Alien is a 1979 film directed by Ridley Scott. The story was created by Ronald Shusett, also known for Total Recall. The screenplay is by Dan O’Bannon, also known for The Return of the Living Dead.

Ridley Scott is an interesting case, because he also directed one of my favourite films of all time, Thelma & Louise, which is… very different. (Or is it?)

More than any other ALIEN movie, David Fincher’s ALIEN 3 is aware of Ripley’s existence as a woman, and the unique and universal horrors that come with the territory of inhabiting a woman’s body.

Women, Aliens, and Dangerous Things: Female Bodies in Alien 3 by Sarah Welch-Larson

What story function do aliens play?

Many commentators have said that aliens in modern stories equal the fairies of yesteryear: Aliens channel our biggest fears and desires. If an actual alien watched one of Earth’s alien films, they would also have excellent insight into our beliefs and disbeliefs.

PARATEXT

Logline:

The crew of a commercial spacecraft encounter a deadly lifeform after investigating an unknown transmission.

Forget the logline. Alien has one of the best taglines in the history of movies:

In space no one can hear you scream.

Alien was released two years after the first Star Wars movie, and I wonder if that ‘There’s no sound in space, actually’ tagline came as a response to Star Wars superfan pedantry. Star Wars, (in)famously, features myriad sound effects to accompany its outer space dogfight scenes. Fans of mimesis who glossed over other improbabilities were saying, “But space is a vacuum! There’s no sound in space” This hollering even gave rise to theories about how physics works in the Star Wars universe, including how sound might work. It tires me.

SETTING OF ALIEN

PERIOD

The distant future.

DURATION

a story’s length through time. Maybe it takes place over a year, cycling through each season. Maybe it takes place over 24 hours.

LOCATION

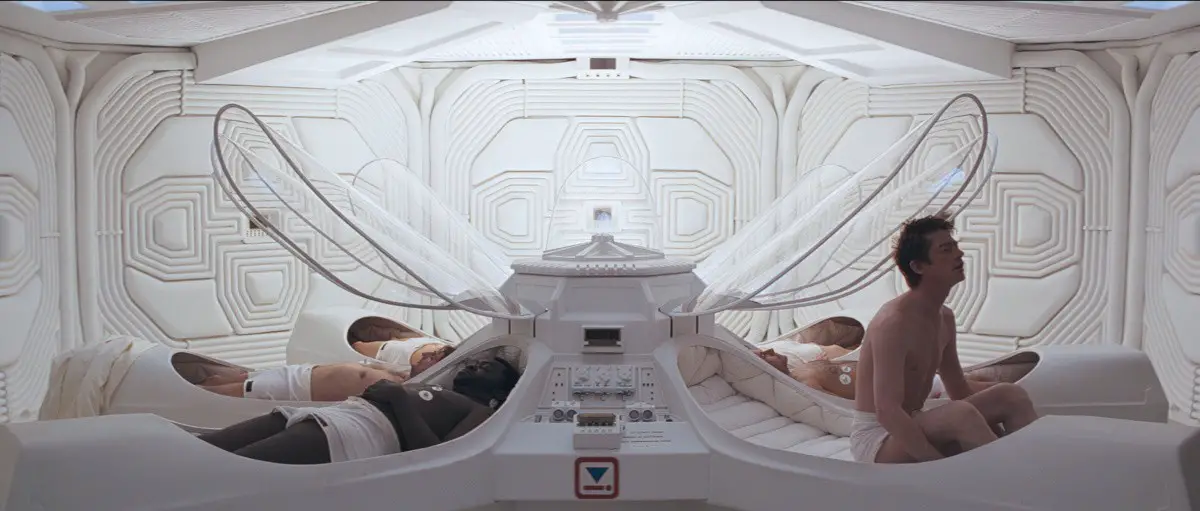

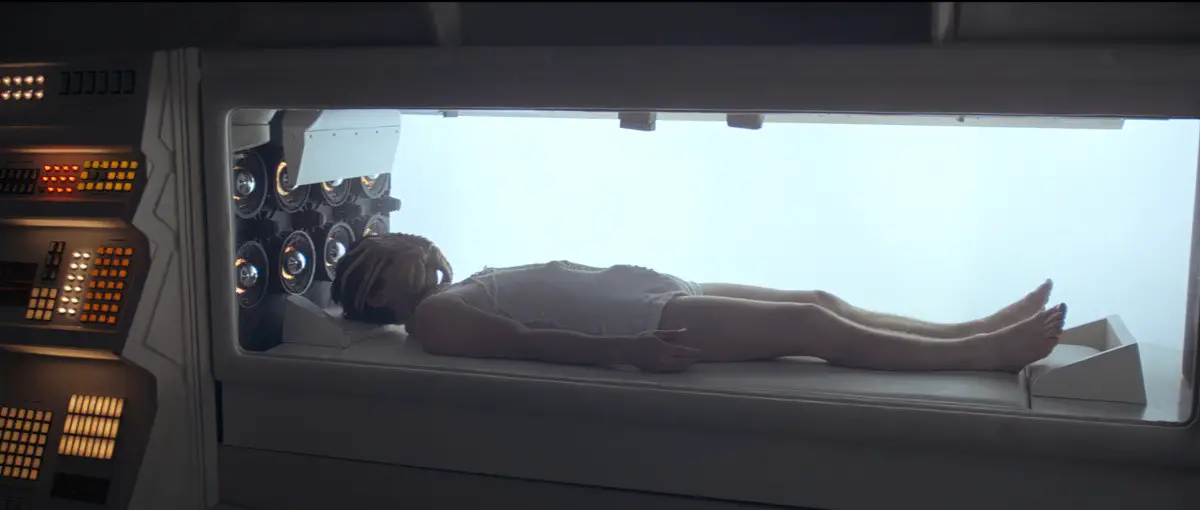

Outer space. A long way from Earth. We know this, because the characters have frozen themselves.

ARENA

Audiences have no real concept of the vastness of space, so the arena doesn’t require further specification.

MANMADE SPACES

The space ship is manmade, with technology that is still nowhere near existing, even in 2022.

NATURAL SETTINGS

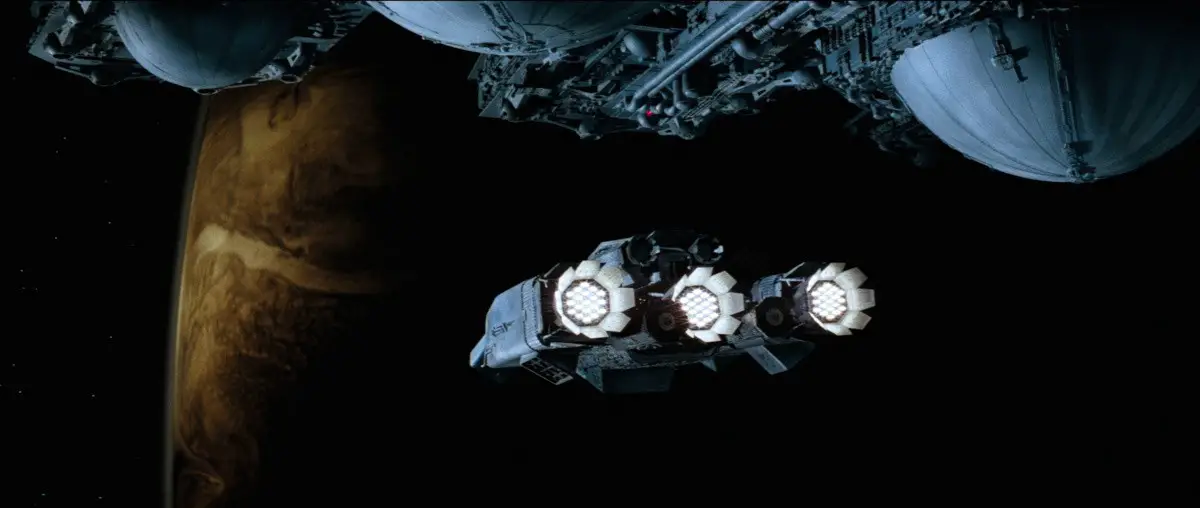

Planets. One of the crew members refers to a planet pejoratively as a ‘ball’, which is wonderful. In any workplace, workers create their own ‘familects’. Sharing the same language helps us work better together. It is completely believable that people sent into space would create their own shared dialect like this.

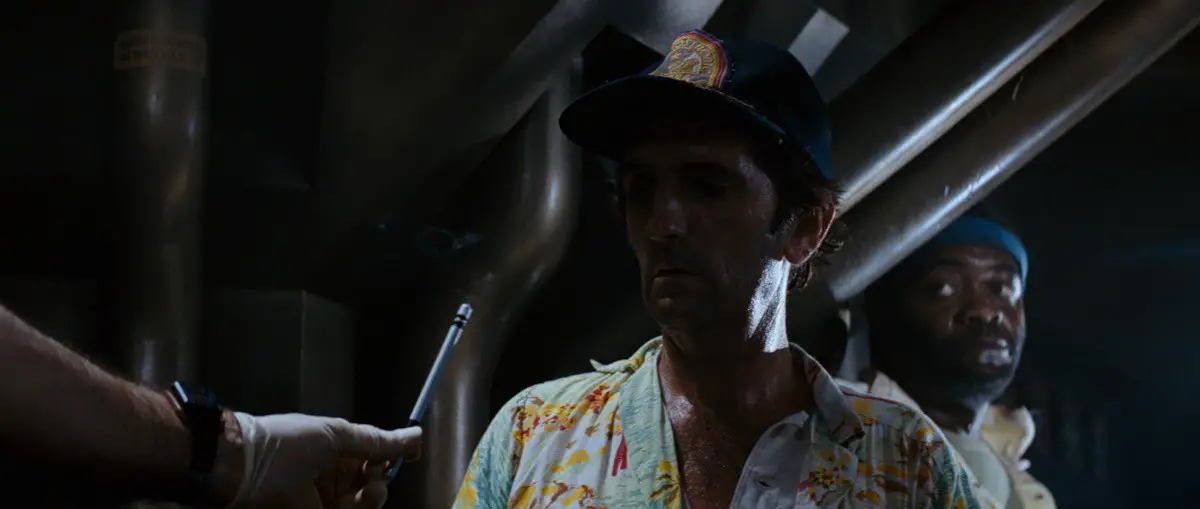

To call a planet a ‘ball’ is also to minimise it. Not only does workplace specific slang terminology create verisimilitude of a workplace, it also shows the audience that these people have ‘seen it all before’. They go to new planets, collect mineral resources, bring it back to Earth. The Black guy is constantly chewing gum or eating. Others are constantly smoking. In error they think there’s nothing to see here. They disregard protocol. They will, of course, pay for this error.

Much of the film feels like it is set underwater. Basically, a story set in space equals a story set underwater. Both are ‘alien’ environments, unsuited to human life. Characters must wear costumes which support life. (Generally this is a bubble over the head.) Without gravity, characters float in space as they would underwater.

Although artists depicting underwater scenes use a wide variety of hues (other than blue), the archetypal ‘underwater colour’ is blue. Hence, cinematographers generally make an underwater world which is not actually underwater look blue.

When adults enter bodies of water in stories, this frequently evokes the symbolism around motherhood and birth. Water as amniotic fluid. Anagnorisis as rebirth, etcetera. So it is here. It’s not subtle; the ship is literally called Mother.

Keeping with the mother theme, the alien life form is about to utilise human bodies as hosts for its own incubation and procreation purposes.

Then there’s the insect symbolism. Oh boy. Brilliantly, Alien interweaves a 1970s concept of computers with the chirruping of insects. My earliest interactions with a computer happened on an Amstrad. It was four years older than this one below. (That creamy, fawn colour is straight out of Alien, right?) The MIDI muzak that came out of these machines was quite something. As kids we thought it was great. The incessant chirruping meant ‘games’. But sit me down and make me play half an hour of Space Invaders today? I’d go mad. Alien utilises that classic MIDI sound and incorporates it into the soundscape, alongside extradiegetic orchestral music we associate with mid-century films.

There’s a definite ‘insectoid’ feel to the MIDI sounds of yesteryear. The Alien itself is inspired by Earth insects. For horror inspo, go no further than a David Attenborough insect documentary. Insects which lay their eggs inside other creatures exist.

But let’s go even further with the insect symbol web, the imagistic pattern, or whatever you prefer to call it. The space ship itself is filled with creepy corridors.

The Gothic novelists utilised these creepy corridors in their Gothic mansions. Go further back, the Ancient Greeks created a symbolic labyrinth with a Minotaur at its centre. But we can get even more primal than that. These corridors are intestinal. What collocates with ‘intestinal’? Worms. At any given time, we all have worms. It’s only when the parasitic loading gets out of balance, or we get a particularly nasty worm that we now ‘Have Worms’. We always have worms. We have co-evolved with them, and actually, we need them. Not enough worms? This opens us up to inflammatory bowel disease and Chrohn’s. A womb is a sterile place. Yet eventually all of us must enter the dirty world, away from the sterility of the Mother ship, and find our own way to co-exist with the dirty and often outright disgusting reality that is life.

Like any good space story, Alien is not a hypothetical story concerning outer space, but is rather a story of familiar Earth-bound commensality.

WEATHER

The space ship is a controlled environment. However, the eggs are incubated in a place which reminds the human visitors of ‘the tropics’. It is hot and humid. This foreshadows the reality that we’re about to encounter biological life, in which incubation works as it does for reptiles and birds here on Earth.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

Amazingly, for a film released in 1979, the main thing that dates the story is the CRT monitors and the 8 bit font on the screens. But we can almost handwave that one away by imagining a corporation which doesn’t spend money updating its equipment.

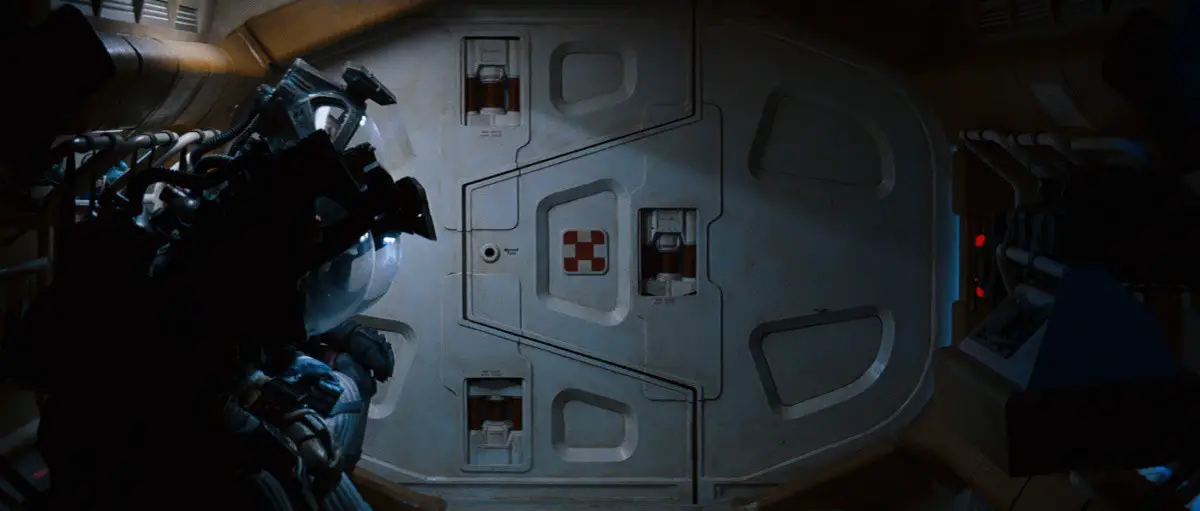

Then there are the walls of toggle switches, which have gone the way of the dodo. Ripley has memorised exactly what each (unlabelled) switch does, and knows exactly which combination to turn on and off. These toggle switches cater to the 1979 audience conceptualisation of computers, which work in binary. When Ripley communicates with Mother (the ship) she is communicating in binary by switching those toggle switches on or off.

Ripley’s memorisation of this rote task is an interesting insight into 1970s skillsets. Much is required of contemporary workers, but memorising long strings of binary is not one of them. This change in brainwork applies to many, many jobs: Checkout operators are no longer required to memorise prices, for instance. Computers have taken on these basic memorisation tasks for us.

So it’s not really the tech itself which dates this story, but the way the humans interact with it. Added to that, it was inconceivable in 1979 that people would no longer be permitted to smoke at work. This is the most jarringly 1970s thing to me.

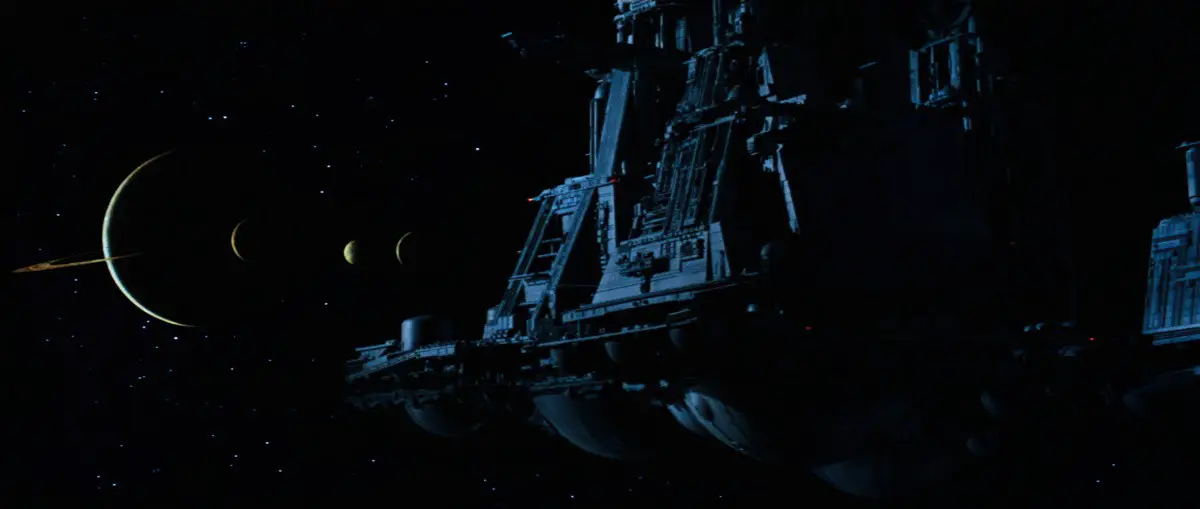

Back to the technology of Mother, this entire space ship feels clunky. (It’s sure not aerodynamic.)

To enter this space is to descend upon that old shopping mall at the struggling end of town, which you know felt glamorous once, but which has not been updated in decades.

The space ship is basically an Earth-bound sea ship, only in space. There’s even a cat. Why would they take a cat into space? Although Ripley has bonded with this cat, I put it to you that the cat’s main job is to do the work of a mouser. Without a mouser, they’re all in trouble. Perhaps my mind is going there because, here in in Australia, we endure a massive mouse problem whenever there’s not a drought. On board the space ship of Alien, the entire crew will be put to sleep for months on end. Here’s what you don’t want: one pregnant stowaway mouse. By the time you wake up, the entire ship is covered in mice, Pied Piper style. That’s if you even wake up. Mice love to chew through electrical cords. Once they’ve chewed through your entire food supply, they’d definitely get started on Mother’s cords, until Mother is nothing but a dead vessel floating through space forever, with slowly thawing human bodies adding to the stench of a carpet of dead mice. With nobody there to smell them.

But that would be an entirely different sort of movie.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

The conflict is pretty basic. We have a sociopathic alien life form who doesn’t care about the humanity of its invaders.

Any story like this requires some conflict between the ‘family’ (or in this case the crew members.)

Alien emulates workmate relationships really well, I feel. These people feel like workmates. They don’t feel like family, they don’t feel like friends. They’re here to do a job. I also appreciate that there’s no romantic subplot. With two women on board and five men, okay, four men and one ‘man’, this film could have taken a completely different direction. There’s no sexual tension either, which is refreshing.

That said, the script requires that Sigourney Weaver undresses near the end, in an oft-seen trope in which a woman gets down to her underwear before realising there’s a predator ‘in the house’. The men were wearing nappies, basically, in line with the mothering symbolism.

So why the hell isn’t Weaver wearing nappies? Doesn’t she get to be a baby, too? Nope. Weaver’s character was everyone’s ship mother, and before a woman gets to be a mother, she will be seen as attractive, or at least as someone to overpower. Weaver’s plumber’s-crack Brazilian briefs take us out of the story by appealing to voyeurism. In Hollywood, no buff female body remains clothed without disappointing audience expectations.

The space-underwear scene was replicated much later in Gravity, when Sandra Bullock is also required to strip down to her smalls. (Gravity is a granddaughter of Alien, but with a strong Christian ethos running through.)

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

I appreciate that the characters arrive on stage in statu nascendi (without back story). Contrast with Gravity, in which Sandra Bullock’s character has that old chestnut given to female characters who are doing important work: She has lost a child. I swear, mothers who have lost their children are as common in Hollywood as orphans in American children’s literature. Why does this trope annoy me so much? Because it feels to me like, no matter what else a woman does, if she is not a mother this must be lampshaded somehow, because women are naturally mothers. So the only way to make a childfree woman relatable is to make her a woman who made the ‘correct’ choice to become a mother, but who tragically lost a child, through no fault of her own.

In this respect, Alien borrows flat characterisation from the long tradition of cosmic horror.

Of course, backstory is never interesting unless it’s ironic, meaning, it’s not what we’d expect. If we give it any thought at all, we can deduce these people live for their work. They wouldn’t have their own families. This would be impossible, since everyone they knew on Earth would have already died, by dint of living a normal human lifespan on Earth time, without ever being frozen. These characters are like the time-unbound characters out of Isaac Asimov’s The End Of Eternity.

Anyway, back story isn’t useful when you hope the audience will psychologically board the space ship and put themselves in the position of the characters. These characters are the Every Person by design.

In the specific context of this film, these people are workmates, and how much do we know about our workmates anyway? Sometimes not very much. On top of that, the characters will be picked off one by one. We know that as soon as the first guy gets creatured right in the face. This is a horror, not a tragedy. The audience isn’t supposed to feel for the people who die.

However, we are supposed to root for Ripley. Let’s take a closer look at how the scriptwriters and actors helped the audience to:

- Understand that we’re supposed to like and root for Ripley

- Understand that everyone else is expendable, don’t even worry about it.

STORY STRUCTURE OF ALIEN

Watching Alien today, this story feels like a run-of-the-mill Final Girl plot. We must respect the storytelling and remember, Alien was ground-breaking in its day. Notably, Alien offered men the story of sexual assault. For the first time on screen, men experienced the visceral horror of having their bodies invaded against their will, filled with another being, and were forced to birth it.

Men and boys experience sexual assault at higher rates than is depicted on screen. Such is the taboo.

The Australian Child Maltreatment Survey of 8500 Australians published in the Medical Journal of Australia in April found one in five boys and one in three girls – or 28.5 per cent overall – experienced sexual abuse before the age of 18. This included cases where the offender was also underage.

The shocking number of Australian men sexually attracted to children and teens Caitlin Fitzsimmons November 20, 2023

SHORTCOMING

Ripley is one of the first Strong Female Characters (TM) to appear on the big screen. How do we know to root for her?

- She is always calm and collected. Unfortunately for feminism, a contrastive ‘hysterical’ woman has been written into the script. Hollywood requires someone to cry and scream whenever shit goes down, and that soundtrack comes from the weaker woman, who looks constantly on the verge of crying. I mean, I don’t blame her. I wouldn’t be entirely happy either. Since audiences will compare like with like (men against men, women against women), there’s more than one token woman for a reason.

- The actor who plays Ripley is good looking. An evergreen Hollywood shortcut to empathy, predicated upon the audience cognitive bias of lookism.

- Ripley cares for her crew. She is also good at her job, which I guess is to do with compliance. She has read the manual and knows that hand-face guy isn’t meant to come back onto the ship for at least 24 hours, in case he kills them all. Ripley predicts this will happen and it turns out she’s right. We like people who are right.

- She tells some guys (who deserve it) to fuck off. Well, they don’t actually hear her. That’d be a bridge too far for a 1970s audience. But we know she thinks it, and an audience can broadly relate to the impulse.

Since Ripley has no backstory, she doesn’t have any interesting ghost or flaw or whatever, and she doesn’t really treat anyone else badly. In fact, she’ll even (literally) Save The Cat. In short, she’s not an especially interesting character. That’s okay, because the alien and the high-production values feel interesting and novel to a 1979 audience.

DESIRE

Ripley would like to get everyone back to Earth safely.

OPPONENT

THE CORPORATION

The corporation who owns Mother has written some code into the ship which prioritises scientific progress over individual human lives. I’m sure we could go deep into the ethics of this, and relate it back to reproductive rights. I mean, that’s turned out to be a freakin evergreen topic.

Basically, the seven crew members of this ship are required to investigate potential extra-terrestrial life forms, otherwise they don’t get paid. Ah, worker rights. Another evergreen topic. (Are these workers in a union? Are unions even a thing in the distant future?)

THE ALIEN

So, the corporation is a relatable opponent. Moving on to the science fiction opponent. The Alien. When we first meet this thing, it is an egg. Not scary, yet.

When this guy taps the egg, he is Pandora, opening Pandora’s Box, unleashing evil into the world. Like Pandora, he is obliged to. If you’ve only ever read bowdlerised versions of Pandora and her box, you may feel that Pandora was an idiot. In the much earlier Greek mythology, Pandora was used as a tool, just as this guy is used as a tool (for the corporation). Long story short, Pandora is used to trick the hapless Epithemeus as the box, actually the jar, is used to trick him. Important point: Pandora was tricked into unleashing evil into the world… though she still copped the blame, of course.

When we next see the Alien, it is highly reminiscent of a human hand and it has glommed onto the guy’s face. Later, after Ripley expels the thing from the smaller space ship out into the void, it refuses to die (like a typical horror villain) and it’s definitely in the shape of a human. I am told by someone who is a big Alien fan that in later movies, it becomes clear that the alien takes on some of the genes of its host. If it looks like a hand right now, I’m guessing that’s because the guy first tapped it with his own human hand?

More to the point, the human hand is a wonderfully horrific thing.

EACH OTHER

It’s fine, it still works, just, I wouldn’t chew the end, okay?

Crew members each have their own ideas about what should be done. They never learn to come together as one. The alien picks them off, independently from each other. This is their punishment. Hollywood is ultimately conservative. Always follow protocols, it is telling us. “Safety guides exist for your own protection.” This message is (blessedly) muddied a little by the fact that had they refused to follow corporate orders and investigate the lifeform in the first instance, they’d have avoided the whole sorry mess. The more complicated message, then, is this: If you’re going to break rules, break them big.

PLAN

Most of the plan has been carried out before the film begins. The crew have collected valuable resources from a distant planet. Now they’re returning to Earth with the goods. But their plan has been interrupted. It takes a while for them (and us) to understand that they are in fact still ten months away from Earth. This upsets some of them. The Black guy is especially incensed. They need to be paid extra for this, dammit.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

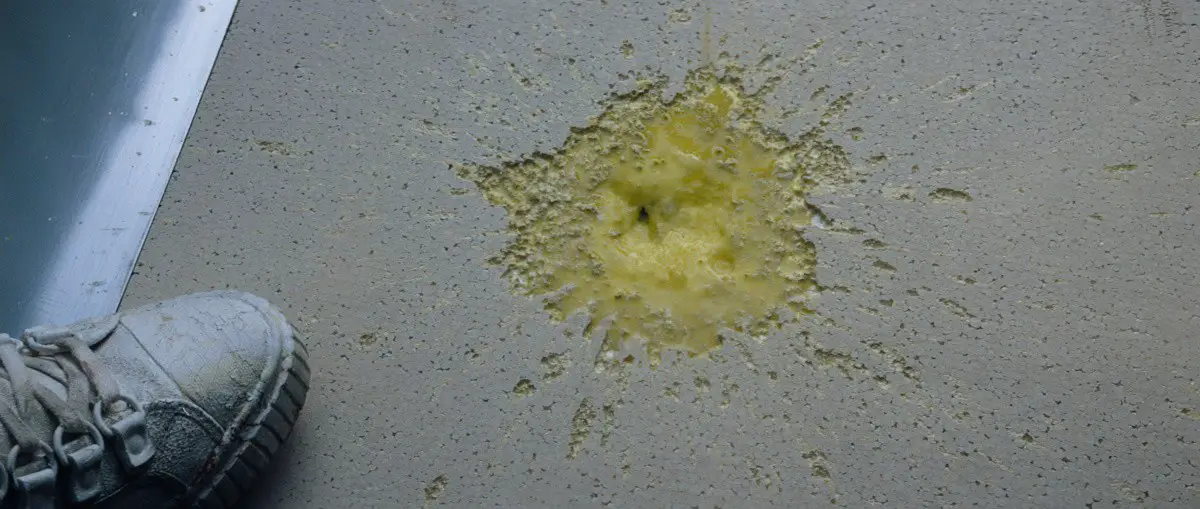

The alien can’t be killed. It is the ultimate lifeform. It has acid instead of blood, can adapt and thrive in brand new environments, it rapidly gets bigger in size, it has TWO SETS OF TEETH (Frank Sinatra voice: That’s a moray).

The majority of the film involves the villain (alien) on ship, and the fight to get rid of it.

Another film with a very similar plot: Dead Calm (1989). Dead Calm is based on a 1963 novel by Charles Williams. There’s nothing new about this plot. It’s all in the execution. Despite being made 10 years later, Dead Calm is a much less woman friendly story than Alien.

A run-of-the-mill plot will require some interesting reveals.

The big reveal in this story, apart from the unfolding terror of the alien: One of the crew members turns out to be an android.

Connecting to the whole mother symbolism thing, he is filled with a white synthetic fluid which puts us in mind of milk. The creators of Westworld utilised this imagery (and also this reveal) decades later.

See: Milk In Westworld at the Fandom Wiki

ANAGNORISIS

Ripley eventually understands that she’s the only one left alive, and barely at that, so she will have to blow up the entire ship. (She does save the cat, in line with her empathetic characterisation.)

But does Ripley learn anything about herself? Not really. She’s a flat character.

The audience learns that this creature won’t quit. Humans aren’t suited to existing in space, and that there could be life out there, and horrors we cannot begin to imagine.

NEW SITUATION

Ripley has saved her own life, for now. This is just as well, because she has to appear in subsequent movies, too.

RESONANCE

Although the alien creature is clearly bound by the limitations of animatronics, the terrifying character design remains terrifying. A much more recent horror film such as The Ritual (2017) features a horrific creature with similarities to the alien of the Alien franchise, notably in the creepiness of its hands.

FURTHER READING

The final girl trope actually began with a scholar named Carol Clover and she came up with the term. She puts forth that Laurie [Strode], the Jamie Lee Curtis character from Halloween, is the quintessential Final Girl. […]

The Final Girl has a sort of asexuality or tomboyishness. Her sexuality isn’t alert. She isn’t committing the sin of being a sexual person.

Or she’s a virgin. Even if she does come across as very traditionally pretty or feminine she is not actively exploring her sexuality with anybody. But also, there’s a fungibility of gender happening. What Clover proposes: There’s actually a switching of gender as the movie goes on. Laurie is feminine, sort of tomboyish, so she has the potentiality to become more masculine as the movie goes on. And she survives and starts to fight back and stab back and hurt back in ways that push back the monster. The knife is a phallic symbol. The monster can now be penetrated.

One of the reasons this happens is because for so long the ideal viewer of horror was white heterosexual males. Because you have this white male viewer, the protagonist has to be sort of tomboyish. The hero cannot be classically feminine and classically sexualised because she is representing this white male viewer. So she becomes more masculinised and begins to align with the view of the ideal viewer. So she can’t be this pretty girl. As the protagonist, she’s the person you’re supposed to meld with and identity with.

So Clover talks about gender in really interesting ways in horror. Revolutionary.

The purpose the Final Girl fulfils is this entry into the cathartic potentiality of horror. [This is] a sort of controlled trauma exposure. We openly go into it. Horror reflects our cultural anxieties. So horror, in this anxiety, also has us face really uncomfortable truths. One of the uncomfortable truths horror plays upon is the ever-present danger to women because they are women.

Blackness is consistently associated with masculinity. And so Black women aren’t constructed as the consistent potential victim that white womanhood is constructed as, when you racialize the final girl as Black. Where do you have to go when a Black woman starts off as masculinised? You can’t become more masculinised, right?

Selena from 28 Days Later [is the best example of a Final Girl who defies those expectations], no questions about it. She kills a man with a machete, no hesitation. She sees that he’s infected. There’s no, “Oh, should I?” No “whoops!” She’s hacking away like she’s hacking at a tree for wood. You’ve gotta love a woman who’s so determined and is decisive.

She starts off tomboyish in very androgynous dress. All you know is that she’s human the first time we see her, and not infected. As the movie progresses she actually moves to the other side of the spectrum and becomes more feminised. But she becomes more feminised in a way that isn’t coded as weak. In the end she’s in a ballgown and she has one of the soldiers threatening to kill her. At the end of the world what do you need? Women and girls to repopulate the world, right? So she [and another girl called Hannah] have been kidnapped. There’s the ever-present danger of being raped. She’s fighting for Hannah’s life, Hannah’s fighting for their lives and Jim is coming to rescue them both. So it’s no longer the individual fighting to survive. It’s the group working together, pushing forth this idea that the community itself must survive, it’s not about the individual.

That’s very different from the idea that there’s one Final Girl to kill them all.

That’s something I particularly like about 28 Days Later.

The new “final girl” in horror; plus, who’s afraid of a horny hag? It’s Been a Minute podcast

Tuesday 24 October 2023, Dr. Kinitra Brooks

They then discuss another Black Final Girl movie, Barbarian (Danny Boyle). The main character is the sole survivor. She is the one who kills the monster and she is the one who is triumphant in the end. However, her actions don’t ring true to the Black women speaking. If they turned up at night to an Airbnb and got bad vibes, they’d be taking the next plane out of there, right back home. Instead, the Black woman character makes an entire series of unrealistic decisions, each decision putting her in more and more danger. The writers didn’t seem to understand that Black women navigate the world completely differently from white men, based on a very real experience of increased vulnerability. The problem is, Black women aren’t considered potential victims. That’s the construct.

Also, Black women are constructed as natural caregivers, so of course she makes the decisions to do as she’s invited to do by the white man. Note, too, that the actress of Barbarian has lighter skin and softer hair, to allow a white audience to identify with her.

(Sub)text podcast episode: Sex and Tech in “Alien” by Ridley Scott

Editor Roundtable: Alien Show Notes, Story Grid podcast

ALIEN WORLDS

Author interview at the New Books Network

Life on Earth depends on the busy activities of insects, but global populations of these teeming creatures are currently under threat, with grave consequences for us all. Steve Nicholls’ book Alien Worlds: How Insects Conquered the Earth, and Why Their Fate Will Determine Our Future (Princeton UP, 2023) presents insects and other arthropods as you have never seen them before, explaining how they conquered the planet and why there are so many of them, and shedding light on the evolutionary marvels that enabled them to thrive. Blending glorious imagery with entertaining and informative science writing, this book takes you inside the hidden realm of insects and reveals why their fate carries profound implications for our own.

Alien Worlds: How Insects Conquered the Earth, and Why Their Fate Will Determine Our Future

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS 2023