I remember the day Roald Dahl died. I was in Year 7. I remember sitting at my desk, and where that desk was positioned in the classroom, thinking about how Roald Dahl had died.

Australian author Paul Jennings describes the time he met Roald Dahl.

In Untwisted, [Jennings’ autobiography] he recounts the experience of meeting Roald Dahl after an event in the late 1980s, when Dahl was 72.

ABC News

Authors were lined up in pairs to greet him as he sat on a lush chair at the end of the room.

“The king on the throne,” is how Jennings describes him.

Lots of other important historical figures died during the 80s and 90s but I don’t remember many of those days. But everyone of a certain age remembers where they were when they heard Roald Dahl had died. Amirite?

Politically correct parents can try force feeding their kids with sugary tales but as Roald Dahl knew – what really excites a child’s appetite is the grotesque, the subversive, and the sinister.

Christopher Hitchens

Here, Hitchens uses the term ‘politically correct’ as an insult. I have found as I head into middle age that the people who use this term as an insult often wish for an earlier time where they didn’t have to watch what they said. These people are disproportionately heterosexual, able-bodied white men. (Okay, so Hitchens is technically dead now.)

Something tells me Roald Dahl would have also found the concept of ‘politically correct’ quite revolting. What would he have been like to sit next to at a dinner party, I have wondered.

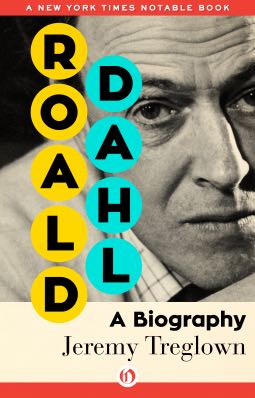

Now that The BFG has had a remake, Roald Dahl is having a bit of a comeback moment, though he never really went away. Jeremy Treglown published a biography about Roald Dahl, which you might consider skipping if you’re in love with Boy and Going Solo. Treglown offers a more ‘real’ story of Dahl.

NOTES FROM ‘ROALD DAHL’ BY JEREMY TREGLOWN

More than most people, Dahl was caught between wanting to be the ‘class clown’ and wanting a serious, respectable job.

He was mostly a businessman and his ethics are what you’d expect from a businessman. He was proud of the fact that both his father and uncle made their own fortunes in business. Eventually, Dahl did too (with his books).

When Dahl’s father died, leaving Roald’s mother a widow, he left today’s equivalent of about 3 million pounds. The fact that both he and his brother were able to become rich is partly to do with the fortune of living in Wales at a time when shipping was really taking off. It was boom time in Cardiff at this time.

On the longevity of Dahl’s work: “Not all of them will last. But the best — especially The BFG — surely will. Like folktales, they draw on deep, widespread longings and fears. They bind characters, readers, and writer into a private fantasy. They make you laugh and cry. They do all this with well-tried technical expertise, and in a way that is often a cryptogram of the life which produced them.’

Norwegians pronounce the name ‘Roald’ like ‘Roo-ahl’. The final ‘d’ is not voiced. (However, when the name Roald Dahl is said in full, it might sound like the D from Dahl is attached to the end of Roald.)

Roald himself had plenty of siblings (and half siblings) but his fictional children are lone operators. Even if they have a sibling, the sibling tends to be negligible (e.g. Matilda’s brother. Remember him?) The orphaned/lonely child is common right throughout children’s literature but in an interview, Roald didn’t seem to realise he’d done it and denied it was true of his corpus of work.

As a child, Roald was fascinated with natural things like birds, moles, butterflies and gnats. Once he ate the bulb of a buttercup to see what it tasted like. (“Frighteningly hot.”) He had excellent memories of his Norwegian summer holidays and probably came face-to-face with nature there.

Though Roald never lived in Norway, he did feel very much that he belonged there.

When home, Roald was surrounded overwhelmingly by many female relatives. His family were good cooks and good storytellers.

The children did learn to speak Norwegian.

Dahl was therefore highly influenced by Northern European folktales. Witches and ‘hags’ feature strongly in these folktales. But Dahl would also have been familiar with witches due to growing up in Wales, with the stories of the Druids.

Dahl’s story The Witches may have been particularly influenced by a woman he was scared of as a boy — an old woman who ran a sweet shop in Llandaff who he described as “a skinny old hag with a moustache on her upper lip and a mouth as sour as a green gooseberry”. [It seems Roald Dahl was particularly critical of women who didn’t gender conform in a way he personally found sexually alluring.] In Boy you might remember the scene in which Dahl and a friend put a mouse in one of the jars.

Roald Dahl admitted that his description of his private boarding school wasn’t nearly as grim as he portrayed it in Boy, and he seems to have been influenced by fiction, especially Decline and Fall by Evelyn Waugh. St Peters was actually pretty ordinary with nice, ordinary people running it.

Dahl didn’t stand out at school really. He had close friends but wasn’t especially popular or unpopular. He wrote home about football and stamp collecting.

He was pretty good at sport, or ‘games’, as they called it. He won prizes for swimming.

He was no good academically, near the bottom of 13 boys in Latin and maths. He wasn’t much better at English. But Dahl had a great memory for any story he was read or told. He also read a great many classic books independently, so I deduce that although he didn’t get good marks in school, this was due to not really caring about such things.

Dahl’s spelling was always erratic. [All of this put together has me wondering if born today, Dahl might be profiled for dyslexia or similar? Others before me have thought so, too.]

The Roald Dahl museum has a school report on which a grammar school teacher had written: “I have never met anybody who so persistently writes words meaning the exact opposite of what is intended.”

The things Dahl read as a teenager emphasised heroism and masculinity, as most classics of the day did. He was reading Kipling and Captain Maryat and Henty.

It took him a while to adapt to boarding school because he’d been the centre of attention at home, even nicknamed ‘The Apple’, due to his being the apple of his mother’s eye.

In Boy you may remember the furore about Dahl’s accusation about the Archbishop of Canterbury gleefully and sadistically flogging a small boy. Dahl got it wrong. He misremembered the man — it was the future Archbishop of Canterbury’s successor (Geoffrey Fisher had left the year before), and it wasn’t a small boy being flogged anyway. It was an 17 year old prefect who had been found in bed, possibly sexually abusing a much younger boy. There was no libel action against Dahl because Fisher had died 12 years earlier than the book came out, but the family were not happy with Dahl. Dahl did not back down. He was right in one sense — Fisher is widely remembered as “pretty crisp”, which means pretty strict, even by the standards of the day. Opinions of old boys differ.

Dahl’s stories are full of bullies. Perhaps the most telling story he wrote was a story for adults, “Galloping Foxley”.

Dahl himself has been described by others as a bully. His was a verbal more than a physical kind of sadism. He invented and persisted with cruel nicknames.

Dahl was a very keen photographer and loved to retreat to the dark room during school, partly to smoke.

Dahl never became a prefect at Repton, and he was never knighted, either. (He wanted both badly.) It’s thought that the reason he never became a prefect is probably the powers-that-be feared he would become subversive.

Though his mother wanted him to go to Oxbridge, the school made it clear this wasn’t an option. Instead, he went on a program for English public school boys as an explorer. It was a tough trip — one boy had mumps and had to go on regardless. Dahl’s boot disintegrated. But this didn’t dampen his enthusiasm for travel.

If Dahl was told to do things, he wasn’t interested. He was always trying to get round the rules.

Dahl’s typically white man attitudes made him a perfect candidate for working for Shell: “Sometimes there is a great advantage to traveling in hot countries, where niggers dwell. They will give you many valuable things.” (From his diary.)

He fit in well socially at Shell, because he’d played golf since childhood, was keen on games like poker and there was quite a bit of jovial fun in the atmosphere.

One of Dahl’s friends from around this time introduced him to crime fiction, which he loved reading for the rest of his life. (One of the last he read and recommended was Silence of the Lambs, which was a game-changer in crime fiction, even though it’s easy to forget that now.)

Dahl also loved model aeroplanes.

And women. He was especially attracted to older married women.

He didn’t earn much but didn’t have to pay board working for Shell, so spent a lot of his money gambling.

He ate a chocolate bar after lunch every day, and made an ever-expanding ball out of the silver wrappers.

In 1938 he was posted to Dar es Salaam (now Tanzania).

In old age Dahl regretted his acceptance of British Imperialism in Africa. He was a product of his time, and not a particularly critical one — more a playful one, who went with what felt easy to him. Tanzania was only comfortable because he had masses of servants.

Perhaps part of Dahl’s self-reflection came after criticism of the Oompa-Loompas in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, who were thought to represent an underclass of non-white servants. (He had to be persuaded to not depict them as Congolese Pygmy slaves.)

In 1950 Poison was published, in which Dahl satirises racism himself. So he had some understanding of racial issues but also had blindspots, or, wrote whatever would be popular without much thought to the wider cultural consequences.

At the age of 22 Dahl almost welcomed the excitement of war. His life in Tanzania was pretty uneventful for the 22 year old.

His influence as the ‘man of the family’ is clear from the fact that when Dahl urged his mother and sisters to move from Kent back to Wales, they took his advice and did so. (Dahl rightly predicted Kent would get bombed.)

He thought being in the airforce sounded more exciting than marching around in the heat, and also they’d pay for him to get his pilot’s licence, which would have been very expensive to procure otherwise. He was too tall to fit comfortably in the cockpit, but his reflexes were very good, proven already by his being good at sports such as squash.

Dahl had a near death experience, described in various writings. In the crash, his nose was pushed right into his face but he managed to avoid getting burnt alive by crawling away from the plane. His burns were only slight but his face was so swollen he couldn’t see for several weeks. He was in recovery in a hospital bed in Alexandria for two months. His nose was rebuilt. He had persistent headaches for a while after that. He was offered a berth home but really enjoyed flying, so turned the opportunity down.

Dahl’s war diaries show that as a young man he was pretty egotistical. He’s the sort of guy who came back from war with exaggerated stories of his own heroism. He was actually only in the air for five weeks total, because of his headaches and blackouts and time in hospital.

His short story “Death Of An Old Old Man“, however, is an example of one of his introspective short stories. Generally he preferred exaggeration. “They Shall Not Grow Old” is another.

Flying in the airforce had such an impact on Dahl that it was inevitable that his children’s stories would feature flight: The leaps and bounds of The BFG, Billy’s flying through flames on a swan in The Minpins, James tethering birds together in James and the Giant Peach, Mrs Twit lifted up by balloons, children being thrown by the Trunchbull in Matilda. His short story collection Over To You is a collection all about flying.

See also: The Symbolism of Flight in Children’s Literature

When he got home from the war in 1941 Dahl’s family had moved and he had trouble finding them. Almost unthinkable that this could happen these days!

After the war Dahl went to America for some back surgery and his bragging went down pretty well over there. He was popular with women, and slept with a lot of rich ones. He was tall, handsome, full of himself and wore a uniform. He’d come back early from war, so there was a dearth of young men, too.

Even before he was writing, Dahl was meeting lots of famous and wealthy people.

He also wrote in the golden era, paid a thousand dollars for his first short story. This just isn’t happening anymore, even when not adjusted for inflation.

When only 25, Walt Disney brought him to Hollywood, gave him the use of a car and put him up in the Beverly Hills Hotel. Walt was going to make a movie about the gremlins (mythical wartime elves who were said to be the cause of mechanical failures). But the general audience grew tired of war themes before the film was made. Like Mary Poppins, it was going to be part live action, part animation.

It was turned into a picturebook instead. This is the book that got Dahl into writing for children.

He enjoyed greyhound racing.

He also poached pheasants [Danny The Champion Of The World] and tickled trout. So I guess he didn’t have much of a conscience about animal cruelty.

He also liked classical music and modern painting.

He was slightly disabled after the war.

Dahl was fascinated in any species in which the female was ferocious. In one of his stories he wrote, “the female of any type is always more scheming cunning jealous and relentless than the male.”

The Twits was written using the main element of his plot in a much earlier short story called “Smoked Cheese”: a man plagued with mice disorientates them by gluing his furniture to the ceiling.

When there was a change of editor at The New Yorker, he stopped getting published there. I find it interesting that the editor changed to a woman. I feel many of Dahl’s short stories might be enjoyed more naturally by men.

He couldn’t break into the publishing market once back in England and complained to his American friends about it. The English publishing field was entirely dominated at that time by graduates of the richest private schools.

Dahl didn’t start writing ‘for’ children until he was 40. Before that he wrote a lot for adults, including for Playboy. His general tone is that of an adult addressing a child, so writing for children was a natural place to end up.

The stories he wrote in his mid thirties are almost all about manipulation: the characters’ of each other and the author’s of his reader.

Dahl has been described as a naughty eleven-year old genius. In New York, this sort of person was fashionable to have at a dinner table. They all smoked heavily and drank bourbon old-fashioneds. Dahl liked to scorn and shock, all his life.

He lost the money the father had left all his children to buy a house. Something to do with shares and stock markets.

Eventually he married the famous Patricia Neal.

He was hard to live with, as his father was. With all of those women around him I’m reminded a little of King Henry the eighth.

Patricia and Roald’s first child died age seven. Their son was hit by a vehicle as the Nanny pushed him out into traffic in his pram in New York. This affected him for life.

Roald Dahl’s children’s books originally sold far better in America, though they were set in England. This affected the setting. He made England just a bit more quaint and lively than it really is. A ‘foreigner’s England’.

Some of Dahl’s short stories demonstrate a disturbing misogyny, particularly those published in Playboy. I suppose this shouldn’t come as any surprise. There’s a particularly disturbing one about a gynaecologist who’s wife leaves him but eventually returns. He decides to take revenge on her in a way that makes me wonder about the mind of the author.

Patricia Neal had an aneurysm which left her incapacitated. She needed much rehabilitation and in her later years she even opened the Patricia Neal Rehabilitation Centre — that’s how big of a role rehabilitation played in her life. This aneurysm was widely publicised at the time, and there was much sympathy for Patricia as she was well liked. Perhaps partly in sympathy, Roald was offered a screenwriter’s job for a James Bond movie. He considered this much beneath him. What he really wanted to do was produce another solid book of short stories, as he considered himself a literary fellow and looked down on screenwriters. However, he took the job, and for this work he was paid far more than Patricia Neal herself had ever been paid. Such is sexism in Hollywood.

But was he really all that good as a writer? As a plotter he was very good. But he could sometimes get lazy in his writing. A guy called Phelps said of some of Dahl’s work, “There is only the simplest generic characterisation—the Priggish Professor, the Mousy Parson, the Grouchy Millionaire.” He compared Dahl’s use of superlatives to those of a fairytale: “An antique is not merely valuable, it is a Venus de Milo of the furniture world; a certain new food is not only delicious, it is worth five hundred an ounce.” Dahl did always fancy himself one of the best writers out there, and certainly one of the best writers for children. He was quite vocal about how much trash was out there, and was proud that he would spend more than half a year on a single piece of work, refining it studiously.

Roald Dahl was published first by Alfred Knopf. His children’s book editor was a woman called Virginie Fowler and she wasn’t an unreserved fan of Dahl’s. She didn’t like work which had one eye on the adult co-reader, but Dahl disagreed — he thought that if children’s books did not have a dual audience then adults wouldn’t read to their kids as much, so he considered this a good thing. In this regard, Dahl was ahead of his time, because the bestselling children’s books of today tend to be enjoyed at a dual level.

Fowler did very much like James and the Giant Peach: “If this doesn’t become a little classic, I can only say that I think you will not have been dealt with justly.”

I think Dahl might have had sociopathic tendencies, because I’m reminded of an interview with a psychologist whose own father was a sociopath. This guy used to do tricks such as standing up in a crowded restaurant and making a speech, giving everyone the mistaken impression that they had interrupted a wedding. Dahl did this sort of thing too. He used to buy very expensive wine and drink the lot himself. Then he’d fill bottles up with the cheapest wine he could find, and serve it up to his ‘unwitting and politely admiring guests’. He loved to diminish and demean people in this way. One acquaintance of his said “He was detached from [these tricks]. He did things sometimes almost like a scientist.” That sounds very much like a sociopath to me.

People who worked with Dahl thought he was most similar to his character Willy Wonka.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory seems racist now, but at the time no one in the critical establishment seemed to notice. This is not something that was at the forefront of white people’s minds back then.

Dahl seemed a lot happier in his second marriage.

He grew crankier and more crotchety as he grew older, and alienated publishers. The ones who managed to work with him were skilled at dealing with difficult people. Eventually, though, even the kid-glove specialist Stephen Roxburgh, who edited Dahl’s most successful children’s novels, managed to get him off-side.

Stephen Roxburgh remains unnamed and largely anonymous, but this guy had a very large part to play in making The BFG, The Witches and Matilda into the great works they are today.

Roald Dahl spent his entire life smoking and eating lots of chocolate; he was in pretty poor health for the last few decades of his life. His cranky outbursts seemed to often coincide with his perhaps being in pain.

He’s buried near his property at Great Missenden. This is a village in Buckinghamshire, where there is also The Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre. This opened in 2005, 15 years after his death.

CONCLUSION

I would not like to have been seated next to Dahl at any dinner party. I’m glad he was not my father or my teacher or had anything to do with my childhood in real life. However, Dahl had a huge part in my life as a child, and it took me some time to erase the idea that fat kids are somehow morally deficient, and that only children are spoilt brats.

Roald Dahl was a bit of a celebrity even without him being a writer. I’d thought he was famous due to his writing, but I get the feeling from this biography that Roald Dahl was always going to find his place among the celebrity class, regardless of whether or not he’d ever achieved great success with his writing.

I find myself more and more interested in Patricia Neal. What on earth did she see in him, especially since he deliberately snubbed her at the dinner party where they met, and especially since she was a woman with an independent income who didn’t seem to put up with his misogyny. Yet in the end, he left her, after her series of strokes which left her incapacitated.

RELATED

Wicked And Delicious: Devouring Roald Dahl from NPR

The tale of the unexpected decline of Roald Dahl from The Independent

Roald Dahl’s Writing Hut, which is now a kind of museum.

Felicity Dahl talks about her husband.

The Filthiest Joke Ever Hidden in a Children’s Movie from Cracked

For a very long time now I have stated in my bio’ that my writing is inspired by the adult short stories written by Roald Dahl. Roald Dahl wrote four books of short stories for adults — Over to You (1946), Someone Like You (1954), Kiss Kiss (1960) and Switch Bitch (1974). Recently, I decided to read the entire lot (and eight additional previously unanthologised short stories by Dahl) in one go. This was the first time I had read them in thirty-five years and I admit I was surprised. I was surprised at how dated the stories were. I was surprised that women’s and men’s roles were portrayed in such a stereotyped manner. The men worked and the women stayed at home. The men came home after a day at the office, sat in their armchair, sloshed down whiskey, read the newspaper, and waited while the women slaved over stoves and brought the blokes their tucker. Everyone smoked. Everyone drank, excessively (and played Bridge). Over a span of forty years from 1946-1986 the stories and their settings changed little. Women occasionally got ‘revenge’ on their inadequate husbands but there was nary a feeling of equality between the sexes.

David Vernon, editor at Stringybark