A Quiet Place is a suspenseful 2018 film directed by John Krasinski, also starring John Krasinski. John Kransinski shares a writing credit with two other guys.

A Quiet Place is one of those films where if you see the trailer, you’ve seen the whole film. So don’t watch the trailer if you intend to see the film. Don’t read this blog post, either.

But here’s a teaser which does a good job of conveying the soundscape.

Stephen King thinks it’s pretty ace. He thinks the soundscape is especially ace, and so did the people dishing out Academy Awards.

I agree — I was waiting for the film-makers to scare me with a loud sound, as a cheap trick after lulling me into a false sense of security with the silence, but I am happy to report they did not do that at all.

A QUIET PLACE log line

In a post-apocalyptic world, a family is forced to live in silence while hiding from monsters with ultra-sensitive hearing.

IMDb

THE TAG LINE

If they hear you, they hunt you.

Beautiful alliteration. It’s almost like they started with the tag line and built a movie around that…

THE PREMISE

I chuckled at what Owen Glieberman had to say about the premise:

A Quiet Place is a tautly original genre-bending exercise, technically sleek and accomplished, with some vivid, scary moments, though it’s a little too in love with the stoned logic of its own premise.

WHY DON’T THEY JUST…?

This is definitely one of those films which requires its audience to sit back uncritically and enjoy the tone. As soon as credits started rolling, my husband said, “Humans are pretty damn good at making noise.” When drawn on his point, he explained how it’s hugely unlikely that a few farm-dwelling types would be left alone to deal with this issue without authorities — surely any but the most incompetent of authorities have the means to create massive amounts of industrial noise, pairing that with explosives to attract the monsters (who behave like moths to a flame) and kill them all at once. Doesn’t America spend a lot of money on its military for this exact scenario?

Don’t go there. Resist the refrigerator moments.

I personally don’t possess the ability to turn it off. My fridge logic started much earlier, when each member of the family is shown walking home along the railway line, each isolated rather than huddled in a group.

The youngest is plucked off, of course. In a setting like this, wouldn’t they huddle together? This weird spacing between family members was cinematic but unrealistic. The situation is lampshaded later when the wife regrets not carrying the son, especially since her hands were free. Regret doesn’t explain why they were walking home with that weird spacing between them. That small thing was actually my biggest issue, if we don’t count the ridiculous speed at which the basement filled with water. If you’ve ever filled a pool you’ll know it takes a lot longer than that. Or perhaps we’re meant to fudge the timing of events, in the same way we’re meant to fudge the timing of events in Thelma & Louise.

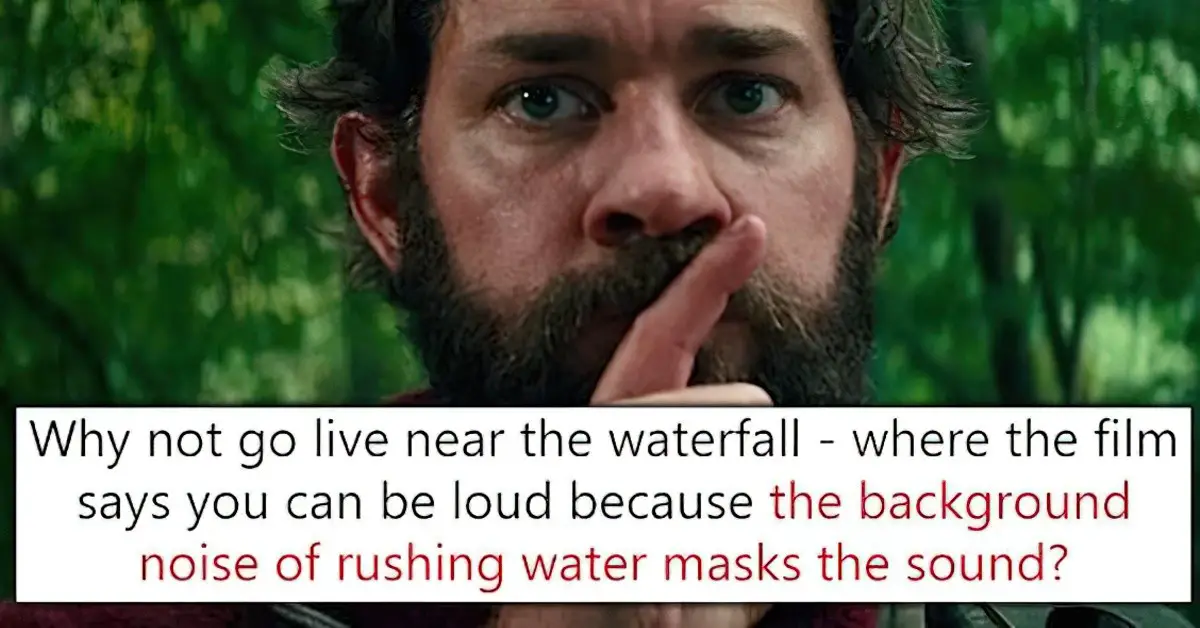

There’s also this, with meme made by College Humour:

You never want the audience to go, “Why don’t they just…”

I didn’t think they should live next to the water fall — the family needs to grow its own food. The family needs to live on a farm, now more than ever. But I did wonder why they didn’t more time there, just talking. It’s only a walk away.

“But there are supernatural monsters!” you might say (correctly), and if you can believe monsters instantly appear at the slightest noise to gobble people up, can’t you suspend your disbelief for the rest of it, too?

Unfortunately that’s not how suspension of disbelief tends to work. Quite the reverse — the more unbelievable the premise, the more believable everything else must be, to compensate. I call it the One Big Lie of Storytelling — that an audience will believe the really ridiculous fictions (lies) of storytelling, but will expect verisimilitude in every other respect, to keep that Big Lie solid. I’m sure it’s related to one of the cognitive biases, as we’re contradictory people in our mundane lives, also.

This brings me to a feminist point, because in a story with One Big Lie, storytellers rely on The Every Man to carry the narrative.

THE EVERY MAN MAIN CHARACTER

I love how the White Guy presidential campaign strategy is to play up being a “regular guy.” An Everyman.

Meanwhile, every single female candidate has to prove she’s cured cancer but also to not take any credit for it.

Marcie Bianco (@MarcieBianco) April 25, 2019

I read a lot of tweets — only a few stick in my memory. A Black woman I follow once posted a tweet which said “I’m sick of seeing faces like this whenever I watch anything on the screen” and she attached a picture of John Krasinski as he appeared in The Office. The guy who looked conspiratorially at the camera just had to be a white man, right? We all get white men.

It’s true, Krasinski has the perfect ‘Every Man’ look, along with Steve Carell, Tom Hanks and [insert white male actor who isn’t too good looking but still really good looking if he was your neighbour].

And as well as using those quote marks around ‘every man’, it’s about time I clarified what I mean by the term, because there is nothing Every Man about the White Man. Even in overwhelmingly white USA, white men comprise only 31% of the population.

In contrast to the Alpha Man (Brad Pitt, Cary Grant et al) the Every Man has a specific function in story. This is the ‘uninflected’ character, with whom anyone of any gender is expected to identify. He is a lower mimetic hero than the Alpha Man (to use the terminology of Northrop Frye). The hope is that we can put ourselves in his position very easily, men and women. In children’s literature we have the ‘Every Boy’, who functions in exactly the same way. Hence, that old chestnut: Girls will read stories about boys but boys won’t read stories about girls. (Not true but also quite true, because of social conditioning.)

This Every Man archetypes works in storytelling (and in favour of white men) because we live in a world with white and male as default. (The cognitive bias affecting storytellers here is The Default Effect.)

This is not an argument in favour of the status quo. Until we see many more stories about non white, non men, the Every Man archetype will never die. No one else will be allowed to inhabit that wonderful spot known as ‘normal’ and ‘familiar’. But the Every Man John Krasinskis are the only ones achieving significant funding to make films starring themselves, and that right there is the problem.

I love how the White Guy presidential campaign strategy is to play up being a “regular guy.” An Everyman. Meanwhile, every single female candidate has to prove she’s cured cancer but also to not take any credit for it.

@MarcieBianco

THE EVERY WOMAN

In some ways, A Quiet Place is an ensemble movie. Emily Blunt is the Every Woman. She’s white, in a heterosexual relationship, has children, wants children, cares for children, does the domestic work for her family. The Every Woman, I emphasise, is ‘Every’ only in relation to her husband, and because she doesn’t challenge the rules of patriarchy.

A note on the ending. After the Every Man husband is killed off, only then is the Every Woman wife permitted to bear arms and step in to save her family, in the masculine coded activity of bearing arms and shooting to kill. The character arc of the wife mirrors the character arc of a child in a coming-of-age story. Only by getting rid of the adults (her husband, in this case), is the vulnerable woman permitted to step up. With her husband there, and made vulnerable due to being (quite literally) barefoot and pregnant, she remains in the role of the protected. In one scene she makes her husband promise that he will protect them all.

character WEAKNESS

For storytellers, parts of A Quiet Place feel ridiculously on the nose. I acknowledge this won’t be a typical response, but every time I look closely at a story on this blog I look at the storytelling concept of character shortcoming. So when the main character in A Quiet Place to writes ‘WEAKNESS’ on a piece of paper, sticks it to the wall look at looks at this word as a reminder of mission — to find and exploit the shortcoming in the enemy — this is exasperating, head shaking stuff.

But is that just because I’ve done so much analytical thinking on this point? I’m reminded that by studying story we do ruin story for ourselves, in some ways. (And enjoy it better in other ways.)

John Krasinski has a writing credit on this film, though the spec script was written by two other guys. I suspect as Nice Guy Every Man, Krasinski had far too much trouble giving himself (okay, his character) some way in which the main character treats others badly. Characters with a moral shortcoming are far more interesting than those with only a psychological shortcoming.

The father has ostensibly treated his deaf daughter badly. She blames herself for the death of her youngest brother, and this is because of something the father has done, or not done. This is an underdeveloped part of the story. We never really get a sense of why she’d be so angry with her father. Instead, I believe the audience is left to rely on the trope of the stroppy teenaged girl, whose father can’t do anything right, even if he is trying his hardest. (Which he is — he’s trying very hard to make her a hearing aid which works.)

A moral shortcoming is at odds with the Nice Guy Everyman Trope. An actor such as Leonardo Di Caprio can pull off moral shortcomings brilliantly. Di Caprio started out as an Alpha Man, but moved quite smoothly into the role of the Every Man, as we see him in films such as Revolutionary Road. He wrinkles his face into pained, vengeful contortions and is not afraid to play characters at their worst. Di Caprio therefore belongs to a different category of white guy actors, in the same league as Bryan Cranston (who played Walter White) and James Gandolfini (who played Tony Soprano), equally unafraid to explore the moral shortcoming of the characters they inhabit.

THRILLER OR HORROR? OR MYSTERY??

Why did Owen Glieberman call this movie ‘genre bending’? What exactly is this?

Last month I looked into the writerly definition of thriller, and how a thriller differs from a horror. I clarified for myself that many stories marketed as thrillers are in fact horrors. A Quiet Place is one of those horrors which has been described as a thriller. Interestingly, IMDb lists A Quiet Place as a drama, horror, mystery.

First, is A Quiet Place structurally a thriller or is it a horror?

Like a thriller, A Quiet Place focuses on the fear, doubt and dread of the main character. However, the main character is more ‘main family’, turning it into an ensemble cast drama — we see the dynamic between members of the family.

Like a thriller, monsters, terror and peril prevail. We know this is a really dangerous world.

Many thrillers have romantic subplots.

The romantic subplot in A Quiet Place is between husband and wife, and is really only one scene, which makes this a little unusual — in a thriller the romance is most often a budding romance, in which the (heteronormative) man and woman are thrown together by circumstance and tested by external forces, impressing each other with their problem solving ability and falling in love after shared trauma.

(I did think Emily Blunt and John Krasinski made a convincing couple, completely forgetting that they are a couple in real life.)

The monsters in A Quiet Place do not run on logic. They are drawn to noise as if by instinct. They do not run on their own understandable (to us) logic. This makes them more like typical horror monsters — undefeatable. But these monsters do have a shortcoming, which makes them ultimately defeatable. This makes them more like thriller opponents than supernatural ones.

Why is this film listed on IMDb as a mystery? A Quiet Place does not outsmart the audience. In this way, it is far more thriller than mystery. I’m sure we all work out before the characters do that the monsters can be defeated by the high-pitched feedback that comes out of the daughter’s hearing aids. We sit back and hope the family works it out before they are killed off, one by one. In writing terminology, the viewer is in audience superior position.

What is the big question? The question is to do with the shortcoming, as mentioned above. If the viewers can work out the mystery of the monsters’ shortcoming, they can defeat the monsters.

A Quiet Place is most clearly a horror, specifically what has been called Isolation Horror.

A QUIET PLACE AS ALLEGORY?

A Quiet Place emphasises the vulnerability of the average person, and goes one step further by saying something — or trying to — about what it’s like to be deaf. This is a part of the theme I don’t understand. This is either because I’m not deaf, or because it really didn’t say anything profound at all. The monsters could be considered an allegory for the increased vulnerability of people who are missing one of the five senses. Even the hearing characters in this story are living like deaf people, unable to hear because they’re unable to make sound. They make use of American sign language. In this way, we are all encouraged to consider what it might feel like to be deaf.

It seems clear this film didn’t start out as an allegory about being deaf:

The kernel of the idea came to us when we were in college. We were making microbudget films and studying film history,” recalls Woods, who has been best friends with Beck since sixth grade. “We fell in love with Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and all the things that can be accomplished without sound. We wanted to do a modern-day silent film that lived in the suspense genre.

It was Krasinski who pushed for a deaf actress, which is absolutely the right decision when writing a deaf character. But that fact alone doesn’t make this a story about the deaf experience. That would have to be written by, ya know, deaf writers, not least because people who use hearing devices saw plot holes that the rest of us did not. Egregiously, the movie is captioned for a hearing audience.

Cast diversity is an important first step for Hollywood. Let’s not stop there. Others in the deaf community have been less grateful to simply see deafness on screen, and rightly so. This article starts off by describing the concept of ‘Deaf-Gain’ (a good thing) then goes on to critique the tired message that loss of speech is tragic.

In the end, to my dismay, I found “A Quiet Place” is actually yet another purveyor of the trope of disability being inextricably yoked to and dependent on technology, part of what disabilities scholars call “the medical model.” It instantiates the belief that technology providing a scientific and/or medical means of “curing” or normalizing people who are not “species-typical” is to be lauded.

“Sure,” the film seems to say, “ASL provides a good short-term ‘fix’ ― it can give you a way to communicate, and you can get by. But like the father’s ham radio signals, its reach is sadly limited; signing will only get you so far. You still remain silenced, imprisoned, forced into the margins. The only thing that will truly banish the ‘monster’ ― the only thing that will get things back to ‘normal’ ― is that screech of technological feedback.” Being deaf and signing is not enough. Regan needs her implant to restore the world to normalcy.

This is not a truly deaf-centric world. In this film, silence is scary ― at least it is for hearing people. The deaf people I talked to don’t seem to find this film all that frightening, because for them it’s not an unknown, it’s not a loss, it’s business as usual.

Others have said A Quiet Place is a metaphor for the terror of parenthood, similar to Emma Donoghue’s Room. Possibly because this is Krasinski’s line, too.

THEME

Possible, undercooked allegory aside, the message of A Quiet Place is extremely conservative and non-controversial — in line with the suspense genres in general.

If we can’t protect our children, who are we? Emily Blunt’s character asks John Krasinski’s character after beseeching him to protect them all.

I challenge a single member of the audience to disagree with the idea that protecting children is a bad thing.

There’s more to that, though. The idea that ‘family is everything’ is possibly becoming a little controversial as more and more human pressure is heaped upon our fragile planet. I wouldn’t be surprised if the ideology of A Quiet Place seems outdated in 20 years’ time, as a new generation of viewers grow up under the threat of climate change. Many may choose not to procreate, in deliberate favour of returning the planet to its former equilibrium, last seen before humans left Africa.

BIRTH ON FILM

I’m sure anyone who’s had a baby gasped at the family’s decision to have another baby. Because babies cry. BABIES CRY A LOT.

The characters do have a plan — they keep the baby in a box (like a little Moses — the basement filling with water is basically a Moses scene). They also have some kind of ventilator on his face and I suppose they were drugging him to keep him quiet. If there’s anything morally controversial about this film it’s, should humans procreate in times of great stress? Is it ethical to bring new life into a dangerous world? Looking at human across cultures and across history, it seems to me that humans are especially keen to procreate in trying circumstances — the more trying the circumstances, the more we feel the procreation instinct.

But first comes the birth itself, of course. I know it’s possible to give birth silently because a friend’s mother has always boasted that she didn’t make a sound. This sounds like a special kind of torture to me, but ladies be ladylike.

People who have given birth know that, the vast majority of the time, water doesn’t break like that, as an early sign of labour. Quite often the water has to be broken for you, in fact. This is an old Hollywood trick and hopefully most viewers know by now that just because it happens like that sometimes, it happens quite seldom.

There’s one birthing trope that irritates me far more, because I feel it is understood far less, and probably has an impact on real birthing pain.

I’m talking about the shots of labouring women flat on their backs. Unless hooked up to machines, in which case other poses are impossible, women in labour naturally tend to choose a very primal, unattractive, animalistic pose — on all fours, weight forward at least. Unless medicated, lying flat on your back while giving birth is next level torture. Emily Blunt in the bath, basically on her back, already in pain from her foot, also in pain from contractions, is a heavily unrealistic scene for me. But Emily Blunt has herself given birth and presumably had some say in the direction. I can only conclude that Hollywood storytellers don’t care about this sort of realism, preferring the ‘pretty pain’ shots. I only hope that people in actual labour throw out Hollywood ideas of what birthing looks like going in.

Mind you, I don’t think audiences really want to know what real labour looks like. I’ve never seen a Hollywood actress poo during labour. Midwives actually tell you to shit the bed — if you’re shitting the bed, you’re pushing correctly. And the amount of blood and blood-like fluid that comes out of a person during labour is more intensely horrifying than any horror film will ever manage.

Do women ourselves want the world to see us at our most base? I actually doubt it. So we all go on pretending that birth looks more like Emily Blunt in the bath. The particular labour of womb-owners remains largely invisible.

SYMBOLIC STORYWORLD

This is a setting reminiscent of fairytales, with humans living next to the ominous forest. Dark beasts come out of the forest. When humans enter the forest, they are facing their darkest fears. Forest equals the subconscious.

With the corn silo, the film-makers are also making much use of The Symbolism of Altitude. Characters in films go to high places in order to gain insight.

The house itself is a Symbolic House. It falls into the ‘warm house’ category, with its candles and a whole lot of clutter I’d be getting rid of, since if something falls over they’re all dead.

A Quiet Place feels like a very specific wish fulfilment fantasy — the wish to be self-reliant. I am vulnerable to this particular fantasy myself, ever since I read Little House In The Big Woods at the age of six. I loved that the Ingalls family had no dolls and made them out of rags. Even now, I occasionally watch Doomsday Preppers, part baffled by the display of conspiracy thinking, but also partly because I’m one step away from digging my own crazy hole and stockpiling cans of tuna.

The farm of this family is straight out of a picture book utopia, let’s face it. See also: Storybook Farms. There’s that big, red all-American barn, the fairy lights (which aren’t fairy lights, but look like that from a distance, in line with Stars Hollow of Gilmore girls.) Living self-sustainably is not pretty. Even on a highly successful self-sustaining farm, there are times of the year with slim pickings. I know this from my career in watching self-sustaining documentaries. But this family is depicted in a time of plenty, lifting smoked fish from under the floorboards like they’re dining at a fancy restaurant.

There’s an idea trending in America that moving from the city back to ‘your roots’ (the country) is a virtuous thing to do, and that this is how to fix the huge city-rural political divide. Lyz Lenz wrote a rebuttal of that ideology at Vox: Move back to your dying hometown. Unless you can’t. I mention this here because films such as A Quiet Place depict rural life as a utopia, or rather an snail under the leaf setting, and it definitely ends with the characters about to return to a utopian rural life. America does tend to glamorise this life.

I cop to sharing the self-sustaining fantasy as depicted in this film, but I’m not such a fan of the return to a patriarchal order which dystopian stories so often revert to, without question. We see mother and daughter back in the kitchen. We see father training son to look after his mother. Men as protectors, women inside the house.

This is the fantasy of dominant, patriarchal culture.

And I don’t want audiences to just swallow that one whole, either, just because the outtake image is Emily Blunt holding a big gun. That’s where we’re at with feminism in Hollywood. This is fake feminism. This is a version of gender equality when the creators lack imagination, when they can’t fathom what society would look like without a patriarchy. The best they can do is women as patriarchal men.

I want to see stories — dystopian or not — in which people of all genders use their various skills to work together, without expecting masculine types to hold the guns until they’re killed off and cannot hold them anymore.

I don’t want storytellers to allow female characters their arcs only after killing off the men. It’s kind of sick and I’m kind of sick of it. How do we move forward as a society when we hold this ideology as the unquestioned ideal? If this is the fictional story we’re happy to swallow, will we question sending our sons to the slaughter next time war breaks out?