The Sailor Dog by Margaret Wise Brown is a Little Golden Book classic, first published 1953. After the success of Mister Dog, Wise Brown and Garth Williams were paired by the publisher the following year.

The Sailor Dog is basically a Robinsonnade for the preschool set. The Robinsonnade is an adventure story which takes place in a static place, like an island. For more on that, see this post. And for more about the role of islands in storytelling see this one.

ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE SAILOR DOG

Kirkus Reviews described Garth Williams‘ illustrations as ‘sagacious’: having or showing keen mental discernment and good judgement; wise or shrewd.

What is it about Williams’ illustrations that made them so wise?

As many illustrators have emulated since, he includes little side stories, including characters who aren’t mentioned in the text. The snail on the frontispiece illustration is crawling towards the viewer. There’s another identical snail behind, though the body of that one is concealed. This seems to be a deserted island, but is actually teeming with life, though to the newcomer it is hidden.

The second illustration, of the dogs in the car, reminds me very much of the work of Richard Scarry — both men lived at almost exactly the same time. Williams and Scarry both had the knack of drawing detailed illustrations in an era before photographic reference material was so readily available. It is therefore all the more impressive that Williams is able to draw a submarine, sailboat, lighthouse and whatnot. All the same, these are ‘storybook’ versions of such things. The submarine has an American flag waving on the front — the same gag used by The Beatles when they recorded Yellow Submarine in 1966. (Why the subterfuge when you plan to announce your presence?)

Other little ironies include a duck holding a red umbrella and sitting near the water (don’t ducks like water?). On the ship, Scuppers has a bed pan under his bed. Not sure if this is such a great idea for a ship. (We don’t find out what happened to its presumable contents after Scuppers got all caught up in that storm!)

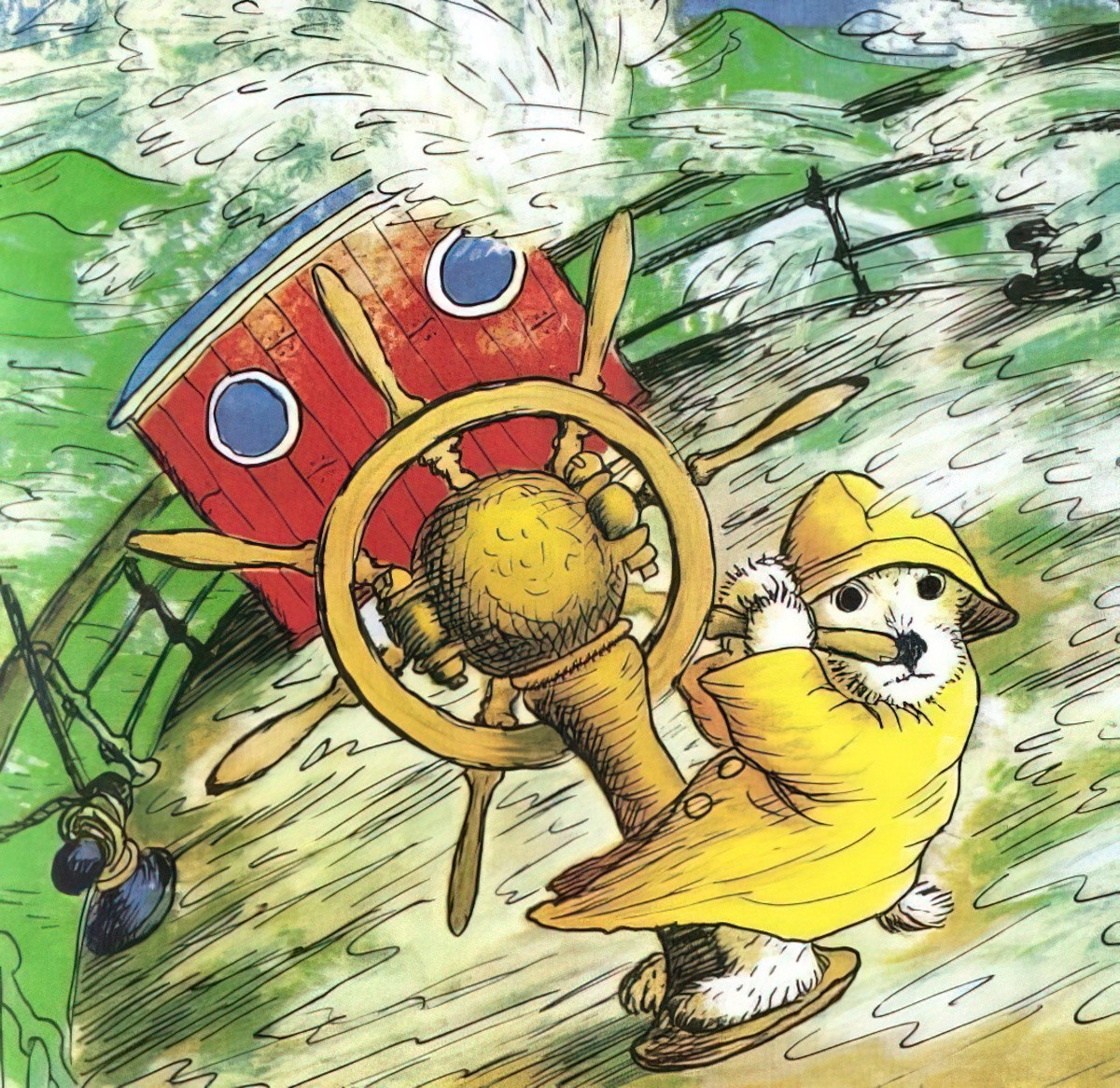

Scuppers himself looks very cute sleeping in his bed, and again later, across pine branches, more like a man than a dog this time. Scuppers becomes increasingly human-like as the story progresses, which was a point not lost on Williams at all — this is part of his arc, culminating in the illustration below, when he puts on clothes:

I write more about this particular image in a post Still Images In Picture Books, in which characters seem to pose for the camera. Most often, this is because the reader is introduced to the character, but this image performs a different function.

Interestingly, Garth Williams doesn’t care too much about continuity — not in the way modern illustrators do. The snails at the beginning are not the same colour as the snails on top of the treasure chest. That’s fine — they’re simply different snails. The lighthouse at the beginning is not the same lighthouse as the one on the closing image — again, fine — they’re different light houses. All the same, I think the modern trend is to maintain a smaller setting within a picture book. Certainly my own instinct would be to illustrate the same snails, the same lighthouse.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE SAILOR DOG

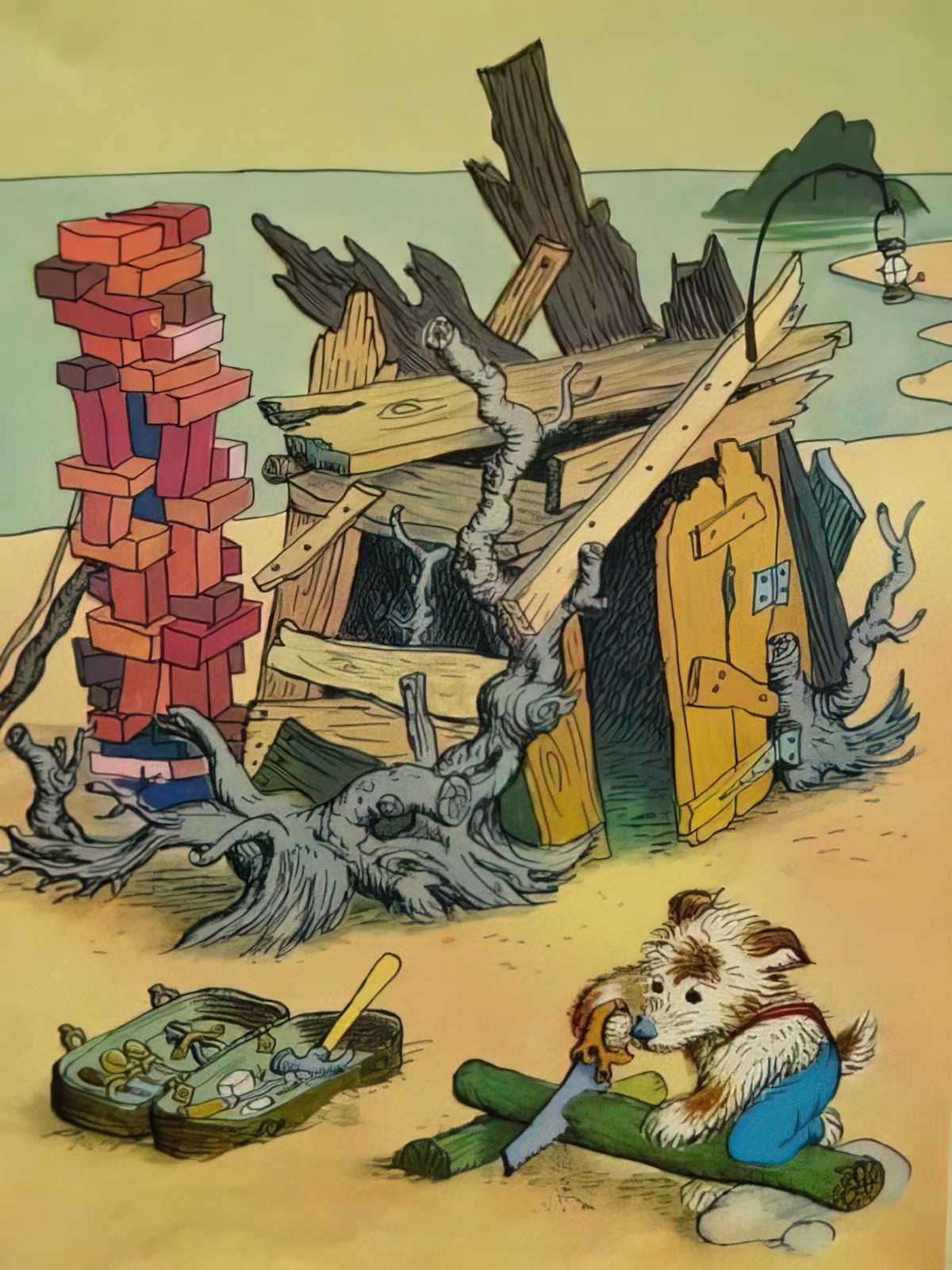

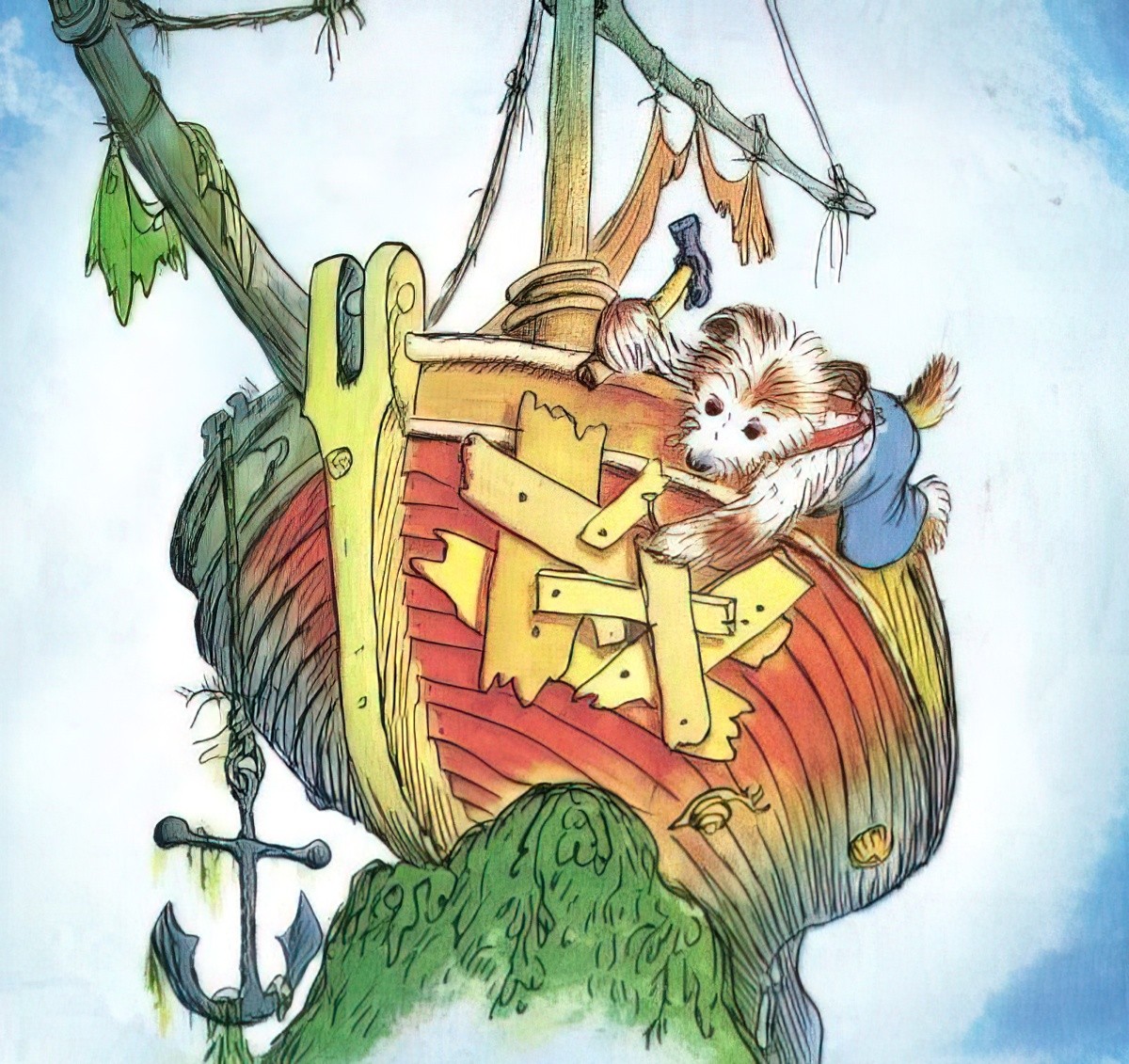

Scuppers the dog has an irresistible urge to sail the sea. His little gaff-rigged sailing boat hardly looks seaworthy, with colorful patches on its sails. Though not a luxurious boat, Scuppers keeps it neat and “ship-shape.” He has a hook for his hat, his rope, and his spyglass. Unfortunately, Scuppers gets shipwrecked after a big storm. Being a resourceful dog, he soon makes a house out of driftwood.

Wikipedia

Eventually, Scuppers repairs his ship and sails away, arriving at a seaport in a foreign land. The street scene is straight from a canine Kasbah. There are lady dogs dressed in full-length robes with everything but their eyes, paws, and tails covered, balancing jars on their heads. Scuppers needs new clothes after all his travels. He tries on various hats and shoes of different shapes and colors.

Life at sea soon calls Scuppers back to his boat. After stowing all his gear in its right place, he is back “where he wants to be — a sailor sailing the deep green sea.”

SHORTCOMING

Scuppers proves himself comically adept in this inversion of a Robinsonnade tale, so he doesn’t have a shortcoming or a need. In that, he is identical to Mister Dog. But he does have a problem, which is all we need to start a story, especially a picture book. His problem is that he wants to be a sailor, but he’s not a proper sailor (yet). In order to be a proper sailor, he’ll need sailing experience.

DESIRE

He wants to be a sailor.

OPPONENT

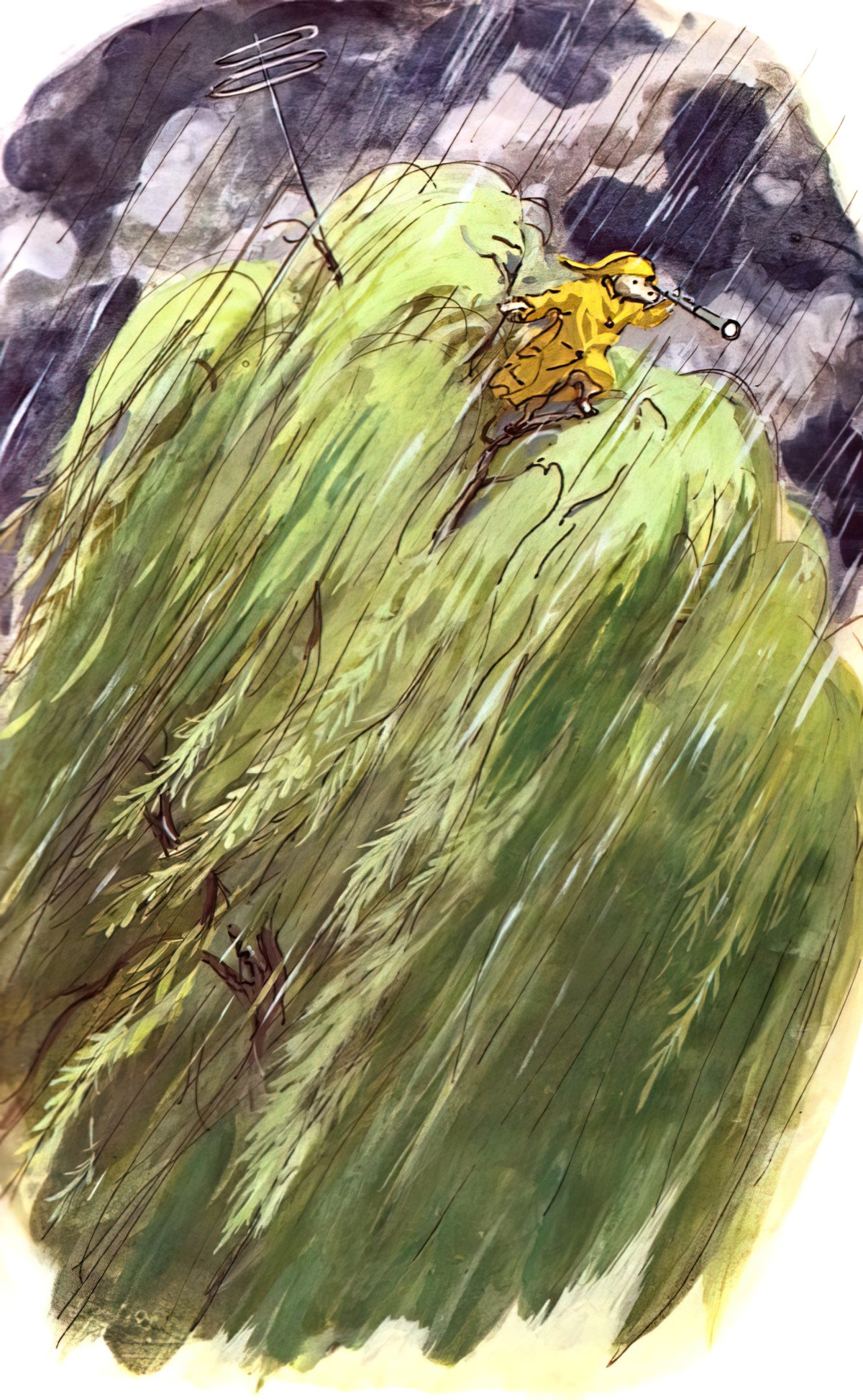

There is no anthropomorphised opponent in this story, because Margaret Wise Brown does her own thing, always. Instead, the opponent is simply the storm.

If there’s any kind of mythic narrative in which a human opponent is absent, it is the Robinsonnade. The very essence of a Robinsonnade is ‘man alone’, at least for a large part of the story. This makes these stories difficult to write. If there’s no villain, what will you use for your human-interest opposition? For longer works, ‘nature as opposition’ is never enough on its own to create a fascinating character web.

PLAN

First Scuppers builds a house. This speaks directly to the hygge nature of picture books. When my daughter was a preschooler I noticed that in her play (whether with a dollhouse or in computer games like Terraria), the first tasks she set herself involved making herself a bed. Then, when disaster struck (it always did), her character-self could retreat to the safety of home.

This need for security is depicted in fantasy. I remember at about the age of ten writing my own Robinsonnade (not that I knew that word). It was called “Fruitiful Island” and not much happens except my main character is shipwrecked onto an island which turns out to be a bounty of delicious goods. (I didn’t realise the value of narrative conflict back then and the story languished, half-finished, but a fulsome utopia in my own mind.)

The enduring popularity of The Sailor Dog tells me I’m not the only one with the shipwrecked on an island fantasy, in which we build our lives again from scratch, taking pleasure and pride in our own efforts.

If he could build a house, he could mend the whole ship.

I find this line hilarious. One could say exactly the same thing of Robinson Crusoe, who made such a fine old life for himself on his island, why the hell couldn’t he build himself a ship to get on out of there, if he had so many skills?

Instead, Crusoe sat around and waited for an English ship to appear — the colonialist’s equivalent of the woodcutter in a Little Red Riding Hood tale, as retold by a pair of patriarchal brothers.

In short, Scuppers is far more self-determined than Robinson Crusoe ever was. That seems to be the way of it for children’s characters. Writers can create adult characters for adults who sit around and wait for things to happen to them before springing into action, but if you’re writing child characters for a child audience, they’ll probably be up-and-at-em from the get go. Adults are mullers; children are doers.

BIG STRUGGLE

We might assume in a Robinsonnade that the Battle scene happens against the backdrop of the big storm which gets Scuppers shipwrecked in the first place. This would indeed make for wonderful pathetic fallacy. But the shipwreck is not the main thing:

Next morning he was shipwrecked. Too big a storm blew out of the sky. The anchor dragged, and the ship crashed onto the rocks. There was a big hole in it.

That’s as close as Margaret Wise Brown gets to a Battle sequence. But for this story, it’s more of a ‘means of transport’, getting Scuppers to the island.

In a classic Robinsonnade narrative, the Battle happens on the island, as the hero fights for his life, trying to find food, coming close to starvation and whatnot. This aspect of the Robinsonnade is the most interesting for an adult audience. We see the hero slowly lose his grip in Castaway, starring Tom Hanks. In Castaway, the hero almost loses himself.

But in a Margaret Wise Brown story, Scuppers had no problems on the island. He sleeps, he mends his own ship, he sails back into civilisation. Scuppers has literally zero problems surviving on the island. This is part of the gag above. This is what makes The Sailor Dog a parody of the Robinsonnade rather than a true Robinsonnade. It works as a story because the elements are all there — the emphasis is simply skewed.

ANAGNORISIS

The Anagnorisis is that Scuppers is a proper sailor now. He’s survived a shipwreck, made a life for himself on a (semi-)deserted island, and now he’s wearing sailor clothes to boot. The scene in which Scupper hangs all his new sailor clothes on his hook is the Anagnorisis scene.

Of course, the audience must have the world knowledge to know what a sailor’s uniform looks like. Perhaps a modern audience needs this pointed out. In 1953 I suspect the sight of men in their defence force uniforms were far more common around the world.

NEW SITUATION

And here he is where he wants to be—

a sailor sailing the deep green sea.

The story actually closes with his song. The song underscores the character arc, in case we missed it:

I am Scuppers the Sailor Dog—

I’m Scuppers the Sailor Dog—

I can sail in a gale

right over a whale

under full sail

in a fog.

and so on. The second verse is funnier, but I recommend you get your hands on the book.

FURTHER READING

If you enjoy the character of Scuppers, you may also enjoy the retro children’s book called Miss Twiggley’s Tree by Dorothea Warren Fox, published in 1966.