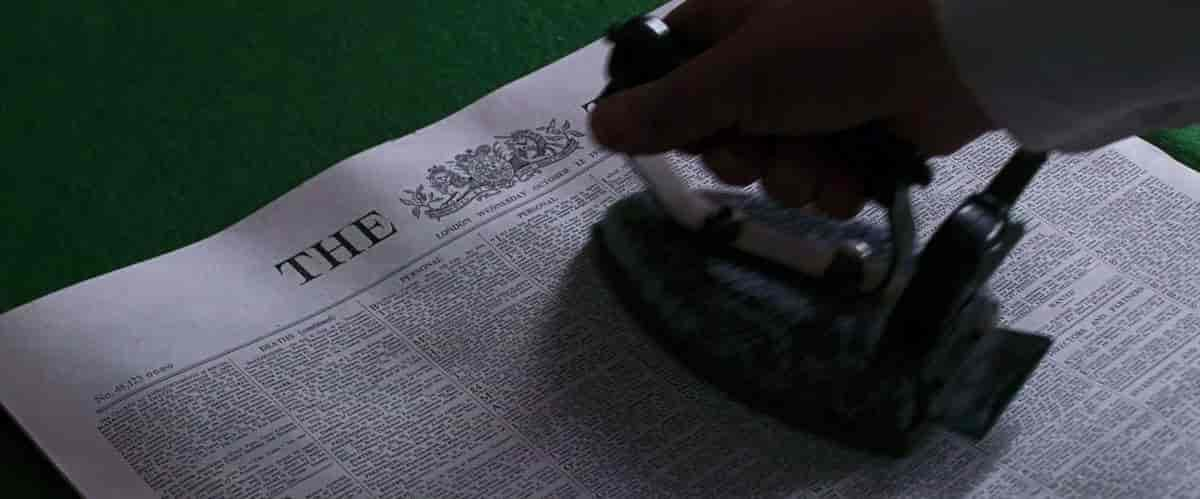

The Remains Of The Day by Kazuo Ishiguro won the 1989 Booker Prize. Ishiguro was 35 years old at the time and this was his third novel. The book was adapted for film in 1993, starring Anthony Hopkins as Mr Stevens and Emma Thompson as Miss Kenton.

THE REMAINS OF THE DAY BY KAZUO ISHIGURO

In the summer of 1956, Stevens, a long-serving butler at Darlington Hall, decides to take a motoring trip through the West Country. The six-day excursion becomes a journey into the past of Stevens and England, a past that takes in fascism, two world wars, and an unrealised love between the butler and his housekeeper.

Kazuo Ishiguro wrote the draft in a flurry of activity; it only took a month, while he asked his wife to relieve him of all life duties for the duration. (This author can also take ten years to write a book.) He didn’t do much research to begin with. He just wrote. There wasn’t all that much to be found about the life of servants anyway, which is unfortunate given how very many people worked as servants. Their histories have been largely lost.

However, these days there is more to be found about servants. I highly recommend listening to what Lucy Lethbridge has to say about England’s servant class. Lethbridge is the author of a book called Servants, published 2013. She interviewed people who had worked in service as well as people who had employed domestics.

SERVANTS: A DOWNSTAIRS VIEW OF TWENTIETH-CENTURY BRITAIN BY LUCY LETHBRIDGE

From the immense staff running a lavish Edwardian estate to the lonely maid-of-all-work cooking in a cramped middle-class house, domestics were an essential yet unobtrusive part of the British hierarchy for much of the past century, required to tread softly and blend into the background. Lucy Lethbridge’s Servants gives them a voice in this discerning portrait of the complex relationship between the server, the served, and the world they lived in, opening a window on British society from the Edwardian period to the present.

Where does The Remains of the Day fit in the category of servant-master fiction set in big, aristocratic houses?

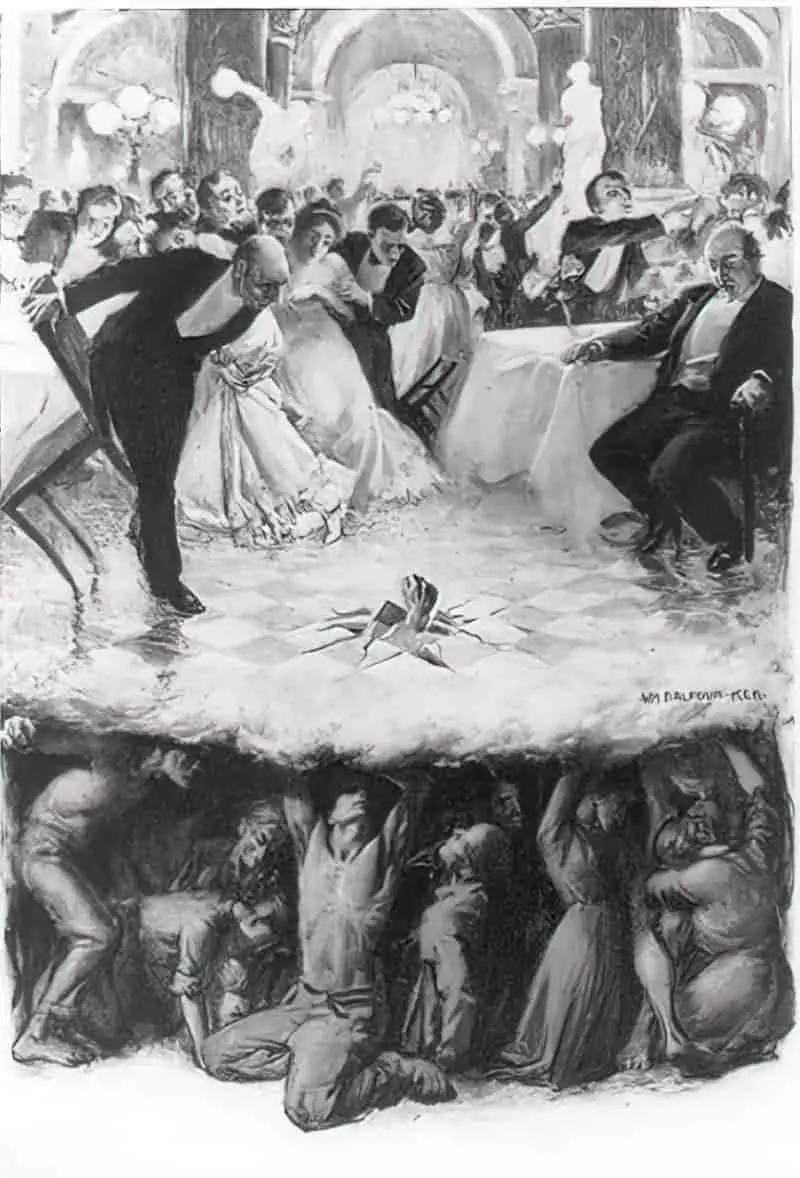

Upstairs, Downstairs was an English TV series which ran from 1971 for five seasons total. This show was immensely popular. It’s worth noting that Upstairs, Downstairs appeared on televisions as soon as the servant life disappeared in the real world. Basically, as soon as this ostentatiously hierarchical way of life disappeared, the hegemonic culture began to romanticise it.

Writers of Upstairs, Downstairs believed the show to function as escapism. British audiences were plagued by problems caused by economic turbulence of the 1970s, and were struggling to adapt to a new, individualistic era.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day appeared two decades after Upstairs, Downstairs first broadcast. Unlike its super popular predecessor, Ishiguro’s novel did not serve as escapism, and did not encourage audiences to look back on the servant era as cosy and quaint. Instead, Ishiguro’s take encouraged audiences to mourn all of those lost lives, spent invisibly and fruitlessly serving ordinary fellow humans with ordinary human foibles, and far too much influence for everybody’s good.

Though widely acclaimed, The Remains of the Day did not put an end to romanticisation of the servant-master class in popular fiction.

Far more recently, Downton Abbey has garnered huge, adoring audiences. Downton Abbey (and also Brideshead Revisited) returns audiences to a sentimental era, in which everyone “knows their place”, set in houses where masters treat their employees benevolently in kind. Downton Abbey was written by a conservative peer who really seems to believe that those days of the great manor house were the good old days.

Downton Abbey does capture the below-stairs, above-stairs hierarchy very well, and the writer is himself very familiar with this world (from the upstairs point of view). Kazuo Ishiguro offers glimpses of this division, but also focuses on the hierarchy which happens behind the green baize door. The below-stairs hierarchy is at least as stratified as the hierarchy upstairs. Mr Stevens would very much consider himself above the other staff. The butler carves the roast in the servants’ kitchen, which is a shadowy reflection of what’s happening upstairs in the drawing room. He is like the master of the house, but not quite.

Clearly, today’s audiences have a high tolerance, or even a deep-seated craving, for domestic stories featuring stringent social hierarchies in beautiful big houses with manicured grounds.

But are audiences more inclined to imagine themselves in the shoes of a domestic or of a Crawley upstairs?

Modern audiences cannot possibly imagine the utter drudgery of the life of a scullery maid from the mid 20th century and earlier. If you look at manuals for housemaids from that earlier era, housemaids were encouraged to treat the tables and chairs with tender loving care, right behind her own family in level of affection. The job of servant was an identity rather than a job, requiring complete sacrifice. Even the most kindly employers were limited in their kindness. Servants were always just servants. They certainly didn’t want their servants to step outside their roles to fulfil their own personal hopes and dreams.

However, in Downton Abbey, we very rarely see the servants actually doing any housework. (If we did, the story would not find such wide appeal.)

Short Summary of The Remains of the Day

It is the summer of 1956. British society is in the throes of change. Stevens is an English butler who serves in the household of Lord Darlington. Via first person narration, the story is cast as a travelogue as Stevens goes on a solitary road trip. Lord Darlington insists. After all, Stevens is so loyal and trustworthy. He deserves a holiday.

Stevens is driving the luxury car which belongs to the “great gentleman” Lord Darlington and is thereby mistaken for a member of the upper class. This sits awkwardly with Stevens, who is used to a lifetime of self-abnegation.

On his road trip, Stevens looks back at his time in service and recalls a young housekeeper and her desire to strike up a relationship with him. Stevens was passive in the face of her moves. She moved away and got married to someone else. But now Stevens is nearing the end of his life and is having complicated thoughts about his decision to devote himself entirely to service.

He recalls the interwar period, and confronts the difficult reality that he was in service to a man whose political opinions he does not understand. If he did understand, he almost certainly would not share them. It has been in his own best interest to ‘half know things’, not only regarding himself and his own personal desires for human connection and someone to call family, but also to half know things about the men he has devoted his life to.

Is The Remains of the Day Sad?

The story is very sad if you can hook into the repression and regrets suffered by Mr. Stevens. It’s sad because with every decision we make in life, another life path closes off. This only becomes apparent in middle age, but is in fact true all throughout our lives. If we embrace this reality, we can make peace with it. But until we make peace with a lifetime’s worth of closed-off opportunity, we suffer.

Ishiguro himself has said that his novel is a portrait of a “wasted life”. But let’s interrogate Mr. Stevens’ life through a modern, 2020s lens.

MR STEVENS, ENGELS AND FALSE CONSCIOUSNESS

Philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels talked about an idea called ‘false consciousness’ in regards to workers.

Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) used the term “false consciousness” in an 1893 letter to Franz Mehring to address the scenario where a subordinate class wilfully embodies the ideology of the ruling class. Engels dubs this consciousness “false” because the class is asserting itself towards goals that do not benefit it.

Wikipedia

Basically, workers are engaged in an illusory mindgame in which they believe their lives are meaningful, when all along they’re doing the work for the upper classes, helping them to become more and more prestigious and wealthy. Mr Stevens is simply an extreme example of today’s corporate employee.

For more on False Consciousness, see Chapter Five of Sara Ahmed’s book The Promise of Happiness. Ahmed considers two films–Children of Men and Michael Bay’s The Island–to illustrate the concept. Ahmed’s main point is that, by adopting norms such as the false consciousness (that we are happy when all along we’re working for someone else) we are doing nothing at all to ensure happiness as a broad concept which includes everyone. ‘Happiness’ is problematic, but we can ‘live happily’ only when we become revolutionaries, drawing attention to inequality. The tragedy for Mr Stevens is that he never moves beyond false consciousness. He does eventually realise that his employer was a problematic person, but he sticks to the narrative that no one’s perfect anyway.

MR STEVENS AND NORMATIVITY

There is increasing acknowledgement that we are all shaped by a society with strong normative expectations. In the 1980s when Ishiguro wrote this novel, everyone was still expected to be sexual (i.e. not asexual), cisgender, romantically oriented, heterosexual. Family is still king. Even with wider acceptance of gay and lesbian partnerships, the idea that someone like Mr Stevens might be happy as a single man is not an idea celebrated by literature.

Why is The Remains of the Day so good?

Remains of the Day was endearing, heart breaking, subtle and just BEAUTIFUL. For such a short book, it packed a punch. The simplicity of Steven’s thoughts, the way everything unfurled in which the reader understood him more than he understood himself, that entire bit where he wanted to practice bantering, and when he tries to sideline crying on his mother’s death….is lovely and heart breaking. This is the quality of a good book, it makes you reflect on your own life and I am glad that I got to learn from his experience

Unreliable narrators: Pale View of the hills & Remains of the Day, sunsedge

The romantic trope of The Erotics of Abstinence remains popular, and explains the popularity of stories from Pride and Prejudice to Twilight.

Related to ‘abstinence’ is a more general ‘repression’. As a Japanese-English author, Kazuo Ishiguro is in a good position to overlay a traditional Japanese sensibility onto the required suppression of England’s pre-war servant class, and he does this extremely well.

Ishiguro’s previous works were A Pale View of the Hills and An Artist of the Floating World, both set in Japan.

ARE THEMES UNIQUELY JAPANESE?

In White Lotus (2021), Armond tells a new employee at the luxury resort:

It’s a Japanese ethos, where we are asked to disappear behind our masks

as pleasant, interchangeable helpers. It’s tropical kabuki. The goal is to create for the guests an overall impression of vagueness that can be very satisfying. Where they get everything they want – but they don’t even know what they want or what day it is – or where they are – or who we are – or what the fuck is going on.(sours; spots something)

Looks like there’s a dollop of mayonnaise on your top, Carmen.

White Lotus, Season One, Episode One

White Lotus, written by a Westerner for Western audiences, evinces the widely-held international view that the Japanese are a uniquely self-effacing culture. The concepts of omote and ura are well-known. (Do we have equivalent English words in use outside the field of psychology?)

But is anything uniquely Japanese?

Especially in the age of the Internet, perhaps, there’s a trend in which non-Japanese commentators make lists of ‘uniquely Japanese X’ (words, concepts, customs, quirks). Oftentimes, the lists include many things which are not uniquely Japanese at all, shared across cultures. The lists are therefore othering, positioning Japanese people as inherently unknowable; too weird to fully understand, with a history too different, too isolated from our own.

Reviewers of the novel pointed out the Japanese-ness of the novel, writing things such as:

Stevens speaks of uniquely Japanese themes within the context of a British upper-class household: the matter of personal honor; the necessity for determining the moral status of an employer; of a group named “the Hayes Society” which determines the standards for “greatness” in a butler; of personal “smells”; of loyalty as a basic trait of character. The easiest analogy, of course, would be the traditional Japanese relationship between vassal and lord, which is a popular theme in Japanese novels an films.

But what makes the understate assumptions of the novel more Japanese than British is the emphasis placed by Mr. Ishiguro on “frame” (ba): the definition of one’s self in terms of one’s associates, rather than on the Western concept of “attribute” (shikaku)—status acquired by birth or by individual achievements.

The point of view is also, in an understated way, particularly Japanese. Stevens, as a servant with no real access to the centers of power, occupies the position of the madogiwazoka—”the man who sits by the window” and observes. This is a privileged perspective, one which enables the powerless observer of the center of power to make significant moral judgements.

Ploughshares, James Alan McPherson Vol. 16, No. 4, The Literature of Ecstasy (Winter, 1990/1991), pp. 282-283

If author Kazuo Ishiguro did not have a Japanese name and Japanese ancestry, would reviewers and readers be so quick to notice how very Japanese the story is? Might they instead talk about how very English it is?

This question raises interesting questions about author identity forming part of the paratext of a work, meaning, what we know about who wrote a text influences how we read it. Fast forward to the age of social media and authors are now expected to market their own identities, sitting as ‘product’ alongside the products of their books.

Aside from that, other commentators position The Remains Of The Day comfortably in a long tradition of English literature:

Its masterfully subtle, seemingly discursive first-person narrative is reminiscent of Henry James at his best, with certain aspects of the plot echoing “The Beast in the Jungle” in particular; Stevens’s painful, retrospective revaluation of character and incident is comparable to that in Ford Madox Ford’s Good Soldier, and Ishiguro’s evocation of time, place, and class is as carefully wrought as (though on a far less massive scale than) its counterpart in Anthony Powell’s Dance to the Music of Time. Still, because servants are incidental in the works of Powell, Ford, Waugh, and (often) James, such “marginalized” characters’ perspectives have rarely if ever been considered in detail. Ishiguro’s novel thus makes a new and valuable contribution to—while also managing to subvert significant conventions of—this literary tradition.

William Hutchings, University of Alabama Birmingham, World Literature Today

Vol. 64, No. 3, O.U. Centennial Issue (Summer, 1990), pp. 463-464

EXCELLENT ACTING

Sir Anthony Hopkins received tips on how to play a butler from real-life butler Cyril Dickman, who served for fifty years at Buckingham Palace. (Hopkins has said more recently that now he’s an old man he doesn’t have to act as an old man — it comes very naturally. See, for instance, another masterful old man performance in The Father.)

Emma Thompson is also excellent as Miss Kenton.

Did The Remains of the Day film win any Oscars (a.k.a. academy awards)?

Yes, many:

- Best Picture

- Best Actor in a Leading Role

- Best Actress in a Leading Role

- Best Director

- Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material Previously Produced or Published

- Best Art Direction-Set Decoration

- Best Costume Design

- Best Music, Original Score

ANALYSIS OF THE REMAINS OF THE DAY

Who is the main character in The Remains of the Day?

How do we determine the main character of any story? Generally, it is the character who changes the most, not in circumstance but in worldview. They are the character who has the biggest epiphany.

Does this description apply to the repressed Mr. Stevens, who continues to repress his feelings until the end, in this tale of a love tragedy?

We could say that Miss Kenton is the ‘secret’ main character because Miss Kenton/Mrs Benn enjoys a fuller, more varied life, with its ups and downs and its attendant self-growth.

Yet the story focuses on Mr. Stevens, and his world has changed around him. Since Mr. Stevens basically equals the house, and the house itself has undergone a character arc, of sorts, we can still confidently call Mr. Stevens the main character of this story.

Also, due to his unreliable narration, we don’t really know how much he has changed. We only know what he is telling us — that he has every intention of spending the rest of his life content.

MR STEVENS, LOYAL AND SELF-EFFACING MANSERVANT

Mr Stevens is the last of a breed: a man servant for England’s aristocratic class. Born near the end of the 19th century, Stevens has spent much of his life serving a gentleman called Lord Darlington, who he believes to be a fine, upstanding and very kind man.

Serving as butler requires Prufrockian traits.

Prufrockian: Of or relating to The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, a poem by T. S. Eliot, published 1915, marked by weariness, regret, embarrassment, and longing.

Why is the novel called The Remains of the Day?

A man’s life is shrunk down to the cycle of a single day, in which dawn is birth and evening is late middle age. When darkness comes, that will mean death. The Remains of the Day suggests a character who is reassessing his life in late middle age and contemplating what the remainder will hold.

With fresh clarity and a concerted suppression of regrets, Stevens tries to change the course of his fate not by leaving the house where he has held employ his whole life, but by trying to reinstate the former housekeeper who left two decades ago to marry another man.

What time period is The Remains of the Day set?

When Stevens goes on his road trip it is 1958. He looks back on when he was younger, to the period before, during and just after WW2.

Did Lord Darlington Exist in real life?

Lord Darlington is a fictional character, but based on a class of aristocratic men who had been used to the privilege and influence afforded to them due to their class, and who got a rude awakening after WW2, when the culture around them changed and they were no longer as politically influential.

Ishiguro chose to create a gentlemanly dupe to illuminate how terrible things can be when major political decisions are left to a ‘gentleman class’ who know nothing about international relations.

BY THE 1950S ENGLAND HAS CHANGED

When the story opens it is the late 1950s, an time of change for those magnificent old buildings in England. A large number of private owners are no longer able to afford maintenance on their luxury estates. The expensive estates are being handed over to the National Trust, or to the new rich (creating a snobbish divide lampooned in To The Manor Born).

What happens to Lord Darlington in Remains of the Day?

Lord Darlington has died three years earlier. As an older man he confided in Stevens that he had treated the Jewish maids very poorly by sending them away at his fake friends’ behest.

ENTER THE NOUVEAU RICHE: THE AMERICAN MR FARRADAY

A mysterious but ultimately jovial American arrives at the real estate auction and buys Darlington Manor, including all its contents.

Next, he orders everything be returned to its ‘rightful’ place. He wants a real, genuine English manor. The continued employment of Mr. Stevens came as a ‘package deal’. The American’s name is Farraday. He’s determined to live the life of a stereotypical English gentleman, and even takes up hunting. (Lord Darlington despised it, presumably due to its cruelty. This single detail thereby says something important about both Lord Darlington and Mr Farraday.)

THIS NEW AMERICAN IS UNUSUAL

Both the upper classes and working classes agreed that the middle classes are awful. The servants would have their own servants, oftentimes — a mother who works by day as a domestic servant might pay a few pennies to a neighbour girl to look after her own children. Even as late as the 1950s, many servants had the absolute certainty that old money equals virtue. What Mr Stevens and Lord Darlington had in common: A hatred of new money. In fact, servants would despise new money more than anyone. It is a massive shift in circumstances for Stevens that his new master is new money.

So it takes Mr Stevens a while to get used to this new American he works for. He doesn’t understand when Farraday is pulling his leg, for instance. Clearly, Farraday is himself unused to having an English man servant himself, treating Stevens as a bit more of an equal than the aristocratic Lord Darlington ever did.

MR STEVENS DECIDES TO LEAVE THE HOUSE AND REUNITE WITH AN OLD LOVE

Mr. Farraday is also in need of a new housekeeper, and Mr Stevens has someone very particular in mind: A Miss Kenton he worked with twenty years ago, during the war. Well, she’s called Mrs Benn now because she married another man she and Stevens both worked with. Mr Benn required a proficient woman to open a bed and breakfast with, near the sea.

Why does Miss Kenton leave Darlington Hall?

Decades later she admits to Mr Stevens that although she agreed to marry and open a bed and breakfast, she never really thought it would happen. (Marriage really was the only escape for woman servants, and for some man servants, too.)

The whole time, Miss Kenton probably expected Mr Stevens to finally admit his feelings, at which point she would have reason to pull out of it. By getting married in those days, employed women lost some of their freedom.

But to marry was still the normative, idealised life, and Miss Kenton also revealed (in a discussion with Mr Stevens about why she didn’t throw in the job with the dismissal of the Jewish girls) that loneliness is her biggest fear. She married to avoid being lonely.

Was Miss Kenton in love with Mr Stevens?

There are few things more lonely than unrequited love, or love which goes unacknowledged. So it would have seemed less painful to leave than to stay at Darlington Hall working alongside Mr Stevens.

Was Miss Kenton in love with Mr Stevens, or with the idea of Mr Stevens? Mr Stevens revealed so little of himself, Miss Kenton could have imagined a whole different life in which Mr Stevens was the exact man she desired.

However, the pair did have much in common: Their attention to detail, their commitment to their job, their basic adherence to hierarchy, their tendency to take personal offence where none was intended.

Ezra Klein: What is status to you?

Status Games, Polyamory and the Merits of Meritocracy

Agnes Callard: It’s how much value other people accord you. […] The importance game is a game of jockeying for status, in which you try to be recognized by your interlocutor at sort of the maximum importance level that they can recognize you at. So you want to give them all the facts that they would need to see how important you are. And the leveling game is a game of finding common ground in feeling unimportant. So you find a way to talk to someone in such a way that you can both share an experience of powerlessness or struggle. And in a way, it’s a way of deflecting from the importance game.

THE ROAD TRIP BEGINS

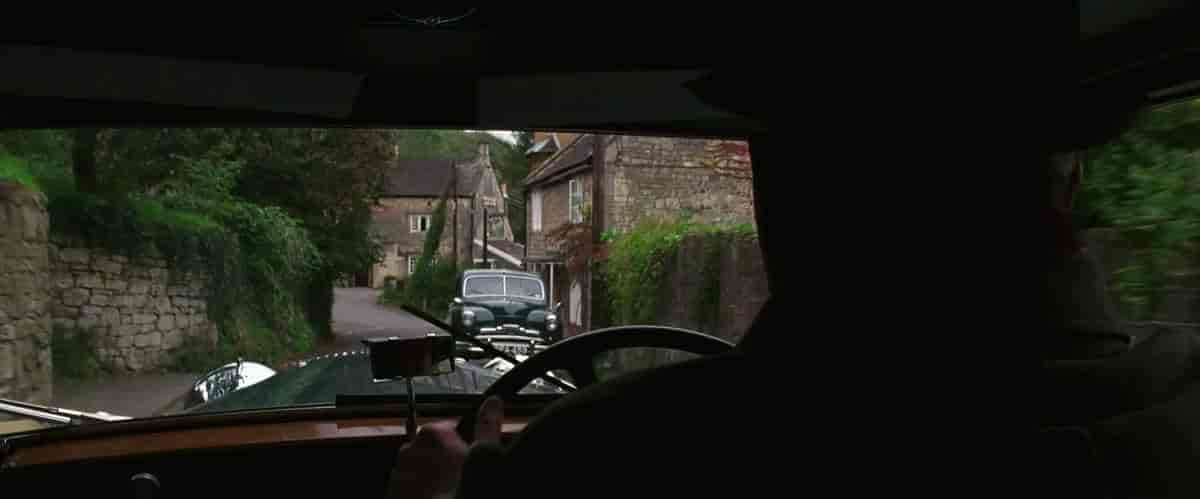

Mr Stevens borrows his new employer’s luxury car and sets off on a rare road trip to reunite with Mrs Benn and find out whether she might be interested in returning to Darlington Hall.

MISTAKEN FOR A GENTLEMAN

While on the road trip, Mr Stevens is himself mistaken for a gentleman by people he encounters, due to his using a luxury car, and also because of his dress and manors, which look just like that of a gentleman to the untrained eye.

The time-hallowed bonds between master and servant, and the codes by which both live, are no longer dependable absolutes but rather sources of ruinous self-deceptions; even the happy yokels Stevens meets on his travels turn out to stand for the post-war values of democracy and individual and collective rights which have turned Stevens and his kind into tragicomic anachronisms.

Salman Rushdie: rereading The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

Why does Stevens deny working for Lord Darlington?

The English butler, the shadow that speaks, is, like all good myths, multiple and contradictory. … the butler as liminal figure, standing on the border between the worlds of “upstairs” and “downstairs”

Salman Rushdie: rereading The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

By 1958, Lord Darlington has garnered a reputation among locals for being a Nazi. It is well-known that he was bamboozled and manipulated by Nazis into working for the German cause. As a Lord, he felt he knew more about politics than he really did, but gentlemen’s manners don’t go very far when it comes to politics, and especially not when it comes to law. With good intentions and an admixture of gentlemanly, aristocratic hubris, he thought he was doing the right thing by trying to intervene between England and the Germans, but he only ended up making things for England worse, betraying war secrets after being manipulated by far more canny German men.

So when Mr Stevens goes for his road trip and meets people who know of Lord Darlington, he’d rather not get into it with them. He doesn’t know how the conversation will go. Also, he spent much of his working life serving Lord Darlington without question, and it is psychologically painful for him to admit, even to himself, that he spent his life in service to a disreputable man.

STEVENS REFUSES TO ADMIT THAT LORD DARLINGTON WAS A TURD

Stevens is unused to car maintenance and the car stops running. A much younger man helps him out. This young doctor is able to discern the fine differences which mark Stevens out as a man servant.

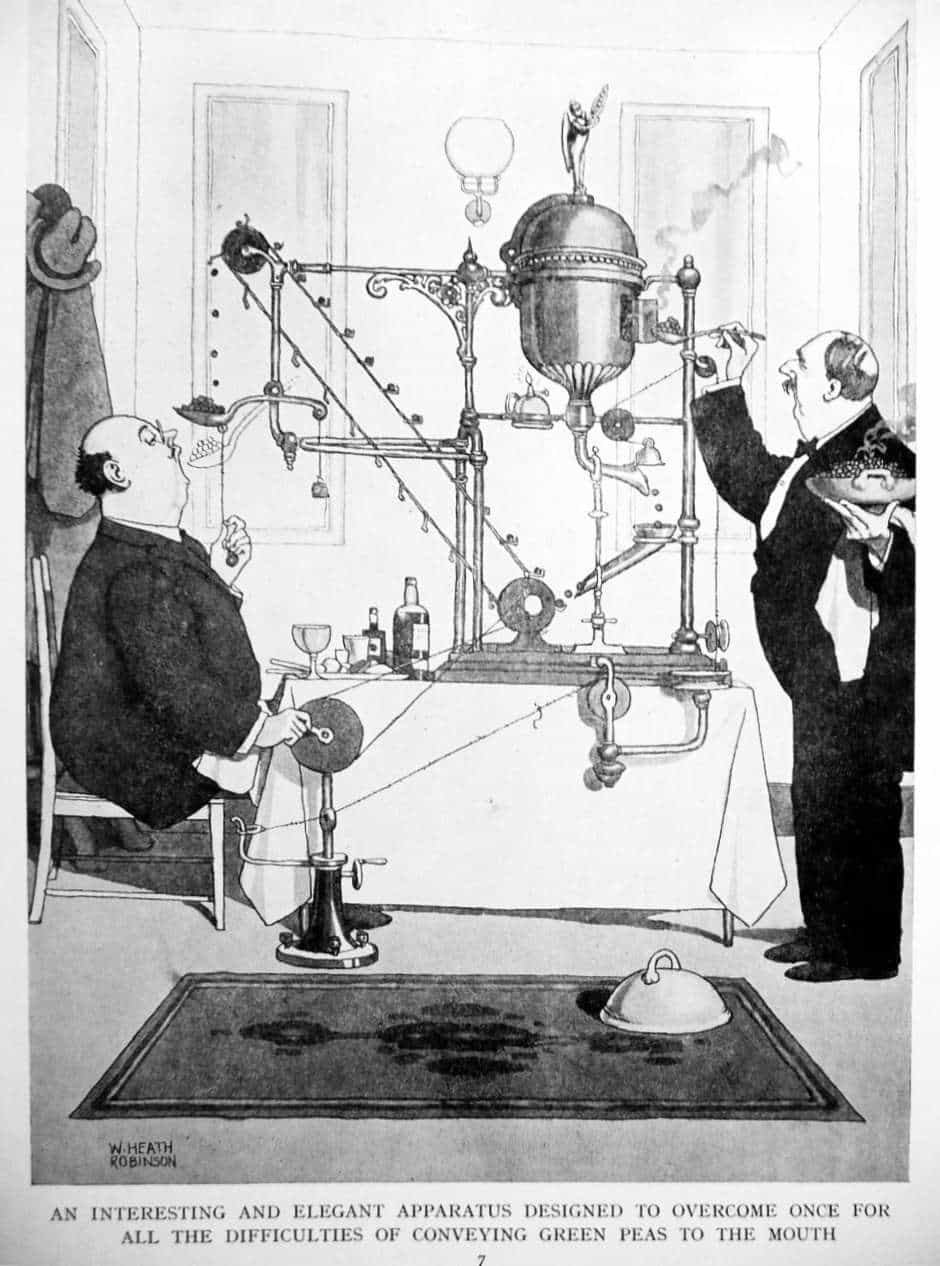

Butlers in the 1950s were effeminate figures of fun, but were in another sense impressive figures. Kazuo Ishiguro captured this extremely well in The Remains of the Day: Butlers were almost gentlemen but not quite. The whole servant and master relationship in this period featured a minutely calibrated vocabulary about class. Only an initiate could speak in it. To the untutored eye, this butler looks like a gent. But to the people in the know, a gentleman would never wear a striped trouser and a dark jacket at the same time. The butler isn’t quite.

Butlers adopted a mode of speaking — what we might call ‘butler-ese’. Ishiguro captures this voice very well in the novel. It may seem a strange way to narrate a book, but if you ever read butlers’ memoirs, they all write using this same language. It’s almost as if there were some butler school which taught it. Ishiguro beautifully captured the voice — ponderous and lugubrious. This is more evident in the book than in the film, of course.

The young doctor then asks Stevens if he ever knew Lord Darlington — now remembered as an almost-war criminal — Stevens denies ever having worked for the man. Eventually the young man expresses such negative feelings towards Lord Darlington, the loyal Mr Stevens owns that he did work for Lord Darlington, and that he always found him to be the utmost gentleman.

Standing in for the widely shared views of a modern audience, the young man cannot understand how an older manservant such as Mr Stevens could remain loyal to a traitor, and presses him: Didn’t you know he was betraying secrets to Nazis? How do you feel about having dedicated your life to such an individual?

MR STEVENS REPRESSES ANY FEELINGS FOR MISS KENTON, SO SHE MARRIES ANOTHER MAN

But Mr Stevens has spent his entire life avoiding any opinions and desires of his own. He refuses to admit to having any opinion at all, instead focusing on the man he saw in front of him, which was a kind man who fed him, housed him, and employed Stevens’ father in his old age.

LORD DARLINGTON is A SILLY, MISGUIDED MAN WITH GOOD INTENTIONS AND DECEPTIVELY NICE MANNERS

But via a series of flashbacks, the readers and viewers can see that Lord Darlington may have had gentlemanly manners, but he was not the good, kind person Stevens believed him to be. Darlington held forth on matters he knew nothing about, and this over-confidence due to his class allowed Darlington to be manipulated by Nazis in mysterious ways.

Most tellingly of Darlington’s weak character, Darlington accepts two Jewish refugees as servants in his house.

But as soon as he realises his gentleman ‘friends’ (manipulating Nazis) won’t abide Jews, no matter how hard-working, Darlington sends them packing. The man understands full well that to send them away would mean likely death, but when it all boils down, the false friendship with Nazis is more important to him than caring for his own staff. Mr Stevens fails to connect that Darlington would do the same to him if he were a Jew.

JEWISH SERVANTS IN THE WARTIME ERA

Before talking about Jewish domestics in England, we need to go back in time and talk about why fewer English people were going into service.

By the 20th century, a lord and his servants were a pantomime of an ancient feudal community which stretched back to the Middle Ages. Victorian and Edwardian households were a re-casting of the rollicking entourage you’d get in a Medieval feudal household.

Right up to the 18th century, these entourages of servants were almost entirely men. Until then, woman domestics were the exception. (You might find women doing specific jobs such as working in the dairy.) Woman entering domestic service in large numbers was a direct response to industrialisation, which created brand new classes (the middle), and therefore much class anxiety.

Aristocrats wanted to restore a feudal social hierarchy. They tried to fix it by having many servants in uniforms behind a green baize door. Although the humans themselves weren’t necessarily visible, everybody knew that a large household could not run without a massive entourage, so this was a very visible pantomime of the old feudal order. These domestics were a necessary part of the pretence that these old households had the deepest roots, locked forever in a chivalric ideal.

Mr Stevens went into service as a young man around the Edwardian period. By this time, domestics were largely girls and women, ruled by a male butler. In 1901 there were approximately 20 women to one male servant. By this time, the male servant is the preserve of the grander households. Less wealthy households were not able to afford to pay a man.

Even by the Edwardian era, the Great Country Estates were already on the decline. They had already peaked and were struggling to hold onto that lifestyle. Employment of many servants was how you showed your peers that you were hanging on. Women were beginning to not want to go into service because job opportunities were expanding for women.

The superfluity was the point. If there’s not enough work to go round, strange titles would be invented for excess domestics. There are many stories which seem to exemplify outrageous laziness on the part of the wealthy class who employed them. Rather than lift a finger to do a simple task with an item right beside them, they will ring for someone to do it. Winston Churchill came of age in this era, and is remembered partly for being absolutely without the most basic of life skills, unable to function without the aid of many servants and helpers all around him. He required people to help dress him. By the 1950s there were few of his class around.

“I can boil an egg. I’ve seen it done.”

Lack of practical skills is the hallmark of the gentleman. Gentlemen do not soil their hands with anything useful. Gentlemen are all about the riches of the mind.

Before the 1920s the ‘lady help’ was a washed-up spinster type. That was the prevailing archetype, who everyone imagined when they thought of ‘lady help’. But by the 1920s, the lady help was a brilliant woman who could turn her hand to everything. These women boasted their talents, sometimes highly specific and idiosyncratic. This is because middle class women were entering the workforce for the first time. These women had specific skills e.g. dog-walking and flower arranging or playing piano, talking about literature, event planning for dinner parties.

Over the course of 19th century domestic labour became increasingly feminised. That change happened because, after industrialisation, there was less work on the land for women who would formerly be part of a farming household. During the Edwardian era (the era of Downton Abbey) there were 1.5 million servants in Britain, the single largest occupational group for women. (Altogether, 4 million British women were in the paid workforce.)

Importantly, when understanding Mr Stevens, there was a slight change in the prevailing attitudes towards men in service. Whenever a job becomes feminised, the men who work in it are also feminised. So any men still working as domestics were regarded slightly emasculated figures. They were joke figures: lackeys and flunkies, someone’s obvious subordinate in a conservative system by now despised by their fellow working class.

This explains why (straight) men no longer flocked to domestic service. But why was the job unattractive for English women, as well?

The average starting age of a girl in service was 14, just two years after their parents were allowed to pull them out of education. At 12, 13, 14 these girls wouldn’t have had any real career options. They would go into service as a ‘tweenie’. Poor working class families were often keen for their daughters to ‘get their feet under the table’ of a big house. There, these children were relatively well looked after compared to life on the outside in a cold house with too little food. In the best situations she would be warmer and better fed, surrounded by nicer furniture and surroundings.

Audiences of shows like Downton Abbey are left with the sense that domestics entered when young, spent their whole lives in the big house then retired to arms houses, with lives completely framed by the estate. But in exchange, domestics sacrificed their freedom. Rules regarding ‘followers’ were strict. If you did marry you were sacked. Servants belonged to a sort of unmarried priestly caste looking after the inner sanctum of the family.

Parents who sent their girls into service may have hoped they would still marry, however, and provide grandchildren. For young women, the chance of getting married if they worked in a big house were greater than if they worked in a middle class house because there were more male servants in the big houses, and even more if you could snag a visiting male servant. (I’d suggest there were fewer straight male servants than there were male servants, partly due to the feminisation of the work.)

But before they could contemplate escape by marriage, these tiny maids were regularly so malnourished that they would collapse under the weight of carrying pails of water up and down stairs. These girls really were children.

When you start in service very early you might never even meet your employers, who are nonetheless in loco parentis. You are under the care (supervision) of the butler and ‘the household’. A prevailing mantra of the time: “Servants, like birds, must be caught when young.” These girls would leave their parents and work long hours which were never specified, never limited.

This partly explains why factory work ended up more popular than service. At least with factory work there’s a clocking off. Tweenies were up early to light all the fires. This was back-breaking work in a big house. They heated the water for the baths and prepared the range for breakfast. In winter this work was freezing cold.

They worked until they were told their work was over. If you were a kitchen maid you’d be working very late because of all the washing up. As a maid you could go months or years without laying eyes on the master or mistress of the house. In some houses, if you did catch sight of them, you were required to turn your face to the wall. (The prospect of catching the eyes of their domestics was the very thing which made some masters refuse electricity for decades after it became available to them. They didn’t want their houses lit up. Many preferred their staff to remain in the shadows.)

The first world war was a great period of crisis for the old great houses. This was the first nail in the coffin, but economic depression meant there was such deprivation that people had to go (back) into service, but they were no longer going back with the same sense that service was their inevitable place in life. Working class people no longer felt that their place in life was divinely ordained. These domestics brought with them a whole new set of workplace expectations. In contrast, the Victorians would literally display signs which said, “Know your place.” By the late 20th century domestics no longer felt that, with the exception of a few ageing examples such as Mr Stevens.

The Daily Mail complained at this time about girls in the streets ‘all dressed up and nowhere important to go’, which bemoaned the reality that these girls were walking freely about in public when they should have been in the kitchen, working as servants for their betters. These young women had experienced a small taste of self-actualisation by working in factories and so on during the war, and now fully understood the awfully restrictive requirements of domestic life.

This is where Jewish domestics come in.

These gaps in service were filled in the 1930s by Jewish immigrants. Immigrant labour had often come from very comfortable Viennese flats, and landed in these huge, cold, uncomfortable Victorian villas doing menial work all day, even if they were well-educated. They had probably been using toasters for three decades already, but now they were expected to make use of a toasting fork.

They ate meagre meals of herrings for lunch, in accordance with the English upper-class cult of ‘eking things out’ and miserable frugality. Some of them had lived in staffed houses themselves, as a member of the upstairs class. Older men who suddenly found themselves in service in their fifties after enjoying a life as a professional man would have found this turn of events a major life hurdle. It is unimaginably humiliating to go from having a servant to being one.

TECHNOLOGY IN THE COUNTRY HOUSE BY MARILYN PALMER

For the aristocracy in Britain and Ireland, country house living was dependent upon the labors of men and women who performed innumerable chores involving cooking, cleaning, and the basic operation of the household. In the 18th century, however, the Industrial Revolution began to change this by introducing new devices and systems that simplified a wide range of duties.

In Technology in the Country House (Historic England Publishing, 2016; distributed in the U.S. by University of Chicago Press) Marilyn Palmer and Ian West detail the extensive range of innovations adopted by country house owners from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries and their impact on the operations of their homes and estates. As West explains in this podcast, though many of these innovations were labor-saving devices, often they required not fewer servants, but ones trained in the new tasks of how to operate and maintain them. Their introduction was often undertaken by owners out of a personal interest in the innovations of the age, or who adopted them because of their fashionability–motives which, as West explains, provide useful examples of how technology is introduced into society generally both then and today.

interview at New Books Network

Compare and contrast with the culture this replaced:

Consumption and the Country House by jon stobart and mark rothery

During the 18th century English country houses served an important function in their society as stages for the display of the status and power of the landed aristocracy. As Jon Stobart and Mark Rothery demonstrate in Consumption and the Country House (Oxford University Press, 2016), though, they also played a revealing role as centers of consumption. Using three aristocratic families from the Midlands as case studies, Stobart and Rothery survey their patterns of spending over several generations, revealing the factors that shaped them. This spending, they argue, was not constant but instead saw fluctuations that coincided with life events, such as deaths and inheritances. Such dramatic changes were followed by the acquisition of goods that often were then used to create venues for these families to display their elite identity, with pursuit of the fashionable often tempered by issues of taste, rank and lineage. Stobart and Rothery’s analysis is not confined to large expenditures, however, as they also examine the more mundane spending necessary to keep these large households functioning and the gendered spheres that often defined the roles played by husband and wife in purchasing goods and services. Their analysis of these activities helps to refine our understanding of country houses, demonstrating how they were not the static exhibits we know today but fluid environments in which families left an ever-changing imprint.

interview at New Books Network

(You may also like to see what was going on in Irish country houses during the Georgian era.)

The record shows that Quaker families were much kinder to their immigrant servants than other English families in this era, who were utilising this new cheap labour perhaps for the first time, and who never spoke to their servants, nor seemed to know how to treat them. Perhaps the most uncomfortable relationship of all is when one class is served by a class of people of basically the same social rank, education, dress and manners.

Who is Reginald Cardinal in The Remains of the Day?

Played by Hugh Grant, Reginald Cardinal is name of Lord Darlington’s close friend’s son. The young man is about to be married and Lord Darlington has stepped into a sort of fatherly role after Reginald Cardinal’s own father died. Cardinal works as a journalist. He realises his uncle is being used as a pawn by Nazis and eventually tries to run this idea past Stevens, knowing that Stevens would have been in the room when suspicious wheelings-and-dealings were happening. Perhaps Stevens can shed some light. No luck. Stevens has no intelligence for him.

Like his uncle, Reginald Cardinal is a gentle-hearted man of good manners but, unlike his uncle, Reginald is of a younger generation and less easily duped. He is a working man, not a gentleman, which gives him a different perspective on life, especially since he is a journalist, privy to the details and reality of war.

He feels he and Stevens are simpatico because Stevens once (poorly) attempted to engage Reginald in discussion about the birds and the bees. (Reginald figured Stevens was attempting to engage him in a discussion about hunting and fishing.) Reginald no doubt finds Stevens a bit eccentric, but is sufficiently proximal to the aristocratic class that he also understands him, on some level.

Reginald Cardinal soon experiences the war up close and personal. He is killed on the battlefield in Belgium.

WHAT MOTIVATES LORD DARLINGTON TO BE A NAZI COLLABORATING DUPE?

Lord Darlington’s backstory is that he lost a very close friend to suicide after the last world war. (Herr Bremann.)

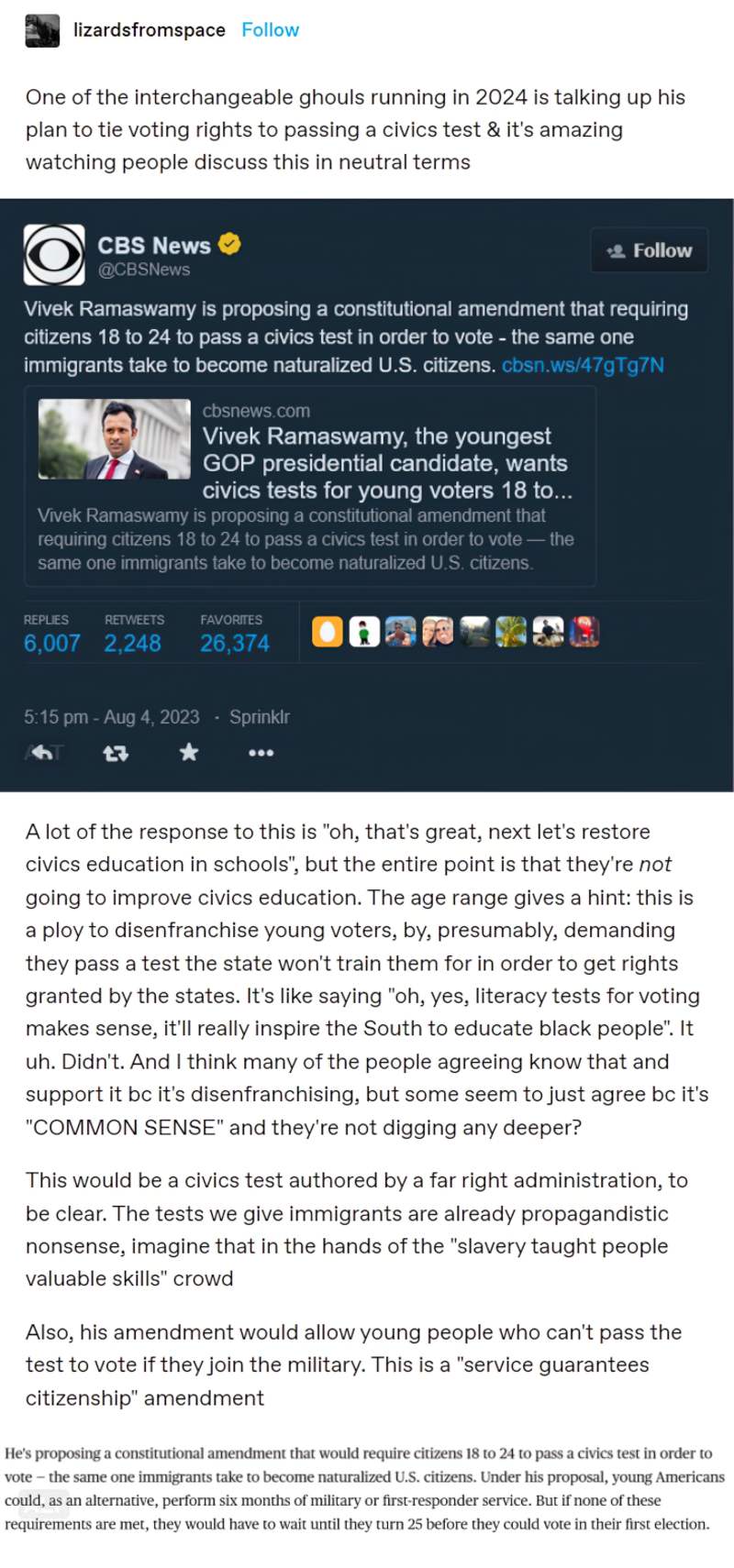

Note that the “debate” around whether poor people should get a vote continues on to this day. In the USA, for instance, in 2023 Vivek Ramaswamy has proposed a constitutional amendment requiring young citizens to pass a civics test before being allowed to vote.

In October 2023, the ‘funny guy’ on America’s Fox News, Greg Gutfeld, said that “elections don’t work” and “society is in peril and chaos because our elections don’t matter” while urging for a new American civil war.

Back to The Remains of the Day. During his own visits to Germany, Lord Darlington feels badly for the Germans, who have been left in dire economic straits due to the harsh terms outlined in the Treaty of Versailles. His German friend did not survive it. This treaty required that Germany pay financial reparations, disarm, lose territory, and give up all of its overseas colonies. The treaty also called for the creation of the League of Nations.

Basically, Darlington feels England should have more sympathy for Germans, and this opens him up to the persuasion of Nazis, personified by Herr Ribbentrop, who are using this aristocrat to further their own agenda in Britain. (Stevens does not himself have access to the exact details of that, so details are handwaved in the book.) He sees international relations like a game between expensive rival private schools. The boys have bashed it out, now let’s all shake hands and get on with things, what.

Darlington suffers from a kind of inverse psychic numbing. Most people are able to turn off painful empathy when we hear thousands of people have been killed in a massive earthquake (“psychic numbing“), but bring two affected individuals to our own home and we’ll feel the greatest empathy.

THE OLDER MR STEVENS DIES OF OLD AGE

The older Mr Stevens, Stevens’ father, is in his seventies, in ill-health and no longer up to the work expected of servants, even with his demotion of under butler.

When the elder Mr Stevens dies, the younger Mr Stevens represses his grief entirely, which tells us just how adept he is at repressing his emotions.

“Oh yes, just tired.”

The real story here is that of a man destroyed by the ideas upon which he has built his life. Stevens is much preoccupied by “greatness”, which, for him, means something very like restraint. The greatness of the British landscape lies, he believes, in its lack of the “unseemly demonstrativeness” of African and American scenery. It was his father, also a butler, who epitomised this idea of greatness; yet it was just this notion which stood between father and son, breeding deep resentments and an inarticulacy of the emotions that destroyed their love.

Salman Rushdie: rereading The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

STEVENS SUPPRESSES REGRET AT A LIFE WASTED

The story ducks and dives between the past and the present. Returning to the 1950s, the younger Stevens is himself in his late middle-age, England has changed and Mr Stevens is doggedly a man from an earlier time. It’s in his best interests to maintain the ruse, even to himself, that he never wanted anyone or anything for himself, and that he has lived a good life despite serving a Nazi collaborator who himself had regrets at the end. Stevens had believed that to serve a great man is a life well lived, but what if that ‘great man’ turns out to be not so great after all?

STEVENS REUNITES WITH MRS BENN

At the end of his road trip Mr Stevens successfully meets up with Miss Kenton, who he must remember is now called Mrs Benn, who previously informed him by letter that she is thinking of going back into service. (Her marriage has been unhappy and she needs to earn a living again.) But she has just now received news that her daughter will be having a baby, which means she must stay local, to help with the grandchild.

A TRAGIC ENDING

We feel Mr Stevens’ disappointment as he realises he must return to Darlington Manor alone, and without the great love of his life. If he had allowed himself to fall in love twenty years earlier, he would not be spending the rest of his life in what must feel like interminable loneliness, surrounded by new people he has known for a very short time.

WHAT HAPPENS AT THE END OF THE REMAINS OF THE DAY?

Mr Stevens returns to Darlington Hall, where he will begin work with a housekeeper who used to be a school matron, a woman he doesn’t know.

The film closes with the imagery of a pigeon trapped in one of the rooms at Darlington Hall. Stevens is charged with the task of setting it free, but, tellingly, is unable to catch it. The younger (freer) Mr Farraday (a.k.a. the older Lewis) catches it instead and after the pigeon tries to escape via the skylight, is eventually set free from the cupped hands of Stevens’ new employer. An aerial view of Darlington Hall fades into the distance as the pigeon flies away. Unlike Stevens, the pigeon has found freedom.

We try so hard to hide everything we’re really feeling from those who probably need to know our true feelings the most.

Colleen Hoover, Maybe Someday

Irony in The Remains of the Day

- Irony = a meaningful or significant gap between expectation and outcome.

- Irony = incongruities from the world of opposites.

- Irony = the difference between what is understood and what is meant.

Some ironies only exist in the mind of the audience. Others occur in the mind of the fictional character. Irony can occur on many different levels.

Presentation irony

the gap between the audience’s expectations and the outcome in the story.

Although Nicholas Sparks et al. have made a career out of love tragedies, the audience of The Remains of the Day will be expecting a love story between Mr Stevens and Miss Kenton. If not a love story, some kind of acknowledgement of love from Mr. Stevens, suggesting he’s experienced character growth.

The audience does not get that, which makes this story a tragedy.

DRAMATIC IRONY

Dramatic irony describes audience knowledge versus characters’ knowledge. In a good story, every single scene has at least a little dramatic irony. Hitchcock and Spielberg are well-known for their ability to know what the audience is thinking at any given moment, and then work with it. To employ dramatic irony successfully, the storyteller must understand their audience.

Kazuo Ishiguro understood that contemporary readers would want Mr. Stevens to change along with the times. The audience understands that Mr. Stevens would have a good chance at happiness (thereby making Miss Kenton happy) if he were to let himself acknowledge and extend his feelings for her.

The irony is between the audience and Mr Stevens. We understand the feelings are there; Mr Stevens refuses to admit them.

The main point of The Remains of the Day is to illuminate a class of people who were never permitted their own needs and desires — a type of person who we no longer meet in the modern world, because no self-actualised individual would put up with such a life. Also, automatic respect for the aristocratic class is on its way out.

Why is Stevens an unreliable narrator?

W.G. Sebald once said to me, “I think that fiction writing which does not acknowledge the uncertainty of the narrator himself is a form of imposture which I find very, very difficult to take. Any form of authorial writing where the narrator sets himself up as stagehand and director and judge and executor in a text, I find somehow unacceptable. I cannot bear to read books of this kind.” Seabed continued: “If you refer to Jane Austen, you refer to a world where there were set standards of propriety which were accepted by everyone. Given that you have a world where the rules are clear and where one knows where trespassing begins, then I think it is legitimate, within that context, to be a narrator who knows what the rules are and who knows the answers to certain questions. But I think these certainties have been taken from us by the course of history, and that we do have to acknowledge our own sense of ignorance and of insufficiency in these matters and therefore to try and write accordingly.

For Sebald, and for many writers like him, standard third-person omniscient narration is a kind of antique cheat. But both sides of the division have been caricatured. […]

Even the apparently unreliable narrator is more often than not reliably unreliable. Think of Kazuo Ishiguro’s butler in The Remains of the Day, or of Bertie Wooster, or even of Humbert Humbert. We know that the narrator is being unreliable because the author is alerting us, through reliable manipulation, to that narrator’s vulnerability. A process of authorial flagging is going on; the novel teaches us how to read its narrator.

James Wood, How Fiction Works

Stevens is a loyal, upstanding citizen and his reliability comes from the fact that he has been suppressing his emotions and his self-hood for so long that he has never learned to know himself. He has no real desires of his own because he has never been allowed to want anything. So when Stevens shows readers tepid reactions towards Miss Kenton, it’s likely he would feel far more strongly were he to allow such feelings to emerge from deep inside himself.

Likewise, at the end he was very much hoping Mrs Benn would return to the castle to work with him once again, so the two of them could live out their final years with a companionable mutual understanding, but when he learns that Mrs Benn won’t be coming back, he does not permit himself to express the major disappointment we know he must be experiencing privately.

Stephens sounds deceptively neutral — a deception which works on himself. To a modern audience, he sounds remarkably like Siri or any other similar personal assistant in the early 2020s.

Butler as Automaton:

My good man, I have a question for you. Do you suppose the debt situation

regarding America factors significantly in the present low levels of trade? Or is this a red herring, and the abandonment of the gold standard is the cause of the problem?I’m sorry, sir, but I am unable to be of assistance in this matter.

Oh, dear. What a pity. Perhaps you’d help us on another matter. Do you think Europe’s currency problem would be alleviated by an arms agreement between the French and the Bolsheviks?

I’m sorry, sir, but I’m unable to be of assistance in this matter.

Very well, that’ll be all.

One moment, Darlington, I have another question to put to our good man here. My good fellow, do you share our opinion that M. Daladier’s recent speech on North Africa was simply a ruse to scupper the nationalist fringe

of his own domestic party?I’m sorry, sir. I am unable to help in any of these matters.

You see, our good man here is “unable to assist us in these matters”. Yet we still go along with the notion that this nation’s decisions be left to our good man here and a few millions like him. You may as well ask the Mothers’ Union to organize a war campaign.

Thank you. Thank you, sir.

You certainly proved your point.

Q.E.D., I think.

The Remains of the Day film script

But of course to avoid taking a political position is itself a political position. By doing nothing, even a butler is doing something. He is colluding with his silence.

All the hardest, coldest people you meet, were once as soft as water. And that’s the tragedy of living.

Iain S. Thomas

Is The Remains of the Day a Love Story?

What does Stevens regret in The Remains of the Day?

Our greatest fear should not be of failure, but of succeeding at things in life that don’t really matter.

Francis Chan (American Protestant author, teacher and preacher)

I want to be with you, it is as simple, and as complicated as that.

Charles Bukowski

Stevens does not express regret on the page. The audience must deduce. It is likely Stevens has a combination of regret, should he let his mind go there:

- He dedicated most of his working life to a man who acted very badly and against the pre-war England Mr. Stevens knows and loved.

- As head butler, Stevens is required to live a life of celibacy. He takes this literally. Yet when Mr Farraday asks Stevens to explain the birds and the bees to his nephew, about to be married, it is clear to the reader that Farraday has expected his servants to know full-well about such things. So although Mr Stevens is not permitted to live a public life of sex and romance, there’s every expectation, including from his employer, he has a private life behind the green door. (This is part of the irony — something readers understand but which Stevens, in real time, does not.) Stevens lives his whole life without love and romance when there was never any real expectation that he make such sacrifice. It seems to me that Mr Stevens was fine without romance until old age, when everyone he knew either died or moved on. Now the loneliness is about to set in. But whether he regrets not marrying Miss Kenton is another matter, as he may not be straight, for starters. (See above.)

- It’s also tempting to think that Stevens may have had a little sway on Lord Darlington himself. What if Stevens had said to Lord Darlington, “If those Jewish girls go, I go,” like Miss Kenton wanted to do. Unlike Stevens, Miss Kenton acknowledges that the only reason she didn’t go through with her ultimatum is because of fear and loneliness. As a woman, Miss Kenton was not in a position to make such an ultimatum to Lord Darlington himself, but what if Stevens had, as a fellow older man and much longer employee? Might Lord Darlington have been persuaded to at least allow the girls to stay downstairs, never seen or heard, until the war was over? A number of decent folk during WW2 made exactly that decision. What if Stevens had arranged this off his own bat? He could have been more choosey about when to be loyal to his employer, and when to do what he knew to be right.

FASCISM UNDER THE ROOF

I feel like too many people don’t recognise fascism because they think fascism will arrive selling oppression and tyranny, but if you’re part of the privileged group, fascism is selling you safety, normalcy and tradition.

@byroncclark on Twitter

As good a time as any to remind folks of the 14 properties of “ur-fascism” (described by Umberto Eco, who grew up in Italy under Mussolini, in his 1995 essay Ur-Fascism). Not all need be present for single regime to be fascist, but a Venn diagram of all fascist regimes will cover them all.

theshampyon on Tumblr

- CULT OF TRADITION. The old ways are best. The New is not worthwhile.

- REJECT MODERNISM The development of Western philosophy post-Enlightenment is seen as a descent into depravity. See also : Reject post-modernism, which is seen as an even greater descent into irrationality.

- ACTION FOR ACTION’S SAKE. Action is to be taken without reflection or introspection – that’s for weaklings and degenerates. Often seen in a derision of “intellectual elites”.

- DISAGREEMENT IS TREASON. Analytical criticism cannot be allowed. A pantomime of discourse may be allowed, but only within the accepted framework and only if reaching the foregone conclusion.

- FEAR OF DIFFERENCE. Outsiders are your enemy. Those who are different are evil and want to corrupt you and destroy all you hold dear.

- APPEAL TO A FRUSTRATED MIDDLE CLASS Capitalising on genuine frustrations by pointing them toward convenient scapegoats. Real concerns used a recruiting tools.

- OBSESSION WITH A PLOT. There is a conspiracy run by THEM. You are besieged by THEM. THEY are behind all your ills. THEY are working in the shadows to enslave and destroy you.

- THE ENEMY IS BOTH STRONG AND WEAK. When rhetorically convenient, THEY are all-powerful. When rhetorically convenient, THEY are feeble, stupid, weak. The rhetorical focus shifts regardless of self-contradiction, because all that matters is positioning the enemy where the speaker’s goal requires them to be at any given moment.

- PACIFISM IS THE ENEMY. LIFE IS ETERNAL WAR. There must always be an enemy to fight. When that enemy is defeated, another must be found. When they cannot be found, they must be created, even from within. There is always the promise of a Final Solution bringing Ultimate Triumph, but it can never be achieved.

- CONTEMPT FOR THE WEAK. Elitism disguised as populism. Everyone of US is superior to THEM, cockroaches and drains on society that they are. But people are sheep who require strong leaders, who are by their nature superior to others.

- EVERYONE IS TAUGHT TO BE THE HERO. A CULT OF DEATH. Where in myth the hero is exceptional, in fascism everyone must be the hero. They crave heroic death, the reward for heroic life. In seeking it, they send others to die. (See also: Militarism).

- MACHISMO. Disdain for women and femininity. Intolerance of non-standard sexuality and gender expression.

- SELECTIVE POPULISM. The People are viewed as a monolith with a single will, as interpreted (in reality, determined) by the leaders. Democratic institutions are viewed as illegitimate because they run counter to the narrative of the existence of a single Voice Of The People.

- NEWSPEAK. Vocabulary cannot expand. If anything, it must shrink. Variation and nuance in dialogue means variation and nuance in thought. This cannot be allowed. Therefore categories must be binary. Definitions are simple and limited. If it cannot be boiled down into snappy catchphrase it does not exist.

What does the pigeon symbolize in The Remains of the Day?

At the end of the movie, Stevens is back in his familiar environs and a pigeon enters the room. Stevens is charged with the task of shooing it out. As the film ends, we see a receding aerial view of the castle, supposedly from the pigeon’s point of view. (These days filming crew would make use of a drone; in the 1990s they would have used a light aircraft.)

It’s less important that the trapped creature is a pigeon and more important that it is a bird.

Birds represent freedom, flight, the soaring spirit. To attain its freedom, a bird must leave the nest (the old house) and find its place in the world (the new house). When Stevens lets the bird out and we see the house from the bird’s eyes, this creates a juxtaposition for the audience: The bird is free, but Stevens is not.

For Stevens, this story is a love tragedy. He’ll spend the rest of his days in this house, suppressing his desires in service of a way of life he no longer truly believes in, partly because the culture has changed around him, and he can no longer wall himself off from modernity.

Flight (and thereby birds) can also symbolise some kind of disappearance, or the loss of something precious. As Frida Kahlo once wrote:

Nothing is absolute.

Frida Kahlo

Everything changes,

everything moves,

everything revolves,

everything flies and

goes away.

The world has changed around Mr. Stevens, yet here he is, trying to be the exact same man, in an England which we will never see again.

Is it important to the symbolism that the bird is a pigeon? The pigeon was an excellent choice to convey this symbolism because:

- Pigeons were one of the first animals to be domesticated, which means we associate pigeons with the domestic sphere. (Mr Stevens is comfortable in the domestic sphere, and in few other places. He is nothing if not domesticated himself.)

- Pigeons originate from Europe, North Africa and Asia. There are five species of pigeon and dove in the UK countryside. Three of them are common – wood pigeon, collared dove and stock dove – and two are extremely rare – turtle dove and rock dove. Because of a long history with domesticated pigeons, the pigeon feels like a very English choice.

- Pigeons are effective as messengers due to their natural homing abilities. This juxtaposes against Mr Stevens, who went out with a message then came home, but he was wholly unsuccessful in delivering his message. Sure, he asked Mrs Benn to resume employment at Darlington Hall, but he did not convey the message of his love. A pigeon with a love letter strapped to its back would do a better job.

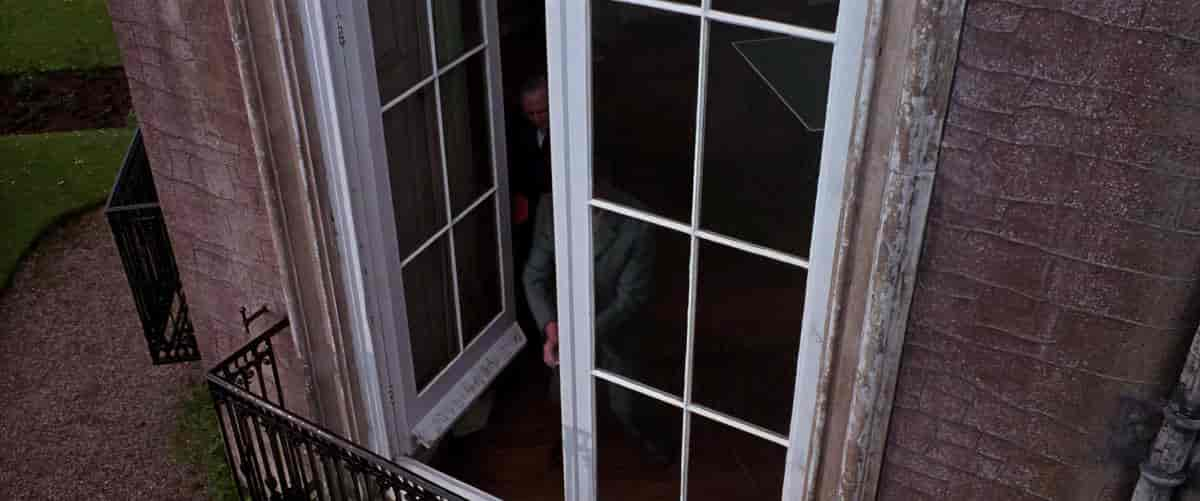

What town was The Remains of the Day filmed in?

The Remains of the Day was filmed in England, west of London, in various locations near the Welsh border and around Exeter:

- Badminton House — in Gloucestershire

- Bath

- Corsham Court — 5km west of Chippenham, Wiltshire

- Weston-Super-Mar’s Grand Pier — where Stevens and Mrs Benn spend their last few minutes together. The pavilion was destroyed in 2008 and has since had a rebuild.

- Highbury Hotel (Closed) — Blackpool

- Deer Leap — where Stevens runs out of petrol

- Hop Pole Inn (Closed) — The pub where Mr Stevens stays is the Hop Pole in Limpley Stoke, in reality nowhere near Deer Leap, but this is where Mr Stevens spends the night after his car runs out of petrol

- Dyrham Park — near the village of Dyrham in South Gloucestershire

- Powderham Castle — about 10km south of the city of Exeter

- The George Inn — Norton St. Phillip, Somerset.

- The Royal Hotel — 1 South Parade, Weston-super-Mare BS23 1JP

- Winter Gardens — the setting for Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson’s afternoon tea. Royal Parade, Weston-super-Mare, BS23 1AJ

GPS co-ordinates and a map are here.

Is there a real Darlington Hall?

No, there’s no Darlington Hall. The film was shot in four different houses/castles/manors in Southwest England.

THE FOUR HOUSES IN REMAINS OF THE DAY

For photos see the beautiful post at the SmallRooms website.

DYRHAM PARK: THE OUTSIDE

The outside of the Remains of the Day castle is Dyrham Park, a baroque style country house near the village of Dyrham in South Gloucestershire. It is surrounded by an ancient deer park, which formerly had a manor mentioned in the Domesday Book (1086).

The house is been owned by the National Trust since 1961, but was built for an English diplomat and Whig politician during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, when gentlemen really did control the politics of the country. Dyrham Park has unfortunate connections to slave-owning.

During the second world war, this house was actually used for child evacuees, rented at the time by Anne, Baroness Islington, widow of a former Governor of New Zealand. Since The Remains of the Day was filmed there, the house has undergone renovations (in 2015) and now has a whole new roof.

As well as The Remains of the Day, you’ll also see this house as a filming location in Merchant Ivory (1993), for outdoor and garden scenes for Wives and Daughters (1999) and also in the opening title sequence of Australia (2008). Two years later the “Night Terrors” episode of Doctor Who, sixth series, was filmed there. More recently, The Crimson Field (2014) and Sanditon (2019). In Poldark, Dyrham Park is the home of George Warleggan.

BADMINTON HOUSE: KITCHEN AND SERVANT AREAS

Film crew could only utilise Badminton House for the kitchen scenes, service corridor and servant areas (including Mr Stevens’ parlour) because these were the only areas not set up for tourists. The Chinoiserie decorated bedroom is also from Badminton House. We briefly see maids dealing with bed linen on its canopy bed.

The game of badminton is named after this estate.

CORSHAM COURT: VARIOUS ROOMS

Corsham is about 5km west of Chippenham, Wiltshire. This home is owned by the Methuen family, currently on the eighth generation of Methuens to live there. The present house was built in 1582. The estate was owned by royals until the reign of Elizabeth the first.

Various rooms were used in the shooting, though they were altered by the set designers to the point where they’re difficult to recognise. The dining room where the men met to discuss politics was at Corsham Court.

Corsham Court’s Picture Gallery is that red room with many gold-framed paintings, where Lord Darlington hosted a large gathering of men.

This castle was also used as a filming location for Barry Lyndon (1975) by Stanley Kubrick, based on a 1844 novel by William Thackeray.

POWdERHAM CASTLE: STAIRCASE AND LIBRARY

The oldest part of this building was built in the very early 1400s.

Powderham Castle is better described as a ‘fortified manor house’. It has never had a keep and a moat, which a castle technically requires. It has got the curtain wall, however (a defensive wall). Still, Powderham Castle been called a castle for a few hundred years now.

Find it about 10km south of the city of Exeter and about a quarter mile north-east of Kenton village (coincidentally the maiden name of Mrs Benn).

This house’s state bed was used, but not in its regular bedroom. Those beautiful blue walls around the staircase were shot at Powderham Castle, as was ‘Lord Darlington’s’ library (the Second Library of Powderham). But some of the library scenes were actually shot in the library of Corsham Court. The billiards room is also at Powderham Castle.

This house used to be a wedding location, but the castle’s licence was revoked in 2009 due to the homophobia of Hugh Courtenay, 18th Earl of Devon, who refused to let gay people marry there.

The comedy Churchill: The Hollywood Years was also filmed at Powderham Castle.

Who is Mr Lewis in The Remains of the Day?

The first thing to note: No, it’s not your prosopagnosia playing up. You may think so, if you’ve read the book before seeing the film.

In the film adaptation, two separate American characters are merged into one. Mr Lewis returns to purchase Darlington Hall. In the book, the American who purchases Darlington Hall is a different character called Mr Farraday.

The character of Congressman Jack Lewis in the film is a composite of two separate American characters in Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel: Senator Lewis (who attends the pre-WW2 conference in Darlington Hall), and Mr Farraday, who succeeds Lord Darlington as master of Darlington Hall.

The Remains of the Day, Wikipedia

In both the book and the film, Mr Lewis is an American gentleman who visits Darlington Hall for the March 1923 conference. In some ways he prefigures the American Farraday (from the book) who will eventually buy Darlington Hall in 1958. He is congenial and gentlemanly, but unlike the English gentlemen in attendance, he understands that gentlemen should steer clear of politics because they know nothing about war. He makes a speech to that effect and gets the Englishmen off side.

As a character in the story, the role of Mr Lewis is to show the audience that Lord Darlington doesn’t know what he’s talking about, and that his political influence is dangerous. His speech sets us up to expect and understand Lord Darlington’s downfall.

Foreshadowing in The Remains of the Day

For a description of foreshadowing, see this post. Basically, foreshadowing works at the level of metaphor. So let’s talk about metaphor in The Remains of the Day.

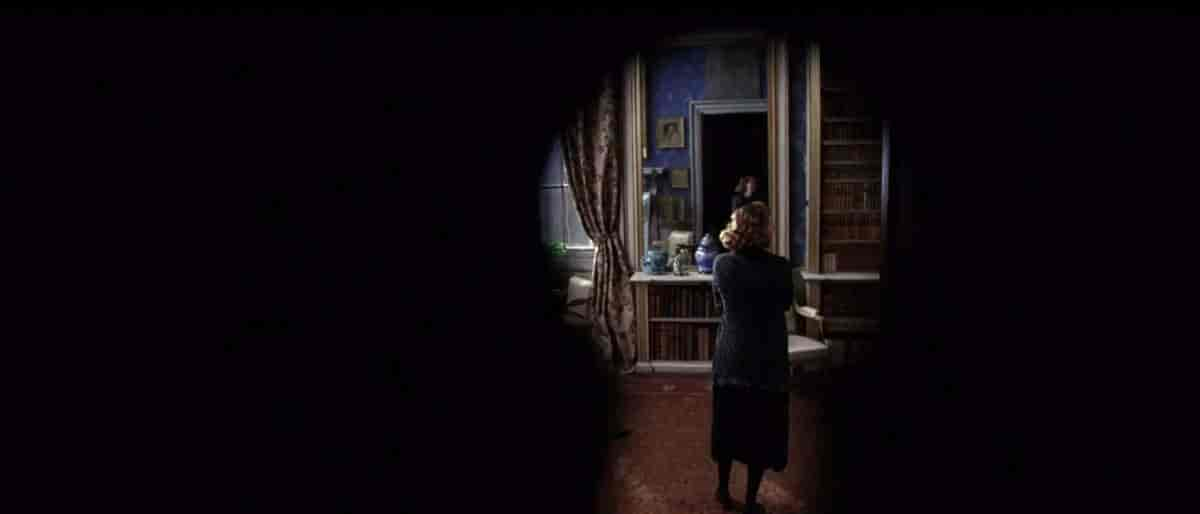

VISUAL METAPHORS OF DISTANCE AND NARROWING

All of these images work at a metaphorical level, too, showing the audience that there are ‘other parts of the picture’ that Mr Stevens chooses not to see. His is a narrow world view, and he chooses to live like this. He could so easily open those doors. Yet he doesn’t.

THE METAPHOR OF DOWNFALL

DYING OF THE LIGHT

Lights work at a symbolic level in many stories, including in this one. When Mrs Benn and Stevens meet on the pier, the lights come on as they wait. This could show audiences that Steven has had a realisation: That Mrs Benn won’t be coming back to Darlington Hall after all, and he’ll be spending the night alone.

But those lights coming on also serve as ironic juxtaposition: Something in Mr Stevens just went out. He is so at odds with the world, everyone else claps at some lights coming on, and he, alone, must sit with the heaviness in his heart.

The film also gave us some beautiful sunset shots at resonant moments. The Remains of the Day, 24-hour-cycle as one human lifespan…

THE CIRCULARITY OF LIFE (OLD AGE AND ‘CLOSING IN’)

When thinking about the future, it is easy to forget to look behind you. Enter George Dyson, “a historian among futurists”, who does deep research into the history of computing to understand the trends that will bring us into the future. One of his persistent themes is taking the “digital universe” metaphor seriously. When we turned on the first computers, we created a computational universe, a universe that is now growing by 5 trillion bits of storage per second. This universe is not merely expanding–it is exploding, and we need to understand computer time as well as we understand human time.

After Stevens says goodbye to Mrs Benn forever, the film-makers make use of symbolism so subtle we probably don’t catch it at a conscious level.

Stevens returns to his car. There’s a close up on the headlight.

The headlight turns on. Note, too, that the lights on the pier came on and everyone clapped.

Off-screen, Stevens drives back to Darlington Hall, and the we are shown the curved (almost circular) banister, in that stunning and memorable blue:

Next we’re taken to the former billiards room which the new owner has modernised by replacing a billiards table for a ping-pong table.

They notice the trapped pigeon. The pigeon tries to escape on its own after being shooed out. It flies skyward to what it thinks is an exit, but which is just a skylight. The pigeon cannot escape that way after all.

Note the death imagery (seeing the light above you, going towards it…) Because Mr Stevens is getting on himself, he is unable to catch the pigeon. The younger, nimbler Mr Farraday catches the pigeon instead. It is Farraday who releases the pigeon out the window.

But it’s not just advanced age which prevents Stevens from releasing the pigeon. He is unable to become free himself. Throughout the movie, we’ve seen many shots of Mr Stevens behind windows, peering through small holes, looking at the road from behind the glass of his employer’s vehicle.

When one thinks about it, when one remembers the way Miss Kenton had repeatedly spoken to me of my father during those early days at her time in Darlington Hall, it is little wonder that the memory of that evening should have stayed with her all of these years. No doubt, she was feeling a certain sense of guilt as the two of us watched from our window my father’s figure down below. The shadows of the poplar trees had fallen across much of the lawn, but the sun was still lighting up the far corner where the grass sloped up to the summerhouse. My father could be seen standing by those four stone steps, deep in thought. A breeze was slightly disturbing his hair. Then, as we watched, he walked very slowly up the steps. At the top, he turned and came back down, a little faster. Turning once more, my father became still again for several seconds, contemplating the steps before him. Eventually, he climbed them a second time, very deliberately. This time he continued on across the grass until he had almost reached the summerhouse, then turned and came walking slowly back, his eyes never leaving the ground. In fact, I can describe his manner at that moment no better than the way Miss Kenton puts it in her letter; it was indeed ‘as though he hoped to find some precious jewel he had dropped there’.

The Remains of the Day; Mr Stevens watches his father from the window. Miss Kenton soon joins him and they watch him practise negotiating the paving stones while he imagines holding a tray..

Stevens is in the world, but one removed. He is not of the world. And now we know he’s never escaping himself. The death imagery, the escape imagery; the ending signals the audience that he will remain in this house for the rest of his life.

The circularity not only brought audiences back to the start of the film, where the story began, but reminds us in a subtle way that Stevens is entering a more vulnerable period of his life — an old age which circles back to childhood, in a way. We saw his father die in this house, and we know Stevens will also die here (except without the son by his beside). The cycle repeats.

WHAT HAPPENED TO DOMESTICS AFTER WW2?

The end of the Second World War did not mark the end of people wanting servants; it marked the end of people wanting to be servants. English houses had to start poaching them from abroad from places like Spain and Malta where there was high unemployment. What ended was the assumption that some people were born to serve, while others were born to be served.

The 1950s and 60s gave rise to the cult of the housewife. Since domestic work has always needed to be done by someone, the work itself has never gone away. Instead, what was previously paid work now became invisibilised, unpaid labour performed by housewives. Housewives, too, were rising at dawn and finishing their tasks at 10-11 p.m. The difference between the servants and the housewives: The housewives very much wanted the labour saving devices such as vacuum cleaners, washing machines and toasters. (Vacuum cleaners were given the names of mechanical housewives — Polly and Daisy etc.) Up until the 1980s, men were never expected to touch these devices. It was always the woman of the house expected to do it.

The problem of domestic labour endures in the history of feminism. We are now at a point in history where households require two equivalent fulltime incomes to afford a house, which in straight domestic partnerships requires a woman who does a full-time paid job. Unfortunately, it is still women who shoulder the bulk of the domestic work and childcare. So for many women, work hours have not decreased. Some households employ a cleaner. The number of male domestic cleaners is minuscule, showing that cleaning is still regarded as women’s work.

All of these old houses are gone now, with the exception of Buckingham Palace. Even at Buckingham Palace, (non-)jobs such as ‘footman’ have disappeared.

There are now labour laws which protect children (and adults) from exploitation.

Until after WW2, an upper class of useless rich people were for the first time required to do many basic things for themselves. It was only now that “mod-cons” became desirable. In houses with large staffs, labour-saving equipment such as toasters were suddenly purchased. These household devices proliferated in America and on the European continent, but the old wealthy houses of England actively rejected them on principle. It was a badge of honour to have servants scrubbing and polishing. The dinner parties were designed to be as complicated as possible, to show-off how many people you had behind the green baize door organising it all.