOARDING SCHOOL STORIES IN PARTICULAR

Below, Spufford doesn’t mention the critic who said it, but this is the strongest argument I’ve seen for School Stories as antidote to indoctrination into the social order:

Children’s books can find a town in a boarding school if the author doesn’t play school life entirely for laughs, as in Billy Bunter, or Molesworth, or the Jennings stories. From Angela Brazil and the Chalet School books, through to the unexpected rebirth of the genre at Hogwarts in the Harry Potter series — where a new atmosphere, both magical and democratic, still does not displace such key features as a the sneering rich boy, and the contest for the house cup — school stories explore what are essentially autonomous towns of children. As a perceptive critic of Harry Potter pointed out, what makes the school setting liberating is that school rules are always arbitrary rules, externally imposed. You can break them, when you get into scrapes, without feeling any guilt, or without it affecting the loyalty to the institution that even unruly characters feel, right down from Angela Brazil to Joanne Rowling, Harry loves Hogwarts. The rules of conduct that really count are worked out by the children themselves, and exist inside the school rules like a live body inside a suit of armour. School stories are about children judging each other, deciding about each other, getting along with each other. The adults whose decisions would be emotionally decisive — parents — are deliberately absent.

Francis Spufford, The Child That Books Built

To write a book about a school for wizards which assumes the cruelty of the world is an unchangeable part of it, and anyways being cruel isn’t bad, is to fucking fail at at the whole premise.

@RadFemme74, 8:50 AM · Aug 1, 2021

According to John Rowe Townsend in Written for Children, ‘the school story sprang into prominence with the publication in 1857 and 1858 of Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s Schooldays and F.W. Farrar‘s Eric, or Little By Little.’ Before that, there were a few scattered books with schools in them, but these weren’t ‘school stories’ per se.

Tom Brown’s School Days is an episodic story with no tightly-knit plot. We see Tom first at home then as he starts life at Rugby, initiated into football, bullied, bearing it bravely, getting into scrapes and eventually looks after a timid new boy called Arthur. Tom grows a sense of responsibility and becomes a man.

Eric: Or, Little By Little concerns the fate of an individual with school in the background. Team spirit is of no great importance. The author became a headmaster and was a very popular preacher and writer. This was written while he was still in his 20s. It’s all about how Eric is constantly fighting temptation and evil. ‘Little by little’ describes the progress of his decline.

School stories were very popular in England in the Victorian era, though not so much elsewhere.

See: 11 Famous British Schools In Fiction

School stories seemed to make a bit of a comeback in the mid-1960s with the choir-school stories by William Mayne and novels by Antonia Forest and Mary K. Harris but the revival didn’t continue. (Mayne’s books were largely deliberately removed from shelves from 2004 onwards following his conviction and prison sentence for indecent assault on children.)

The originality of Mayne’s writing and his talents for telling original stories, often based on the search for something hidden or elusive, were obvious from A Swarm in May (1955), the first and most outstanding of his quartet of choir-school stories evocatively illustrated by C Walter Hodges. Swiftly followed by Choristers’ Cake (1956), it weaves the revival of an old tradition into a contemporary school story, showing how the past can influence and give strength in the present.

The Guardian Obituary

There are of course some very popular modern children’s books set in boarding school (e.g. Hogwarts) but the nature of them has changed. There was an aura of privilege based on class and money in the classical, high-Victorian and post-Victorian boarding school story and this hasn’t continued to the same extent.

Mildred Hubble is a trainee witch at Miss Cackle’s Academy, and she’s making an awful mess of it. She’s always getting her spells wrong and she can’t even ride a broomstick without crashing it. Will she ever make a real witch?

Most modern books for children are set in a day school rather than in a boarding school. Going to school is now a part of everyday life and school stories do not form their own genre.

THE OLDER TYPE OF BOARDING SCHOOL STORIES

A boarding school is a self-contained world in which children are full citizens.

The advantage of a boarding school setting is that the children are no longer subordinate members of the family. In some more recent stories, the students are absurdly powerful, and the teachers hardly get a mention at all, even though we’re to believe they’re there.

- At boarding school, personal politics are always in full swing.

- In school there is a natural opposition between what the children are supposed to do and what they will do if they get the chance.

- Familiar problems include: bullying, sneaking, initiation rituals, rule-breaking, and general conflict that comes about with shifting loyalties within the group.

- Participation in team sports is the ultimate character builder.

- A lot of these stories had heavily Christian/didactic messages.

It’s all Samantha needs to get her going again. Suddenly things are happening. She writes a play, The Old Haunted House, and her teachers are so impressed that they persuade Mr Shaw to put it on for the parents at the end of term. It’s Samatha’s chance to do something for Pine Street and to prove her worth to Mr Duncan and the others. Everyone gets to work and Pine Street becomes fun again. Then things start to go wrong. Is the play jinxed, or is someone out to wreck things for Samamtha? She and Jon Crewe decide to investigate…

An American classic and great bestseller for over thirty years, A Separate Peace is timeless in its description of adolescence during a period when the entire country was losing its innocence to the second world war.

Set at a boys boarding school in New England during the early years of World War II, A Separate Peace is a harrowing and luminous parable of the dark side of adolescence. Gene is a lonely, introverted intellectual. Phineas is a handsome, taunting, daredevil athlete. What happens between the two friends one summer, like the war itself, banishes the innocence of these boys and their world.

In this stunning and heartrending tale set in a Swaziland boarding school, two girls of different castes bond over a shared copy of Jane Eyre.

Adele Joubert loves being one of the popular girls at Keziah Christian Academy. She knows the upcoming semester at school is going to be great with her best friend Delia at her side. Then Delia dumps her for a new girl with more money, and Adele is forced to share a room with Lottie, the school pariah, who doesn’t pray and defies teachers’ orders.

But as they share a copy of Jane Eyre, Lottie’s gruff exterior and honesty grow on Adele, and Lottie learns to be a little sweeter. Together, they take on bullies and protect each other from the vindictive and prejudiced teachers. Then a boy goes missing on campus and Adele and Lottie must rely on each other to solve the mystery and maybe learn the true meaning of friendship.

Following the death of her closest friend in summer 1968, Meryl Lee Kowalski goes off to St. Elene’s Preparatory Academy for Girls, where she struggles to navigate the venerable boarding school’s traditions and a social structure heavily weighted toward students from wealthy backgrounds. In a parallel story, Matt Coffin has wound up on the Maine coast near St. Elene’s with a pillowcase full of money lifted from the leader of a criminal gang, fearing the gang’s relentless, destructive pursuit. Both young people gradually dispel their loneliness, finding a way to be hopeful and also finding each other.

FURTHER READING

Emmy’s dad disappeared years ago, and with her mother too busy to parent, she’s shipped off to Wellsworth, a prestigious boarding school in England. But right before she leaves, a mysterious box arrives full of medallions and a note reading: These belonged to your father.

Just as she’s settling into life at Wellsworth, Emmy begins to find the strange symbols from the medallions etched into the walls and stumbles upon the school’s super-secret society, The Order of Black Hollow Lane. As Emmy and her friends delve deeper into the mysteries of The Order, she can’t help but wonder—did this secret society have something to do with her dad’s disappearance?

The boarding school stories I grew up with starred white kids from well-off families who had been sent there by the families. Many children from native families have been required to attend boarding schools. See this article about boarding schools for native American children.

FURTHER READING

Representing Education In Film: How Hollywood Portrays Educational Thought, Settings and Issues

David Resnick combines two of his passions, movies and education, in his book, Representing Education In Film: How Hollywood Portrays Educational Thought, Settings and Issues (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). Films are powerful messengers which both project and reflect particular values, ideas and social behavior. Using many examples of Hollywood movies, Resnick analyzes the way movies perform in a variety of formal and informal educational settings, including sports, arts and religion. In this lively and engaging interview David Resnick shares insights he gained through decades of experience in education and research.

New Books Network

Living on Campus: An Architectural History of the American Dormitory

Every fall on move-in day, parents tearfully bid farewell to their beloved sons and daughters at college dormitories: it is an age-old ritual. The residence hall has come to mark the threshold between childhood and adulthood, housing young people during a transformational time in their lives. Whether a Gothic stone pile, a quaint Colonial box, or a concrete slab, the dormitory is decidedly unhomelike, yet it takes center stage in the dramatic arc of many American families. This richly illustrated book examines the architecture of dormitories in the United States from the eighteenth century to 1968, asking fundamental questions: Why have American educators believed for so long that housing students is essential to educating them? And how has architecture validated that idea? Living on Campus: An Architectural History of the American Dormitory (University of Minnesota Press, 2019) is the first architectural history of this critical building type.

Grounded in extensive archival research, Carla Yanni’s study highlights the opinions of architects, professors, and deans, and also includes the voices of students. For centuries, academic leaders in the United States asserted that on-campus living enhanced the moral character of youth; that somewhat dubious claim nonetheless influenced the design and planning of these ubiquitous yet often overlooked campus buildings. Through nuanced architectural analysis and detailed social history, Yanni offers unexpected glimpses into the past: double-loaded corridors (which made surveillance easy but echoed with noise), staircase plans (which prevented roughhousing but offered no communal space), lavish lounges in women’s halls (intended to civilize male visitors), specially designed upholstered benches for courting couples, mixed-gender saunas for students in the radical 1960s, and lazy rivers for the twenty-first century’s stressed-out undergraduates.

Against the backdrop of sweeping societal changes, communal living endured because it bolstered networking, if not studying. Housing policies often enabled discrimination according to class, race, and gender, despite the fact that deans envisioned the residence hall as a democratic alternative to the elitist fraternity. Yanni focuses on the dormitory as a place of exclusion as much as a site of fellowship, and considers the uncertain future of residence halls in the age of distance learning.

interview at New Books Network

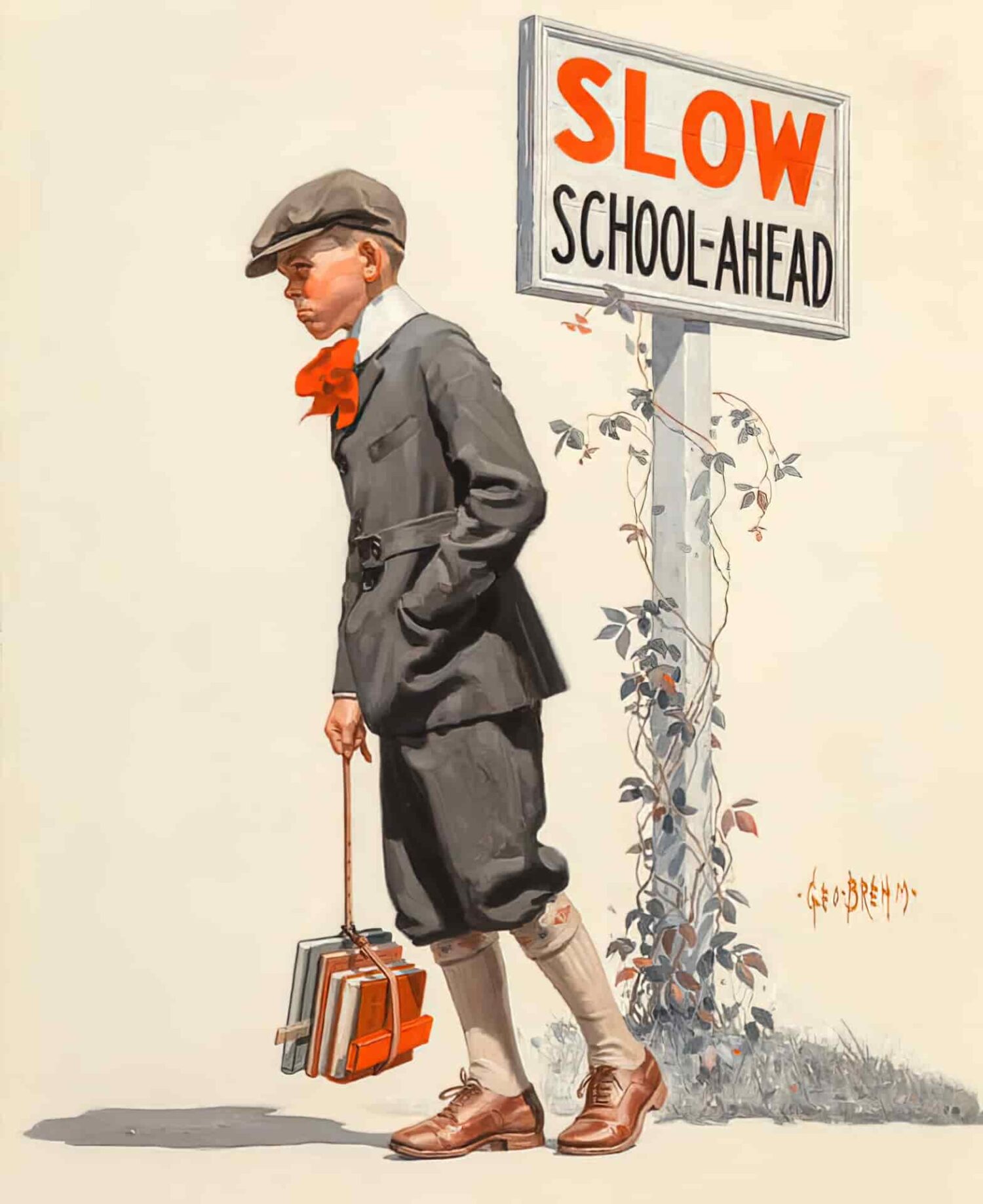

Header painting: Albert Ludovici – Kept In 1887