Earlier this month I wrote a post on Teaching Kids How To Structure A Story. Earlier this week I looked closely at Mac Barnett and Jon Klassen’s Sam and Dave Dig A Hole to show how this classic story structure can be turned upside down, ironically. Today ‘s story is The Really Ugly Duckling.

The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales is a metafictional picture book from 1992, by Jon Scieska and illustrated by Lane Smith. It’s a collection of very short stories, but I’m only going to look at one. Like other tales in the book, The Really Ugly Duckling is a re-visioning of the classic fairy tale The Ugly Duckling by Hans Christian Andersen. To get the gag, the reader is meant to know the original tale, otherwise it’s not so funny.

The Really Ugly Duckling shows writers can break the rules of narrative and create surprise. In this case, Jon Scieszka omits the bit that normally comes after the Big Battle. The fancy word for this part is ‘denouement’. In seven step story structure, the denouement is the final two steps.

If you aren’t going to write the last two steps, you need a good reason, other than, ‘I got sick of this story and called it quits’. Usually, these stories with an abrupt ending aim to make the reader laugh.

There are terms to describe these kinds of stories.

- If the story ends right before the big big struggle, it’s called a Bolivian Army ending. (The name comes from classic movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. We never get to see the main characters die.)

- If someone’s been spinning a long-winded, really boring story with lots of pointless detail and then refuses to finishes it off to make you groan, it’s called a Shaggy Dog story. These stories are pretty good and hold your attention. They’re designed to disappoint.

- A Shaggy Dog story is also known as the Feghoot. A feghoot is described as a short-short story (300 words on average, although 500-word examples exist), ending in a pun or a punchline that is pretty obviously the only reason for the story’s existence. The telling detail in a Feghoot is the groan emitted by the reader/listener when he hits the punchline. A Shaggy Dog tale is more likely to be known as a Feghoot if it’s in written form.

- Related to the Shaggy Dog story is the Shaggy Frog story. Unlike the Shaggy Dog story, the Shaggy Frog story goes absolutely nowhere.

The Really Ugly Duckling is too short to be a Shaggy Dog story, and there’s no expectation of a big big struggle, so it’s none of those exactly. Instead it simply has No Ending. If there’s a subcategory, it’s Aborted Arc. In other words, there’s no character arc. We expect one, of course, but it has been abandoned.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE REALLY UGLY DUCKLING

WHO IS THE MAIN CHARACTER?

At first we’re introduced to the entire family. If you read the really old fairytales, like those transcribed by Charles Perrault, you’ll find that before the story even starts we get a rundown of the main character’s family history, and it’s not even brief. The Charles Perrault version of Sleeping Beauty goes into a whole heap of family stuff we don’t need to know. This re-visioning uses the tradition, sticking pretty closely to it for the first paragraph. So far, so good. We have an ugly duckling, the most interesting character in this otherwise unremarkable family of ducks.

What’s wrong with them?

He’s ugly. Based on a human world, being ugly means you’ll be shunned in this community.

WHAT DOES THE UGLY DUCKLING WANT?

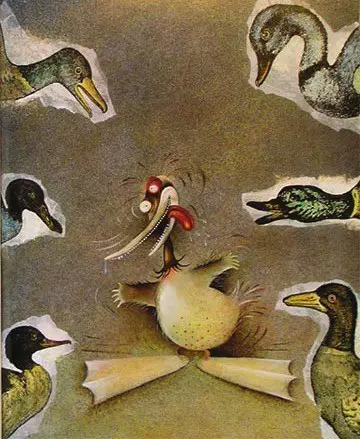

He’s looking forward to growing up. He’s obviously read the original fairytale (like us) so he is comforted by the fact that he’s only temporarily ugly. The illustration shows that he’s not worried about looking ugly. He’s smiling as everyone watches on.

But we want him to grow up to be beautiful. The Hans Christian Andersen original is basically a revenge tale. “I used to be ugly, but ha ha, look at me now!” The Ugly Duckling is the original makeover trope.

OPPONENT/MONSTER/BADDIE/ENEMY/FRENEMY

Ugliness in itself wouldn’t be a problem if peeps (and cheeps) weren’t so judgey.

WHAT’S THE PLAN?

To grow up and become beautiful. In the meantime, don’t care. This subverts the characterisation of the original duckling, who cared a lot what others thought of him.

BIG STRUGGLE

Turn the page and you get massive font, suggesting a shouty argument:

Well, as it turned out, he was just a really ugly duckling. And he grew up to be just a really ugly duck. The end.

There is no big struggle within the story itself.

WHAT DOES THE CHARACTER LEARN?

Nothing, but we readers learn we’ve been tricked. That’s the thing about postmodern picture books like this one. The reader is very much part of the story. The characters talk to us. It is likely us who changes rather than the fictional characters.

HOW WILL LIFE BE DIFFERENT FROM NOW ON

It won’t! It really won’t.

As you can see, Jon Scieszka created a gag by chopping off the last three steps of your typical story.

He subverted our expectations, using our ‘intertextual’ knowledge of the Hans Christian Andersen original.

It’s a decent gag.

The writers of SpongeBob Squarepants like it too: