What can I say about “The Scarlet Ibis” that isn’t on Wikipedia? This 1960 short story is loved by English teachers because of its clear literary symbols — a good introduction to symbolism, especially to colour symbolism.

COLOUR SYMBOLISM

Students can be highly suspicious of close reading when teachers talk about colours and their symbolism. Colours can have multiple readings e.g. red can mean heat and anger but also love. So what’s the point, right?

Let’s take one step back. What even is a symbol? As shown by the ‘blue curtains’ meme in that post, sometimes a colour is simply an off-duty detail.

But the colour symbolism in “The Scarlet Ibis” is very much ‘on-duty’.

There is a good, watertight reason why Hurst’s older, wiser narrator sits in a green parlour, and here’s why.

Take the distinction between the youthful main character and his wiser, older narrator self, who I consider two separate characters (despite being simply the younger and older versions of the same person).

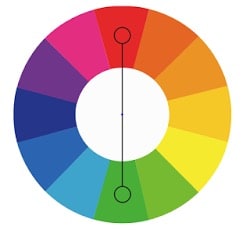

The older narrator barely resembles his younger self. This distinction — and his flipped sense of old man morality — is conveyed nicely in the opening paragraph via the complementary colours of red and green.

Summer was dead, but autumn had not yet been born when the ibis came to the bleeding tree. It’s strange that all this is so clear to me, now that time has had its way. But sometimes (like right now) I sit in the cool green parlor, and I remember Doodle.

Colour symbolism varies significantly between cultures and context, but red and green will always be opposite in a scientific sense — unlike many instances of colour symbolism, colour theory does not change from context to context, from culture to culture.

Complementary colours, in stories, can be unambiguous markers of inversion. In other words, something in the story has done a one-eighty.

Young narrator: immoral.

Older, wiser narrator telling this story after many years of reflection: moral.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE SCARLET IBIS”

Apart from peripheral parents there are two characters in this story — big brother, little brother. And, as mentioned above, the big brother has two alters — young character, older narrator.

Take note of the ways in which Hurst compares the children to old people:

- Doodle was born when I was seven and was, from the start, a disappointment. He seemed all head, with a tiny body that was red and shriveled like an old man’s.

- So I dragged him across the cotton field to share the beauty of Old Woman Swamp.

Alice Munro uses this technique a lot. She tends to write across a person’s entire life, in which a young woman is simultaneously an old woman, perhaps because the old woman is looking back. Yet the older woman is right there alongside the younger woman the entire time, affording the reader a compressed but also expanded sense of time. This has the effect of expanding time even within the brevity of the short story format.

Annie Proulx has a different way of achieving similar ends — Proulx tends to write inter-generationally — sometimes across three generations. Then she connects those characters to the landscape, focusing on the magnitude of the landscape, miniaturising the characters.

So what does Hurst achieve in this story, with mention of ‘old man’, ‘old woman’? Perhaps this story is an examination of culpability. Can the narrator’s younger self be excused for this reprehensible behaviour just because he was young? If he imagines himself as a person, simultaneously old and young — just a person — it is harder to justify his own actions. Hence the regretful, confessional tone.

SHORTCOMING OF THE NARRATOR

Values The main character starts with a set of beliefs and values.

This is a story of the patriarchy, in which there is only one way to be a man: Strong, able-bodied and protective. The narrator learned this young. He has learned to be disgusted by anything that doesn’t fit this stereotype. When Doodle cries he is chastised by his father:

“What are you crying for?” asked Daddy, but I couldn’t answer. They didn’t know that I did it just for myself, that Doodle walked only because I was ashamed of having a crippled brother.

It’s the crying itself that’s the problem, so far as the father’s concerned.

This is ultimately a story of remorse. The narrator doesn’t exactly paint a flattering portrait of himself as a young man. How reliable is he as a storyteller? How reliable is his memory? This story isn’t held up as an example of unreliable narration, but one way of reading this story is as a work of self-flagellation. Perhaps there is a lot of sibling guilt in here, guilt that might come with the knowledge that the brothers’ situations could easily have been flipped. It could have been the narrator with the health issues, not the brother. Anyone could think this at any time about anyone, but when it’s your sibling, it’s easier to imagine the flipped positions.

Flipped. Inverse. Opposite. Again with the complementary red and the green, you see.

There’s also embarrassment.

Doodle was five years old when I turned 13. I was embarrassed at having a brother of that age who couldn’t walk, so I set out to teach him.

I put it to you that the narrator has been culturally conditioned to believe that a person can do anything so long as they put their mind to it.

“Oh, yes, you can, Doodle. All you got to do is try.”

I’ve heard it said that this is an idea that exemplifies California. I’ve heard it come out of various actors’ mouths in interviews — they are where they are today because they worked really hard and they had a dream, and because they believed in the dream — like, REALLY believed it — the universe delivered!

#NotAllActors

This 2013 speech by Angelina Jolie garnered attention because she’s saying something too rarely hear from the one per cent: That she is where she is today largely because of… luck. Privilege. Random fortune of circumstance.

If we really believe anyone can do anything if only they set their mind to it, that can lead us to the following conclusion: If you’re living in poverty, homeless, desperate — well, you must have done something wrong. You deserve to be where you are.

If the narrator in “The Scarlet Ibis” can teach his brother to walk, this confirms such a view. He will also no longer be embarrassed by Doodle. He will also feel like Jesus.

Since I had succeeded in teaching Doodle to walk, I began to believe in my own infallibility.

There is inside me (and with sadness I have seen it in others) a knot of cruelty borne by the stream of love. And at times I was mean to Doodle.

The first thing he does wrong:

One time I showed him his casket, telling him how we all believed he would die. When I made him touch the casket, he screamed. And even when we were outside in the bright sunshine he clung to me, crying, “Don’t leave me, Brother! Don’t leave me!”

DESIRE

The main character comes up with a goal toward which all else is sacrificed.

The narrator wants Doodle to walk, for the reasons listed above.

OPPONENT

This goal leads them into direct conflict with an opponent who has a differing set of values but the same goal.

This story isn’t about differing values. I’m confident Doodle would love to walk and run and do everything most other kids can. He simply cannot.

Or is it? Doodle knows to give up trying to run before the narrator does — probably not just out of pain — he knows, viscerally, that ‘trying hard’ won’t do jack. Sometimes it really is a matter of ‘can’t’, as in ‘permanently cannot’.

PLAN

Drive The main character and the opponent take a series of actions to reach the goal.

The brothers go down to Old Woman Swamp and practise walking.

The immoral action is pushing Doodle way too far, causing him pain and physical damage.

In this particular short story there are only two characters, but also the third as I mention above — the much older narrator looking back. Via the psychological insights offered by this extradiegetic character, the same ends are achieved. In other words, the narrator himself guides the reader in our criticism of his younger self.

BIG STRUGGLE

Justification: The main character tries to justify their own actions. They may see the deeper truth and right of the situation at the end of the story, but not yet.

Throughout the narration, the reader is given all the reasons why the narrator keeps going with his plan.

Attack by Ally: The main character’s closest friend makes a strong case that the hero’s methods are wrong.

This is Doodle himself, not saying the narrator’s methods are wrong, but simply impossible.

Obsessive Drive: Galvanised by new revelations about how to win, the main character becomes obsessed with reaching the goal and will do almost anything to succeed.

The parents are pleased with the narrator. The narrator feels less embarrassed. The younger brother looks up to big brother — his behaviours are positively reinforced. No wonder he keeps going.

The narrator pushes his brother beyond his limitations, and we know he isn’t going to back down.

Criticism: Attacks by other characters grow as well.

The father criticises the narrator for crying, though the criticism is for the crying, not for the immoral actions against Doodle. As far as the father is concerned, it’s great that Doodle can walk now.

It’s fully up to the reader to extrapolate that the narrator feels the way he does about Doodle because Doodle is failing to live up to society’s idea of a man. And that these ideas come down from their father.

Justification: The main character vehemently defends their own actions.Doodle was both tired and frightened.

He slipped on the mud and fell. I helped him up, and he smiled at me ashamedly. He had failed and we both knew it. He would never be like the other boys at school.

Battle: The final conflict that decides the goal. Regardless of who wins, the audience learns which values and ideas are superior.

The big struggle is made more intense via the pathetic fallacy of the lightning storm.

ANAGNORISIS

The narrator must choose whether to run home through the rain and lightning, or to go back and help his own brother. He chooses to run without his brother. So he makes an immoral decision, according to common decency.

At that moment, the bird began to flutter. It tumbled down through the bleeding tree and landed at our feet with a thud. Its graceful neck jerked twice and then straightened out, and the bird was still. It lay on the earth like a broken vase of red flowers, and even death could not mar its beauty.

The reader realises before the young narrator does that beauty comes in many different forms. If the scarlet ibis can be beautiful even when it’s dead, why can’t the little brother be beautiful even with his physical disabilities? The older narrator knows that now. He leads the reader to realise this point before he makes his immoral decision to leave his own brother behind in the storm. We therefore judge him negatively, as he has judged himself.

NEW SITUATION

The younger brother is dead; the older brother must live forever with the result of his decision. He immediately knows he chose wrongly.

FURTHER READING

Carson McCullers also wrote a story about two boys from the same family in which the older one abuses the younger. She wrote it when she was still a teenager herself. She called it “Sucker”.

Header image by Vincent van Zalinge