Reversals and reveals are vital for creating momentum and suspense in a story. Certain genres are required to be more page-turny than others, and all children’s literature must be page-turny. So you’ll find reversals and reveals everywhere in children’s literature.

The first principle of aesthetics is either interest or suspense. You can’t expect to communicate with anyone if you’re a bore.

John Cheever

WHAT ARE ‘REVEALS’?

Peripeteia

A sudden change of events or reversal of circumstances, especially in a literary work.

Contemporary English speakers have a bit of trouble remembering ‘peripeteia’, myself included, so of course ‘reveal’ caught on.

REVEAL

‘Reveal’ started out as a verb, but is now commonly used by writers as a noun. This happened when novelists turned to TV, apparently.

‘Oh darling, [story is] just two or three little surprises followed every now and again by a bigger surprise.

Peggy Ramsay, agent

A revelation is basically a surprise.

Revelation is seen by the audience as motion, even if nothing has changed but knowledge or insight.

In a low-key way, a reveal is simply the answer to a question which the storyteller has prompted the audience to ask earlier in the narrative. The job of scenes is to answer (reveal the answer to) these questions.

The ending of every scene has to be logical; it can’t cheat the readers. They have eagerly read the scene, worrying about a question. So to play fair with them, the conclusion of your scene has to answer the question posed by the goal in the first place.

So if the question was whether the destroyer would sink the sub, the end of the scene has to answer that question. If the question was whether the woman would get the job, the end of the scene has to tell whether she did or didn’t get the job.

from 38 Most Common Fiction Writing Mistakes by Jack M Bickham

WHAT ARE ‘REVERSALS’?

‘Reversals’ are ‘big reveals’. The audience’s understanding of everything in the story is turned on its head. They suddenly see every element of the plot in a new light. All reality changes in an instant. ‘Reversal’ is a term writers use. Audiences tend to just say ‘plot twist’, but that often just means a sequence they weren’t able to easily predict. For example, when Andy escapes in Shawshank Redemption, that’s not a reversal. It might qualify as a twist because we generally expect life-prisoners to stay where they are.

The Sixth Sense, however, includes a genuine reversal because the famous revelation requires us to regard the entire story until that point in a completely different light. The big reversal reveal comes right at the end of the story. This has the advantage of sending the audience out of the theater with a knockout punch. It’s the biggest reason this movie was a hit. (M. Night Shyalaman didn’t come up with the idea of the psychologist being dead until well after his first draft. Though he managed to make it feel very new, Shyalaman was borrowing from a long tradition of Dead All Along characters.)

An example of a reversal is when the audience finds out who A.D. is on Pretty Little Liars. A mistake the writers of that show made was waiting seven seasons to give that information to the audience. Desperate Housewives, the writer’s mentor series, wrapped up mysteries at the end of each season, not at the end of the entire series. This is called a ‘reveal’ but is also a reversal because we realise A.D. was in front of us the whole time. We are asked to think back on everything we’ve seen so far and consider in a new light.

An example of the frustration experienced by viewers when information is withheld across years:

THIS LAST HALF HOUR BETTER BLOW MY MIND BC I WAITED 7 SEASONS TO FIND OUT AD IS SPENCERS TWIN WHEN THAT WAS PREDICTED ALREADY !!! #PLLFinale

@mitamxmaloley, 11:27 AM – 28 Jun 2017

The Greeks called this ‘peripeteia’. A classic example is Oedipus Rex — it’s the bit where he finds out about his parents. Fast forward a few years we have Luke Skywalker finding out who his father is.

A story can have more than one reversal. While minor reversals can occur in every scene, bigger ones tend to divide the work into specific acts.

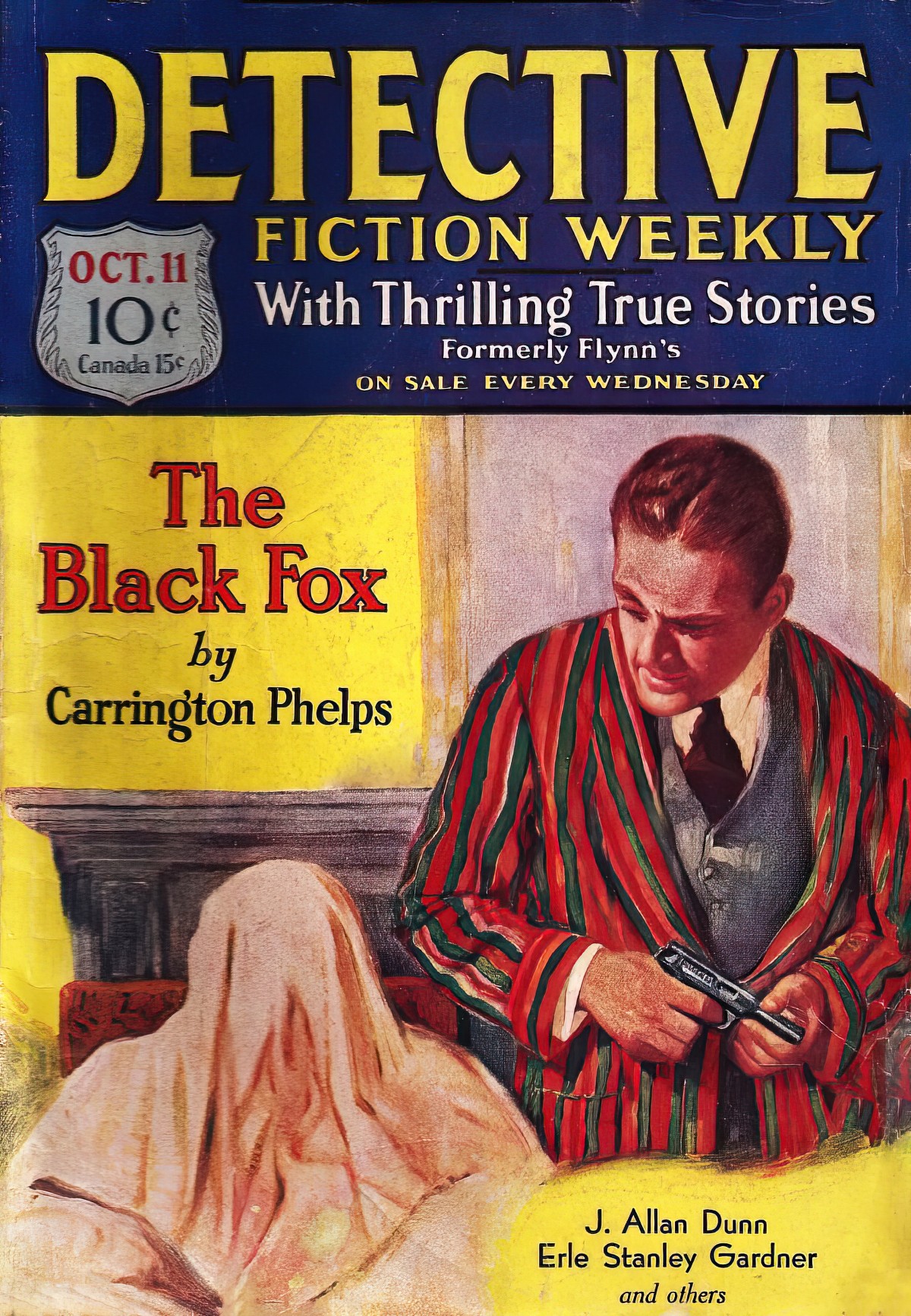

A reversal reveal is most common in detective stories and thrillers.

A subversion is not a modern invention but peripeteia itself. it is the tool that catapults the hero into the opposite of their present state — from thesis to antithesis, from home to a world unknown.

That’s what inciting incidents are too — they are ‘explosions of opposition’, structural tools freighted with all the characteristics the characters lack; embodiments, indeed, of everything they need. Cliffhangers, inciting incidents and crisis points are essentially the same thing: a turning point at the end of an act; the unexpected entry point for the protagonists into the new world; bombs built from the very qualities they lack which explode their existing universe, hurtling them into an alien space of which they must then make sense.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

The final pay off must follow the internal logic established at the beginning of the story. Scooby Doo is hokey, but did this very well.

Here’s a father making his toddler laugh with the Scooby Doo grunt:

Now You See Me (the film) has a twist which doesn’t follow the established logic and is considered a failure. It’s not interesting for an audience to see a 100% change of a character’s personality that has been built up throughout the whole movie.

The best reversal is the kind that creates the biggest surprise without ruining the established logic.

Create suspense by providing the audience with a certain amount of information, then leave the rest to their own imagination.

Alfred Hitchcock

Give the audience just enough to see it coming but not enough to expect it. How to test if the plot twist works or not: The story is rewatchable/re-readable. It should be just as fun if not more fun to go back and see where the writers hint at that twist. This explains why studies show that spoiling a book before a subject reads it makes the reading more enjoyable. The path towards the reversal is more exciting, even though the reader has lost the enjoyment of the surprise. Perhaps this is why lots of stories spoil the ending at the very beginning.

For more on writing a twist ending, see this post.

EXAMPLES OF REVEALS AND REVERSALS

Gone Girl has a big reversal when we realise the victim is bad.

Victimised women who are actually evil in their own right may be a trend started by Gillian Flynn. In the b-grade horror/thriller movie Pet (2016) a stalker captures a woman he’s interested in and keeps her in a cage in ‘the tunnels’ of a dog shelter where he works. Halfway through the movie the young woman is discovered by the security guard. The reversal is that instead of wanting to be saved, the captured woman encourages her captor to murder him brutally. The big reveal is that she is a psychopath and the reason the stalker creep has captured her is because by stalking her he has realised this about her.

Safe Haven is a movie based on a Nicholas Sparks novel, which is fun to watch if you enjoy predicting romantic cliches. The minor conflict, the handsome widower, the woman who kids fall in love with. The downpour of rain, the first kiss… Eventually, however, just when there is nothing left (because they’ve fallen into bed), Sparks gives us the first major revelation: He tells the audience why his main character is being followed. All this time we weren’t sure if she’s a baddie, but now we know she’s the victim, abused and stalked by her cop ex-husband. But another supernatural revelation occurs right at the end, when we realize the woman who has befriended our main character has been a ghost all along. This is a reversal, because it causes us to see the entire progression of the relationship in a new light — this coupling hasn’t happened organically at all; it’s been ‘ordained’ by a higher power.

REVERSALS AND REVEALS DONE BADLY

The Rug Jerk

Any gratuitous plot or character twist tossed in solely to jerk the rug out from under the reader for the sake of surprise or shock, without sufficient foundation, foreshadowing or justification (retroactive or otherwise). Essentially any story twist that violates Chekhov’s principles: “If you fire a gun in Act III, it must be seen on the wall in Act I; and if you show a gun on the wall in Act I, it must be fired in Act III.” The Rug Jerk fires the gun without showing it first or explaining where it came from afterwards.

The Reset Switch, aka The Reboot

Any device that allows a writer to completely erase any already-occurred events of a story and bring the characters back to a predefined starting point, with little or no changes to them or their universe. Time travel (“It never happened”), parallel universes (“It never happened *here*”), unconscious duplicates (“We’re all just clones/simulations/androids of the REAL characters!”) and dream-sequences (“It was all a dream!”) have all been used this way. To be avoided unless the existence of such a phenomenon is, itself, the story’s or series’ central plot point (as in *The Man Who Folded Himself* or *The Left Hand of Darkness*).

Critters.org

A Common Misperception

A misperception I run into a lot: if a reader is not SHOCKED by your big twist, it’s a failure. This isn’t true! Here’s why…

First, guessing a surprise twist beforehand (as long as it isn’t insulting obvious) can make readers feel smart and vindicated to see they guessed right.

Second, when you use a trope where a certain plot twist/reveal is expected, knowing that reveal is coming ADDS to the tension, it doesn’t detract from it. We’re looking forward to him discovering *gasp* his gf is actually the empress! The anticipation is part of the experience.

So: a plot twist can have value not only in being surprising, but also in being anticipated. How to set up plot twists so they’ll delightfully surprise readers OR add to our breathless anticipation when we guess them early: foreshadow adequately, but don’t make it blindingly obvious (unless you don’t mean for it to be a reveal to us, only to another character).

Try to ensure that your reveal will escalate the stakes and/or evolve at least one conflict (the main external one, an internal conflict, or a conflict between characters) in a new way. If it doesn’t change things in some relevant way, it won’t impact readers.

@NaomiHughesYA

Types of Reveals

A few main types of plot twists/reveals:

1. those that surprise us but not the character (this type is used often for unreliable narrators; can be super fun, but can also make a reader feel lied to, so use carefully).

2. The type of plot twist that surprises a POV character but not us. Often used in dual POV stories where one character has a secret that we’re in on, but the other POV character isn’t. Great for driving up tension and anticipation as you build toward the reveal.

And finally, 3. The type of plot twist that surprises (or is meant to surprise; refer to earlier tweet about readers guessing it early not necessarily being a bad thing) both readers and the POV characters. Often happens at midpoint &/or climax.

@NaomiHughesYA

Planning and Editing A Reveals Plot

Further questions to ask:

- Are these revealed secrets worth knowing? There must be a direct impact on the immediate situation.

- Does the audience have enough context for this revelation to be meaningful?

- Is the secret simple? If it needs heaps of explaining it won’t have any punch when revealed. (“Luke, I am your father.” Not, “Luke, I am your cousin thrice removed.”)

- Have you foreshadowed but not telegraphed?

- Like endings, reversals should feel both inevitable and surprising at once.

- Is this so-called revelation simply one of two possible alternatives considered from the beginning? If so, the answer won’t be much of a ‘revelation’ — more like when you’re expecting a baby it’s probably going to be a boy or a girl. The surprise is pretty minimal in that regard. If you’re stuck with this problem, consider audience misdirection or hint at something different but related.

Twist Endings

The Return may have a twist to it. This is another case of misdirection: You lead the audience to believe one thing, and then reveal at the last moment a quite different reality.No Way Out flips you a totally different perception of the hero in the last ten seconds of the film. Basic Instinct makes you suspect Sharon Stone’s character of murder for the first two acts, convinces you she is innocent in the climax, then leaps back to doubt again in an unexpected final shot.

There is usually an ironic or cynical tone to such Returns, as if they mean to say “Ha, fooled ya!” You are caught foolishly thinking that human beings are decent or that good does triumph over evil. A less sardonic version of a twist Return can be found in the work of writers like O. Henry, who sometimes used the twist to show the positive side of human nature, as in his short story “The Gift of the Magi”. A poor young husband and wife make sacrifices to surprise each other with Christmas presents. They discover that the husband has sold his valuable watch to buy his wife a clip for her beautiful long hair, and the wife has cut off and sold her lovely locks to buy him a fob for his beloved watch. The gifts and sacrifices cancel each other out but the couple is left with a treasure of love.

from The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler

My mother hates watching magic shows. She feels she’s being tricked. Of course, she is right. Other people love being tricked. They love magic shows and marvel at the magician’s skill.

I also know readers who hate stories with twists in the tale. They feel they’ve been strung along, manipulated and then lured into a trap as an author’s prey. Other readers marvel at the skill of a tricky writer. These are the readers who can enjoy a tricky ending.

Which kind of reader are you?

When I read a story I always seem to begin playing “Guess the Ending” about two-thirds of the way through. If I’m very lucky, I lose. There’s a disappointment about winning, and delicious fun in being faked out.

Dennis Whitcomb, The Writer’s Digest Handbook of Short Story Writing

Some Classic Films With Twist Endings

Thrillers, horror and mystery seem especially suited to the twist. How many of these do you know and remember? How many did you see coming? Which ones did you like?

- Sixth Sense

- Seven

- The Others

- Signs

- Saw

- The Stepford Wives

- Terminator 3

- Flightplan

Here are some more. Do you agree with the list?

Some masters of story-telling trickery

- Agatha Christie (by setting up false villains. The twist ending is almost mandatory in a good mystery.)

- Roald Dahl (in numerous ways, especially in his short stories.)

- Michael Crichton (e.g. Prey)

Whatever your enjoyment of twist endings (a.k.a. switch endings, the subverted trope), there is much skill involved in doing it well. First of all, inexperienced writers (or readers) may think they are twisting the ending when they’re falling into cliché.

An interviewer asks author Dean Koontz if he comes up with twists as he’s writing, or if the idea for the twist comes first, with the rest of the plot worked around that:

Dean Koontz: Nobody’s asked me that before. That’s very interesting because you just made me realise something. No, I don’t generally think of the twist and then have to go back and plan it. Interestingly enough, those twists that come up strike me. They generally come out of the situation — who the characters are and the traits of those characters, from things that have happened and how they’d react to them. Suddenly [I think] this would be a very logical thing for this character to do, whether it’s the villain or the protagonist.

Ep. 171 – Dean Koontz on writing twists and why writing across genres keeps things interesting as an author, Page One Podcast: The Writer’s Podcast, Friday 18 August 2023

The Wire

John Yorke explains that a ‘twist’ might simply be a refusal to follow the usual story structure — what he refers to as ‘archetypal’ story structure:

Archetypal endings can … be twisted to great effect. The Wire found an extremely clever way of subverting the normal character arc — by brutally cutting it off at an arbitrary point. The death of Omar Little at the hands of a complete stranger works precisely because it’s so narratively wrong; it undercuts the classic hero’s journey by employing all its conventions up to the point of sudden, tawdry and unexpected death. Effectively saying this is a world where such codes don’t operate, such subversion also has the added bonus of telling us just how the cruel and godless world of Baltimore drug-dealing really works.

Into The Woods by John Yorke

If you’re not sure what is meant by archetypal story structure, see here.

HOW TO STUFF IT UP

1. The viewpoint character wakes up and it’s all a dream.

(Didn’t you do this as a kid, at least once? I did, when time ran out in class.) Similar to this: the VP character is actually crazy and it never happened after all. In fact, any ending in which the reader learns ‘It never happened at all’. This is a disappointment because there is no usually no epiphany, nothing to be learned and the reader feels they have wasted their time.

2. The viewpoint character is already dead.

Okay, I recently wrote a story like this but I had to be very careful to make it different.

3. Introduce something random, out of left field, something obviously contrived and tacked on.

Storytelling is like writing a transactional essay in this respect: Never introduce anything new in a conclusion. You’ll end up with classic plot holes.

4. The Shock Value Ending

Someone gets killed off for no good reason. Or similar.

5. Unnecessary Complexity

Some post-modern story-tellers expect an audience to read/watch something more than once, and carefully, before making any sense of it. If this is your style, you’ll attract a specific sort of audience. Many people would rather not put in all that work.

RULE OF THUMB

If you’re going to use a twist ending, have the twist affect someone other than the reader. The twist must affect a character.

DON’T WRITE (UNINTENTIONAL) ABSURDISM

Absurdism was more popular with earlier audiences. Done well, everything does connect, but avoid the bad kind of absurdism where one weird thing happens after another. This is one way to create an unpredictable plot, but unpredictable doesn’t go far enough. Endings have to feel both surprising and inevitable.

It turns out that people don’t actually want to say, “I had no idea that was going to happen!” In fact, they’re often delighted to say, “I knew that was going to happen!” People love to get to know characters, and they feel clever when they can predict those characters’ reactions.

Defying expectations is easy. Creating expectations is hard. To create expectations, you have to write consistent, believable, well-defined characters.

The Secrets Of Story, Matt Bird

AN ALTERNATIVE POINT OF VIEW

Twists are overrated. Predictable isn’t as bad as you think it is. Audiences don’t need a twist in everything, or even in most things, so don’t manoeuvre one in to be tricky.

HOW TO PUT A GREAT SWITCH IN AN ENDING

1. Engender empathy in a character then expose that character for what they really are.

Bad characters are actually good. Good characters are actually bad. Such endings can make us question our own quickness to judge. It encourages us to see shades of grey in character, and this is its own epiphany. The trick-ending has a special kind of ‘epiphanic moment’, known as the ‘anagnorisis’ (discovery) – the protagonist’s sudden recognition of their own or another character’s true identity or nature.

2. Foreshadow without telegraphing.

In a good twisted tale, you can read the story again and see hints at what’s coming. You can enjoy the tale a second time in a completely new way. ‘Telegraphing’ is basically ‘stuffing up an attempt at foreshadowing’ by dropping such heavy-handed hints that any audience with half a wit knows exactly what’s coming at the end. Aim to foreshadow. Avoid the telegraph. At the end of the tale we should see how certain inconsistencies become logical.

Sometimes foreshadowing is done by making use of a ‘plant’ – an object that is ‘planted’ earlier but doesn’t become important until later. The plant is useful in any kind of storytelling, even if there’s no particular twist. e.g. in Six Feet Under, Brenda is writing a novel about the sexual exploits of a fictional character. The audience knows that she is not writing fiction; we’ve seen enough scenes where she has sex with a random stranger, confesses to her prostitute friend then types away on her laptop. One day, she writes a scene about a guy wearing a certain baseball cap. Nate reads her work. Then, while sitting on the veranda with Brenda, the guy turns up, wearing the planted baseball cap. This leads to the end of their first engagement.

Where something – be it an object, situation or character – is introduced early in a story for use much later, this is known as Chekhov’s Gun. Anton Chekhov himself, said that everything mentioned in a short story must have a use. Do not include a gun unless there is some use for the gun.

When the author makes use of false foreshadowing, it’s then called a Red Herring. This is most acceptable in mystery and detective stories. Readers of other genres may have little time for this technique.

SEE ALSO: Types Of Literary Shadowing

3. Irony

For example, after a long hard struggle, we learn the struggle wasn’t necessary. (e.g. Office Space, the movie.)

Or, what a baddie gains wasn’t worth the sacrifice. Can you think of an example?

SEE ALSO: This post on irony

TWIST ENDINGS AND CERTAIN LITERARY TECHNIQUES

1. Flashback

Flashback, or analepsis, comes in useful for a variety of reasons, not least to provide a reader with backstory. In a trick ending, the flashback is used to suddenly reveal information/vital memories which provide the missing information needed to complete the puzzle.

2. The Unreliable Narrator

e.g. Notes on a Scandal (Zoe Heller), “Je Ne Parle Pas Francais” (Katherine Mansfield).

The reader is told a story through the eyes of a certain character who doesn’t quite have the story right. We eventually work out for ourselves that we haven’t been told the whole truth. We meet unreliable narrators in real life, too. Have you ever started a new school or workplace and been told, on your very first day, to avoid certain people in the playground or workplace because they’re idiots or whatever? Eventually, you work out the true balance of power and you realise the person who tried to get you onside on your very first day was the very person who needs friends most, because that’s the person who is ostracised.

3. The Cliffhanger

The ending is unresolved. The characters are left in the lurch.

Some readers really hate cliffhangers. So why would you do this to your readers, who’ve loyally followed you all the way to the end? Maybe to recreate the Zeigarnik effect, in which frustrating and unresolved emotions are those best remembered.

Cliffhangers are best used at the end of a series, and only when another series follows. This will keep the audience coming back for more, without letting them down.

4. Reverse Chronology

The story opens after some pivotal event and works backwards via flashbacks or scenes which are dated and timed. Amnesia stories often work like this: A character wakes up and has no idea who he is. He works it out little by little.

5. Non-linear Narration

Readers have to work hard to get these stories, because we are given a series of random scenes and expected to piece the story together ourselves. Lost makes use of this technique and I, for one, can’t be bothered. Quentin Tarantino does it better in Pulp Fiction. The story may begin in medias res (in the middle of things), jump backwards for say, two thirds of the story, then exist in the present for the final third, after the cliffhanger. These stories are also non-linear, but audiences can grasp these kind more easily.

Remember, when matching wits with the reader, that your readers will be on the lookout for the twist in the tale. Especially readers of short stories, who tend to be the most widely read group of people of the lot.

Related Links

Tara Maya talks in terms of the ‘plunge’ ending versus the ‘twist’

A Goodreads list of books with twist endings

Twist and Shout? – The literary twist considered from Sulci Collective