Rich as Stink is a short story by Canadian writer Alice Munro included in the 1998 collection The Love Of A Good Woman.

Gaslighting, parentification, spousification, self-objectification, coercive control… People living in 1974 did not have ready access to the language of psychology and found it difficult to describe emotionally abusive relationships, let alone talk about the shame. Likewise, there wasn’t the language to describe that disorienting transition from girlhood to womanhood.

THE LOVE OF A GOOD WOMAN (1998)

- “The Love Of A Good Woman” — a story revolving around a crime but not a crime story. Reminiscent of Stand By Me. Also in the December 23, 1996 edition of The New Yorker.

- “Jakarta” — not actually set in Jakarta. A story of an old woman whose husband went missing, and also about the so-called ‘free love’ of the 1960s, which afforded far more freedom to men.

- “Cortes Island” — a symbolic island standing in for the psychology of newly wed isolation. Also in the October 12, 1998 edition of The New Yorker.

- “Save The Reaper” — a re-visioning of Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard To Find”. Also in the June 22, 1998 edition of The New Yorker.

- “The Children Stay” — What did divorce look and feel like when divorce was brand new? Also in the December 22, 1997 edition of The New Yorker.

- “Rich As Stink” — Focuses on an adolescent girl. Some commentators call her ‘precocious’ but I think she is a typical 11-year-old.

- “Before the Change” also in the August 24, 1998 edition of The New Yorker

- “My Mother’s Dream” — Critics don’t love this one, but I do. I read this short story as a commentary on how it takes a village to raise a child, and when any given mother doesn’t measure up as parent, other women can step in. Together, caregivers can band together to create a ‘whole’, and bring up a perfectly rounded and cared-for child, but alone? No. And we shouldn’t expect mothers to be perfect.

But Munro must have studied all this in detail, because she wrote about these things with deep insight. As Esther Perel has said on her relationships podcast Where Should We Begin, one big job of being in a relationship is working out the power dynamics. Oftentimes, one person is afraid of losing the other; the other person is afraid of losing themselves. This story isn’t about that exactly, but power and control within relationships is a theme that spans Munro’s work, and “Rich As Stink” is yet another permutation of power relinquished, power gained. Sometimes, when power balance goes very, very wrong, we end up with a coercively controlling dynamic. Munro showed interest in this dynamic from her early work, starting perhaps with Queenie, the classic delineation of a coercively controlling man. Partly for this reason, I code Derek as a coercively controlling man.

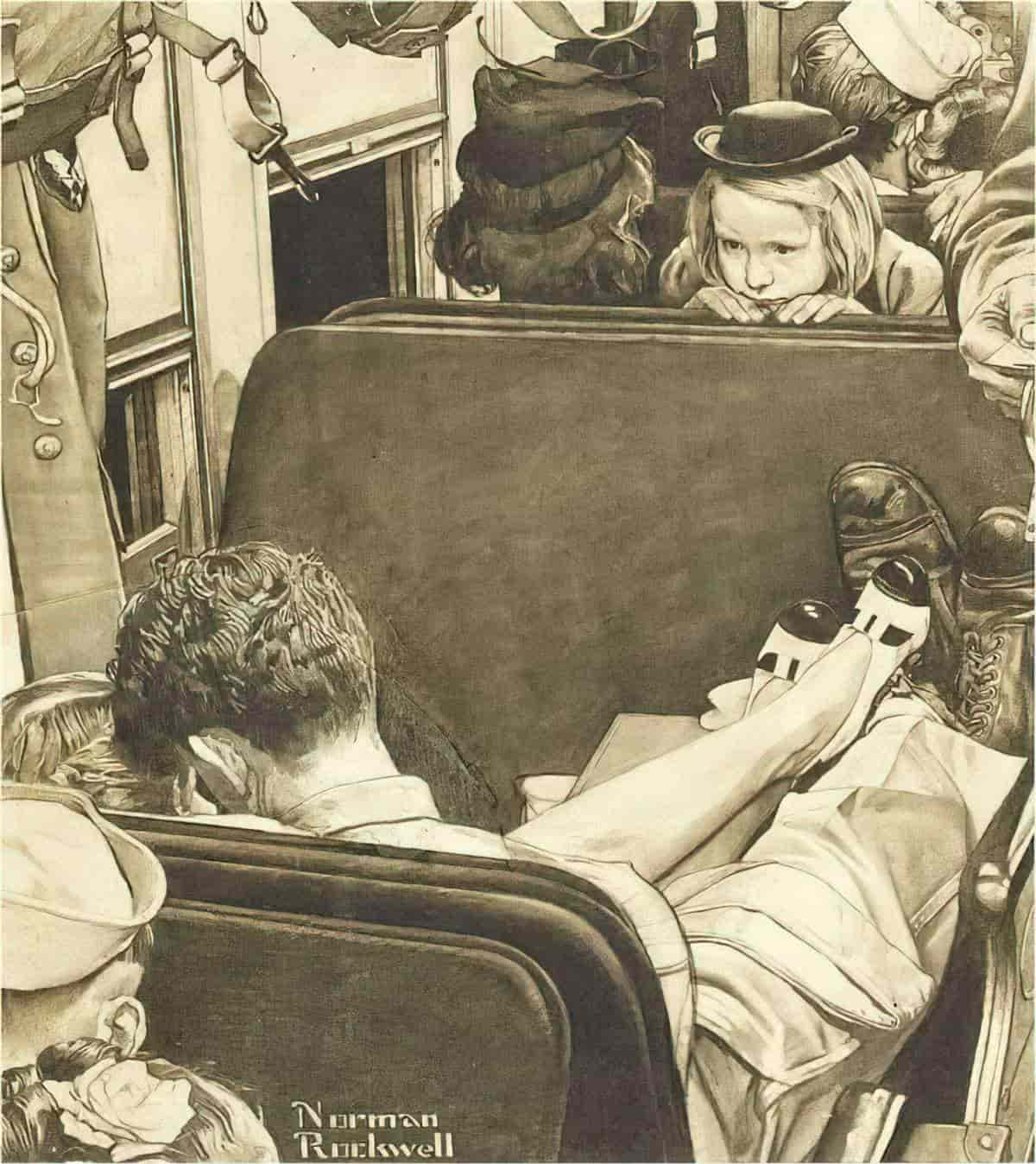

A commentator at the Mookse and Gripes blog likens “Rich As Stink” to What Maisie Knew, which was also my first thought. I’ve not read Henry James’ novella but have seen the film adaptation. What Maisie Knew is the O.G. story of showing the audience a telescoped view of the world through a naive, young girl’s eyes. An extremely limited third person viewpoint leaves the reader to do a lot of heavy lifting, filling in gaps, fleshing out the fuller picture. Interpretations will be various because of what any given reader brings to the table.

After reading “Rich As Stink”, I’m left wondering what the hell is going on with these people. I know something is off, but what, exactly?

Sure, I’m discomfited, but this is masterful storytelling. Isn’t that exactly how we feel, as members of society, when we observe another family, another collection of people, and something just feels… off? We sense something feels wrong, but can’t quite put our finger on it. Too often, we don’t have the evidence to take it further.

I’ve felt this most keenly with a teenage girl I taught, after meeting her father at parent teacher interviews — a single father who seemed quietly dangerous, who complained about his daughter and compared her to his much easier son, unable to accept how difficult it is to be a teenage girl. I observed more closely at that sixteen-year-old girl in my form class, quiet, downcast, and wished she’d tell me — or anyone — what was really going on at home. But I never saw any bruises. And a bad gut feeling isn’t nearly enough, even when charged with reporting duties.

He was a good looking man, which didn’t help. He was so good looking that my boss sat down at my desk after he’d left me reeling and said, “Did you notice anything about K’s dad?” I must have looked baffled because then she said, “I guess he’s too old for you.” And I realised my worldly high school principal at a low SES school had only noticed the man’s good looks. (She hadn’t spoken to him herself.)

Sure, I’d noticed the good looks, but that aspect paled in comparison to his scariness. I asked another experienced older teacher how he had struck her when they spoke. “Did he seem dangerous to you?” I asked, quietly, tentatively. “Yes,” she confirmed. “He seems to me the sort of man who beats women.” But nothing happened after that. Nothing that involved me, anyway.

Munro’s “Rich As Stink” puts me in mind of What Maisie Knew, of”Queenie”, and of various works of fiction. But most of all, this story has got me thinking about real life as a hamstrung bystander.

TECHNIQUE OF NOTE: DISCOMFITING THE READER

How does Munro achieve this? In short, she dripfeeds information designed to disorientate. For another excellent example of the same techniques, see Munro’s “Trespasses” from her Runaway collection. If you don’t mind a difficult and technical read, Nancy Easterlin wrote an entire paper about how Munro disorientates the reader in ‘Who Was It If It Wasn ‘t Me?’: The Problem of Orientation in Alice Munro’s ‘Trespasses’: A Cognitive Ecological Analysis. It’s no coincidence that “Trespasses” is also a story about the experiences of an adolescent girl. Perhaps adolescent girls are uniquely positioned to observe the world, because they’re in that liminal space between girlhood and womanhood, more sophisticated than the younger Maisie (created by Henry James), and at the perfect age to learn something big about the world. An adolescent is still completely dependent on the adults around them, and sees more of an adult relationship than any other adult living outside the house. Adolescent girls can be very savvy, as well as naive — a dangerous but fascinating combination. Just look at the popularity of Lolita.

The following details make me worry for Karin:

- She’s on her own stepping off a plane. These really are different times. Munro tells us that people aren’t really supposed to be coming through the doors to where the passengers are getting off but do anyway. This is something that wouldn’t happen these days. In short, no one at the airport is looking after anyone’s safety, least of all the safety of a self-assured eleven-year-old girl. Anyone could snatch her.

- This eleven-year-old is naive, which we can deduce from some of the psycho narration. But Munro is not sticking to Karin’s voice. At times a dissonant third person narrator tells the reader what eleven-year-old Karin could not articulate, for example when describing Derek’s ‘bright steady eyes and satirical mouth’. This is not a description I’d expect to hear from an eleven-year-old. Yet the description of the Hasidic Jewish men is very much in Karin’s voice. This moving in and out of childlike point-of-view aims to discomfit: Which part of this narration is the authentic, childlike Karin, and which is she repeating, influenced by the adult voices around her? The narration itself creates an uncomfortable juxtaposition.

- Although dressing as a child doesn’t make Karin any less vulnerable to predators (after all, paedophiles are attracted to children, and presumably to all things associated with childhood), our dominant culture primes us to balk a little at preadolescent girls wearing lipstick and other accoutrements of seduction. This is exactly why her own mother doesn’t like it.

- Karin is looking around for an adult man, when I’d expect an eleven-year-old to be glad to see her own mother after a long stint with her father and stepmother. Who is this man to her? Why is he such a dominant presence?

- As the story draws near the climax, paragraphs get shorter, perhaps only one line. The paragraphs don’t segue into one another, creating an increasingly frantic tone. Then the pacing slows right down and we follow Karin in slow motion as she walks from the bedroom to where the adults are.

Much of Munro’s fiction is about the difficulty of establishing authoritative narrative accounts. She has this in common with the literary Impressionists, though they were more interested in the idea that there is no truth. I suspect Munro has in her mind a veridical version of this story, though that’d be interesting to ask her.

In any case, how does Munro disorientate the reader?

- She doesn’t let us know how characters are related. I’m still not sure if the relationship between Rosemary and Derek is/was sexual. An eleven-year-old wouldn’t know this, either. Munro avoids putting us in audience superior position to Karin.

- It took me a while to work out that Karin was as young as she was. At first I thought she was a small college aged student, and when she said she ‘looked ten’, she was exaggerating. My interpretation came from modern parenting in which eleven-year-old girls don’t typically ride planes unchaperoned or buy their own lipstick, or use words like ‘tart’.

Long Days, Short Years: A Cultural History of Modern Parenting

When did “parenting” become a verb? Why is it so hard to parent, and so rife with the possibility of failure? Sitcom families of the past—the Cleavers, the Bradys, the Conners—didn’t seem to lose any sleep about their parenting methods. Today, parents are likely to be up late, doomscrolling on parenting websites. In Long Days, Short Years: A Cultural History of Modern Parenting (MIT Press, 2022), Andrew Bomback—physician, writer, and father of three young children—looks at why it can be so much fun to be a parent but, at the same time, so frustrating and difficult to parent. It’s not a “how to” book (although Bomback has read plenty of these) but a “how come” book, investigating the emergence of an immersive, all-in approach to raising children that has made parenting a competitive (and often not very enjoyable) sport.

Drawing on parenting books, mommy blogs, and historical accounts of parental duties as well as novels, films, podcasts, television shows, and his own experiences as a parent, Bomback charts the cultural history of parenting as a skill to be mastered, from the laid-back Dr. Spock’s 1950s childcare bible—in some years outsold only by the actual Bible—to the more rigid training schedules of Babywise. Along the way, he considers the high costs of commercialized parenting (from the babymoon on), the pressure on mothers to have it all (and do it all), scripted parenting as laid out in How to Talk So Kids Will Listen, parenting during a pandemic, and much more.

New Books Network

- What is the meaning of the title? If Rosemary is ‘rich as stink’, as Derek says, why does she agree to camp in the mobile home? There is clearly an off-the-page financial relationship at play, but what is it? When Rosemary gave up her apartment in Toronto, was that of her own free will? Are Ann and Derek using Rosemary as their bank, in some economically controlling relationship? What the characters say doesn’t line up with what readers observe (are shown). The dissonance disorients. Like young Karin, we are forced to fill in the gaps and, like Rosemary is surely doing, we’re second guessing the situation. (Is Derek really all that bad?)

- There’s a structural circularity to this story, with Karin playing dress-ups both at the beginning and end of the story. As in “Trespasses“, Munro may be subverting the happy ending story, drawing attention to the myth of eternal return. Home is not safe; there is no safe place; there is no home. While the reader is drawn into the circularity, the ‘return home’ of your typical masculine myth is no such thing, and therefore disorients. Is this the ultimate female mythic tale? The tragic version, perhaps.

- In Munro’s short story “Trespasses,” the author delays introduction of the main character, which confounds the reader’s ability to prioritise and evaluate incidents and information. It’s hard for us to work out who’s important here. In “Rich As Stink”, Karin is established as ‘the main’ character from the outset. Instead, Derek is the confusing character. He’s not here in the flesh, but he’s clearly important because we ‘meet’ him before we see him in a scene. Important how? Who is he in relation to Karin’s mother? Is he a nurturing caregiver or is he self-serving?

- By offering the reader only a snapshot through the eyes of a 10/11 year old girl, Munro leaves us standing on the perimeter of the setting rather than entering into it. We are deprived of crucial information.

- The old man in the coffee shop gives Karin a wink which is ‘lewd and conspiratorial’. Karin understands this is because she is wearing lipstick. I assume though the wording is not hers, the feeling very much is. (Munro seems to be writing with the idea that children can understand things even if they can’t articulate them.) But Rosemary laughs at the old man’s joke, ‘taking it for country friendliness’. Why has Munro included this tiny scene? It tells us so much; Rosemary is oblivious to the abusive Derek, just as she hasn’t noticed the lewd wink from this stranger. Rosemary cannot possibly protect Karin, because Rosemary is too deep in her situation to understand any imbalance of power, or the nature of abusive/entitled men. She doesn’t flinch even when the old man says ‘little girl watching her figure?’. Whenever an old man comments on the body of a little girl (which I can tell you is often), this raises alarm bells for me. The word ‘figure’ has sexuality embedded into it (it’s never a word applied to men by men), which sounds the alarm even louder.

SETTING OF “RICH AS STINK”

Munro is well-known for creating an expansive geography, including the fourth dimension of time, and mirroring that in the mental space of her characters. Mark Levene writes in Alice Munro (edited by Harold Bloom) that “new, unexpected and uncertain territory is an essential feature of Munro geography”.

In “Rich As Stink” ‘the problem of occupying space’ in the story … is concentrated on the gloriously innocent ten-year-old Karin (whose name might also be Maisie Farange), who extends her emotions in terms of the spaces around the inside her. Her missing of Derek, her mother’s ‘friend’, she thinks of as ‘the sense that there was space to fill, and a thinning out of possibility’. After the accident in which she is burned wearing a wedding gown, Karin evades her mother’s encroachment, her ‘absurd’ sorrow, by becoming both ‘a continent’ and its minute contraction: ‘something immense and shimmering and sufficient…stretched out like this and at the same time shrunk into the middle of her territory, as tidy as a bead or a ladybug.

Mark Levene

Anything that seems both tiny and large at once is part of the disorientation, almost a form of spatial horror.

PLACE AND TIME

The first paragraph of “Rich As Stink” places us firmly in place and time: Toronto, airport, summer, evening, 1974. However much she disorients us, she never does it by withholding this surface, setting kind of detail. Munro is always very upfront about that. A mistake writers sometimes make is to make the reader guess the era, the place in geography. This is never a fun thing to work out for a reader and should be given to readers upfront, as early as possible. Even when piecing things together isn’t ‘fun’ by design, there has to be a reason to make your readers work.

SYMBOLISM

The land around Rosemary is spotted with juniper. Anytime I read juniper in a work of fiction I tend to link it back to the fairytale “The Juniper Tree”, another old story about a coercively controlling man, casting him as victim, since the one thing men cannot control in a traditional household is what the wife puts into the food.

This link is cemented when, in Ann’s kitchen, Karin’s play acting goes like this:

“The problem is that my husband is really mean and I just don’t know what to do about him. For one thing he has gone and eaten up all our children….”

“Rich As Stink”, Alice Munro

“The Juniper Tree” is, of course, a cannibalistic tale.

CHARACTERS IN “RICH AS STINK”

Karin

The story opens with Karin, so we naturally empathise with her as viewpoint character. Not only that, Munro lets us deep inside Karin’s head. We see the airport through Karin’s eyes, we understand that she is sufficiently young to be caught up in Imaginary Audience Syndrome (concerned with how she’s perceived by others), and that she’s trying on a look, yet to work out who she is.

Karin is parentified by her mother, who understands that she could be sexually objectified by men, but ironically doesn’t see it when it happens under her nose.

I mindfully avoid using the word ‘precocious’ to describe Karin because, when applied to adolescent girls who’ve been encouraged to play adult roles, to attribute an adjective like that suggests there is something inherently mature about the girl, and this takes responsibility away from the adults around her. The word ‘precocious’ also grates because it has been used time and again to describe abused girls in court, funnelling to one result: The word excuses the abuser.

Setting aside common misuses, Karin is not at all ‘precocious’. She’s a typical adolescent girl. She is dependent on the adults around her and therefore aims to impress them. She is drawn towards whichever of the adults will give her time and attention. She likes to play dress up, to look at herself in the mirror and imagine an adult version of herself. She also likes to be tucked into bed by her mother.

Rosemary

Early in the story when Munro pulls away from Karin’s head, she keeps the narrative ‘camera’ hovering above the car. We are not allowed into Rosemary’s head. Instead, Rosemary is described by an omniscient narrator. Rosemary is thereby established as a ‘case study’ of a character rather than as an empathetic one.

The view of Rosemary is not particularly flattering. She is an archetype who might have been labelled ‘hysterical’ last century: nervy, anxious, at the mercy of dysregulated emotion. Will Munro let us inside Rosemary’s head later, I wonder?

It remains unclear to the reader the extent of Rosemary’s culpability as a negligent parent. We have a few snapshots, but Karin’s impression of her mother has been influenced by Derek.

Derek

Munro’s thumbnail introduction of Derek is masterful, partly because he juxtaposes against Rosemary. They are clearly two halves of one (rancid) whole:

Derek was easy to find in a crowd because of his height and his shining forehead and his pale, wavy, shoulder-length hair. Also because of his bright steady eyes and satirical mouth, and his ability to stay still. Not like Rosemary, who was twitching and stretching and staring about now in a dazed, discouraged way.

Rich As Stink

Rosemary met Derek through her job editing manuscript. My own prejudices about certain kinds of people who call themselves writers come in to play; some people have the time and resources to write books but are contemptuous of working ‘inside systems’, and have an inappropriate accumulation of hubris.

Derek goes downhill from there. He’s one of these guys who thinks women are basically crazy. Clearly, only another female character (even if only eleven) could reason with a crazy lady.

Then I look back and remember how Karin wants to please him. I code this as the learned response of a coercively controlled person. This man is far too embedded in Karin’s thoughts, especially considering she only spends summers with these people. How did he do that? It didn’t happen by accident.

The evidence for a coercively controlling man run right through this short story. To list the evidence only from the first three pages of “Rich As Stink”, I make a list to convey the density of evidence:

- “If people like us can break up”, Rosemary tells Karin. This is of course an ambiguous thing to say. It could mean that Derek won’t let her end the relationship without making her life a living hell.

- ‘Derek wasn’t standing behind Rosemary’, observes Karin, suggesting that’s where he almost always is.

- The more dissonant third person narration suggests that what’s on the page isn’t what is true; ‘”Squall” was the name Rosemay and Derek themselves used to describe their fights, which were blamed on the difficulties of working together on Derek’s book.’

- That Rosemary and Derek have been working together on Derek’s book suggests a sublimination of Rosemary’s own desires and career goals. “Why don’t you quit working on the book?” Karin asks. “You’ve got all your other stuff to do.” If Derek doesn’t respect Rosemary in general, I doubt he’d respect her opinions on her book. The editing gig could be a cover for keeping her under his close surveillance.

- Rosemary is lacking the confidence to do ordinary things. She doesn’t like driving, for instance. A common tactic of the coercively controlling abuser is to undermine the confidence of their victim. It’s very common for them to say, “Since you’re not good at driving, I’ll drive you.” To the outsider, this looks like a kindness, when in fact the victim becomes less and less confident about their own driving, and more and more reliant upon the abuser driving them around, increasingly convinced they’re hopeless, increasingly under their control.

- Derek hasn’t told Rosemary where he’s gone, or if he’s gone ‘on a trip’. It’s helpful for the coercively controlling abuser to give their victim the sense that they could pop in anytime without warning, and leave whenever they like. This establishes the hierarchy of dominance and keeps the victim on high alert. Munro uses the word ‘jumpy’ to describe Rosemary. Ostensibly this is because she is not a confident driver. But that is only the surface interpretation. (There’s always an ostensible ‘reason’ for something.)

- We learn that Ann ‘never goes anywhere’. Is this because Derek has two women under his control? Ann has been in Derek’s life longer. Ann is Rosemary’s future self. Alice Munro commonly writes stories about one younger woman, one older, in which the older woman might function as the younger’s older self. (This is one trick she uses for creating a sense of expansive time.)

- We are told by the more dissonant third person narration that Ann has financial means. For instance, she doesn’t have air-conditioning in her car, ‘not because she can’t afford it but because she doesn’t believe in it.’ (I doubt that’s Karin’s wording?) Second, she has bought a quite expensive piece of coffee-making equipment, but Derek has that in the kitchen at what is ‘still his house’. Why has Derek taken a piece of equipment purchased by Rosemary and put it where she doesn’t have access to it? Who does that? Notice how Munro puts this detail inside brackets. Why the brackets? Is this a more omniscient narrator stepping in to clear something up for us? Must be, because this is a detail Karin wouldn’t know at this point.

- “Your mother is addicted to [coffee] places like this because of her awful childhood”, Derek has told the even younger Karin in a flashback scene. It’s a common tactic of coercively controlling abusers to paint a picture of their victims as crazy. This is Derek taking Karin into his confidence, making her feel grown up, which is the reward she accepts while also learning the lesson, from him, that her own mother can’t be trusted. We see that Karin has lost all trust in her mother when she doesn’t want to go out for a trip with Rosemary in case Rosemary gets them lost. The third person narrator tells us, in case we missed it, that Derek tells Karin more detail about Rosemary than Rosemary herself would divulge.

- Derek controls what Rosemary eats, and probably also her ‘medical’ procedures, such as enemas.

- etc.

ANN

We wonder who Ann is. When we meet her, she could be anyone. Is she a family member, friend, neighbour, what? Often, in life, we hear people’s names before we understand where they fit in, and Alice Munro’s stories of social realism mimic the ways in which we really get to know people. Plonking us in the area with no formal introduction is a disorientation technique. We deduce that Ann is Derek’s long-suffering wife.

“How about Ann? Is she still there?”

Rich As Stink

“Probably,” said Rosemary. “She never goes anywhere.”

My read: Derek is using Rosemary economically, and possibly sexually as well, but he is longterm partnered up with Ann. I’m not even sure if Ann and Derek are married, because Derek is a hippie who doesn’t think much of weddings. Has Ann purchased and kept this wedding dress just in case he were to change his mind?

Off-the-page, Derek has used the to classic controller’s tactic of ‘divide and conquer’; Rosemary and Ann were previously on decent terms, but Derek has soured their relationship. We don’t know why or how, just as Karin doesn’t know why or how.

TED

Whereas Derek works ‘outside the system’, Ted is his off-the-page reflection character — a university economist. His job title suggests he is a good money manager, and capable of earning money in his own right, another way in which Derek is different. We know basically nothing about him other than that he has a new partner who likes to attend dress-up parties and that he comes from a rich family.

In an embedded narrative, Karin tells Ann the story of how her own parents met, including the part I wouldn’t expect a child to know. Either Ted or Rosemary have broken the boundaries by parentifying their child (I suspect Rosemary, if either of them), or, Derek has subequently wheedled this backstory out of Rosemary and told Karin himself.

Munro follows this scene with a jump back to the present in which Karin’s mother puts the sleepy child to bed, juxtaposing adult knowledge with a childlike scenario in which Karin is properly parented.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “RICH AS STINK”

Turning now to the basic structure, this is a story that takes place over a day, but with flashbacks included, takes place over a year or so. A story-within-a-story takes us to Rosemary and Ted’s childhood. A sentence or two after the climax takes us forward, past Karin’s burn recovery, and goodness knows how far into the future, in which her intimate relationships are negatively affected because of the man controlling her mother’s life.

PARATEXT

From the title we might expect this will be a story about the rich poor divide. It’s always interesting to put rich and poor people together in a story, and storytellers do this often. In fact it’s not about wealth versus poverty much at all, except in what we might guess.

At first I thought “rich as stink” might be a Canadian expression? A Canadian speaker will have to tell me if it’s Canadian or specific to Alice Munro. I would say “stinking rich” in my NZ/Australian English, or to use the same grammar, “rich as bastards”. New Zealand English tends to put ‘as’ after adjectives as a regional intensifier (“rich as”, “sweet as” etc.) and I’m guessing “as stink” works the same way in this particular dialect.

The story “Rich As Stink” is in a collection about women and their various ways of loving men, so I already know it’s going to be about that.

SHORTCOMING

Like any adolescent, Karin’s main shortcoming is her youth. Eleven-year-olds are at the mercy of adults around them, and their naivety is their main vulnerability.

Eleven-year-old Karin is a strange mixture of knowing and naive, but I find that’s the case with any adolescent. For instance, she knows who Irma la Douce is, but doesn’t know the word ‘Hasidic Jew’, instead describing the men at the airport by their costume: ‘men who wore black hats and had little ringlets dangling down their cheeks.’

DESIRE

Like any adolescent, Karin wants to be a part of something, to imagine herself older, to play as a child when she wants to, to impress significant adults.

The desire that drives this particular story? Near the end she dresses up in a wedding dress. She wants to entertain.

OPPONENT

Every character in this story functions as an opponent for the others.

Derek wants Rosemary to edit his work; she no longer wants to. Ann wants to be her maternal self with Karin but that’s a bit awkward because something off-the-page happened between Ann and Rosemary. Derek may or may not be coded as the Minotaur opponent by the reader — the puppeteer of misery, keeping women exactly where he wants them with sophisticated emotional manipulation. But to me he is clearly terrible.

PLAN

Karin’s plans have been made for her, given her age. But once she gets to her mother’s house she does have a little autonomy so she uses that to visit Ann nearby. She also uses her (sense of) autonomy to go with Derek on his rock-finding adventures, which reveal themselves as underwhelming, not matching Karin’s imaginary, symbolic version of caves and castles.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The climax is of course the scene where Karin catches on fire. Notice what Munro does with the pacing leading up to this scene. She speeds it up then slows right down, then bam, the girl is on fire. It’s shocking how fast it happens, mimicking the realworld sensation of bursting into flame.

ANAGNORISIS

Because Munro has fused Karin’s emotional landscape with the literal landscape, when Karin notices the changes, we can deduce she herself is changing. Notice how Munro lists what is not there rather than what is, signifying a need, a lack:

Karin walked up the gravel road and wondered what was different. Aside from the clouds, which were never there in her memories of the valley. Then she knew. There wre no cattle pasturing in the fields, and because of this the grass had grown up, the juniper bushes had spread out, you could no longer see the water in the creek.

“Rich As Stink”, Alice Munro

The ending is a (disturbing, literal) pyrrhic victory. Whenever there’s a type of mask in a story, and in this case it’s the dressing up, the masked character is in danger. Karin’s dress-up clothes can quite literally kill her, but the symbolism is hardly subtle; she understands the dangers of matrimony, or any sort of formalised arrangement with a man.

After her mask (wedding costume) comes off, Karin better understands the danger of relationships with controlling men…

NEW SITUATION

…but cuts herself off completely, for now persuading herself that it’s either have that kind of relationship or be alone.

This disappointment has been foreshadowed with Karin’s expectations about the rock-finding expedition, in which treasures are cheap mica, the castle and the cave are nothing like she hoped.

Munro has used a geography metaphor to describe Karin’s emotional landscape, so tidies that up at the end with this:

For that was what Karin felt she had become — something immense and shimmering and sufficient, ridged up in pain in some places and flattened out, otherwise, into long dull distancvs. Away off at the edge of this was Rosemary, and Karin could reduce her, any time she liked, into a configuration of noisy black dots. And she herel — Karin — could be stretched out like this and at the same time Shrunk into the middle of her territory, as tidy as a bead or a ladybug.

“Rich As Stink” by Alice Munro

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Why can’t Karin imagine a good relationship with a man? I’d like to know more about her own father. Mainly due to his absence in Karin’s thoughts, I don’t get a Good Father vibe.

I have argued that most of this story resides in what the reader extrapolates. I have extrapolated a man coercively controlling two women, probably by having or promising a sexual or economic relationship with them both. The eleven-year-old daughter of one of those women is going to either be drawn in, or something will happen to afford her a bit of distance. At the beginning of the story, Karin is on a path to being controlled by men, groomed at first by this one.

What is grooming?

[W]hether we’re referring to a children or adults, “grooming” someone means manipulating them into accepting treatment or into going along with something shady, something that is not in their best interest, and/or something the “groom-er” knows the target most likely wouldn’t do if they were just asked outright and allowed to give informed consent. A mugger who demands your wallet at knife-point isn’t grooming you, a con artist who forms a relationship with you so that you’ll give them your money is.

Captain Awkward

The fire is terrible, and highly symbolic, and functions as a torchlight of knowledge gained; after that brief conflagration/illumination she is able to see what’s going on — if not the plot of it, then the feeling of it. Whatever she saw terrified her as much as the flame itself, and most of the scars are internal.

Derek has led directly to Karin’s character change, even if Karin’s response is defensiveness rather than compliance:

…there were people whom you positively ahced to please. Derek was one of them. If you failed with such people they would put you into a category in their minds where they could keep you and have contempt for you forever. Fear… could make Derek decide to give up on her. As he had given up in different ways on Rosemary and Ann.

“Rich As Stink”, Alice Munro

RESONANCE

This story was published in a 1998 collection. The power and control wheel was developed almost two decades earlier in 1982 by the Domestic Abuse Program in Minneapolis but, even in 2020, the very predictable tricks of a controlling person are just starting to be understood by regular people without a psychology/counselling background.

A reader is unlikely to read anything into Derek’s controlling actions unless they have some experience with a controlling person themselves. I suspect “Rich As Stink” functions as an ‘I see you’ story rather than as a ‘teaching’ story. For a more obvious depiction of coercive control, see “Queenie“.

Header painting: John Collier – Fire