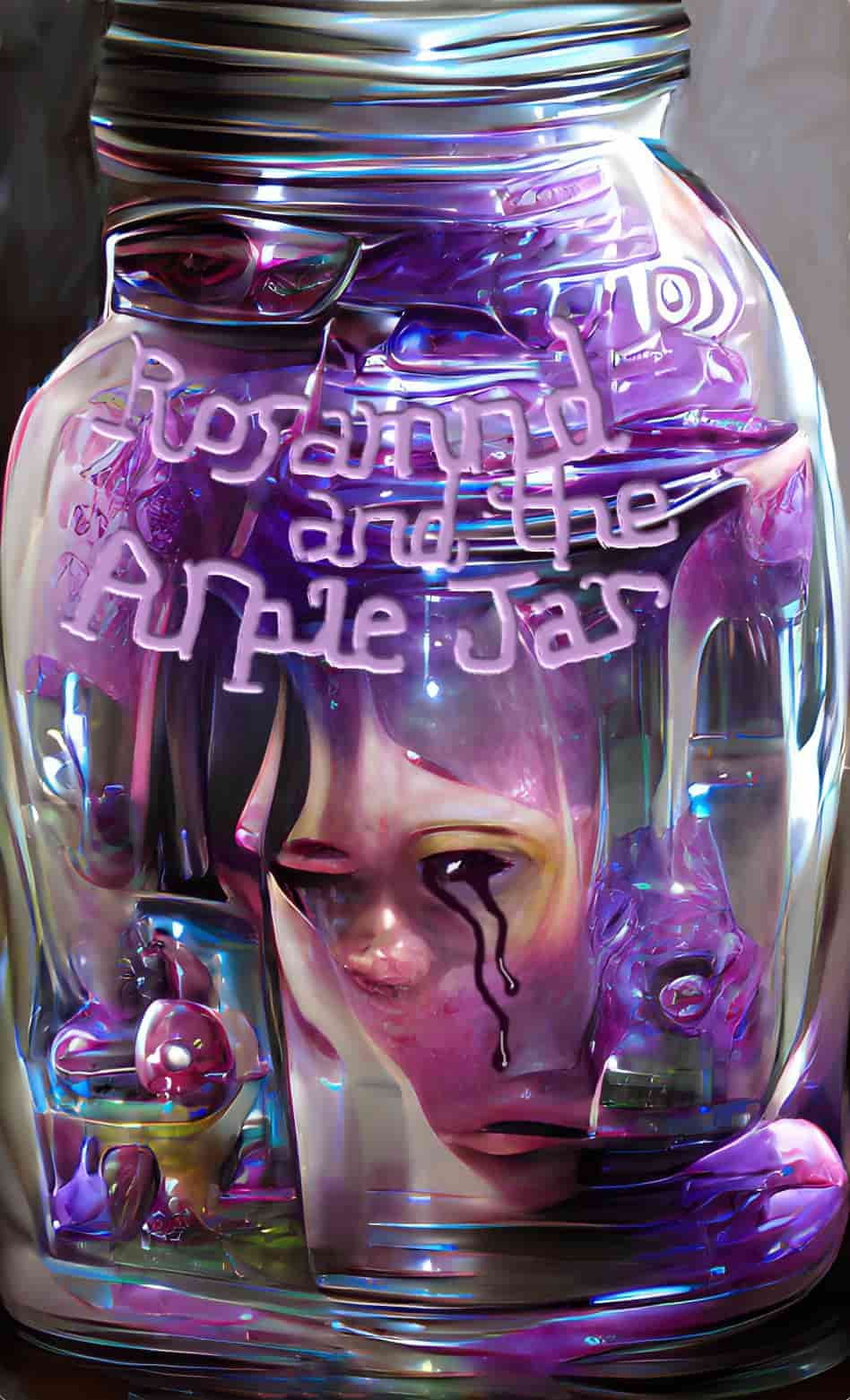

“Rosamund and the Purple Jar” is a short story for children, written by Maria Edgeworth, first published 1796. Maria Edgeworth was born in 1768 and died in 1849. She was Jane Austen’s favourite novelist and also a pioneer in children’s literature. That said, the category of ‘children’s literature’ was yet to be defined. (Children’s literature wasn’t a thing until the middle of Queen Victoria’s reign.)

Maria Edgeworth had, wait for it, twenty-one siblings. (Her father married four times.) She had much to do with the care of those siblings, and it was natural that she started writing for a child audience.

THE LONGEVITY OF CHILDREN’S AUTHOR MARIA EDGEWORTH

Contemporary children are no longer reading the work of Maria Edgeworth. By today’s standards, her stories seem didactic, though for her era, they were refreshingly non-prescriptive. Her stories were in print for a long time, right up until the 1930s. That’s a century and a half in print. Perhaps your (English speaking) grandparents or great grandparents read her work as children.

“The Purple Jar” first appeared in a 1796 edition of The Parent’s Assistant. It was published again in 1801 in Rosamond. There was no bright line between children’s books and magazines of this era. Many works were published piecemeal, in magazines, newspapers, booklets and flyers, then collected into books later.

THE WORLD WHEN THIS STORY WAS PUBLISHED

To remind myself how old this story really is, what else was going on in the world at this time?

In 1796, Horace Walpole died. (He kind of invented the ‘Gothick’ with The Castle of Otranto.) Jane Austen turned 21. Ten Presbyterian missionaries arrived in Tahiti to try and save a population a decade after Captain Cook’s arrival had totally upset the island’s equilibrium. John Adams defeated Thomas Jefferson in the U.S. presidential election. The first two white women to ever visit New Zealand had arrived only the previous year. Australia opened its first theatre in Sydney. Japan was fully isolated.

So this story is very old. Of course it’s overtly didactic by contemporary standards. But what are the messages? And have the messages themselves held fast?

SETTING OF “ROSAMUND AND THE PURPLE JAR”

This story might take place in any number of English speaking areas. Maria Edgeworth was herself an English-Irish writer. She was born in Oxfordshire England but moved to Ireland after her mother died and her father remarried. This story is set in London, where all the best things could be found in shops.

THE DOMESTIC NUCLEAR FAMILY

Most of Maria Edgeworth’s stories were domestic, taking place inside the home. This is a rare outing for a little girl character. (Of course she’s bowled over by the experience!)

The family is a nuclear family with a mother, a father, a son and a daughter. The Every (White) Family. They are neither fabulously wealthy nor poor. We learn more about Rosamund’s family life from the other Rosamund stories: They live in a comfortable, cosy home with a fireplace to warm up and a safe garden to play in. She shares her bedroom with her sister Laura.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SHOES

In this story, Rosamund will only have to wait a month for new shoes. For the standards of the day, this isn’t too bad. Many people had no shoes at all, ever. Many wore hand-me-downs. For the purposes of this story, money is not the issue. Prudence is the issue. So a not-too-rich, not-too-poor circumstance is perfect.

Conspicuously absent from Maria Edgeworth’s Rosamund stories: Toys. We might expect a seven-year-old girl to fall in love with a doll or a teddy bear, but no. She has a thing for glass. I find this adorable. I can totally imagine falling for glass products. It is therefore a massive punishment when she misses out on the opportunity to visit the Glass House. It’s almost as if the father has invented this trip and then disinvited her precisely to punish her for making the wrong choice.

In this way, the story is similar to Saki’s “The Lumber-Room.” To punish a young boy, the adult caregiver decides to take the other children to the beach just so she can leave him behind. This was acceptable parenting practice in the Victorian era.

FEMALE FINANCIAL AUTONOMY

Here’s what contemporary readers may not notice: Rosamund received pocket money — money of her very own! — in an era long, long before women were allowed their own bank accounts, let alone mortgages and credit cards. The fact that Rosamund had any say over the spending of money was forward-thinking for the time.

That said, this story is about a girl who ultimately squanders the small amount of money at her own discretion. So I’ll leave it up to you to decide whether this story advanced the feminist cause, or stymied it.

CHILDREN AS CONSUMERS

This story demonstrated an early awareness of children’s role in consumer culture. Today, marketers are fully aware of how children influence their parents’ spending, and tailor their marketing efforts accordingly. But even at the time of this story, even knowing that wives didn’t have full control of their own money, marketers assumed women had plenty of say over family purchases. Rosamund’s mother is clearly training her daughter up in sensible home economics in preparation for managing her own household.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “ROSAMUND AND THE PURPLE JAR”

SHORTCOMING

Rosamund is a naïf who has difficulty moderating her desires. She wants everything but must settle upon one thing. She has trouble accepting this. Later we witness her difficulty accepting the consequences of her choice.

Rosamund stands for all of us, because we all grapple with these cognitive biases:

- We don’t always know what’s going to make us happy until after we’ve made a decision.

- It is hard making decisions. (Decision paralysis.)

- It is hard realising we’ve made the wrong decision. (Post buyer’s regret.)

- We want everything but can only ever enjoy a portion of it in our lifetimes.

A GENDERED SHORTCOMING

Rosamund is also given a shortcoming specifically punished in girl characters: She is taken-in by the prettiness of something (guided by emotion) rather than looking at its function (guided by supposed logic).

She is so enchanted by the jar that she’ll underestimate the amount of pain caused by the hole in her shoe. She also underestimates how quickly the shoes degrade after today. Worst of all, she underestimates the extent to which her father will punish her for failing to choose the shoes.

DESIRE

Rosamund wants all the pretty things. She wants the jar. She wants to admire the jar as it sits on the mantelpiece. I guess she’d like others to admire the beautiful jar as well, otherwise she wouldn’t put it pride of place in the shared living area.

OPPONENT

The mother is the stand-in opponent for an entire moral universe in which no one can have everything. The universe forces us to choose, no matter how much money we have. By making one choice we cut off the life we could have had by taking the other path. This theme is often conveyed symbolically in stories which utilise the symbolism of crossroads. (There are no actual crossroads in this story.)

The mother is also a fairy godmother or genie-in-the-bottle archetype, granting only one wish.

PLAN

At seven years of age, Rosamund’s executive function is youthfully underdeveloped. She’s being dragged around these shops, full of carefully-positioned items, all of them designed to create a Gruen Transfer in the days before that particular set of marketing tactics even had a name.

The mother has a plan. She will let her daughter make her own decision and deal with the consequences.

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle scene contains a blood substitute in the form of purple liquid that, when drained from the jar, renders the jar transparent and ordinary.

ANAGNORISIS

For Rosamund this is a complete let-down. She realises she hasn’t examined the jar properly. If she had, she might have realised the colour belongs to the liquid, not to the glass. She realises she has made the wrong decision when Maria Edgeworth includes another painful step in the story: She has been looking forward to an outing with her father and brother, but now he refuses to take her because she is ‘slip-shod’.

Rosamund receives punishment for two main reasons: For making the impractical choice and also for not standing by her decision. “You made your bed, now lie in it.”

FAIRYTALE LINK

This is a lesson quite often doled out to girls and young women in stories. Take “The Frog Princess” as the O.G. fairytale example. The Frog Princess also chose a pretty thing (her golden ball returned to her) in exchange for her body and her life. Yet the message in almost all the versions of this disturbing fairytale is the same as presented in this one: “You made your decision, girl. Now deal with the consequences. You may never change your mind, even if you realise the entirety of the consequences of your decision become apparent only after you have made it.”

Notice the link between this message and rape culture. “You went to his flat/to the alleyway/to the pub with him. What did you think would happen next?”

The idea that one decision leads fatally into an entire raft of unintended consequences requires intense scrutiny.

The Kovacs song is a contemporary Just Desserts story, complete with the gender flip. This time a woman dishes out punishment. With Angela Carter-esque feminism, the female victim is ‘hairy on the inside’ (turns into a wolf) and murders the man who tries to harm her. Where do these violent woman revenge stories come from? This anger?

Well, there’s a very long history of “Rosamund and the Purple Jar” brand of ideology, of course. There’s a lot to make up for.

NEW SITUATION

Using Rosamund as proxy, the reader learns to examine goods properly before buying them. Readers must make a practical decision over an emotional one, and to listen to mother’s guidance when offered obliquely.

Here’s what I also took away from this story:

“Girls should be punished for wanting more beauty in their lives.” But fathers who refuse to take their daughters out on a trip to a wonderful ‘glass house’ (perhaps this one?) because she’ll embarrass him due to her poor-condition footwear receive no such judgement. People will think poorly of the father, for failing to provide his daughter with good shoes. An image-based decision if ever there was one.

In other words, men can make decisions based on appearance and their decision is considered reasonable. When girls use the same metrics to make their decisions they are considered shallow and silly and deserve punishment. In this case, Rosamund’s punishment comes both from ‘the universe’, with the consequence of a sore foot, but it also comes from the father, who shuns her.

TAKEAWAY MESSAGES

Here are the parenting ideologies Maria Edgeworth became known for:

- Let children use their own reasoning to govern themselves.

- Let children make their own decisions.

- Open children up to experiences so they learn wisdom.

- Let children suffer the consequences of their actions. It may be painful, but the long-term rewards will be worth it.

- Offer children freedom by holding back with our own adult opinions. (Ironic, given the overt didacticism of Edgeworth’s actual stories.)

- She didn’t like toys for kids. Highly coloured miniature versions of real things were all bells and whistles so far as Edgeworth was concerned. Children should learn to appreciate the ‘real’ world around them.

I don’t know about you, but these child-rearing tactics sound pretty modern to me. In fact, that last one, about the toys, could be switched out for ‘electronic devices’.

What about the messages of “Rosamund and the Purple Jar”? There’s a nasty flip-side to all of this ‘let her make her bed and lie in it’. But it’s not limited to didactic tales from the 1700s. Many contemporary girl characters in middle grade fiction are also punished for their choice of pretty accoutrements over functional objects. Storytellers attempt to offset the sexism of this by writing feisty girls. But I have already written extensively about that.

“ROSAMUND AND THE PURPLE JAR” AS ALLEGORY FOR MENSTRUATION

Some commentators read “Rosamund and the Purple Jar” as a tale about menstruation (even before the widespread use of menstrual cups).

I feel this is a stretch. Rosamund is only seven years old, living in an era where menstruation was taboo and therefore completely hidden. Menarche happened later back then. Rosamund is nowhere near puberty.

But if this story is about menstruation, what does it say, exactly? I guess it’s this: Don’t be too quick to grow into pretty ladies, little girls, because the reality of womanhood will disappoint. Womanhood is all about wearing a mask. Underneath, we’re all just ordinary. We are all debased, leaky vessels who make meaty humans, underneath those pretty clothes, those jewels, those cosmetics.

“Rosamund and the Purple Jar” as a parable about capitalist consumerism is perhaps more obvious.

RESONANCE

New Zealand social worker and poet Ursula Bethell wrote a poem called “By the River Ashley” (1950).

In that poem is the line:

(Well we understood the experience of Rosamund and her Purple Jar!)

Maria Edgeworth’s poem is a harsher story than the narrative by Ursula Bethell. Rosamund’s father rejects her because she isn’t wearing the correct shoes. In the 1950 poem, river stones no longer look wonderful when removed from water. As someone who grew up near the same river, I know exactly that feeling. The reason for Bethell’s allusion is clear. Rosamund’s jar also loses its magic.

Header painting: Rosamund and the Purple Jar exhibited 1900, by Henry Tonks