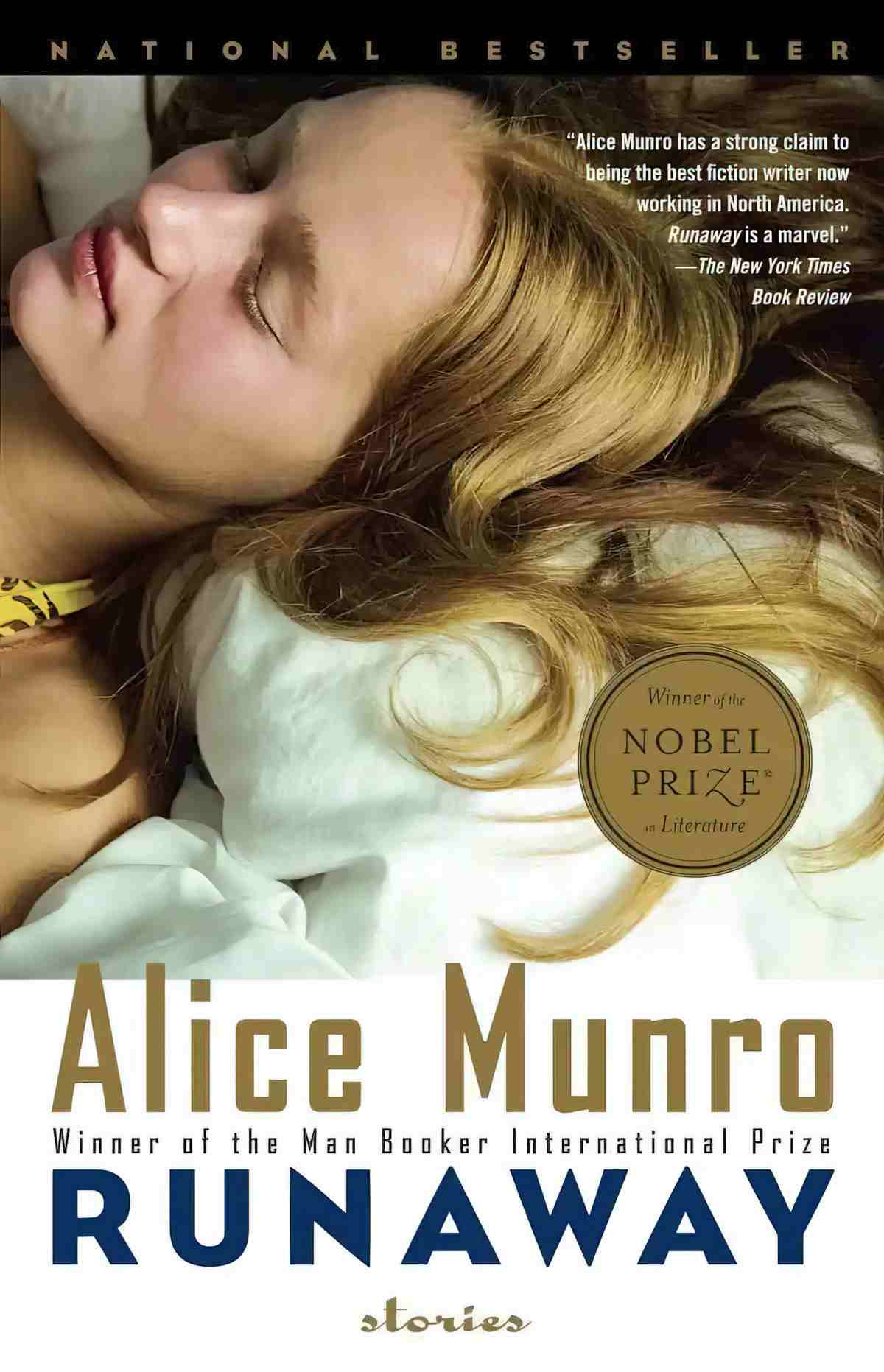

“Runaway” is the first short story of Alice Munro’s 2004 collection. It was also published in The New Yorker, where you can read it online. “Runaway” makes for a great mentor text for the following reasons:

- Nuance of human motivations. The desire is at the ‘complex’ end of the spectrum — our main character doesn’t actually know what it is she wants. How do you write that kind of character, when we’re told over and over that our main character has to ‘want’ something? Carla is a great case study.

- A Plan which is actually a fantasy plan, but still works as a proxy.

- A Battle scene which follows the ‘real’ big struggle.

- A Anagnorisis had by two characters first presented as ‘parallels’, now revealed to be ‘inverse’ characters. One achieves more insight into her own psychology; the other — we extrapolate — never will. The latter does realise something — a proxy revelation — just not about herself.

SETTING OF “RUNAWAY”

Stories which place a rich and poor character side-by-side make for excellent conflict. Annie Proulx made the most of this in her collection Heart Songs, in which rich city folk come into poor rural areas and buy up expensive properties, trying to bend the existing world to their whims — and often succeeding, with casualties.

Rural areas are perhaps the most realistic place you’ll find rich and poor living literally side by side. Farmers themselves fall outside the traditional socioeconomic delineations used by economists — while wealthy in assets they are often living frugally. In Munro’s short story “Runaway”, we have a genuinely well-off woman of the academic class living on a bit of land next to a young couple with nothing but dreams of running a horse farm. Clark has managed to save enough to buy the land, but they live in a trailer on it. This rich-next-to-poor scenario is common in rural areas — the owner/renter divide is very real in urban areas too, but amplified in the country.

The country is Canada, the nearest city is Toronto — Munro’s familiar territory. We can expect harsh season changes with plenty of snow, though in “Runaway” the fog is utilised to create a faux-supernatural event which aids in character epiphany. Overall we’re told ‘this was the summer of rain and more rain’. I did wonder if it can be raining and foggy at the same time — here is the answer to that. (It’s low humidity where I live, which explains why I’ve never seen heavy rain and fog at the same time.)

The character of Clark is connected to the rain:

But they talked about [their extortion plan] the next day, and the next and the next. He sometimes got notions like this that were not practicable, which might even be illegal. He talked about them with growing excitement and then—she wasn’t sure why—he dropped them. If the rain had stopped, if this had turned into something like a normal summer, he might have let this idea go the way of the others. But that had not happened…

Clark is like the rain in that he is relentless. He also reminds Carla of the rain because in her eyes he is being unusually relentless. He drops mad ideas, but not this one. But I don’t believe the reader is meant to see this episode as unusual — this is Carla’s new normal. We know this by the end of the story.

Plot wise, the rain also prevents Carla and Clark from earning money in their horse business. It also contrasts with sunny, laidback Greece, where Mrs Jamieson has just come from. Mrs Jamieson lives in a different world (even when she’s home in Canada).

STORY STRUCTURE OF “RUNAWAY”

SHORTCOMING

For my purposes, the main character of “Runaway” is Carla. But you could equally argue that this story stars Mrs Jamieson equally, because both Carla and Jamieson learn something. They both undergo a character arc.

Carla’s psychological shortcoming: She is naive, unable to stand up for what she knows to be right in her marriage, is isolated from her family (and effective orphan).

She also has a clear moral shortcoming: She is playing along with Clark’s plan to extort money from a recently widowed neighbour, and to tarnish the reputation of a dead man.

Munro encourages us to dislike Carla very much. Then we see a complete turn-around once Carla gets to Mrs Jamieson’s house. She’s either had a spontaneous change of heart, or always planned to spin a different story, casting her own husband in the bad light, but in any case, Carla is dangerously flaky. She’s not just dangerous to herself, but to those around her.

We can’t speak of Carla without mention of the goat. For storytelling purposes (though not in any sort of fantasy way), the goat is the spirit animal of Carla. They are linked visually by the ‘dandelion’ descriptor — Carla’s hair looks like a dandelion, because of the strands too short to fit into her braid. Later, the goat turns up and ‘transformed itself into soemthing spiky and radiant. First a live dandelion ball, tumbling forward…’ Then of course there is the running away from a violent man aspect, and their mutual return.

DESIRE

Surface desire: Carla wants money, because she and her husband are lacking funds to live. They’re not finding it easy to muster up coinage for the laundromat, instead using musty towels.

Deeper desire: Carla wants to hide in the security of her existing marriage, even though that means much sacrifice on her part, with her husband’s volatile nature having a direct influence on the amount of custom they can expect, among other things.

OPPONENT

Alice Munro introduces the opponent as a mystery in the opening paragraph. We wonder who Mrs Jamieson is and why Carla is so interested in her. The existing corpus of narrative may lead us toward the conjecture that Mrs Jamieson has been sexually involved with Carla’s husband. I think Munro may intend this, because she focuses on Mrs Jamieson’s physical description:

Carla got a glimpse of a tanned arm bare to the shoulder, hair bleached a lighter colour than it had been before, more white now than silver blonde

But if we think that, Munro will soon subvert those expectations. Mrs Jamieson is an example of the most humane type of opposition: Like a parent in a children’s book, she does want what’s best for Carla. But because Carla wants something different, that casts Mrs Jamieson as an opponent.

In opposition to Carla’s desire, Mrs Jamieson wants Carla to leave her husband. But more selfishly, she probably wants to feel responsible for someone else and immerse herself for a little while in someone else’s problems, helping Carla to ‘fix’ them, as displacement activity after losing her own husband.

In some ways, Carla and Mrs Jamieson are living in parallel — literally side by side. But they are revealed to be the inverse of each other. Young/wise, wealthy/poor, uneducated/educated. Importantly for this plot, one has just lost her husband — the other fights to keep hers, no matter what.

Carla’s husband Clark is an interesting romantic opponent because of his duality: He is friendly with people at first then turns on a dime. We will see this in action during the Battle with Mrs Jamieson (when the goat reappears), but Munro gives us some vignettes which describe his character beautifully — Clark in the pharmacy, Clark alienating clients, Clark almost scalding a child with coffee which he then denies.

PLAN

Carla and Clark, though mostly Clark, concoct a fantasy plan. They will extract money from Mrs Jamieson by saying her semi-famous dead husband was sexually inappropriate with Carla. At first I was a little wary of this storyline. I’m absolutely done with stories about women who ‘cry rape’ for personal gain. I’m done with Gone Girl stories, in other words. They contribute to a mainstream, real-life narrative (false) in which people really do think women lie about rape on a regular basis. But Alice Munro — of course — has a far more nuanced understanding of human nature. Carla is playing with a kind of rape fantasy, and it’s the husband who picks this up and runs with it. This does actually accord with what tends to happen in the few real-life instances of false rape accusations — about half of the total of false rape accusations are lodged on behalf of a woman, not by the woman herself.

I’ve noticed that for storytelling purposes, an imagined or fantasy plan is as effective as an actual plan, because the reader doesn’t know at first that it’s nothing but fantasy, so the fantasy plan still works to propel the action along.

BIG STRUGGLE

Carla gets her Battle, but it doesn’t look like a fight — Carla’s big struggleground is sitting in Mrs Jamieson’s house playing at posh ladies, probably turning over in her head whether she should leave Clark or not. I believe she means to leave Clark at the time.

The clear Battle Scene (the scene that looks like a Battle) is not between Carla and another character but between Clark and Mrs Jamieson. This feels very true to Carla’s character — Carla is staying with Clark because she knows he’s always going to fight her big struggles for her, whether those big struggles are worth fighting or not.

ANAGNORISIS

It’s not until Carla leaves Mrs Jamieson’s house she realises she can’t leave Clark. But the reader is kept out of Carla’s head for that little epiphany. Instead we learn of this decision at the same time Mrs Jamieson learns it. By this stage of the story, our sympathies are clearly with Mrs Jamieson. We know far more than she does about the whole situation as Munro has kept us in audience superior position, starting off with Clark and Carla, and only later switching to close third person on Mrs Jamieson as she goes to sleep on the couch and is rudely awakened by Clark.

It can be a real writing challenge, depicting the Self-Revelation phase in a short story. The writer doesn’t have much room to lead up to it, and it can feel contrived when a character suddenly realises something without much in the way of preamble. In “Runaway” Alice Munro gets around the ‘suddenness’ of Mrs Jamieson’s anagnorisis: that she has been too heavily involved in Carla’s life, by showing the reader the note that she left for Carla afterwards. Again, this works for the character because Mrs Jamieson is a writerly, academic type with sufficient life experience to be able to craft an apology.

Carla’s epiphany is more brutal, and is to do with Clark, not Mrs Jamieson. She realises Clark may have killed her beloved goat. Yet for Carla this doesn’t lead to change. She is stuck now. Earlier we’ve had a brief snippet of conversation between Carla and her mother. When she left her natal home it was in search of a life ‘more authentic’ than the suburban idyll she learned to despise. Alice Munro seems to be questioning what it means to lead an ‘authentic’ life. Is an authentic life one full of misery?

I don’t want to give the impression that Mrs Jamieson’s epiphany is complete whereas Carla’s is not. Each woman’s revelation is incomplete in its own way. Mrs Jamieson thinks she’s discovered something about herself, but remains blind to Carla’s real situation. She mistakenly attributes the appearance of the goat to Clark being not so bad after all — she thinks she was scared and uncomfortable mainly due to the time of night and her vulnerability, standing there in her long t-shirt. When he touches her shoulder, all is forgiven. Really, Mrs Jamieson should be more worried about Carla than she was even before. But Mrs Jamieson is probably happy to have the young woman nearby, as she has a bit of a crush on her (though she has rejected that terminology, feeling it’s not sexual).

NEW SITUATION

The reader can extrapolate that if Carla hasn’t taken the opportunity to leave Clark now, she likely never will. Especially after she learns he may have killed her goat. Notice that Carla and Clark both have names beginning with the same letter. This binds them together in our minds.

Carla no longer cleans for Mrs Jamieson, so we can expect the two women to live side by side but separately from this point forward. When written in close first person from Carla’s point of view, Mrs Jamieson is referred to by her last name, which sets her apart from Carla.

Like Annie Proulx, and most famously Joseph Conrad, Alice Munro makes use of ‘delayed decoding’, in which the reader doesn’t understand the full extent of the situation until after reading the entire story. This is why short stories need to be read twice.

[Delayed decoding serves] mainly to put the reader in the position of being an immediate witness in each step of the process whereby the semantic gap between the sensations aroused in the individual by an object or event, and their actual cause or meaning, was closed in their consciousness. This technique is based on the pretence that the reader’s understanding is limited to the consciousness of the fictional observer.

In other words, delayed decoding mirrors the way in which readers may be aware of things whose causes we have yet to discover. I believe the term ‘delayed decoding’ is another word for ‘foreshadowing’, though ‘foreshadowing’ refers to writer technique, whereas ‘delayed decoding’ focuses on the experience of the reader. I think it’s best described as ‘extreme foreshadowing’ — an entire paragraph or scene may not make sense on first reading. We’re not talking about brief mentions of guns here.

On second reading of “Runaway” it’s clear to me that Clark is abusing the animals. He neglects the boarding horses, but is taking his frustration out on the goat, who in Carla’s dream has a hurt leg. But is the dream based on fear and on reality? When we first read it, it’s just a dream. (In short stories especially, dreams are never ‘just dreams’.) We are given another clue to the abuse when the goat likes Clark at first then attaches itself to Carla, henceforth less skittish. By the time Carla wonders if Clark has killed the goat, we know it to be true.

We can also safely extrapolate that Clark will abuse Carla, and if not Carla, their future kids. That’s if Clark does not kill Carla first, as he has killed her spirit animal, the goat. For now, Carla will live on eggshells. Or as Munro writes it:

It was as if she had a murderous needle somewhere in her lungs, and by breathing carefully, she could avoid feeling it. But every once in a while she had to take a deep breath, and it was still there.

In the final scene, Munro makes use of a technique I’ve heard described as side-shadowing. In one version of the ending, Carla finds the skeleton of the dead goat and visits it as if she visits a grave.

Or perhaps not. Nothing there.

Other things could have happened. He could have chased Flora away. Or tied her in the back of the truck and driven some distance and set her loose. Taken her back to the place they’d got her from.

Another short story making use of this technique, in which the reader is given a variety of possible scenarios and invited to pick the most likely, is “The Wrysons” by John Cheever.