Schnitzel von Krumm’s Basketwork is a children’s picture book by New Zealand author-illustrator Lynley Dodd, first published in 1994. The star and only character of this one is… Schnitzel von Krumm… already familiar from the uber-successful Hairy Maclary from Donaldson’s Dairy.

Schnitzel von Krumm of course puts the reader in mind of crumbed schnitzel, a New Zealand pub standard.

Speaking of which, as an adult I no longer live in New Zealand. For some reason I moved to Australia. I thought my Australian-born husband was pulling my leg when he told me I could go into an Australian pub or a Leagues Club and order a ‘schnitty’. I’d never noticed that Australians shorten schnitzel to ‘schnitty’, even though I shouldn’t be surprised. They shorten everything else. I told him there’s no way I’m ordering a ‘schnitty’ for him to sit back and laugh. It can’t be a word. It’s too ridiculous.

But since he told me that, I’ve noticed Australians saying ‘schnitty’ all the damn time. Guess I heard it before, too, and had no idea what the hell everyone was talking about. I had to apologise with my tail between my legs for assuming a fair dinkum Aussie was having a lend.

Schnitzel von Krumm is an apt name for this dog, not least because he is so close to the ground and therefore pretty much flat. The Internet confirms that the character Schnitzel von Krumm is a red standard smooth-haired Dachshund. So let’s go with that.

PAGE LAYOUT

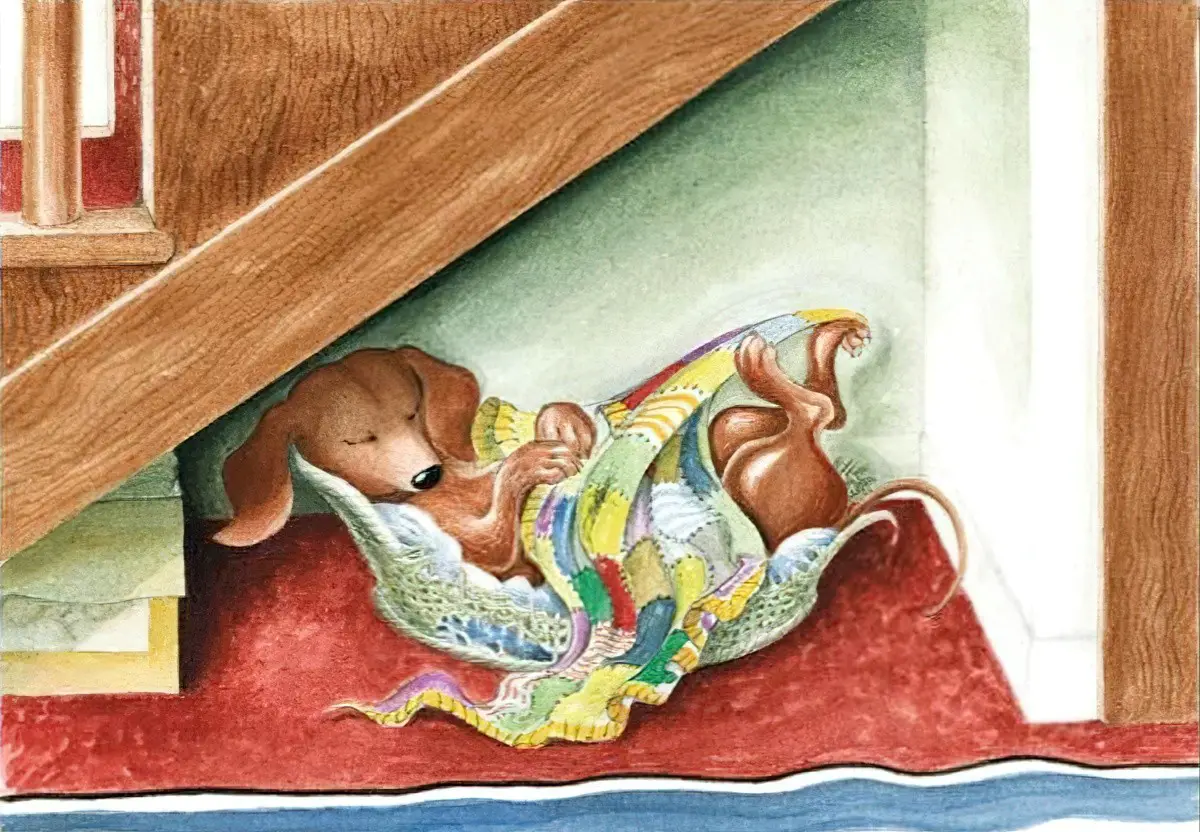

An interesting thing about the illustrations in this book: The cover, the first page and the second page are all pretty much the same image: Schnitzel von Krumm fast asleep on his back in his comfy basket. Once we’ve seen the stairs, the camera zooms in and now we are at ground level alongside Schnitzel, watching him as he sleeps. There are plenty of repeating images in this picture book, but Lynley Dodd will eventually increase the drama with a magnificent low angle shot.

RELEVANCE TO PRESCHOOLERS

Kids don’t always like change. They especially don’t like change if their favourite toy or blanket is taken away. These items tend to be removed only after they’re basically falling apart. The child still sees the original item, of course. These items exist mainly in the child’s imagination.

How does Lynley Dodd show us that the old basket is better than the new one? A well-used item is a beloved one. This basket is nothing if not well-used.

Also, the blanket is bright and colourful. It’s a patchwork blanket, suggesting someone took a long time to make it for him. This basket (and blanket) indicate love and care and attention. When his basket is displaced from under the stairs, it feels to Schnitzel von Krumm like HE himself has been displaced. No one likes his smell? A dog’s smell is him!

Young readers will understand this, too, especially if a sibling comes along after them. Why is the new so-and-so using MY cot and MY high-chair and MY sippy cup? Why do I have to sleep in the big bed?

WORD CHOICE, PACING AND RHYME

When read with New Zealand intonation and emphasis, Lynley Dodd’s rhyming schemes are a masterclass. (I understand not all English speakers thinks so. YA READIN IT WRONG!)

Let’s take a look at the first page.

Don’t let anyone tell you not to use semi-colons in a picture book:

Tucked in a hideyhole under a stair, lay a rickety basket in need of repair;

Now take a look at how Lynley Dodd uses capitalisation followed by three dots to slow the reader right down:

a chewed-up old cushion,

a blanket all worn,

everything broken

and smelly

and torn.

AND ...

The first page ‘zooms in’ to the image using words.

under his blanket,

his paws on his tum,

happily snoring,

lay Schnitzel von Krumm.

Turn the page and find the illustration is also a zoom-in. In this way, image marries beautifully with text.

ANTHROPOMORPHISM

Also, isn’t he just so cute? I love it when dogs lie on their backs snoring with their ‘arms’ in the air (because how can you not call them arms?) Lynley Dodd’s pets are very animal-like, but she does anthropomorphise to a certain extent, to the extent we pet owners are inclined to do to our own pets.

See also: Why So Many Animals In Picture Books?

AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION

The Hairy Maclary books are designed for read alouds, by adults to preschoolers. Many New Zealand kids know these picture books by heart by the time they start school. Lynley Dodd encourages this memorisation in a number of ways. One way: encouragement of reader participation.

As in a song, she sets up the refrain, then expects readers to know what’s coming.

Refrain: a regularly recurring phrase or verse especially at the end of each stanza or division of a poem or song : chorus also : the musical setting of a refrain. 2 : a comment or statement that is often repeated.

The refrain:

Did he mind?

Not a bit.

This is set up on page two. After that it happens on every second page, right after a question marking the pageturn, except it’s a little bit changed:

NO.

not a bit.

The final page goes back to ‘Did he mind?’, which means the book is (literally) bookended by the first version. It works very well. (P.S. capitalisation of NO encourages preschoolers to shout.)

STORY STRUCTURE OF BASKETWORK

As in many good melodramas, a character is enjoying their comfortable life at home when there’s an invasion of some kind. Something changes. The character must adapt. In picture books, it’s often low stakes (to adults) and in this case a dog has had his basket thieved. Like Schnitzel, readers never actually see who takes the basket. Adults deduce. We know it was the responsible adults of the house who took it away, and we understand the reasons (main one being it fair reeks). It’s easy to forget that, like Schnitzel himself, the youngest readers won’t know who took the basket. To them, the story will be scarier. SOMETHING HAS ENTERED THE HOUSE. WHO. A THIEF. This turns Basketwork into a Cosy Home Intruder story, at least in tone.

How does the plot build to a climax? Schnitzel von Krumm adapts to his changed situation by finding new places to sleep. There is much humour in his choices. The choices get more and more ridiculous, which makes this a carnivalesque story.

Lynley Dodd’s first published book was My Cat Likes To Sleep In Boxes (which is old enough for me to have grown up alongside with myself). You can probably guess what that one’s about from the title.

Despite what picturebooks normally try and teach kids, there is much crossover between dogs and cats, especially when we allow dogs inside our houses. Dogs aren’t quite as obsessed with receptacles as sleeping-containers, perhaps, but our pup does love to slide himself under the (low to the ground) couch and go apeshit, pretending the couch is his enemy pinning him down (ONE ASSUMES). Dogs, like cats, are very very good at finding the warmest, most comfortable bed. (Or in summer, the coolest spot. For your information: The tiles right outside the toilet.)

Would this story work with a cat as main character? PROBABLY. Except for one thing (in my experience): Cats aren’t quite so attached to their things. They are happy to sleep in the comfiest place, and are attached to their own, designated beds only when it remains the most comfortable place. Cats do not show as much object loyalty, though I am prepared to have my mind changed by anyone who’s cat experience is different.

Note that Schnitzel looks straight at the ‘camera’ when he’s getting into his new bed. That look on his face! NOT IMPRESSED.

Can dogs roll their eyes? He’s rolling. Note that this new bed has been placed in his hidey-hole with tender loving care. Someone has embroidered his initials onto the cushion. There’s an embroidered crown! Someone loves this dog. He’s their little prince.

Next, Schnitzel looks at the camera from under the pile of washing. This page functions a little like a Where’s Wally book, because he’s not immediately obvious. The dog is clearly trying to hide, and the youngest readers will feel smart for pointing him out. (If this were our ratbag puppy, he’d be chewing the washing up.)

Next he tries a cardboard box in the utility cupboard, which cannot be comfortable because it is full of preserving-jar tops. This is a wonderfully specific item and is also very cottage-core.

By the way, I’m yet to encounter a ‘messy’ cupboard in a picture book which comes anywhere near the level of what actually goes into a messy cupboard. For one thing, I find Lego everywhere. There aren’t nearly enough building bricks scattered around the child-inhabited homes of picture books. THERE IS DEFINITELY AT LEAST ONE LEGO AT THE BOTTOM OF THAT BOX. (Hidden, of course, because cottage-core does not accommodate for the likes of Lego.)

When someone comes to retrieve the vacuum cleaner, Schnitzel’s box tips over. But instead of running off, he stays inside the box, still trying to hide. He knows he’s not meant to be there. So cute.

Also, the vacuum cleaner is scary. Its arm (hose) reaches out in front of Schnitzel. He thinks it’s coming to suck him up, I bet. The hose has been detached while in storage, and there’s something about that hole which induces trypophobia. We can see right into the belly of the ogre. (Actually we can’t, but we can imagine.) Also, worse luck, if Schnitzel already has a fear of holes, he’s inside a box full of them. For what is a preserving jar screwy wotsit if not a hole? (That box is all screwies, no actual lids — typical. TYPICAL.)

Next Schnitzel tries to sleep in the vegetable rack on top of beans. We don’t know where in the house this is because it’s a close up. I’m guessing the pantry. Note his eyes. He’s no longer looking at the reader but towards the right. By now, Lynley Dodd has trained us to expect disturbance (by making use of the Rule of Three). Like characters walking through a book from left to right (in a Western-style book), Schnitzel’s eyeballs achieve the same effect.

Schnitzel is disturbed by someone throwing in a bag of carrots. Note that Lynley Dodd has chosen an orange vegetable to stand out against all those greens. (This is one healthy household. Also, those beans are going to taste like dog.)

Next, Schnitzel finds a bed outside, hidden by a bush (except to the viewer). The Chekhov’s Gun of this page is the sprinkler. This sprinkler makes the picture book a specifically New Zealand one, or perhaps a specifically 1980s one: When I was growing up, the suburban expectation was that everyone keeps their lawns green. If you do that today, in Australia, you’ll be ostracised for wasting water. People who water their lawns with grey water put up a sign to tell nosy parkers that’s what they’ve done. This water sprinkler sure is nostalgic.

Note that when Schnitzel runs away from the sprinkler, he’s running backwards through the book. His eyes look forwards, but with caution. Lynley Dodd depicts him running backwards because he wants to rewind time. He wants his old bed back, dammit!

Now we see him sitting wet and alone at the bottom of the stairs. The low angle view diminishes him. He really is a pathetic figure. All is hopeless. (Children sitting on stairs is a bit of a trope in storytelling.) The stairwell is the centre of the picture book dream house, and things can be overheard there. If a child ever wants to keep an eye on proceedings, they’d be well advised to take a seat on a stair.

Unlike the young readers, who will never get their cot back, doomed forever to progress through bigger sizes of everything until they are fully grown (and when does that happen, actually?), Schnitzel gets his bed bad. From his place on the stairs, Schnitzel von Krumm must see someone return his basket to its rightful place, in his hidey-hole. (The replacement of the basket is left off the page.) We see him get back into it.

Precisely because the wickerwork has been chewed (by himself as a teething puppy, I bet) it is the perfect height for him to step into with those stumpy little legs.

The outro image shows Schnitzel lying on his back, belly exposed. In all his other ‘beds’, he’s been curled up. This pose indicates he no longer feels vulnerable and can fully relax.

Dogs can’t smile. The best illustrators can do is let their mouths hang open. (The creators of the Muppets realised early in the piece that the muppets came alive as soon as they opened their mouths — like dogs.)

But if Schnitzel’s eyes aren’t smiling, I don’t know what is.