Religion is still everywhere. So, reflecting and influencing the culture in which we find them, children’s books are not secular either.

It’s interesting to interrogate the role of religion in children’s literature because children’s literature is an acculturating medium: It will introduce children to social life and history so is both educational and enjoyable.

Many of the following notes are from the Kid You Not Podcast Episode 6: Religion In Children’s Literature.

BLASPHEMY!

There Is No Dog by Meg Rosoff met with controversy for being a ‘blasphemous’ book.

A young teenage boy is god and has created the earth, and is dealing with it very badly. It’s an attempt to explain all the suffering that happens on earth – teenagers can likewise experience the pits of despair and ecstasy at another moment.

This is a ‘concept book’. The premise defines everything about the book, from the language used (pseudo-biblical, a parody of biblical language), to the characterisation. A lot of questions are raised about teenage love and the lack of spiritualism in the teenage years.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF RELIGION IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Children’s literature has very strong ties to religion. Religion is kind of the reason why children’s books were written — to indoctrinate children.Children’s publishing was originally to publish pamphlets to develop children’s fear of god.

The very first examples of children’s literature were prayer books and stories that had religious elements. The Bible was for a very very long time the only thing that children ever read (or had read to them). The cradle of children’s literature in the West is of course based on the Christian faith.

A lot of what people call their favourite books, even today, are often very religious. Little Women is one example: All the characters try and follow the Pilgrim’s Progress, a text by John Bunion which children definitely don’t read anymore. The Secret Garden (all of the Frances Hodgson Burnett books, Anne of Green Gables, Polyanna, are all Christian.

Even children from non-religious backgrounds – who are big readers – today tend to be exposed to heavily Christian works.

Picture books with Christian themes still sell well, and so they are still published, particularly around Easter and Christmas. Parents buy them. Bible stories are really good stories on their own – the nativity story is a very pleasant story. Have they been stripped of the faith? Can they now be treated as a myth or legend? The nativity story probably fits that category for many modern families.

The Lutterworth Press is an old publishing company (of 200 years) whose mission is to publish Christian texts. They published Joan’s Crusade [which my mother had as a child, and it graced my own childhood bookshelves, and I remember one very bored Sunday I actually read it].

In mainstream publishing today, when religion is mentioned in children’s literature it is to talk about religious extremism, or else the human aspect of religion, what humans create. There are books about the Sikh community in Britain, for example, but they don’t explore faith but rather the way of life that accompanies the faith. It is currently unfashionable to express devotion to god in children’s literature.

YOUNG ADULT BOOKS ABOUT RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS RATHER THAN FAITH

For a good example of this, see (Un)arranged Marriage, set in Leicester or Killing Honour, both by Bali Rai.

Popular stories about religious traditions present extremism as something that isn’t part of the faith, as something separate and malicious and which has grown from bitterness. There are very religious characters in the story but never the main character – usually the main character’s parents.

Religion is now presented as a social problem – not necessarily in a negative way – but as something to be dealt with.

More fashionable are books sometimes attack religious beliefs. (For example There Is No Dog.)

CHRISTIAN SYMBOLS IN PARANORMAL YOUNG ADULT NOVELS

Angel by L.A. Weatherly is an example of a young adult book about angels, which are Christian ideas.

Angels are all around us: beautiful, awe-inspiring, irresistible.

Ordinary mortals yearn to catch a glimpse of one of these stunning beings and thousands flock to The Church of Angels to feel their healing touch.

But what if their potent magnetism isn’t what it seems?

Willow knows she’s different from other girls. And not just because she loves tinkering around with cars.

Willow has a gift. She can look into people’s futures, know their dreams, their hopes and their regrets, just by touching them. But she has no idea where she gets this power from.Until she meets Alex…

promotional copy of Angel, book one

Alex is one of the few who know the truth about angels. He knows Willow’s secret and is on a mission to stop her.

The dark forces within Willow make her dangerous – and irresistible.

In spite of himself, Alex finds he is falling in love with his sworn enemy.

Yet the Angel series, and the Fallen series by Lauren Kate, is devoid of spirituality even though god exists as a character. He doesn’t exist in the way religious readers would understand. It can therefore sit strangely with religious readers.

Angel accuses angels of being the cause of mental illness, which is completely at odds with their significance in religion. The main plot point is that the angels create The Church Of Angels to help angels break free from humans, which is probably a metaphor for the evangelical churches in America: Meetings, huge churches, TV evangelists. The angels need these to feed on souls. The author cleverly takes all the characteristics of a cult and applies them to angels, and the Church of Angels may be the most ingenious thing about this series. Significantly, the author at no point attacks belief itself, only organised religion. Again, this speaks to the reluctance of YA authors to tackle the issues of faith and belief head-on.

Many other recent dystopian YA novels do not mention religion at all. The Hunger Games, Delirium etc. are visions of a religion free future.

RELIGION AND CHARACTER ARCS IN YOUNG ADULT NOVELS

In pretty much every story, a character goes through a character arc, from less mature to more mature. These stories are known as Bildungsromane, though click through to find out a more accurate term to apply to most YA novels., in which the main character doesn’t become fully adult.

An author’s choice of plot, setting and conflict is pretty much infinite. But the exact nature of the character arc is more predictable than it seems when we look beneath these surface differences:

Adolescent novels that deal with religion as an institution demonstrate how discursive institutions are and how inseparable religion is from adolescents’ affiliation with their parents’ identity politics. Adolescents in such novels eventually experience language determining not only their religions beliefs, but also creating competing dialogues that influence their own religious views. Moreover, such novels depict how religion influences identity politics, especially those of race, class and gender. […] All of the protagonists [in examples given by Seelinger Trites] experience some form of the (over)regulation >> unacceptable rebellion .>> repression >> acceptable rebellion >> transcendence model that typifies the domination repression model of institutional discourse common in adolescent literature.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

PHILIP PULLMAN AND ‘RELIGIOUS ATHEISM’

Philip Pullman’s series His Dark Materials is all about stories and about how they shape your existence, and how they are your passage to life after death. Pullman hated The Chronicles of Narnia and wrote his own series – Paradise Lost for children, in a way that would say to readers that they are allowed to question religious authority. A huge proportion of the American religious community hate this series. They have been denounced by the pope. These books are able to shape a child’s ideas about religion: They are critical of organised religion but very spiritual. Pullman takes away the Christian God but replaces it with the idea that there is a higher power and everything is connected.

It’s quite a fashionable statement now to say you see the world as spiritual and connected but outside clerical order. Naturally, this is reflected in children’s literature too.

Phillip Pullman describes himself as a ‘religious atheist’. His grandfather was a priest. Most books still do commit to a Christian sense of morality. [I disagree with this. I’m with Richard Dawkins on this point, that modern morality is not of the Bible but rather an evolution of culture, shared by atheists and theists alike. Morality according to the Bible is a tough world indeed. Christians do not own morality, though Lauren and Clementine do specify ‘ideas promoted by Christianity’, which is a better way of phrasing this, I feel.]

Hear a 2010 interview with Philip Pullman on Radio New Zealand, with my favourite interviewer, Kim Hill. The interview is called ‘Jesus and Christ’.

Salman Rushdie’s book for children is also an example of an author with a religious agenda.

WHAT WOULD JESUS DO?

In Harry Potter, it is not questioned that the right thing for Harry to do is to top himself. This has a Jesus ring to it. [The reason I take issue with this being a Christian thing to do is because it’s very much a part of traditional Japanese culture – the harakiri culture which is in place even today – and Japanese culture is not based on Christianity at all. The Japanese, like the British, drive their cars on the left side of the road, but saying that therefore the Japanese drive like the Brits would be erroneous – this shared culture is simply coincidence. However, perhaps it’s the case that J.K. Rowling herself is influenced by Christianity and that it has influenced her work, which is to say a slightly different thing.]

Related: See the short video from Emory University — Harry Potter: A Christ Figure

There are a lot of book in which characters are resurrected. Providence is an important part of children’s literature, as discussed in the podcast on Death in Children’s Literature. Artichoke Hearts doesn’t seem to have much to do with religion but the protagonist frequently calls on not sure who, not sure what, to help her family.

FANTASY RELIGION

On the topic of Wicked by Gregory Maguire:

Too often in fantasy religion is either distant, or too close, with gods interacting directly with characters, and characters in turn becoming far too aware of just how this fantasy universe operates, at least divinely. Here, characters cling to faith—in at least two cases, far too fiercely for their own good—without proof, allowing faith or the lack thereof to guide their actions. It allows for both atheism and fanaticism, with convincing depictions of both, odd though this seems for Oz. (Baum’s Oz had one brief reference to a church, and one Thompson book suggests that Ozites may be at least familiar with religious figures, but otherwise, Oz had been entirely secular, if filled with people with supernatural, or faked supernatural, powers and immortality.)

Tor

KIND OF RELATED

The Five Best Depictions Of God In Movies from Film School Rejects

Next is a collection of stories about life after death, interview with editor at Books For Keeps

Richard Dawkins, well-known atheist academic [my milkshake duck], wrote The Magic Of Reality to counteract all of the religious, mythical, superstitious and anti-science ideas which permeate children’s stories. Interview also at Books for Keeps.

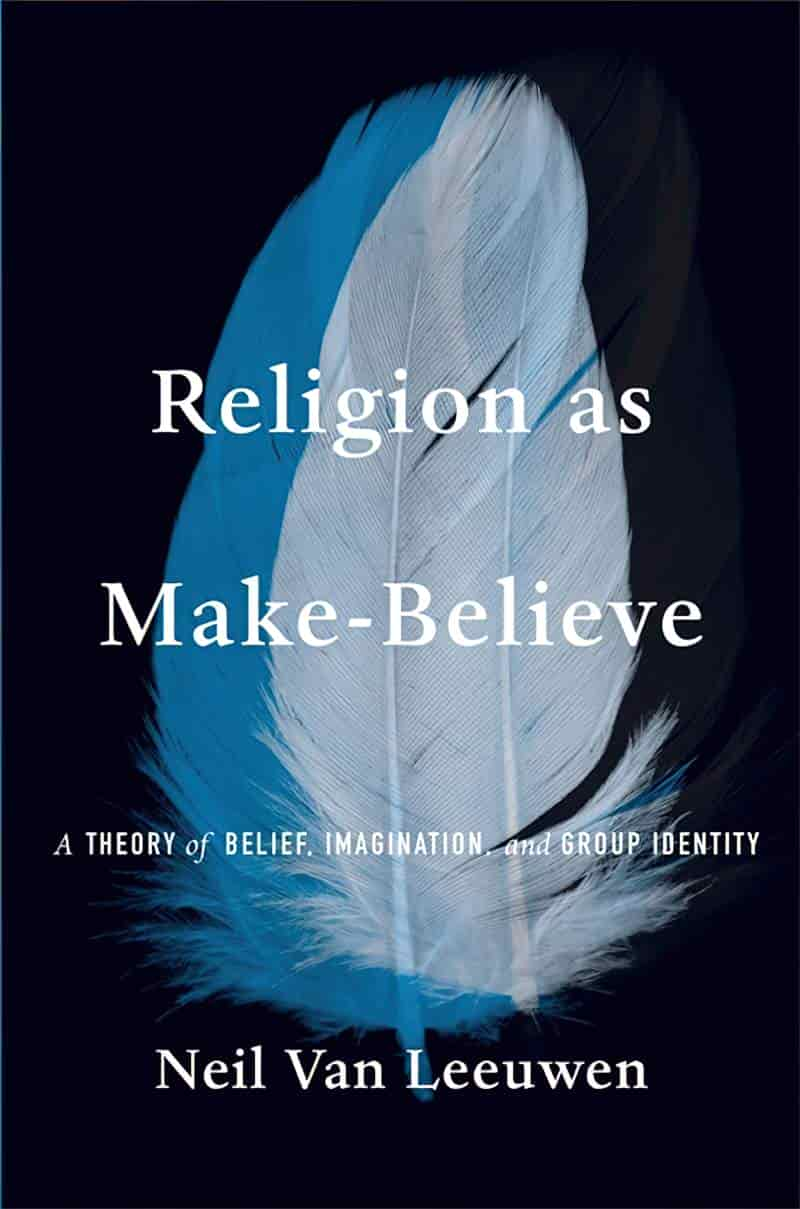

RELIGION AS MAKE-BELIEVE BY NEIL VAN LEEUWEN (11/21/2023)

To understand the nature of religious belief, we must look at how our minds process the world of imagination and make-believe.

We often assume that religious beliefs are no different in kind from ordinary factual beliefs—that believing in the existence of God or of supernatural entities that hear our prayers is akin to believing that May comes before June. Neil Van Leeuwen shows that, in fact, these two forms of belief are strikingly different. Our brains do not process religious beliefs like they do beliefs concerning mundane reality; instead, empirical findings show that religious beliefs function like the imaginings that guide make-believe play.

Van Leeuwen argues that religious belief—which he terms religious “credence”—is best understood as a form of imagination that people use to define the identity of their group and express the values they hold sacred. When a person pretends, they navigate the world by consulting two maps: the first represents mundane reality, and the second superimposes the features of the imagined world atop the first. Drawing on psychological, linguistic, and anthropological evidence, Van Leeuwen posits that religious communities operate in much the same way, consulting a factual-belief map that represents ordinary objects and events and a religious-credence map that accords these objects and events imagined sacred and supernatural significance.

It is hardly controversial to suggest that religion has a social function, but Religion as Make-Believe breaks new ground by theorizing the underlying cognitive mechanisms. Once we recognize that our minds process factual and religious beliefs in fundamentally different ways, we can gain deeper understanding of the complex individual and group psychology of religious faith.

Godless Fictions in the Eighteenth Century: A Literary History of Atheism

Although there were no self-avowed British atheists before the 1780s, authors including Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope, Sarah Fielding, Phebe Gibbes, and William Cowper worried extensively about atheism’s dystopian possibilities and routinely represented atheists as being beyond the pale of human sympathy. In Godless Fictions in the Eighteenth Century: A Literary History of Atheism (Cambridge University Press, 2020), Dr. James Bryant Reeves challenges traditional notions of secularization that equate modernity with unbelief, revealing how reactions against atheism instead helped sustain various forms of religious belief throughout the “Age of Enlightenment.” He demonstrates that hostility to unbelief likewise produced various forms of religious ecumenicalism, with authors depicting non-Christian theists from around Britain’s emerging empire as sympathetic allies in the fight against irreligion. Godless Fictions traces a literary history of atheism in eighteenth-century Britain for the first time, revealing a relationship between atheism and secularization far more fraught than has previously been supposed.

New Books Network

Header illustration: Norman Rockwell (American painter) 1894 – 1978 Walking to Church, 1953