The best horror objects and settings are those you’ll also see peppered throughout cosy stories for children: Circuses, playgrounds, chants and lullabies, hide and seek… scarecrows.

SCARECROWS IN J-HORROR

やぁ〜まだの なぁ〜あかの

いっぽんあしの かかし〜Yaaamada no naaa aka no

Ippon ashi no kakashiiiiThe waaaan legged scarecrow

creepy Japanese scarecrow song

From the middle of Yaaamada

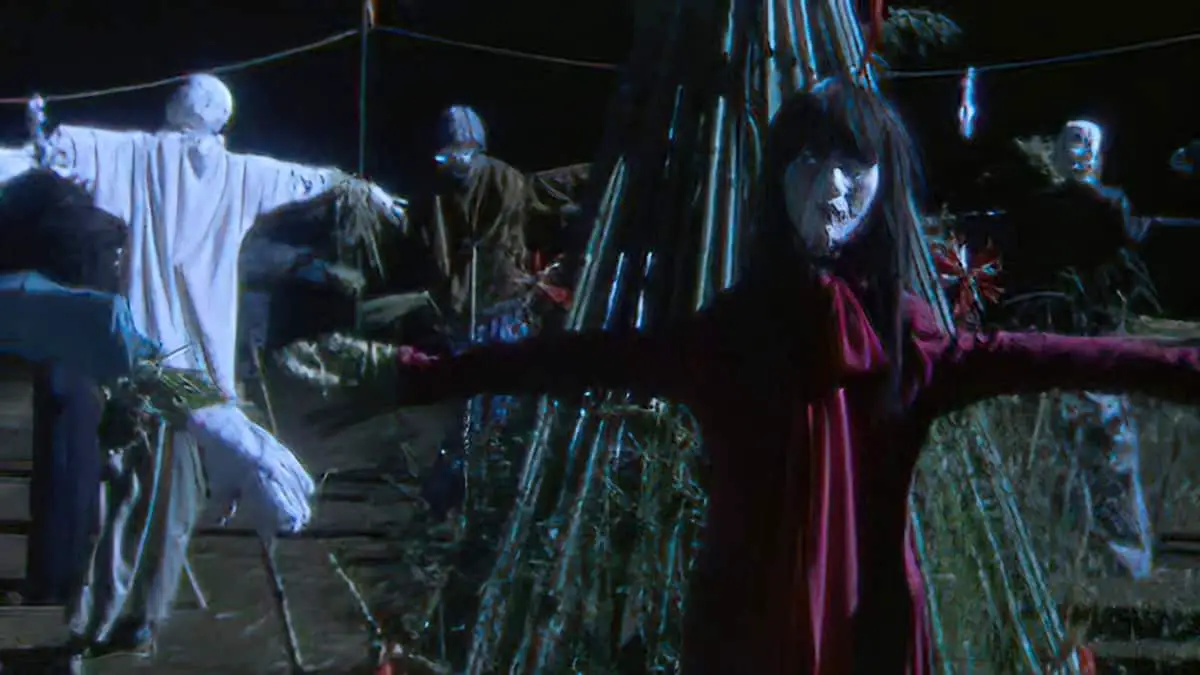

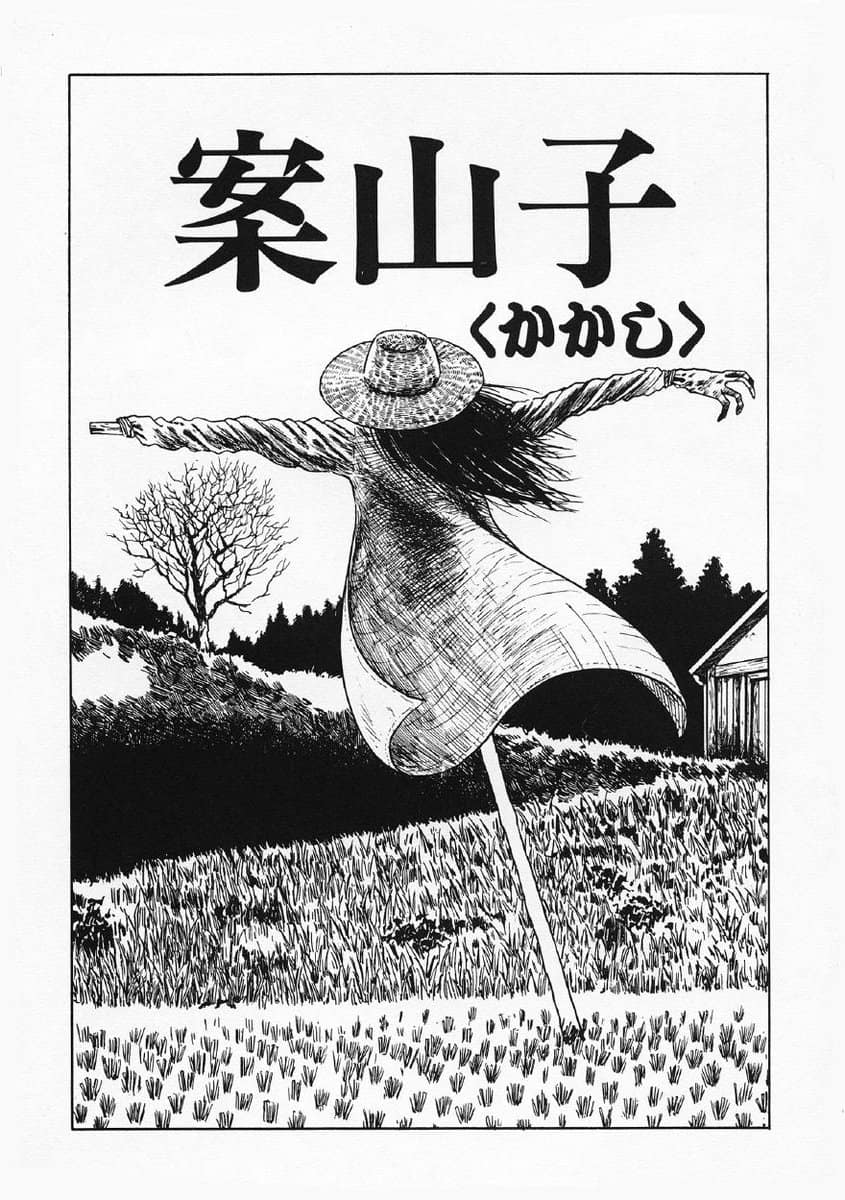

The makers of Japanese horror absolutely see the potential of scarecrows. That’s why Norio Tsuruta directed a film in 2001 called Kakashi (Japanese for scarecrow).

Scarecrows are important to Japanese folklore.

See for example: This Japanese village was on the verge of being deserted, so a resident filled it with life-size dolls. (The Australian headline says ‘dolls’ but the Japanese woman was making scarecrows. Tourists drew faces on them.)

The film is based on a comic by, you guessed it, Junji Ito.

Now of course you see many examples of creepy scarecrows throughout Japan.

I’m sure Totoro was an influence for this one, hugging what appears to be a bus stop.

Scarecrows in Japan: Valley of the Dolls from Japan Visitor has photos of some of the spookiest real life scarecrows you can ever hope to avoid.

Perhaps inspired by the scarecrow, Japanese urban legend has the kunekune. This is a long, slender white guy (or black in the city) who hangs around paddy fields. It seems to be made out of fabric or something, and the name is mimetic, describing how it twists about in the wind. Kind of like one of those windsock dancers used like advertising blimps, I guess.

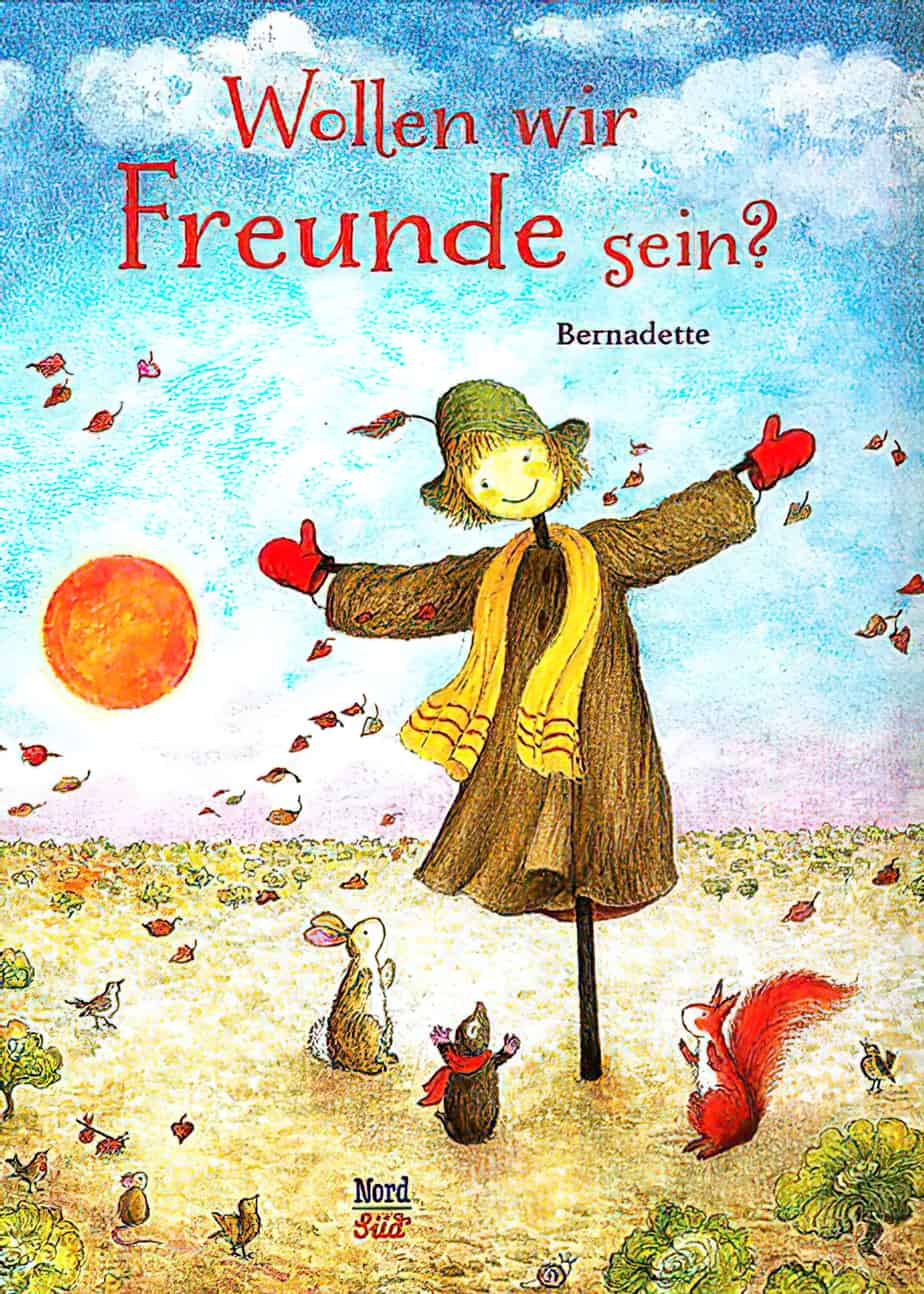

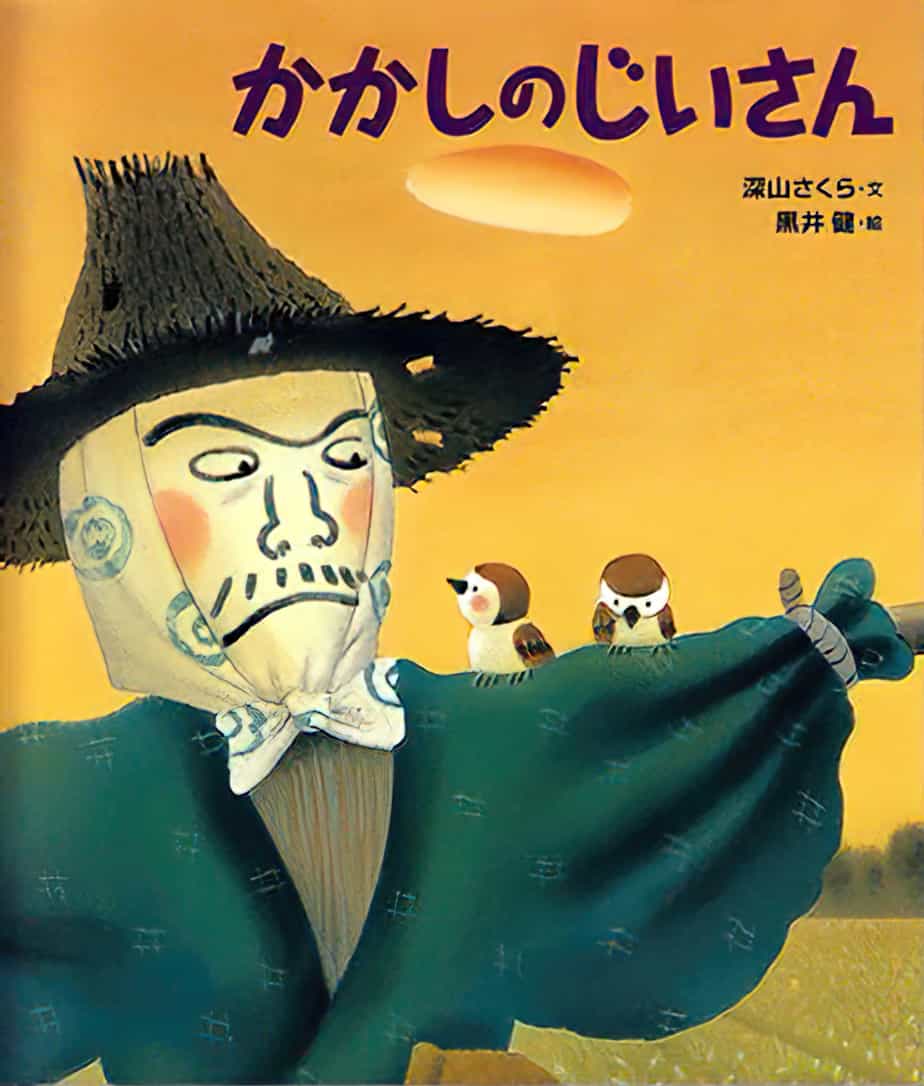

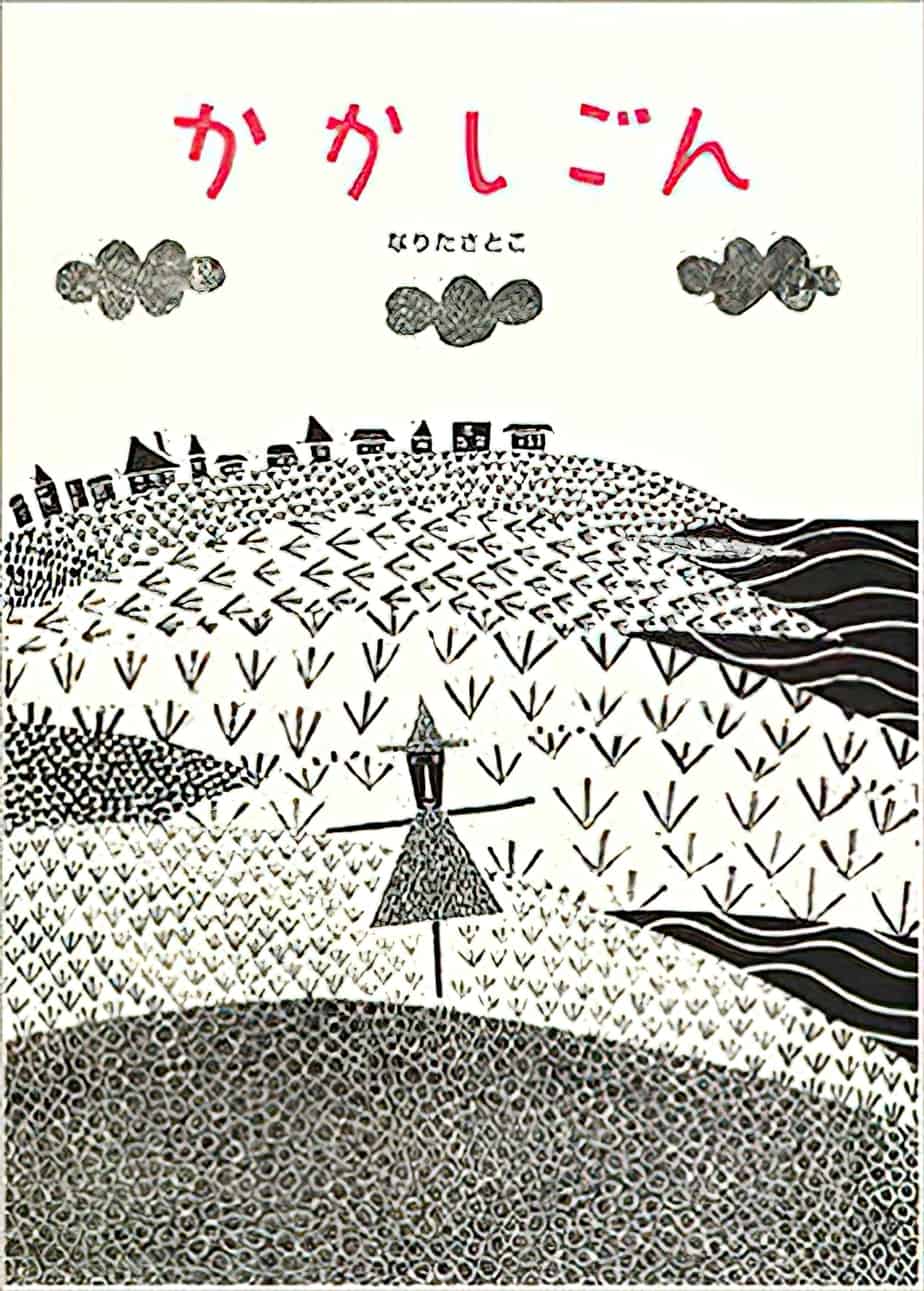

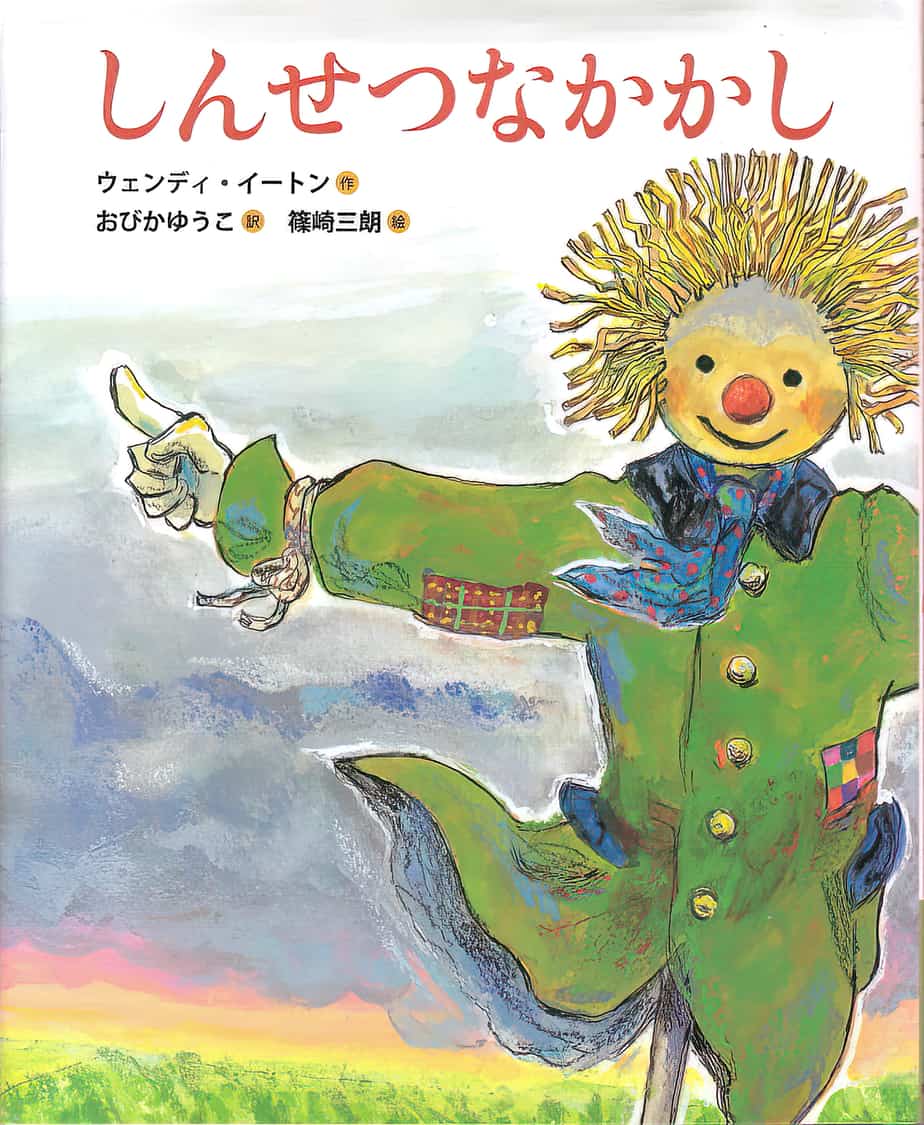

In Japanese children’s books, scarecrows are kindly creatures. Japan also imports books from overseas, and those tend to feature kind scarecrows, too.

Despite the grumpy look on this scarecrow’s face, it is apparently a heartwarming exchange between the scarecrow and the two sparrows.

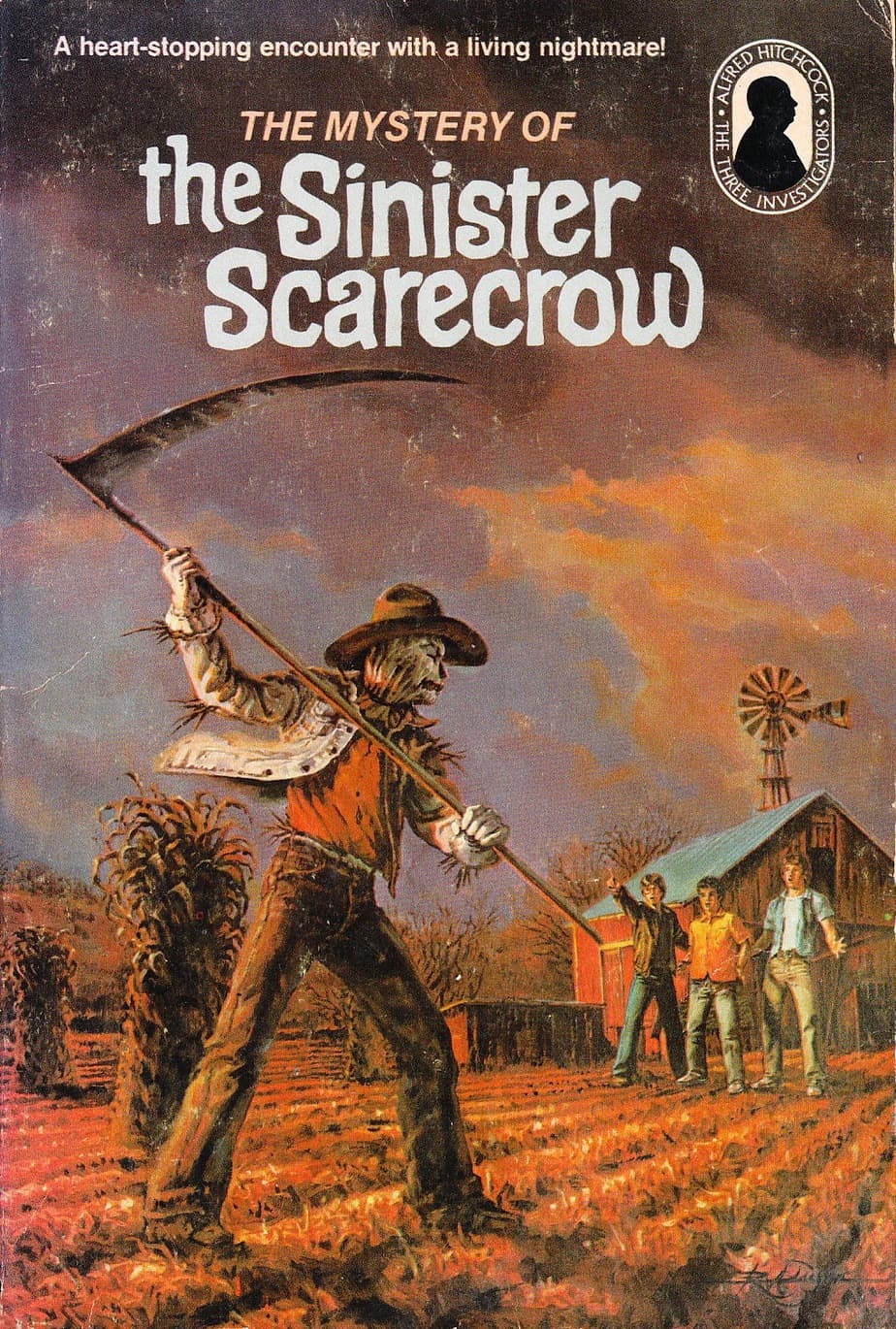

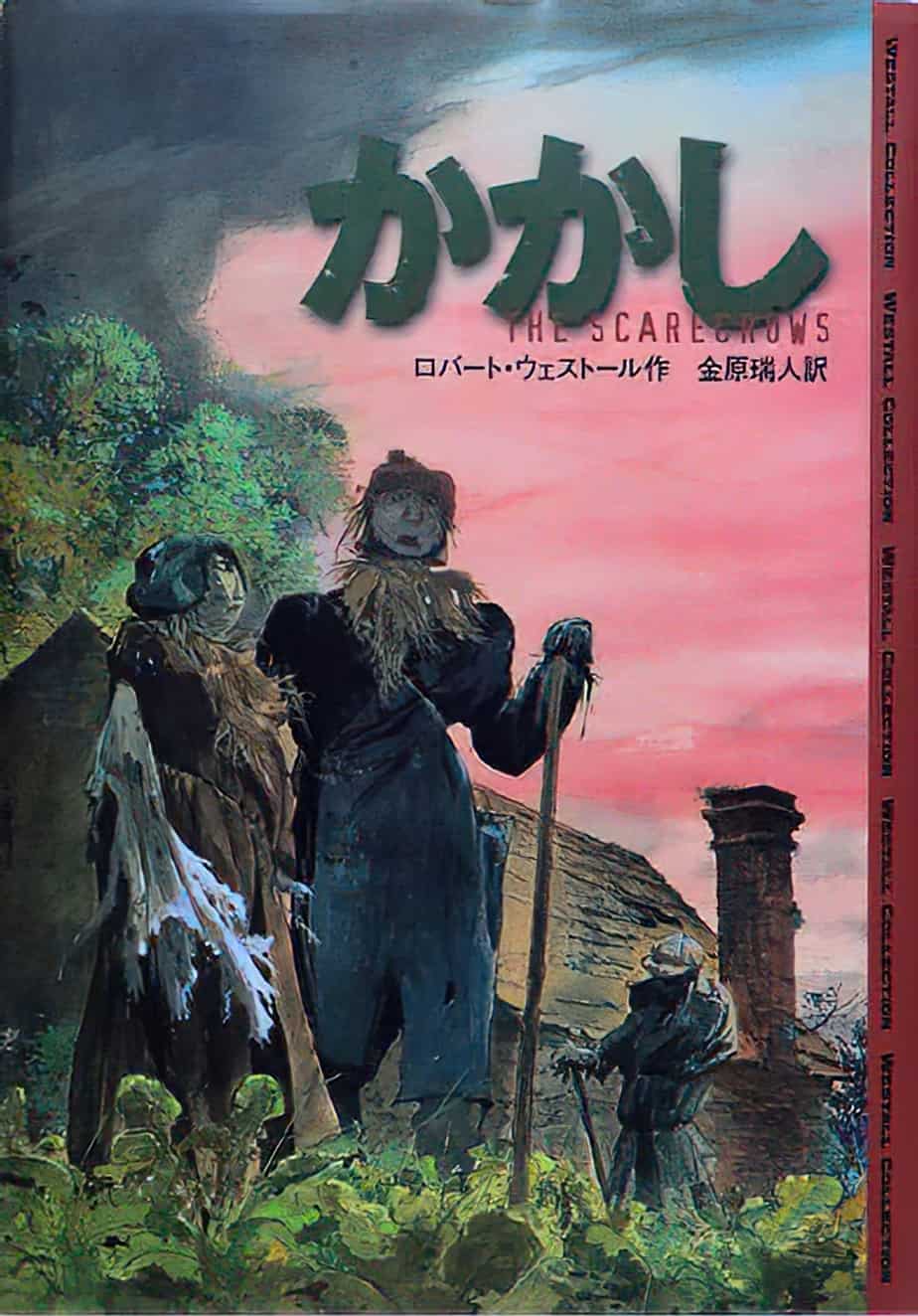

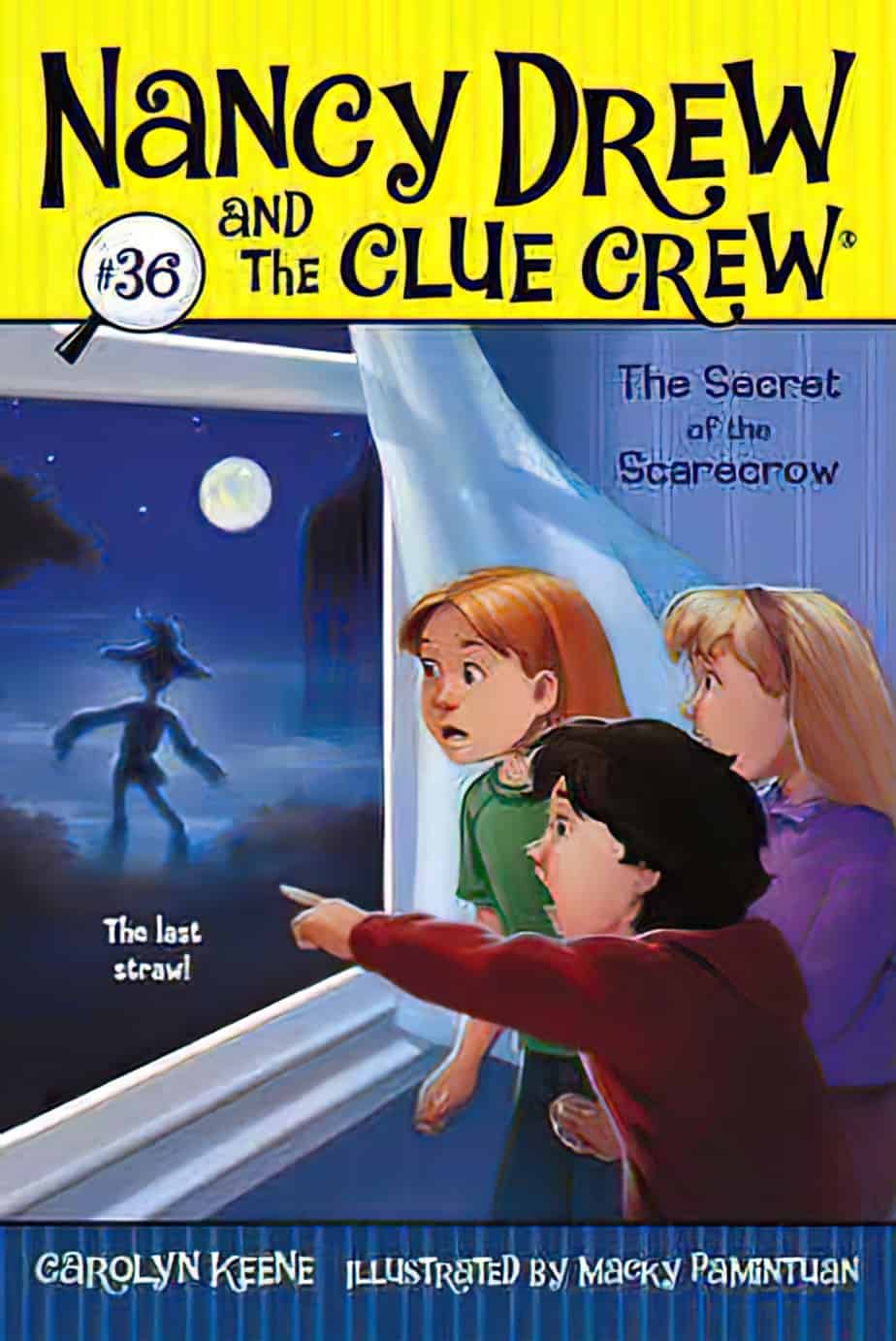

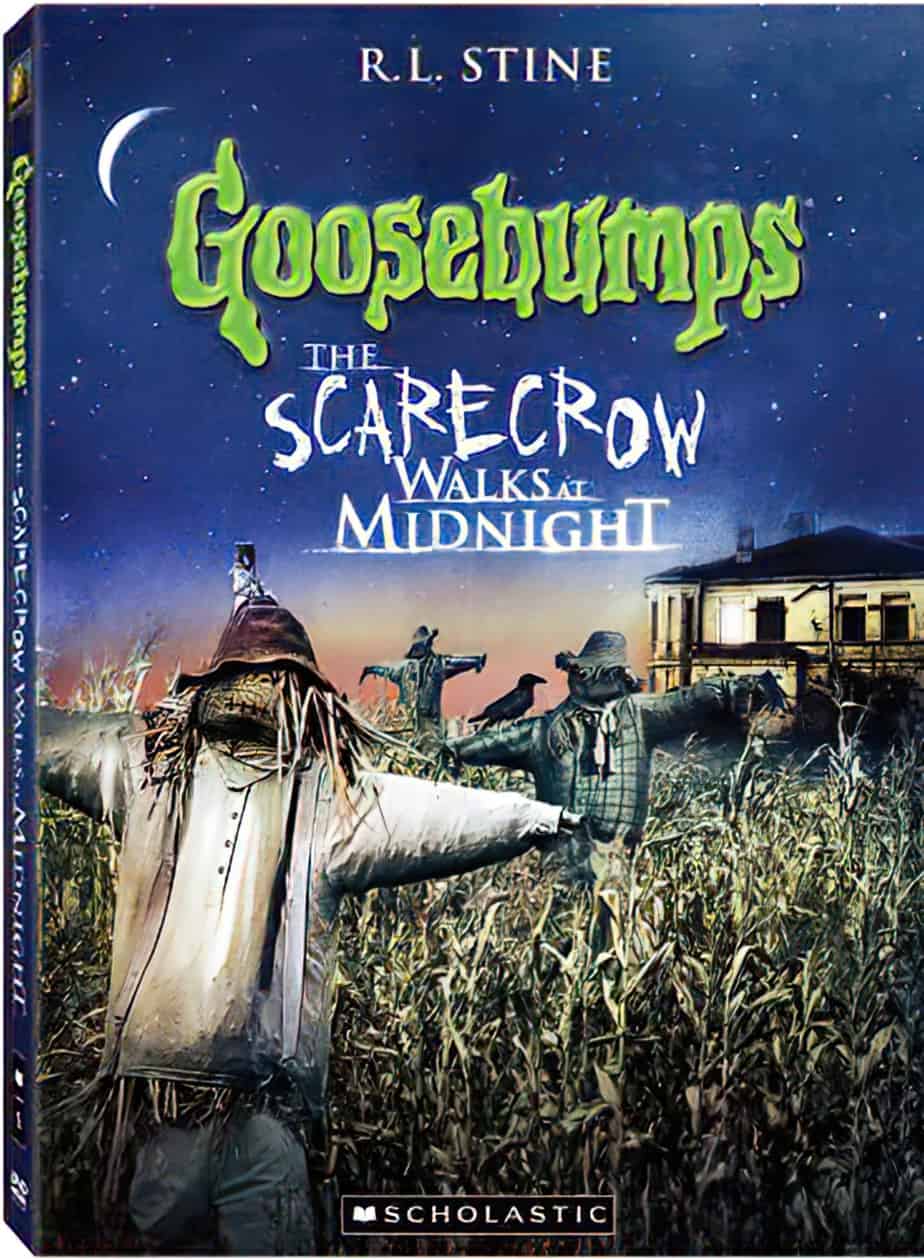

However, when it comes to books for older readers, they work great as baddies.

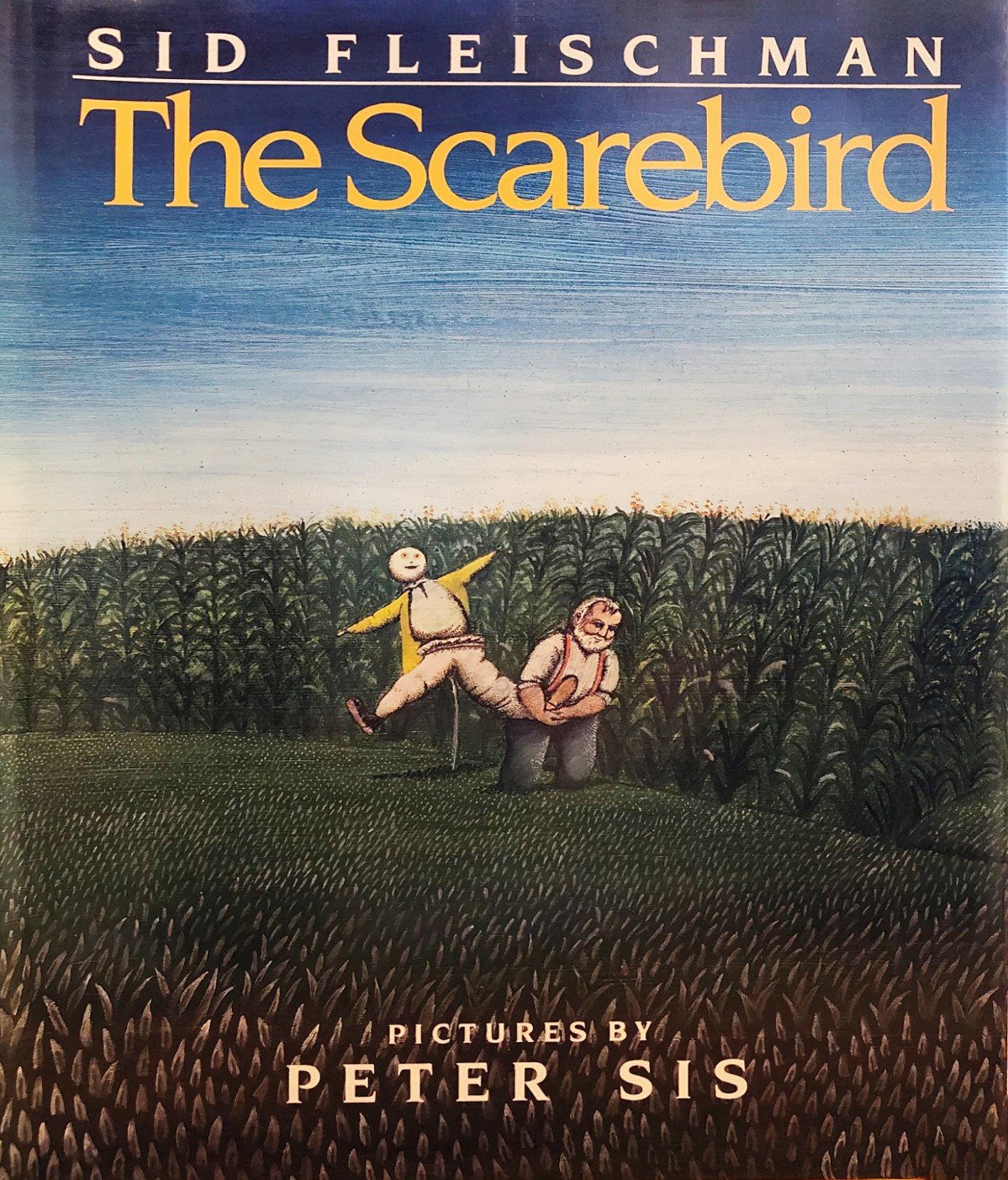

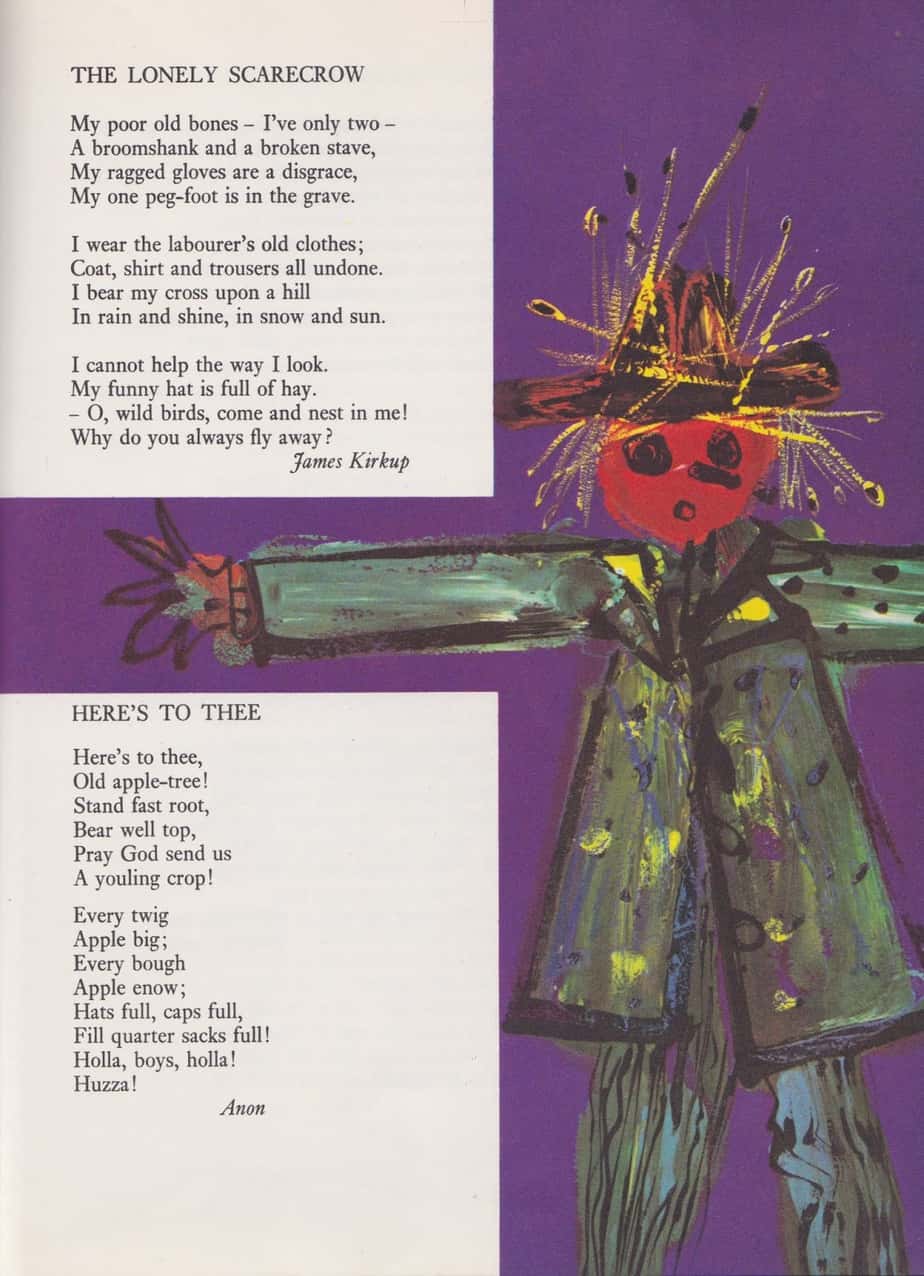

SCARECROWS IN CHILDREN’S BOOKS

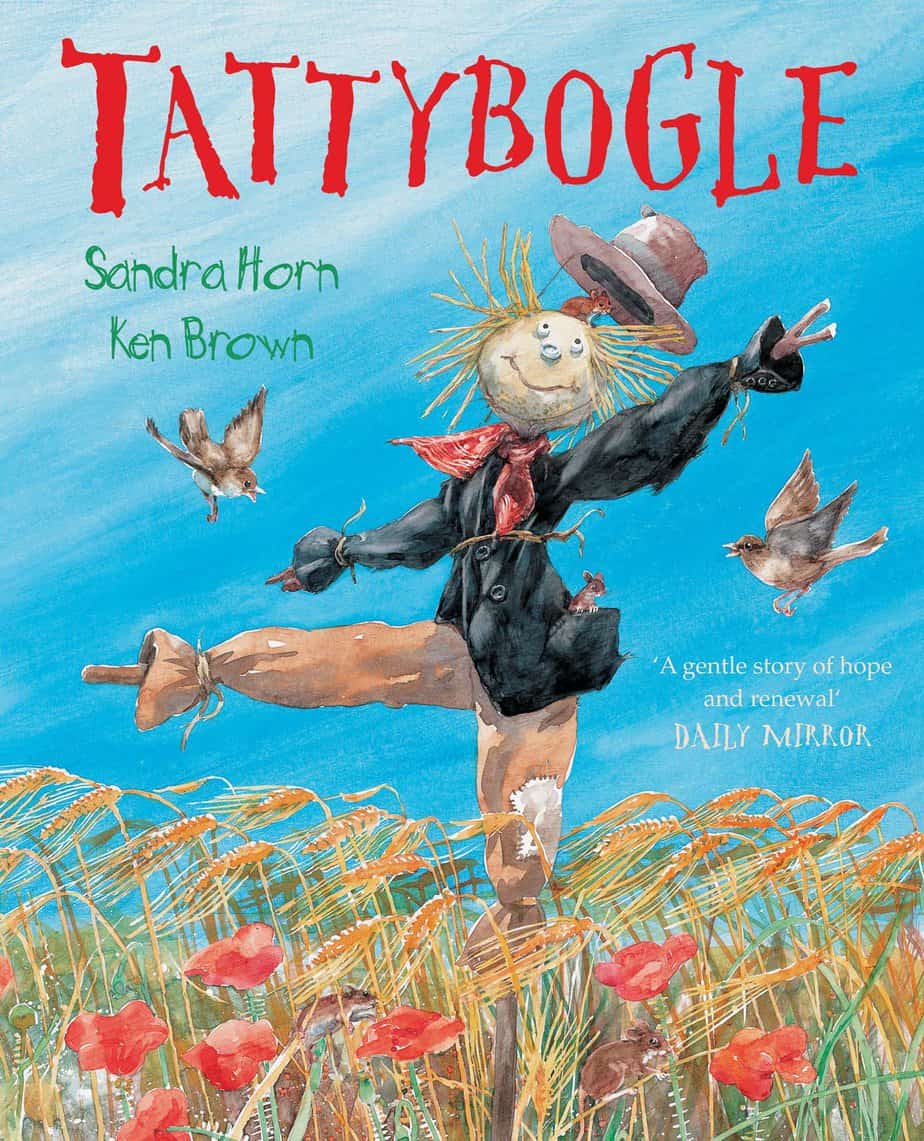

Tattybogle

Perhaps this story has more longevity as a stage play because my daughter’s class performed it last year as part of the Year 2 drama unit here in Australia. The book, however, is out of print.

A bogle, boggle or bogill is a Northumbrian and Scots term for a ghost or folkloric being, used for a variety of related folkloric creatures including:

- Shellycoats

- Barghests

- Brags

- The Hedley Kow

- Giants such as those associated with Cobb’s Causey (also known as “ettins”, “yetuns” or “yotuns” in Northumberland and “Etenes”, “Yttins” or “Ytenes” in the South and South West).

They exist for the simple purpose of perplexing mankind rather than seriously harming or serving them.

Worzel Gummidge

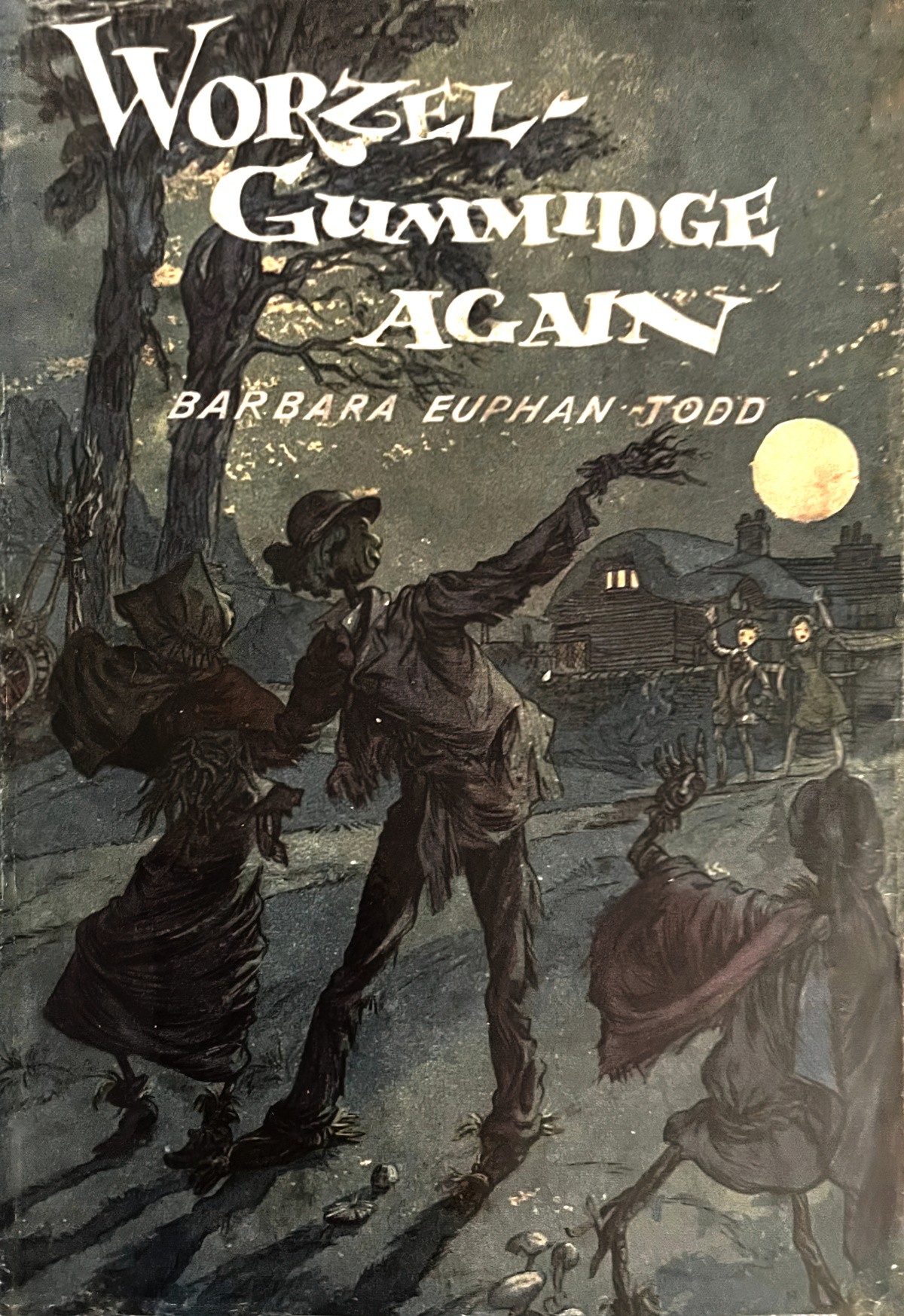

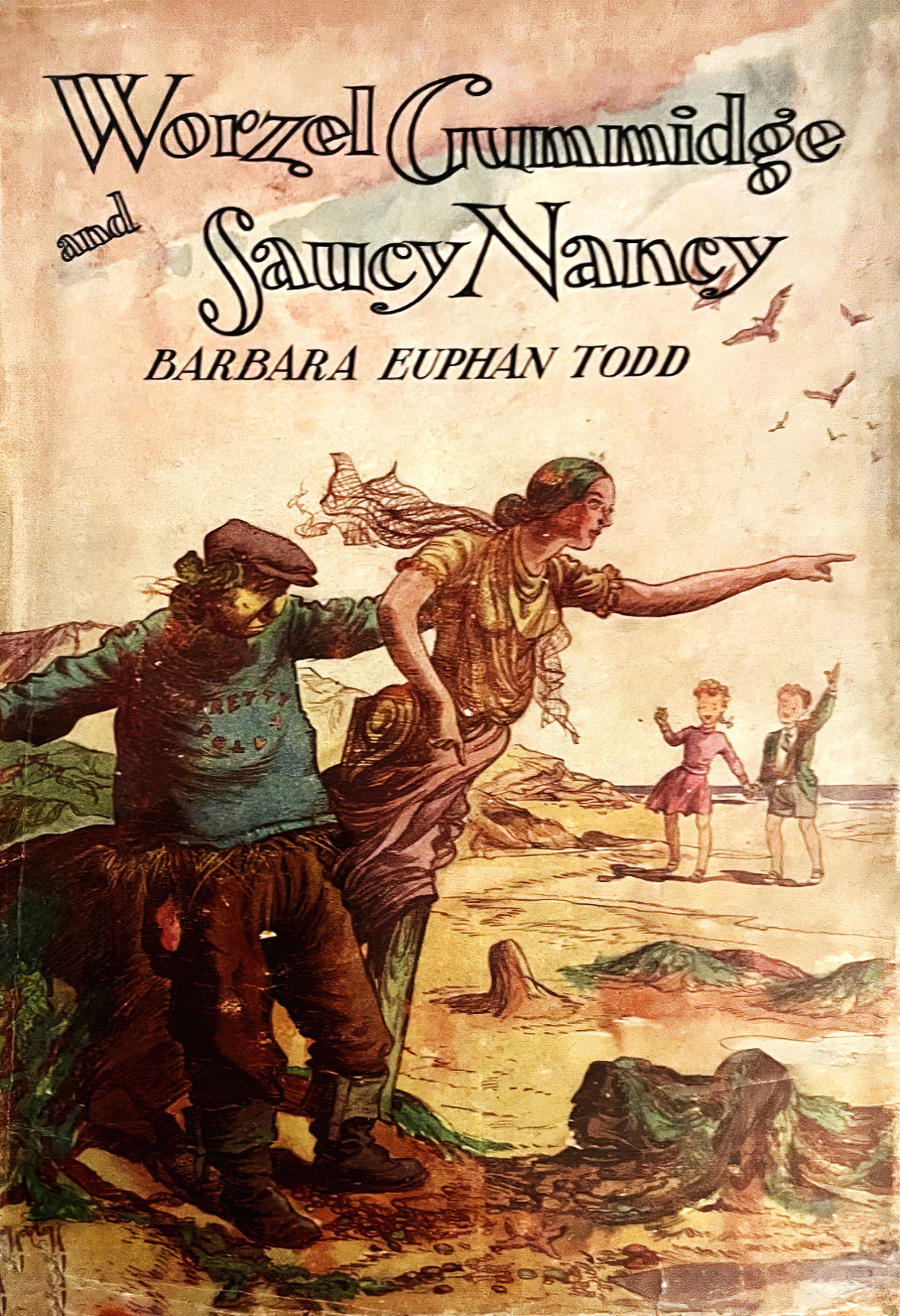

Worzel Gummidge is a walking, talking scarecrow character in British children’s fiction who originally appeared in a series of books by the English novelist Barbara Euphan Todd. This was the first story book published by Puffin Books. There’s a whole series about him.

This show aired in New Zealand when I was growing up in the 80s, though it was already old by the time we got it. I always found the show a bit creepy, and the clip below will show you why.

Also, my mother somehow learned that a rice bubble was used to make Worzel’s warts. This had the effect of putting me off rice bubbles as a breakfast food.

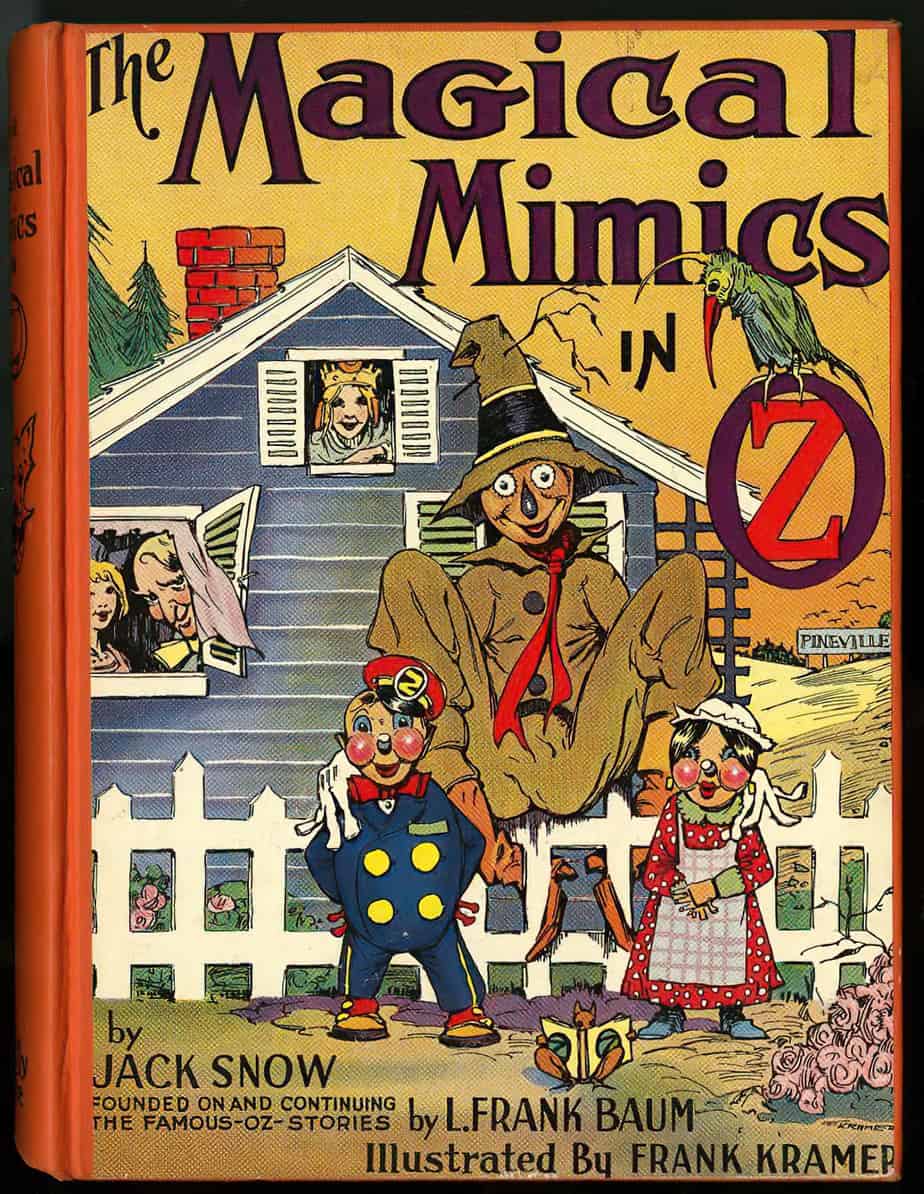

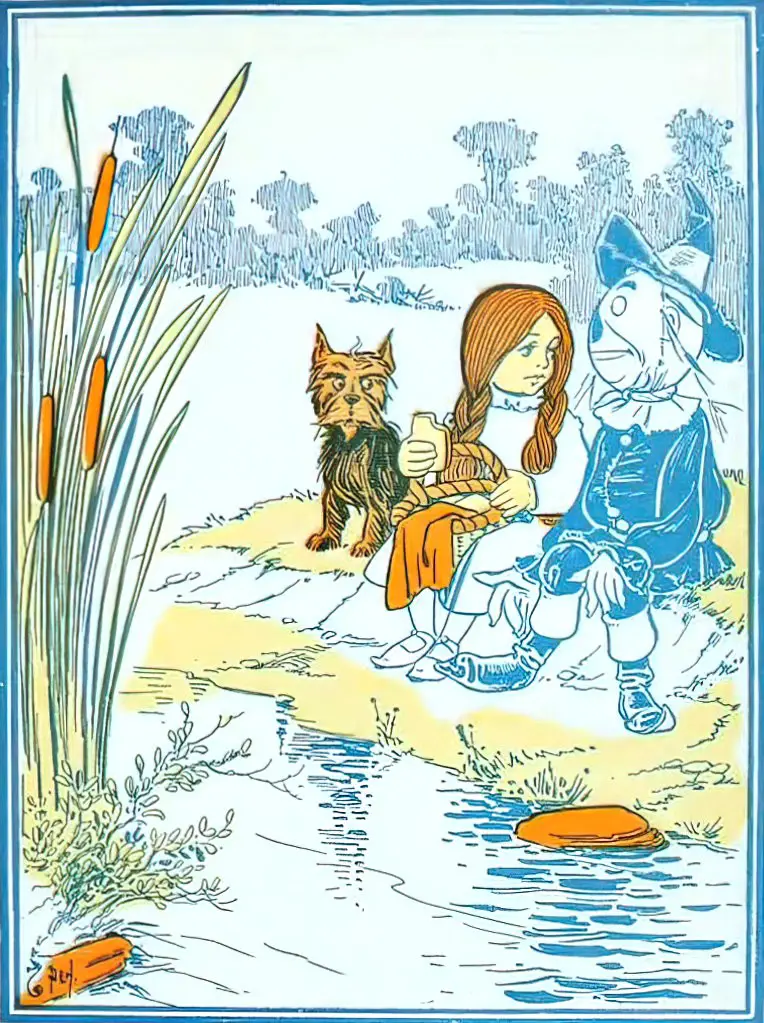

The Wizard Of Oz

Perhaps the most famous literary scarecrow is that invented by L. Frank Baum. The guy without a brain. He gets his own book later in the series, though few have read that.

In Pulp Fiction

Scarecrows can function a bit like clowns — they’re not meant to be scary but because they’re in the shape of a man they tend to slip into uncanny valley.

In Japanese Folklore

In Japan there are scarecrow festivals and there’s even a shrine dedicated to the scarecrow. You can see it here in Google Earth. It’s called Kuehiko Shrine and it’s in Nara, near Osaka.

In direct opposition to L. Frank Baum’s brainless creation, the scarecrow of Japanese folklore is meant to be very knowledgeable. Kuebiko is worshipped as the god of agriculture or scholarship and wisdom, kind of like the Western owl. Here you can see where Japanese visitors have written their wishes on boards and hung them up outside the shrine dedicated to the scarecrow. Is that Western influence there?

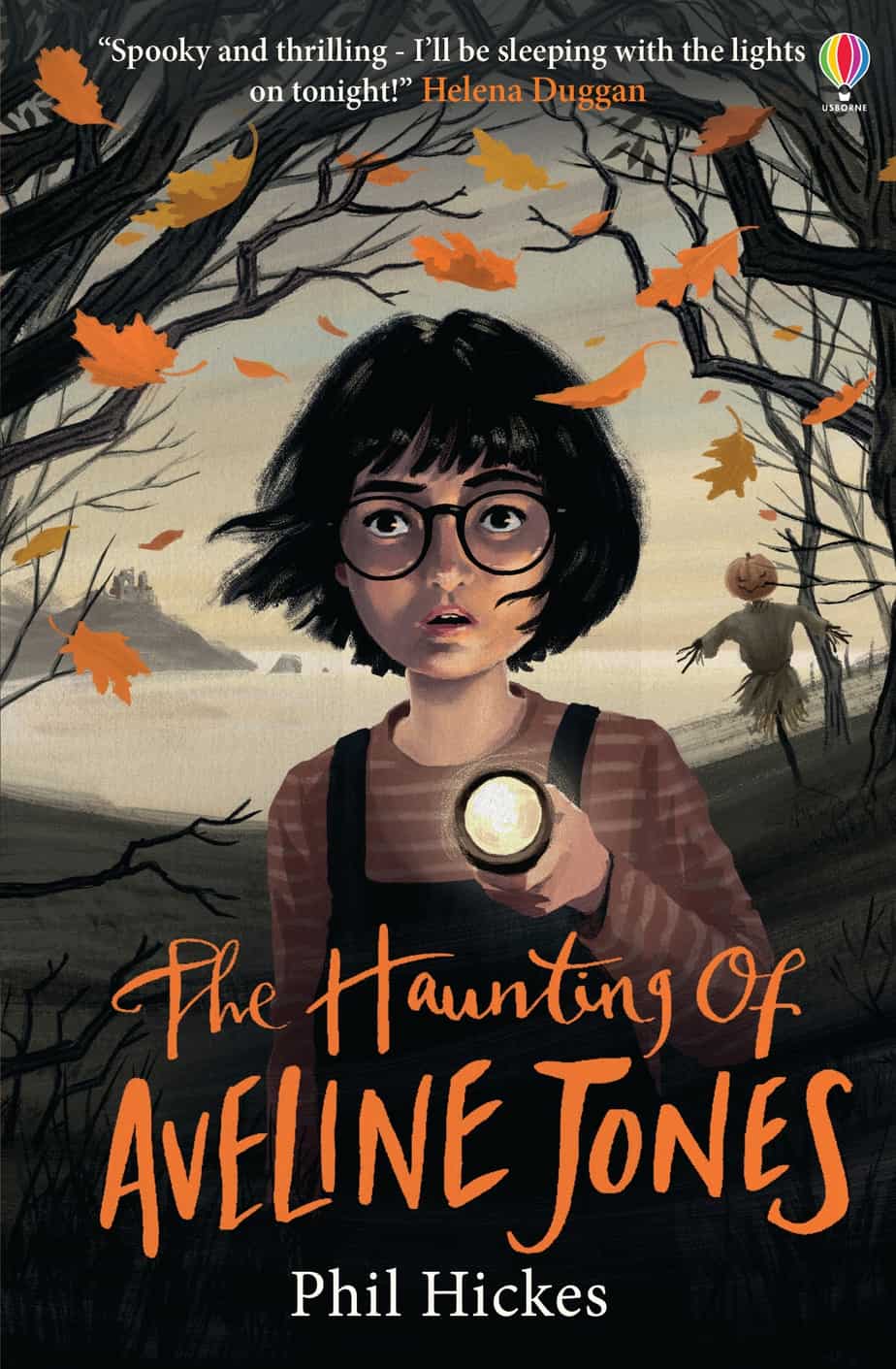

Aveline Jones loves reading ghost stories, so a dreary half-term becomes much more exciting when she discovers a spooky old book. Not only are the stories spine-tingling, but it once belonged to Primrose Penberthy, who vanished mysteriously, never to be seen again. Intrigued, Aveline decides to investigate Primrose’s disappearance.

Now someone… or something, is stirring. And it is looking for Aveline.

When a scarecrow climbs over the garden wall, delivering twelve-year-old orphan Zita Brydgeborn a letter saying she has inherited a distant castle, she jumps at the chance of adventure. But little does she know that she is about to be thrust into a centuries-old battle between good and evil. Blackbird Castle was once home to a powerful dynasty of witches, all of them now dead under mysterious circumstances. Zita is the last of her line. And Zita, unfortunately, doesn’t know the first thing about being a witch.

As she begins her lessons in charms and spells with her guardian, Mrs. Cantanker, Zita makes new allies—a crow, a talking marble head, two castle servants just her age named Bram and Minnifer, and the silent ghost of a green-eyed girl. But who is friend and who is foe? Zita must race to untangle her past and find the magic to save the home she’s always hoped for. Because whatever claimed the souls of her family is now after her.

In a brooding story about jealousy, hatred, murder, and love, Simon is outraged that his mom plans to remarry. He can’t bear the way she and his sister seem to have forgotten his late father. Overwhelmed by hatred, he seeks solace in a nearby abandoned water mill. But another, powerful hatred lingers within its walls. And it is about to be unleashed.