Examine the work of rhyming masters like Jane Yolen, Jack Prelutsky, Karma Wilson, Sudipta Bardhan-Quallen and Corey Rosen Schwartz.

Tara Lazar, How To Write Children’s Picturebooks

“If it’s going to rhyme, it’s just terribly important that there’s some repeated phrase, some sort of chorus-y bit.”

Julia Donaldson, The Guardian interview

In 1991 an editor in the children’s department at Methuen contacted Donaldson to ask if she would be interested in turning one of her BBC songs into a book. A Squash and a Squeeze was published in 1993, when Donaldson was 44. It was not expected to be a big seller. For one thing, it was in rhyme, which publishers at the time largely avoided because of difficulties with translation. “In order for a picture book to be profitable, you more or less have to glue some foreign editions on, so you can do a bigger print run,” Donaldson said.

“It was a rule we held to be self-evident that you couldn’t afford to do rhyming books,” [Kate] Wilson, who then worked in Methuen’s rights department, told me, somewhat sheepishly. (The book has since sold more than 1.5m copies, and Donaldson’s work has been translated into more than 50 languages.) Today, a significant proportion of picture books are written in verse, somewhat to Donaldson’s bemusement. “I think there’s far too many rhyming books. And a lot of them – I don’t want to sound vain or anything – a lot of them make me cringe.”

Julia Donaldson, The Guardian interview

What poets do is to encourage our inclination to credit the prompting of our intuitive being. They help us to say in the recesses of ourselves… ‘Yes, I know something like that, too. Yes, that’s right. Thank you for putting words on it and making it more or less official’.

Seamus Heaney, The Government of the Tongue, Faber, 1998

“I fucking hate guys who quote poetry to girls. Since we are being honest. Also, wisdom is a better fat than the vast majority of kisses. Wisdom is certainly a better fate than kissing douches who only read poetry so they can use it to get in girls’ pants.”

from Will Grayson, Will Grayson by John Green and David Levithan

Duke Bunthorne is a character from an opera called Patience. Bunthorne is a poet who frolics around saying poetic things, followed by a hoard of women. [This reminds me of the eerie and inappropriate Canadian-born lecturer of poetry I had at university, who would approach young women in the library, sidle up closely and start reciting poetry at them creepily. He then tricked us all in the poetry exam by letting an entire lecture theatre full of people believe the exam would involve the interpretation of poetry, when in fact we were tested on how well we’d memorised, line for line, the poems of dead white men. We all failed and were all graded up, all of this doing nothing more than demonstrating one of the huge limitations of exams.]

Bunthorne’s lines are a parody of poets who despair at a world in which nothing is special. But there is nothing mysterious about poetry. It uses the same words that we use when making shopping lists or having conversations about football.

Iona Opie and her husband did a lot of work collecting rhymes and games and verse and the literature of play. They focus on the oral tradition.

Beagley mentions a number of good books but I can’t catch them from the podcast. He also mentions a particularly good website by poet Lorraine Marwood. Look especially at the vodcasts in which she works with secondary and primary school aged students.

What is poetry?

In Australia, the bush ballad is distinctive. (The Man From Snowy River is perhaps the most famous example.)

Nursery rhymes can be political parodies, such as Humpty Dumpty. So poetry can parse from one area of the community to another, ending up as a children’s poem.

Tongue twisters are for play.

Most school children and most adults as well have an aversion to poetry. Where does the yuck response come from? Many teachers present poetry to children in an inept way, misunderstanding children’s use and appreciation of poetic forms. What causes the strong reaction to the concept of poetry? Is it technical or about the meaning of the poems?

I have never started a poem yet whose end I knew. Writing a poem is discovering.

Robert Frost

Poetry’s Form and Structure

Sound, especially end-rhyme, has been popular of late but this wasn’t always the case. Alliteration was a more popular poetic technique several centuries ago. Onomatopoeia describes words such as ‘bang’ and ‘slosh’, which are meant to sound like the real-world sound. In blank verse, the enjambment becomes important (where the lines end). Then you’ve got assonance and consonance and different types of rhymes. Because of the stress-timed nature of English, the meter is important. Or the number of syllables. A haiku is the poetic equivalent of taking a photograph. Or the number of lines might be the defining thing, e.g. a sonnet, the limerick.

Other literary devices in poems have to do with meaning, particularly the metaphor. Similes, allusions are other examples. Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah is a good example of metaphor, simile and allusion. The allusion is Biblical — King David is from the Old Testament, the Book of Samuel. Rhythm, rhyme and structure help poems to be memorable.

Plot can be overrated. What I strive for more is rhythm.

Jim Harrison

These techniques compress far more meaning into a short space than would otherwise be possible.

The Difference Between Prose and Poetry

Poetic techniques convey impression, emotion, feeling, idea and other abstractions from meaning, rather than instruction and shopping-list type information. Poets aim to use as few words as possible to convey the most. “The best words in the best order.” G.K. Chesterton said that the aim of prose is for the words to mean what they say, but the aim of poetic words is for them to mean what they do not say. However, writers of prose still have poetic techniques available to them.

The Poetry of A.A. Milne

Disobedience: The last verse is meant to be whispered.

Happiness: A lovely structure of sound and that’s the point of it.

Vespers: Is a breakaway from the other poems. This is a very adult, gushy view of childhood and children were forced to learn it. Parents are just as much an audience of children’s lit as the children, but the meaning is only intended for them. This contrasts with the ‘hoppity hop’ poem which exists as language play.

Other Important Poems

Some poems are very sensual, making use of all the senses. For example Fog by Carl Saunders. There are no harsh consonants, and instead is full of consonants which can be said continuously such as the sibilant ‘sss’, but no plosives. Eleanor Farjeon’s The Tide In The River is similar in this respect: soft sounds repeated, long ‘i’, almost like a nursery rhyme. It also uses the adult image of the tide turning.

Analysis of poetry can draw our attention right away from its beauty. Having said that, you do need to understand the technicalities of a poet’s craft. [This might destroy the poems you study but will help you to appreciate the poems you don’t. It’s a trade-off.]

Beagley then goes on to ruin a war poem. [haha]

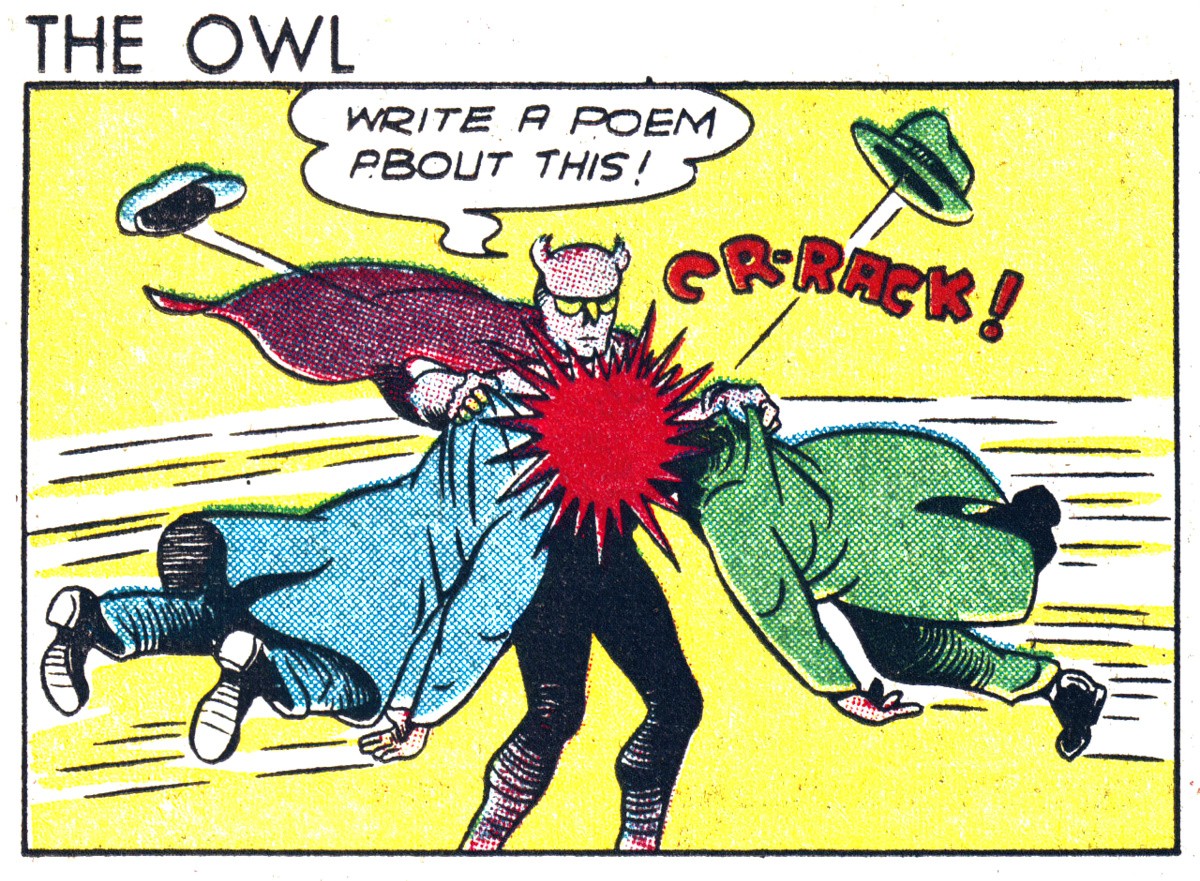

Many wonderful poets are writing for children in the UK. However, if you go searching for children’s poetry in a UK library or bookshop, you’ll find it on a shelf labelled ‘Children’s Poetry and Joke Books’. Children deserve access to the same range of subjects and styles as adults. What public art gallery would fill its children’s’ section with cartoons only? Yes we love cartoons, yes we love humour, but perhaps adult insecurity (about poetry we don’t immediately ‘get’) has narrowed this market to a sub-genre of joke books.”

Manchester Children’s Book Festival

The following are notes from David Beagley, La Trobe University, available on iTunes U.

Poetry is spread through cultures all throughout the world. But children’s poetry is not necessarily a distinct thing — it goes hand in hand with cultures which consider the child different from the adult. What exactly is it that distinguishes children’s poetry from the rest of society’s poetry?

Of all the things I wish I were I wish I were a sparrow

Spoetry

Spoetry is a poem comprising phrases from your spam email folder.

Here’s one from me:

GOOD DAY MY DEAR FRIEND

Black Friday is coming! Prepare yourself!

You’ll never find THIS on a shelf.

USE IT FOR THE CHILDREN.

Poetry book Pictures That Storm Inside My Head poems for the inner you edited by Richard Peck

References

- The Little Book Room by Eleanor Farjeon

- Rebecca Lukens, A Critical Handbook Of Children’s Literature

- A chapter out of a book by Maureen Nimon and Ern Finnis. (This one?)

- Stephen Herrick is an Australian poet who have set styles in place that are being followed all around the world e.g. the verse novel, Love That Dog, where the story is told through a sequence of poems.

Websites useful for finding poems

Searchpoetry.com is a search engine

Those two allow you to search by poet’s name/titles/individual lines. Many of the poems are out of copyright, so older poems.

Bartleby reprints texts out of copyright — old encyclopedias, magazines, classic poems etc.

What Makes For Good Poetry?

Rebecca Lukens (of A Critical Handbook Of Children’s Literature): Simple rhyming and construction of words into a pattern may have a long history, but this is not poetry. Greeting card limericks, advertising jingles etc. are not poems. They are verse, they are games, rhymes, wordplay… but not poetry. Lukens says that poetry as a definition has very specific boundaries. T.S. Eliot also took up this issue: If you’re just playing with structure then you’re not writing poetry. There must be sensitivity of thought that is worth conveying to others. While Lukens does make a case for a continuum, with ‘doggerel’ at one end and ‘high art’ at the other, Eliot is very particular. He says poetry is only at the high art end. Eliot’s own poetry fits at that end — it’s easy to wonder what the hell his poems are about, until you’ve really studied it. That sort of poetry was very popular in the 20th century.

Is this an elitist view? Is this why for a lot of people poetry is meaningless, to be avoided like the plague? You get meaning a lot more quickly from a novel or a movie, or even dance.

According to Lukens and Eliot’s definition of poetry, verse is inferior to poetry.

Poems need to say something about our state of living/human beings/the natural world which adds to our sense of living. What’s more important in poetry: How something is said or what is actually said? It’s insulting to children to say that poetry has to be some elevated form and that they need something different and that children’s verse is somehow inferior.

See Give Them Wings, ed. Maurice Saxby

So those are two opposing views about what makes poetry.

Very often, children’s first introduction to literature (constructed literary works) is rhyme — Round and round the garden, This little piggy etc. Even when the child does not understand the words, they learn the rhythm, they learn that it is comforting, they learn about their relationships with the important people in their lives.

Although nursery rhymes are passed orally from generation to generation, someone must have constructed them. But we have no idea who. (Though we do know who wrote Twinkle Twinkle Little Star – Jane Taylor.)

After a while the child starts to memorise these rhymes and join in. It becomes a shared activity. Actions accompany the rhymes (e.g. Incy Wincy Spider).

This is children’s literature. So how can one say that this is lesser literature than T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets? To the child, this is the complete, greatest thing. Mastering the movements that go along with rhymes is a major achievement.

The very first Simpsons cartoon (a Tracy Ulman show skit) depicts Homer and Marge saying goodnight to the three children. ‘Night night, sleep tight, don’t let the bedbugs bite.’ Lisa is mortified, wondering about the bedbugs. ‘Rock a bye baby…. when the bough breaks the cradle will fall….’ Maggie is imagining herself falling from the top of the tree. Homer and Marge go off to bed and say to each other ‘Aren’t we wonderful parents.’ This skit shows that if children actually understood the words in some famous sayings and lullabies, they’d probably be disturbed. It’s not about the words, it’s about the rhythm and song.

Is it meant to be ‘read’ or is it meant to be ‘said’? This is the question that defines children’s literature.

We’re Going On A Bear Hunt is a very old poetry game. Probably the best known version these days comes via Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury’s book published by Walker Books. Publishing can fix a piece of children’s literature into one well-known form, whereas before publishing, rhymes evolved in the playground.

THE IMPACT OF TV

People who study playground lore have found that, despite worries, TV hasn’t replaced rhymes, chasing, skipping and singing games etc., instead, T.V. has simply added content.

It’s unlikely TV or screens would ever lead to the demise of this kind of play, because playground rhymes offer a safeish space to use taboo language. [Demonstrated in the Australian book series edited by Peter and Virginia Ferguson Durkin.) The rhymes might be about putting someone else down/teasing, or deflates authority and establishes hierarchies. There’s a lot about inclusion and exclusion.

There is quite deliberate parody e.g. Felicia Hemans looking back on the Battle of the Nile, writing the poem Casabianca. The poem was a very didactic one about dying nobly. So the poem had its words replaced in the playground. [We did the same at school with the New Zealand national anthem: Hear our voices tweet tweet tweet/God defend the toilet seat. I remember the joyous terror of singing this in assembly, looking at the teachers trying to work out who was singing it.]

Shirley Hughes’ book is full of things that adults would like, and compared to what the children are using in the playground, it’s not especially memorable.

Walter De La Mare’s poems are deceptively simple and have therefore mainly been published for children. As I Was Walking is a good example of a serious poem which has been hijacked (personalised) by children.

WORDPLAY

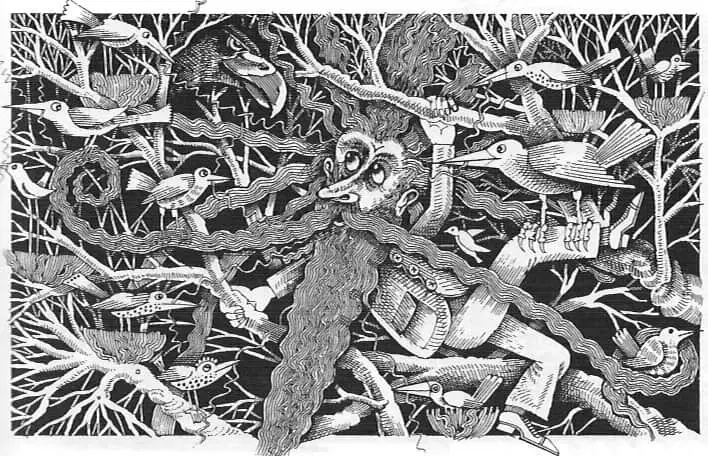

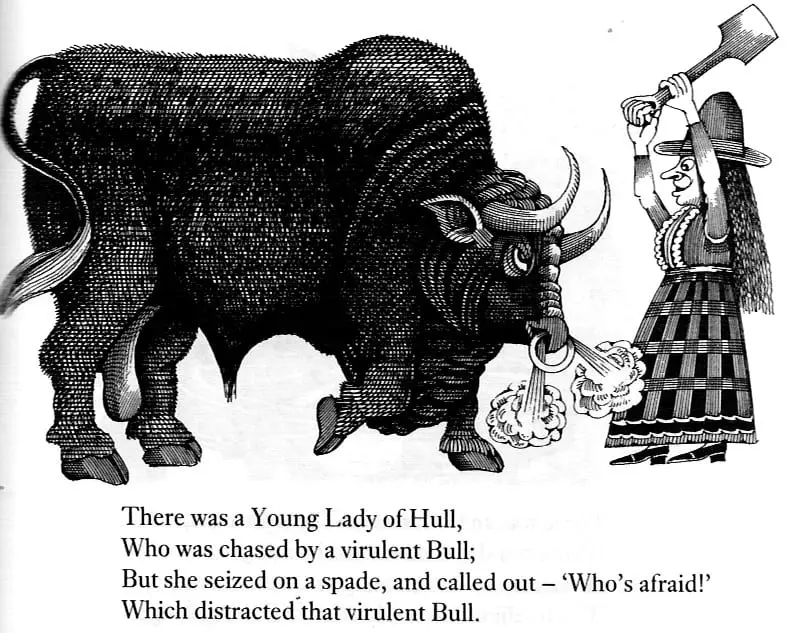

Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, Spike Milligan all wrote poems which made playthings out of words. Some of the words from these famous poets have since entered the English language. (Lear’s ‘chortle’, for instance.)

Sound is very important. Rhyme helps new generations of children to remember the chants.

Related: How To Enjoy Poetry from Brainpickings

FURTHER READING

This is one underlying reason why poetry is so often met with contempt rather than mere indifference and why it is periodically denounced as opposed to simply dismissed: Most of us carry at least a weak sense of a correlation between poetry and human possibility that cannot be realized by poems. The poet, by his very claim to be a maker of poems, is therefore both an embarrassment and accusation.

Ben Lerner, The Hatred of Poetry

Painting is poetry that is seen rather than felt, and poetry is painting that is felt rather than seen.

Leonardo da Vinci

Schoolroom Poets: Childhood, Performance, and the Place of American Poetry, 1865-1917 by Angela Sorby (2005)

When I’m writing, I’m more conscious of the sound, actually, than the meaning. I know what the rhythm of the sentence is going to be before I know what the words are going to be in it. … Silence? Yes. Pneumatic drills? Fine. Traffic noise? No problem. But music is an absolute killer. So I have to have silence, so I can hear the rhythm.

Philip Pullman: Rules of writing from man behind His Dark Materials

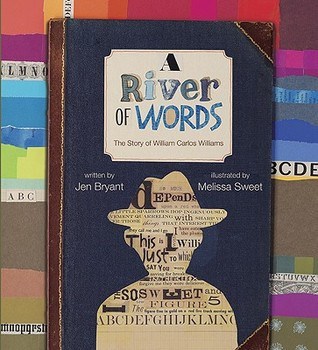

When he wrote poems, he felt as free as the Passaic River as it rushed to the falls. Willie’s notebooks filled up, one after another. Willie’s words gave him freedom and peace, but he also knew he needed to earn a living. So he went off to medical school and became a doctor — one of the busiest men in town! Yet he never stopped writing poetry. In this picture book biography of William Carlos Williams, Jen Bryant’s engaging prose and Melissa Sweet’s stunning mixed-media illustrations celebrate the amazing man who found a way to earn a living and to honor his calling to be a poet.

Don DeLillo once said that when he was writing, all that interested him was the sound. He said something like “I’ll happily change the subject of the sentence for the sake of how it sounds. And I will let the sound dictate the story.

Kevin Barry

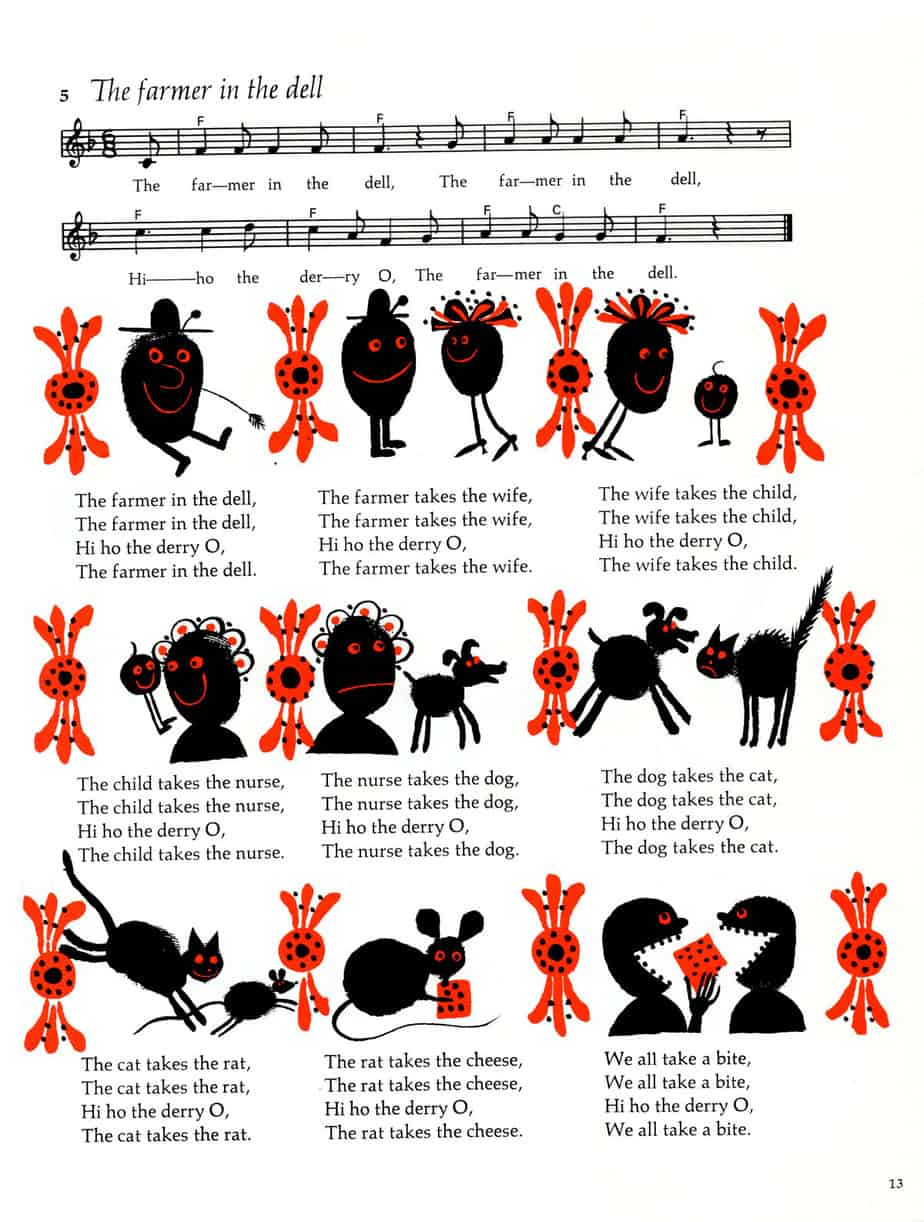

Header illustration: Carlos Marchiori Illustrations for Edith Fowke – Sally Go Round The Sun 300 Songs, Rhymes and Games of Canadian Children (1969), “Farmer in the Dell”.