Pygmalion was a sculptor who falls in love with an ivory statue he had carved. The most famous story about him is the narrative poem Metamorphoses by Ovid. (Pygmalion can be found in book ten.) In this poem Aphrodite turns the statue into a real woman for him. In some versions they have a son, and also a daughter together. According to Ovid, after seeing the Propoetides he was “not interested in women”. His statue was so beautiful and realistic that he fell in love with it.

In time, Aphrodite’s festival day came, and Pygmalion made offerings at the altar of Aphrodite. There, too scared to admit his desire, he quietly wished for a bride who would be “the living likeness of my ivory girl”. When he returned home, he kissed his ivory statue, and found that its lips felt warm. He kissed it again, and found that the ivory had lost its hardness. Aphrodite had granted Pygmalion’s wish.

Pygmalion married the ivory sculpture changed to a woman under Aphrodite’s blessing. In Ovid’s narrative, they had a daughter, Paphos. The city’s name comes from this.

In some versions Paphos was a son, and they also had a daughter, Metharme.

Basically, Pygmalion/Daedalus is a story in which a man gives birth to a woman. You might say, it’s a type of wish fulfilment for men: The wish to create someone, especially someone in his own image. The creator might be deformed, and wishes he could have the advantage of beauty, like a beautiful woman. (Because women are the main objects of The Gaze.) Or maybe he’ll change a small thing about her to make her his version of ideal. Or it might be about controlling her fertility.

The Pygmalion/Daedalus story has been told many times, and continues to be told. There is inherent misogyny in this story, of course, or at least there is in many modern renditions, unless the whole point of the retelling is to point out the misogyny. The modern narrative is that a man makes a woman into who she is. Ironically, the men do not find fulfilment for having helped a woman fulfil her potential. His control of her generally leads to his downfall rather than to exultation.

As feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey once put it, the woman stands as a “signifier for the male other, bound by a symbolic order in which man can live out his fantasies and obsessions through linguistic command, by imposing on the silent image of woman still tied to her place as a bearer of meaning, not maker of meaning.”

PYGAMLION AND LITERATURE FOR ADULTS

Some examples in stories for adults:

- The Winter’s Tale, William Shakespeare, about controlling pregnant women’s bodies among other things

- Million Dollar Baby, the 2004 film starring Clint Eastwood, who turns trailer park kid Hilary Swank into a prize fighter. The film poster would have you believe that this is a film about a female protagonist, but the real hero — the one who changes over the course of the story — is Clint Eastwood.

- Annie Hall, the 1977 Woody Allen movie. Annie actually resists Alvy’s attempts to turn her into something in his own image, subverting the story. (Woody Allen is a feminist? Who knew!)

- The Phantom of the Opera, who falls in love with an obscure chorus singer Christine, and privately tutors her while terrorizing the rest of the opera house and demanding Christine be given lead roles

- Titanic, becauseJack helps Rose speak out and assert her independence from her suffocating family and fiance.

- The Birth-Mark by Nathaniel Hawthorne, in which a man is repulsed by the birth-mark on his wife’s cheek, so dreams he cuts it out with a knife while she’s asleep, comparing himself to Pygmalion. The man is a natural scientist, so in real life makes a concoction and has her drink it.

- George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion. A professor of phonetics wagers that he will be able to transform the cockney speaking Covent Garden flower girl, Eliza Doolittle, into a woman as poised and well-spoken as a duchess.

- Pretty Woman, in which creator and created are united at the end (and is probably why audiences loved it so much)

- John Cheever’s short story “Metamorphoses” translates legends from Ovid into Westchester settings.

- Lars and the Real Girl is a film starring Ryan Gosling about an off-the-page autistic man who orders a sex doll and forms a relationship with her. By the end of the movie he has buried the doll and looks set to form a romantic attachment with a real woman. The doll has been a necessary middle step. This ending is considered a triumph according to neurotypical standards, because Lars now conforms more comfortably to societal expectations.

Stories in which a man helps a woman have a sexual awakening might also be considered part of the Pygmalion wish-fulfilment fantasy of men. This can be traced at least as far back as fairytales:

The disadvantage — or, if you prefer it, the advantage — of being a princess is that you are essentially passive. You just sit there on your throne, or on a nearby rock, while the suitors and the dragons fight it out. In an extreme form of this passivity you are literally asleep or in a trance like Sleeping Beauty or Snow White. This particular archetype is one that has always appealed to men, and it turns up again and again in their fiction. The trance takes different forms: sometimes it is physical virginity, sometimes it is a sort of psychic virginity. Often the princess is frigid, or sexually unawakened like Lady Chatterley; sometimes she is intellectually or politically awakened, like Gwendolen Harleth in Daniel Deronda or like the Princess Casamassima in Henry James’s novel of the same name, which is in many ways, and not always successfully, very much like a fairy tale.

Alison Lurie, Don’t Tell The Grown-ups: The subversive power of children’s literature

This Pygmalion trope is not limited in stories for and about men, written by men; take the Fifty Shades of Grey series by E.L. James. The success of this series shows that the trope has worked its way into a widespread female fantasy of the 2010s.

PYGMALION IN PSYCHOLOGY

The Pygmalion effect, or Rosenthal effect, is the phenomenon whereby higher expectations lead to an increase in performance. A corollary of the Pygmalion effect is the golem effect, in which low expectations lead to a decrease in performance; both effects are forms of self-fulfilling prophecy.

PYGMALION AND CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

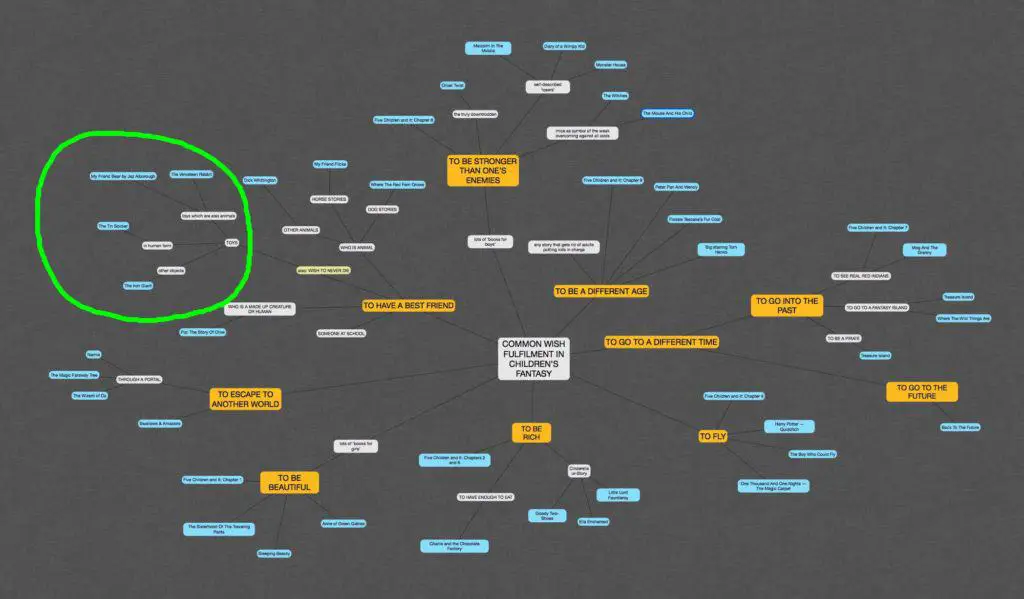

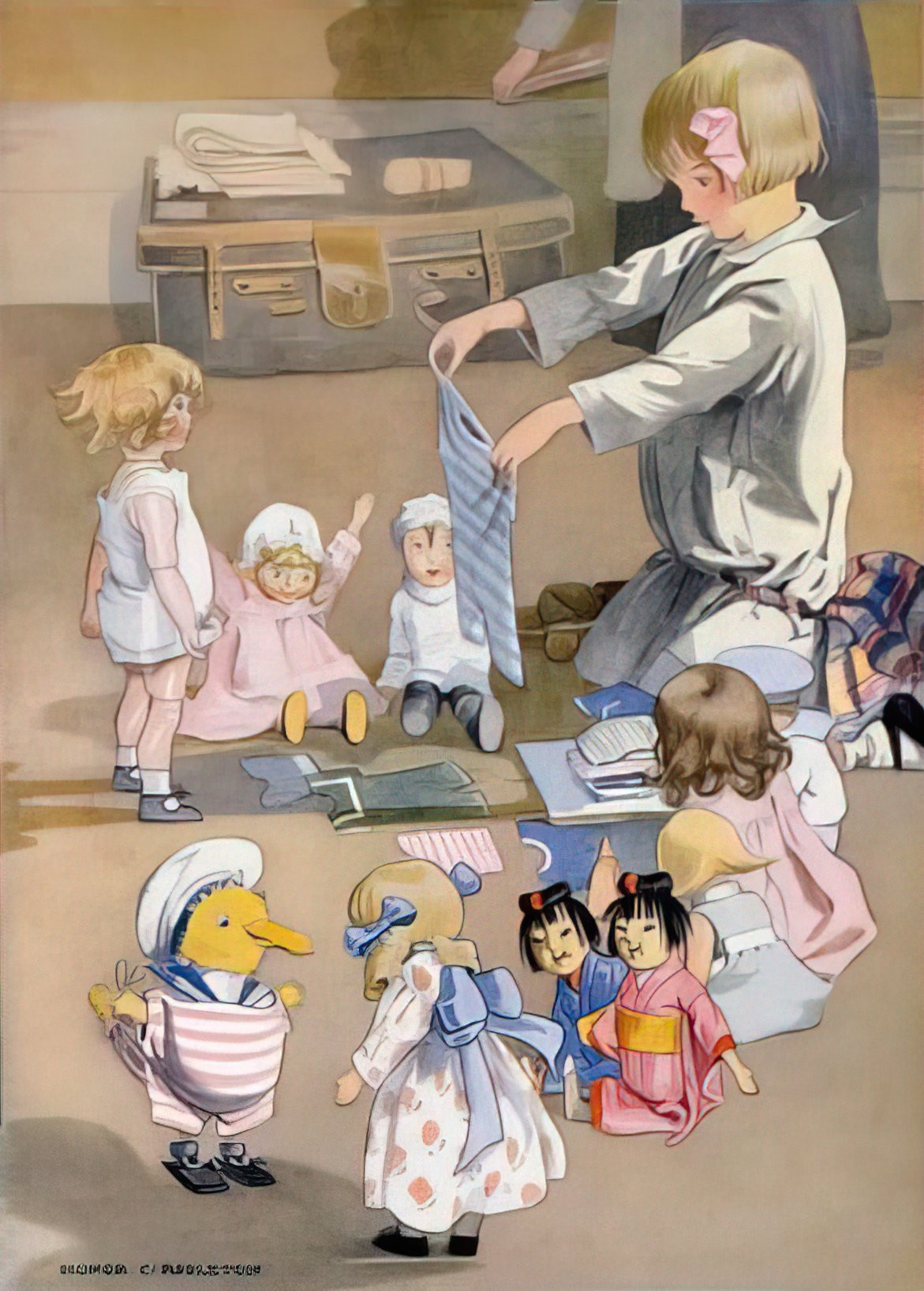

What about Pygmalion stories as they apply to children’s literature? Well, there are many, many children’s stories about talking toys. Toys have a place in certain types of wish fulfilment stories: The wish to have a friend and also the wish to never die, especially when toys are mended, or when they can be re-wound, in the case of a wind-up toy. (The modern version would be having its batteries replaced, if this kind of story were more common today.)

The wish for one’s toys to come to life as friends is a common wish-fulfilment fantasy in children’s literature, and I propose that this is the childhood analogue of the adult Pygmalion fantasy.

Maria Nikolajeva makes no distinction between the role of talking animals and the role of talking toys in children’s literature. Whatever can be said of animals can also be said of toys. Though the function is the same, Margaret Blount does make a distinction between who tends to tell which kind of story to whom:

Human is what the child wants his toy or pet to be, the substitute friend or brother, like himself but exempt from all the dreary rules attached to childhood and growing up, the eternal confidant or companion, steadfast and unchangeable. Stories about pets that speak are as old as Dick Whittington or the talking horse Falada, but those about toys that ‘come to life’ are most often of the kind that fathers and mothers tell to children in order, as C.S. Lewis mentions in Three Ways of Writing For Children, to give one particular child what it wants. They do not date back much before the Victorian Age and the time when childhood began to be considered in isolation and regarded in sentimental or romantic fashion.

Animal Land, Margaret Blount

TALKING TOYS IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

- Miniature people (who often have the bodies of mice), supernatural creatures and animated objects have similar roles throughout literature.

- Imaginary friends can go into the same category.

- Stories with talking toys therefore are quite often ‘sentimental’ and ‘romantic’.

- Talking animals are never killed — it would be too much like murder. Especially when toys are in the shape of animals, the author might as well be writing about an animal. That’s how much readers can empathise.

- There is usually no eating and drinking when it comes to talking toys and pets — it’s a bit uncomfortable that humans eat creatures without conscience.

- Characters who are toys often have delightful predictability, and sometimes mechanical behaviour which can be used to humorous effect (especially if they wind up at the back).

- Some toys talk only under certain conditions.

- Sometimes only their owner can hear them.

- Toys are made to be loved, yet what they seem to do is endure hardship with patience and steadfastness e.g. The Little Wooden Horse, who is sneered at for being simply and plainly made. (The Ugly Duckling story but in toy form.) Toys make good aesthetes since they don’t even need to eat. (See above)

- Mark Haddon has said that ‘Ultimately, there is no narrative without death‘. It seems as difficult to write about toys without saying what happened to them as it is to write about humans without mentioning death. (The town dump in The Mouse and His Child, ‘a big grim box’ for Leotard and the Ark etc.

TALKING TOYS IN THE 1800S

THE LITTLE TIN SOLDIER (1846)

It is not until 1846 that you get a story like The Little (Brave) Tin Soldier; and in nurseries, the gradual additions of strange creatures to the more conventional ‘human’ families — toy animals, the Golliwog and that indispensable piece of nursery furniture, the enduring Teddy Bear. Adults made the toys talk, and they became a child’s companions on magic adventures.

PINNOCHIO (1883)

Though the product is a boy, this is still a Pygmalion story.

MORALITY IN TALKING TOY STORIES OF THE 1800S: TAKE CARE OF YOUR THINGS!

The ideology of toy stories is often that one must take care of one’s things, as if they were almost sentient. I wonder if the throwaway culture of today has contributed to the demise of this kind of morality — it’s no longer necessary to treat your teddy bear with such great respect as an object — when my daughter’s bear went missing it was very sad but I was able to buy an identical one for two dollars at the second hand shop. In fact, the idea that a child should be so attached to their things is almost the antithetical morality of today’s stories. (Including in my own, The Artifacts.)

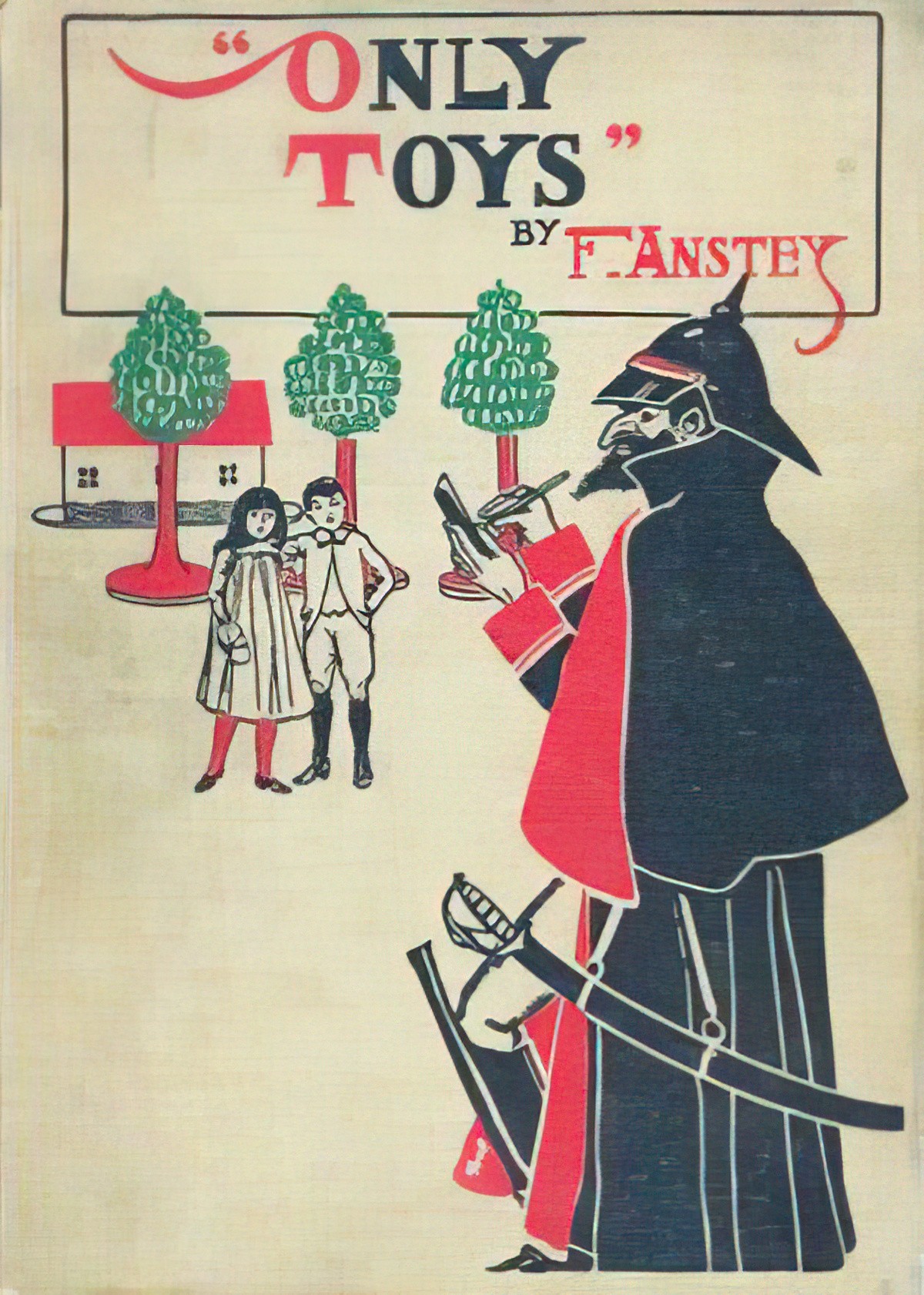

The children in Sarah Trimmer’s (History Of) The Robins (1786) were taught to feed the birds and be kind to them, as Tom had to be kind to the caddis worms. Talking toys too can give a story a certain moral ring; one must be kind to objects or possessions and the screw is turned when they prove to be human after all. Bad brother breaks his sister’s doll with the excuse that Toys Can’t Feel. Night comes and the toys come to life and of course they can feel and sometimes take a nasty revenge in a place where they are powerful and children are not (Rupert has this experience several times and once with Freudian additions in Mary Tourtel’s Rupert and The Wooden Soldier, 1928. The style is long lasting.) In fact, Toyland becomes a recognisable place for fantasy happenings and sometimes retribution from F. Anstey to Enid Blyton.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

TALKING TOYS IN THE 1900S

ONLY TOYS BY F. ANSTEY (1903)

[This story] has a toys’ vengeance theme and more interesting experiences of doll’s house living, which turns out to be as awkward as Hunca Munca and Tom Thumb found it. Torquil and Irene, transported to the place where toys are real, find their own doll’s house a very inconvenient place to be — the food is inedible, the drink not what it seems, the fire won’t burn and the kettle won’t boil. The dolls have a stiff hierarchy as wooden and artificial as themselves. But few toys stories exist without human interaction. Toys have owners as pets do and in Toyland toy and owner meet on equal terms. All animals speak, whether ‘real’, carved or stuffed; it is a place that everyone recognises, with wooden trees and animals out of the Ark, always dreamlike, an after dark playground where nothing goes really wrong — one always wakes in time.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

RACKETTY-PACKETTY HOUSE BY FRANCES HODGSON-BURNETT (1906)

You may remember in The Little Princess that Sara Crewe has a doll house and she imagines the dolls talk while she’s not there. This lesser-known book for younger children stars those talking dolls, and is told by a fairy narrator. The introduction reads:

Now this is the story about the doll family I liked and the doll family I didn’t. When you read it you are to remember something I am going to tell you: If you think dolls never do anything you don’t see them do, you are very much mistaken. When people are not looking at them they can do anything they choose. They can dance and sing and play on the piano and have all sorts of fun. But they can only move about and talk when people turn their backs and are not looking. If anyone looks, they just stop. Fairies know this and of course Fairies visit in all the dolls’ houses where the dolls are agreeable. They will not associate, though, with dolls who are not nice. They never call or leave their cards at a dolls’ house where the dolls are proud or bad-tempered. They are very particular. If you are conceited or ill-tempered yourself, you will never know a fairy as long as you live.

Queen Crosspatch

I do wonder how many young readers wondered why they weren’t visited by these fairies even though they were on their best behaviour.

THE MAGIC CITY BY E. NESBIT (1910)

Quite the most interesting and unusual Toyland was written about by, as might be expected, E. Nesbit in The Magic City — the only book, as distinct from her short stories, where she deals with talking toys. Nesbit children usually do not need toys — they are too busy having imaginative adventures by other means. Like F. Antsey’s Torquil, they might remark that toys are ‘a babyish pursuit…except when they are exact models of things’. The Magic City, or rather series of cities, is a place that can be entered only by those who have helped to build it with books for bricks; and it is populated by creatures and people that have been put there, or have managed to escape, out of the books from which it is made. H.R. Millar’s drawings give the city that slabby, Babylonian/Aztec look of any structure made of books, ornaments, chessmen and dominoes. The story has that odd, logical but numinous quality shared by The Enchanted Castle, when the children who enter the city find that it is greater inside than out and has a history, prophecies and laws that seem to be older than its creators. That the dragon outside is a toy with a winding key does not make it any less fearsome; but it is still dreamlike — and one never dies in a dream. The lions in the desert that the children encounter are Noah’s Ark lions, but fierce and predatory. These lions are killed, and when dead are found to have turned to wood once more — a dreamlike easing of otherwise intolerable consequences.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

JOSEPHINE AND HER DOLLS (1916)

HITTY, HER FIRST HUNDRED YEARS (1929)

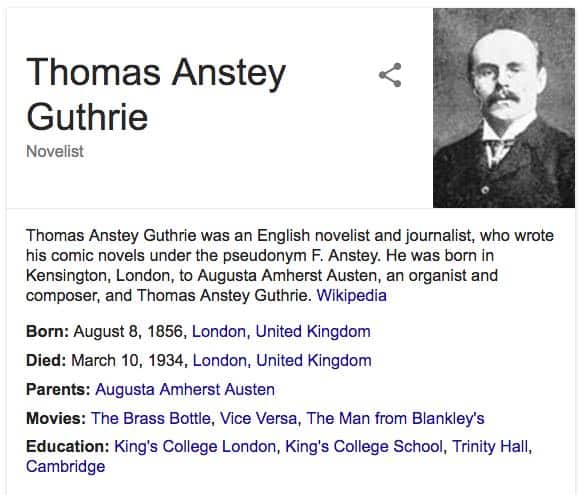

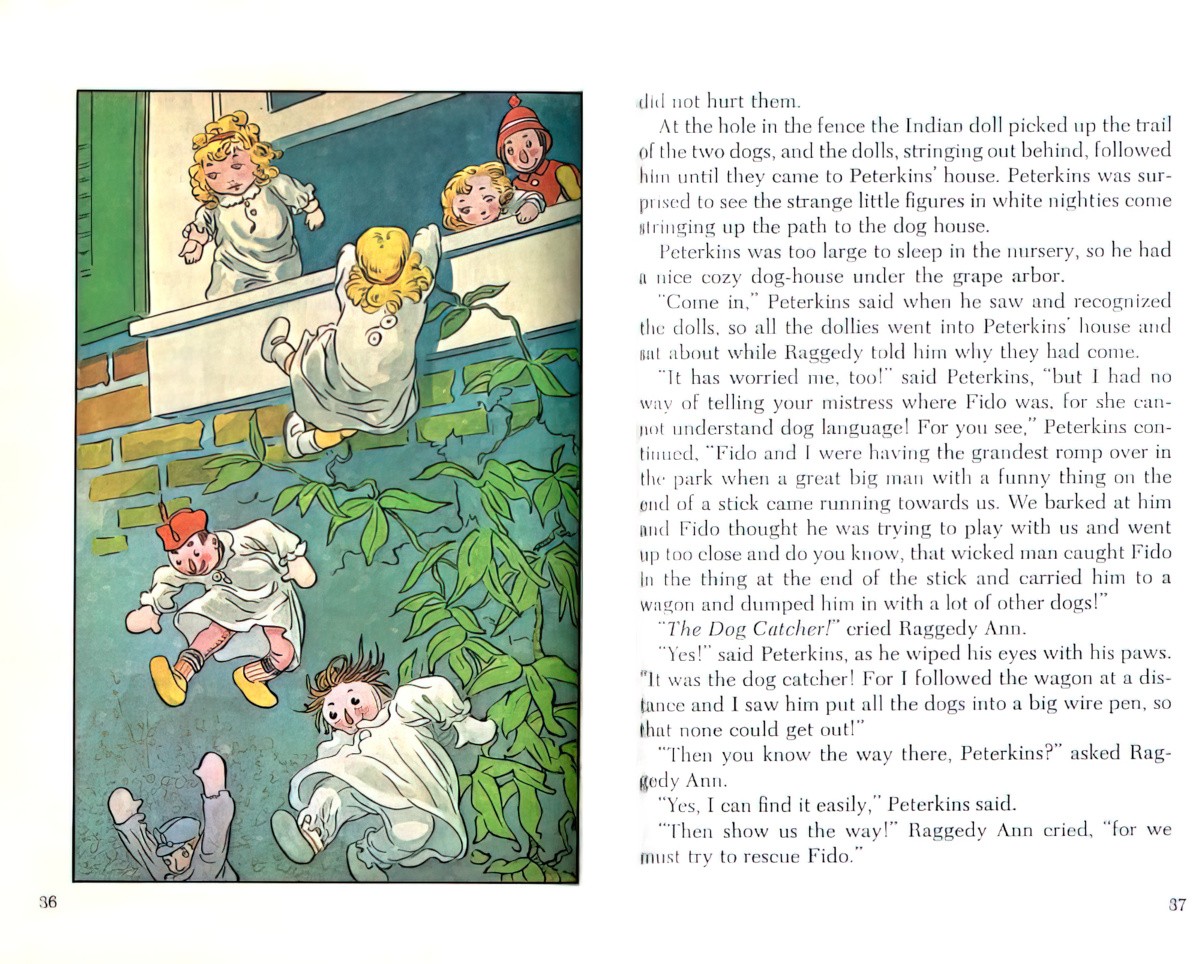

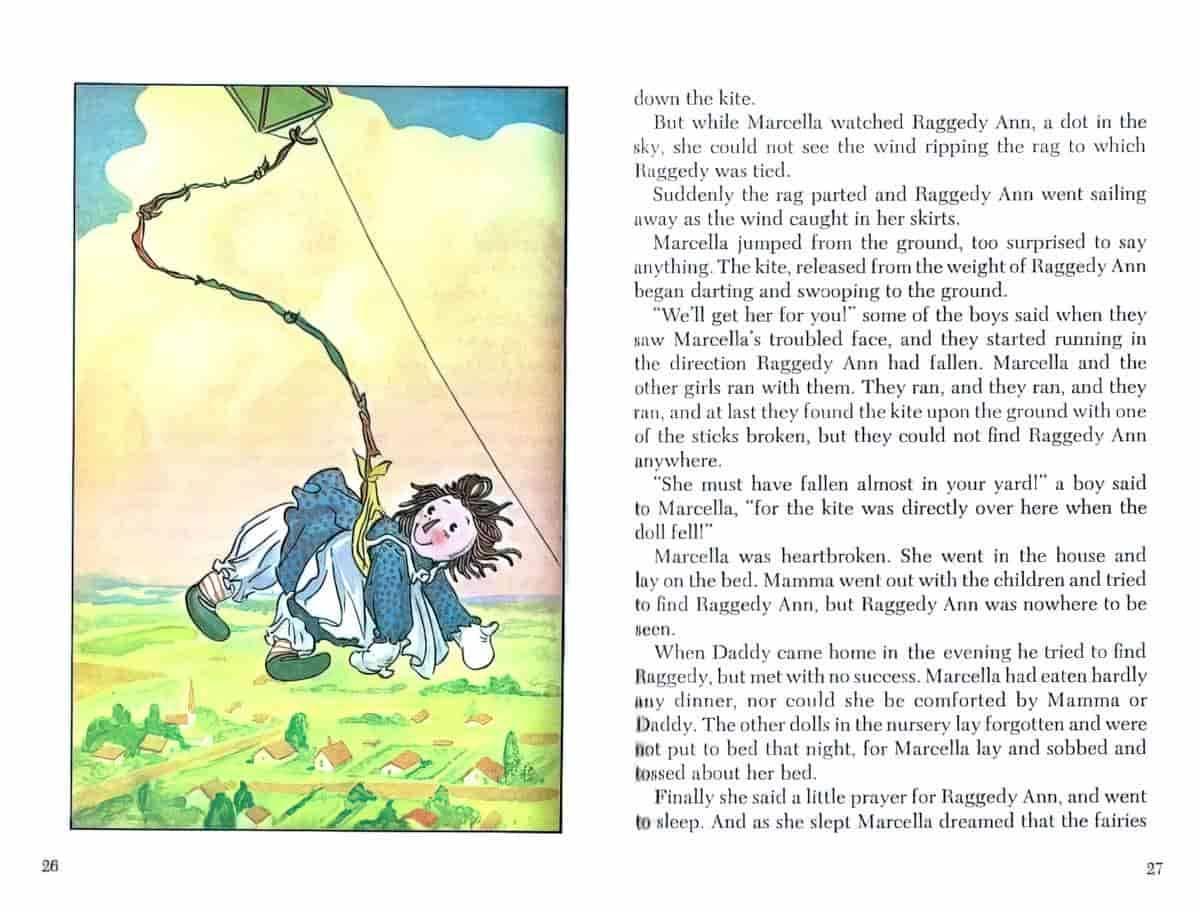

RAGGEDY ANN BY JOHNNY GRUELLE (1960s)

TOY STORY, PIXAR

All of these stories lead up to Pixar’s Toy Story, released 1995 to huge critical acclaim and huge box office earnings.

TALKING BEARS

Christopher Robin enters a world (The Hundred Acre Wood) where his toys can talk and he never has to go back, unlike Paddington/Mary Plain/the Pushmipullyu. Winnie the Pooh was modelled on the toy bear of illustrator Shepherd’s son Graham. The actual bear is quite a bit thinner, though.

A bear character is never inconsiderable; no Teddy bear takes second place in the toy hierarchy. He is always King, the first in a child’s affection. As Pooh progresses his rotundity increases, his legs and arms shorten, his back becomes humped (a rare characteristic only seen in vintage bears and never on modern ones), his head pokes forward as if in deep thought. He is the first famous fictional bear and all the others owe him something; his size, his fondness for honey, ponderous naïveté and occasional flashes of brilliance have left their mark on other lesser bears, real or toy; and there is no question about Pooh’s reality. His adventures in the Forest and Hundred Acre Wood spring as naturally from character as the happenings in any real life.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

Toys in popular children’s books are great for people in the modern era to make money — not by selling the stories themselves but by making cheap stuffed toys in China and selling those. Winnie-the-Pooh continues to be the most popular teddy bear from literature, helped along by Disney, who actually made a pretty terrible movie out of the character with none of A.A. Milne’s original wit.

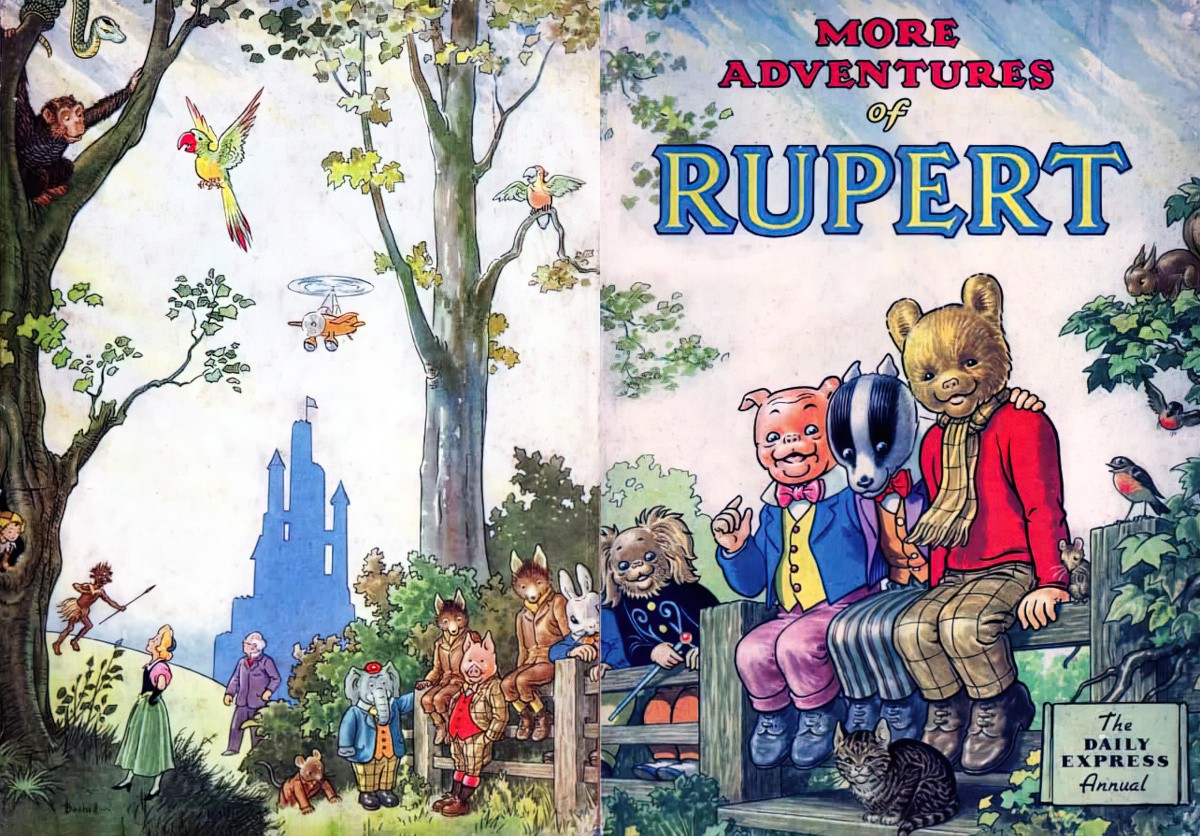

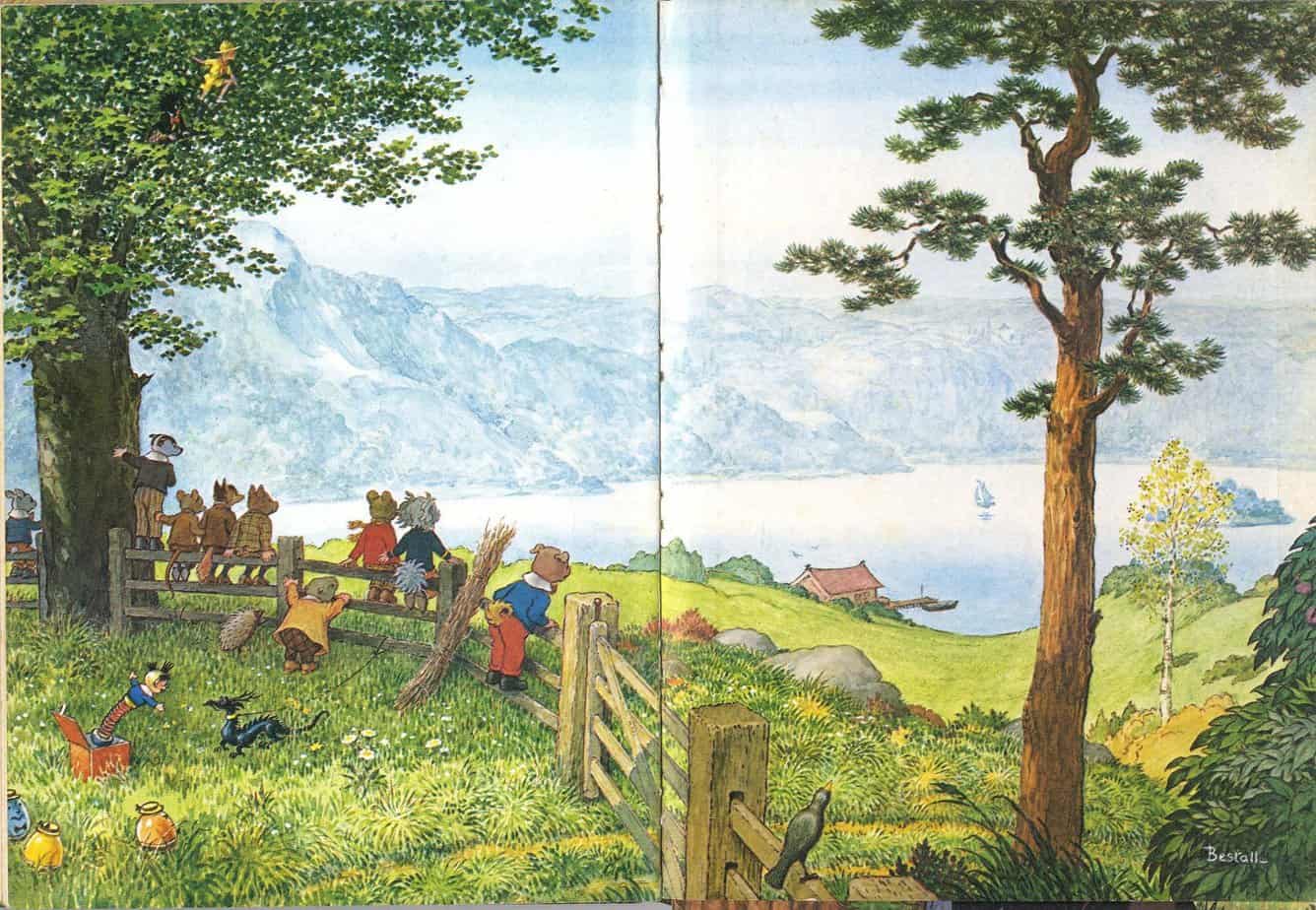

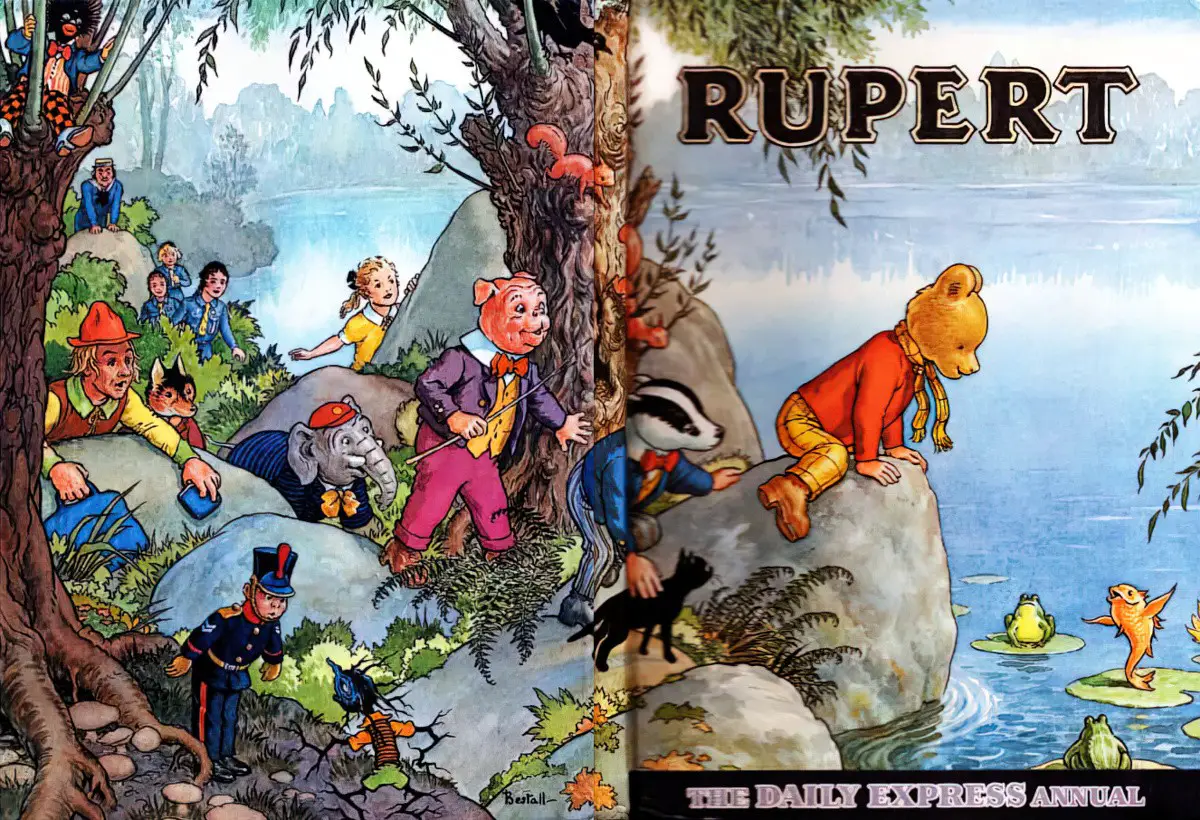

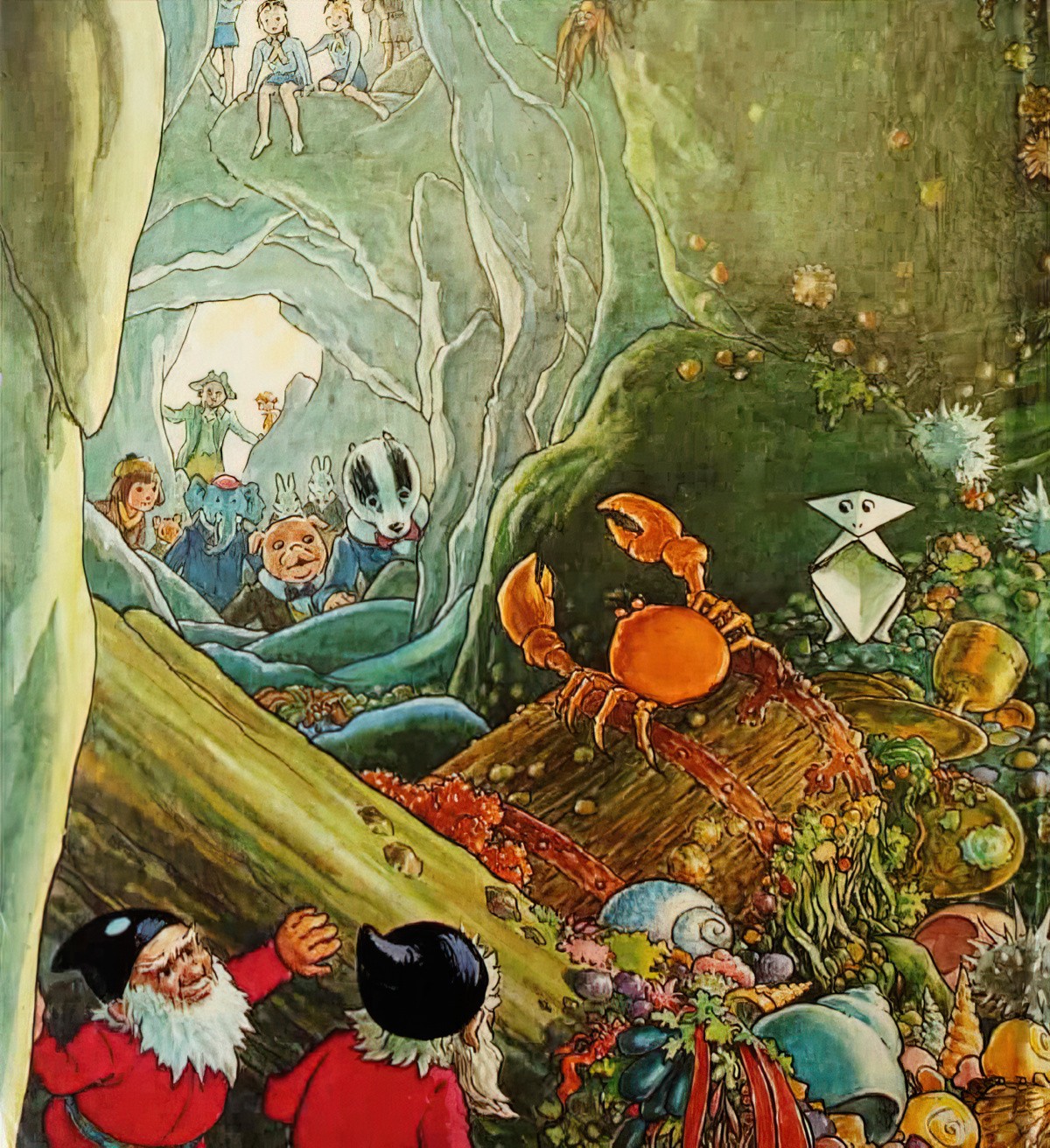

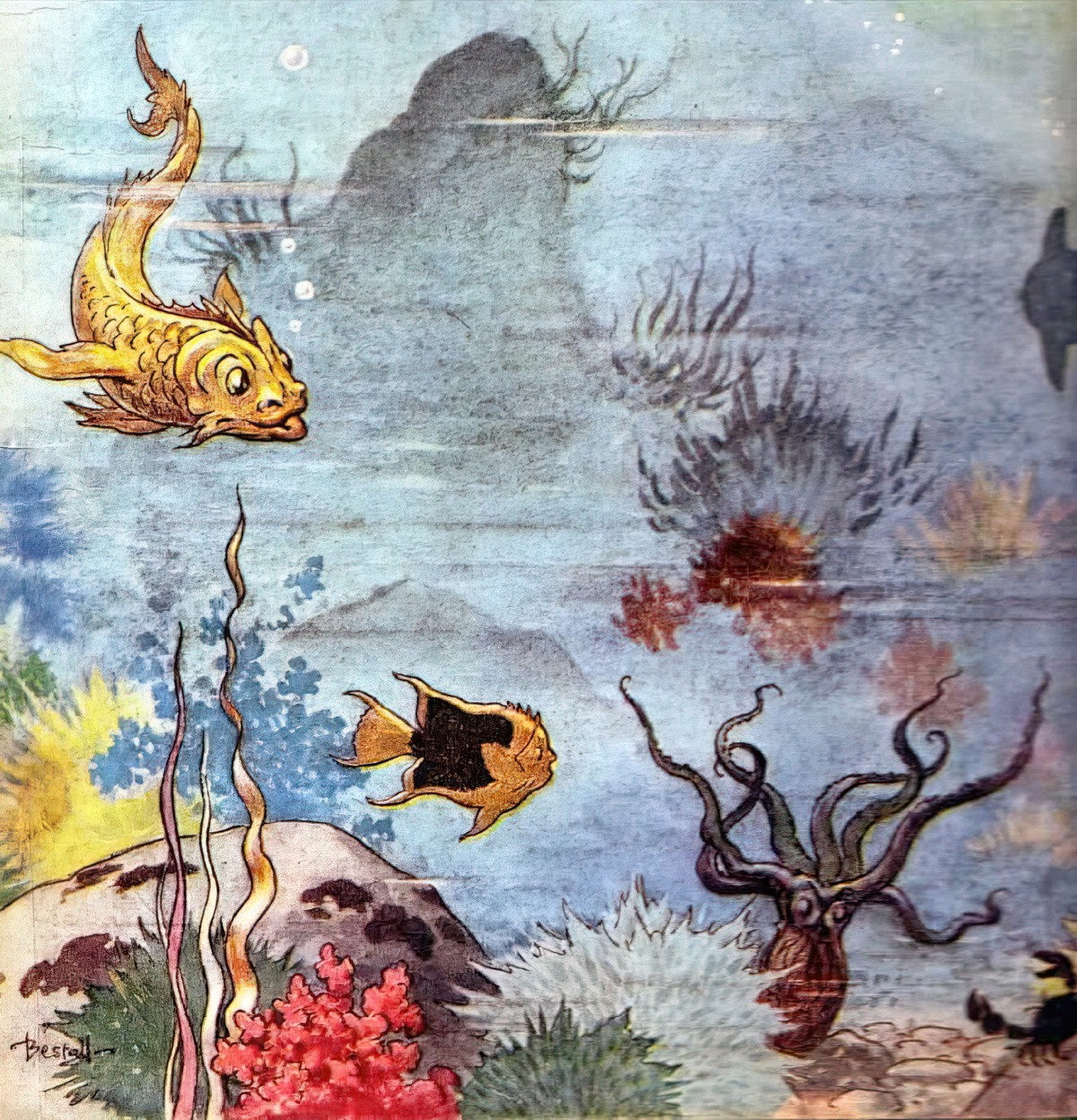

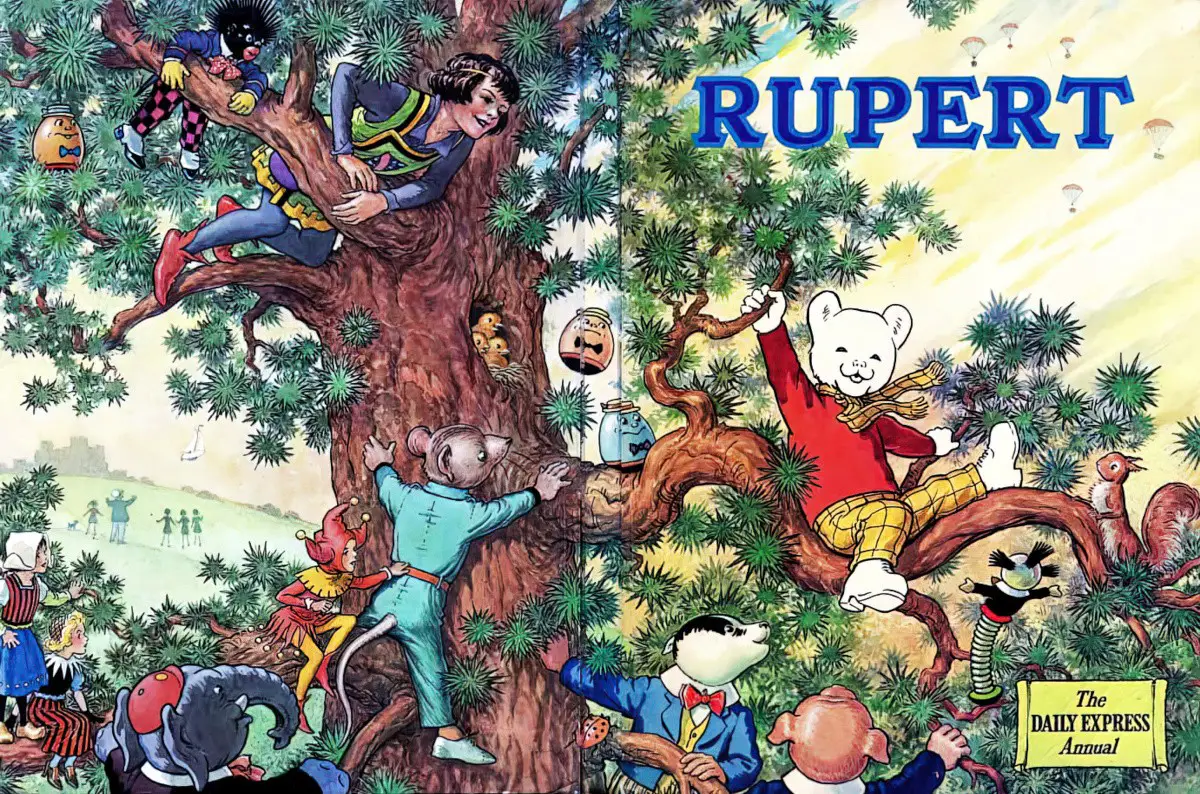

Rupert Bear (1920s and 1930s)

Take a fairy tale from Grimm, one of the more exciting but less grotesque — say, ‘The Golden Goose’ or ‘The Frog Bride‘ or ‘Rumpelstiltskin‘. Add to this some of the glamour of The Arabian Nights, some of the magic and mysterious qualities of the King Arthur cycle and some of its knightly heroism. Add a homely taste of folk tale. Blend these ingredients very smoothly. Dilute the effect by a contemporary setting or framework. Express the result in drawings of beautiful, accurate detail, with no cartoon facetiousness, and then ration the dose to a picture a day, ensuring that addicts will always demand more — and you have the Rupert Bear adventures of the twenties and thirties, and some of the reasons why he enjoyed, and still enjoys, such success and popularity.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

- The Rupert Bear entry at Wikipedia tells you the full history.

- There is no real reason for this boy to be a boy rather than a human, which makes him an ancestor of modern characters such as Olivia the pig.

- But when he was created it was pretty normal for a child hero to be an animal (a la Pip, Squeak and Wilfrid, the Bruin Boys, Bobby Bear, Teddy Tail).

- The character was created by talented illustrator Mary Tourtel.

- Tourtel tended to give Rupert stories too much plot rather than too little. The stories became simplified over the years.

- The first story was called Little Lost Bear, and was probably inspired by Goldilocks and Red Riding Hood combined. It’s a home-away-home story in which Rupert goes out into the forest, meets a variety of characters then returns home to his mother. (Woods are for getting lost in, in children’s literature.)

- Tourtel was also inspired by The Arabian Nights tales, and Perrault and Dickens.

- Tourtel’s collaborator was her husband, who was an editor. After he died — in 1931 — her stories went downhill, possibly because he acted as a restraining force. (Tourtel was first and foremost an artist, storyteller second. The pictures stopped being self-explanatory, requiring lengthy explanations to help the plot along. Also her drawing skills went downhill, due to failing eyesight.)

- The subsequent Rupert Bear stories are also of this type. “Rupert’s fate was so monotonously terrible that one wondered why he went out at all, and conversely, why his parents never bothered to worry.” — Margaret Blount

- Rupert Bear stories continued to be written by different authors, as were Sexton Blake, Nancy Drew, Sweet Valley High and The Hardy Boys.

- Rupert grew younger and was brought more up to date over the decades. He also passed from animal-boy to boy-in-a-bear’s-body. But he still retains a sort of magical power that can only come from being part human part animal.

- The setting is a place called Nutwood with no towns or cities. It’s populated by other animals and people in about equal numbers. It’s a bit like Narnia in that regard.

- Animal characters tend to be good; people (witches, magicians etc.) tend to be bad. (Apart from wolves and the occasional dragon, of course, who are also bad.)

Pooh has several direct descendants, but the closest is probably Albert, created by Alison Jezard from 1968 onwards.

Illustrator Margaret Gordon even makes him look like Winnie.

TEDDY ROBINSON (1955 onwards)

Teddy Robinson’s life is limited to that of his owner Deborah, and he lives in the real world of ‘I said to Teddy and he said to me’, or of Christopher Robin’s Binker, ‘I have to do it for him.’ He moves when Deborah moves and stays where Deborah puts him. His adventures are those of a toy who has thoughts and makes remarks, but is quite unable to move or initiate action. To Deborah he is a child, bear and friend. […] In Deborah’s absence, Teddy Robinson can talk to blackbird, snail, tortoise and kitten; and to Deborah he makes short, simple, acquiescent remarks. Each loves the other wholeheartedly and their lives are totally shared — in many ways Teddy Robinson is the most ‘natural’ bear of all. His personality reflects Deborah’s in the ageless way of well-loved toys, and his adventures are those of getting lose, left behind (on a sandcastle) and forgotten (in a tool shed), placed for sale in a shop window, thrown into a tree by ‘a boy who ran round the garden shooting at people who weren’t there until they were all dead, bouncing on a piano while it is being thumpingly played at a party, playing the games that one insists on one’s toys playing too, being turned into pirate or Indian, or sent to the toys’ hospital.

Margaret Blount

Some of these adventures may remind you of more contemporary books. For example, Shirley Hughes uses the ‘gets lost and winds up for sale’ in her story Dogger.

TALKING TOYS IN THE 21st CENTURY

TALKING TOY OR IMAGINARY FRIEND?

There are still plenty of talking animals in picture books — take Ian Falconer’s Olivia series, for instance. But modern stories don’t tend to be talking pets and toys — they are just animals that talk, no more questions asked. There are plenty of good reasons for depicting people as animals in picture books, especially.

Also common in modern children’s literature are imaginary friends, or if not friends, creatures who stick around for a short time then depart.

- The Lost Thing by Shaun Tan (2000)

- The Adventures of Beekle: The Unimaginary Friend by Dan Santat (2014)

- Crenshaw by Katherine Applegate (2015)

Part of a series by Pam Conrad about wooden people.

PYGMALION AND MODERN JOURNALISM

After the 2016 American Election, with my feeds full of Trump news interspersed with the odd grim images from my earthquake wracked hometown, I was glad to come across a positive article for a change — a biographical piece on a woman called Margaret Hamilton: The pioneering software engineer who coded humans to the moon. I’m going to spend the next four years reading about women and people of colour, I had already decided.

So I read the article and soon came across two full paragraphs not on Margaret herself but Professor Lorenz, the man behind the woman:

Professor Lorenz was one of the people who most inspired Hamilton throughout her life. He taught her a lot about software and gave her freedom to experiment with new ways of doing things.

Hamilton said: “Lorenz loved working with his computer and he would share with me his computer-related experiences and what he had learned from them, for which I was most grateful. Known as a genius by his colleagues, his humility stood out and he was one of the nicest people I have ever known.”

This seems fine, right? I’m sure Professor Lorenz was indeed a great mentor.

That said, when was the last time you read a biographical piece about a man with the achievements of Margaret Hamilton, wherein not the man himself is called a ‘genius’, but rather the wo/man behind the man.

Margaret is rendered passive here. Professor Lorenz gave her freedom.

This is something that regularly happens to women. Her agency is diminished. She is instead the product of a man.

I’m aware that much of that is quoted from Margaret herself, who sounds like she may be prone to typically feminine self-deprecation.

Mind that kind of writing which minimises a woman’s achievements while elevating the men in her periphery.

Another example is Hypatia.

Hypatia (c.355–415) was the first woman known to have taught mathematics. Her father Theon was a famous mathematician in Alexandria who wrote commentaries on Euclid’s Elements and works by Ptolemy. Theon taught his daughter math and astronomy, then sent her to Athens to study the teachings of Plato and Aristotle. Father and daughter collaborated on several commentaries, but Hypatia also wrote commentaries of her own and lectured on math, astronomy, and philosophy. Sadly, she died at the hands of a mob of Christian zealots.

Mental Floss

In sum, when writing about high-achieving women, be careful not to elevate the men around her in a way that actually overshadows the woman you’re aiming to highlight, even if you’ve found some self-deprecating quotes from the woman herself.

When reading about high-achieving women, keep an eye out for this almost invisible marginalisation and see it for what it is: a very long history of sexism, in which we cannot accept high-achieving women without attributing their successes to that of men.

Related to the Pygmalion principle of writing female biographies is the tendency to talk about the men and children in their lives more than talking about the woman herself:

Emilie Du Chatelet (1706–1749) was born in Paris in a home that entertained several scientists and mathematicians. Although her mother thought her interest in math was unladylike, her father was supportive. Chatalet initially employed her math skills to gamble, which financed the purchase of math books and lab equipment.

In 1725 she married an army officer, the Marquis Florent-Claude du Chatalet, and the couple eventually had three children. Her husband traveled frequently, an arrangement that provided ample time for her to study mathematics and write scientific articles (it also apparently gave her time to have an affair with Voltaire). From 1745 until her death, Chatalet worked on a translation of Isaac Newton’s Principia. She added her own commentaries, including valuable clarification of the principles in the original work.

Mental Floss

Sarah La Polla, literary agent (update: now freelance editor), points out on her blog that she sees this trope often in submissions:

Regardless of what happens in November, I hope Hillary Clinton’s candidacy will help make a trope I hate finally go away, and that is the Female Character Falling Ass Backwards Into Power. My literal examples are all TV-related:

- Veep, Male president resigns, female VP rises

- Commander In Chief, Male president dies, female VP rises

- Battlestar Gallactica, Everyone in the line of succession dies, female Sec. of Education becomes president (and is amazing, of course, but still)

Seriously, did no one think a woman could just, ya know, get elected? All by herself. Can’t we have even a fictional world where the people chose a woman voluntarily and not because a male option was dead? (But I digress…)

In not-so-literal examples, some trends I’ve noticed in submissions are:

- Female athlete who learned everything from her dad, who may or may not be the coach of her team too.

- Battle of the Sexes science fairs or class president elections.

- Propelled into the plot because of a missing father.

- Propelled into the plot because her father is the doctor/detective/scientist directly involved in the story.

In each of these stories, the girl is in the shadow of a more powerful man, and then — and only then — can she find her inner strength. It takes an “anything you can do, I can do better” approach to feminism that feels outdated.

Another gendered Pygmalion effect in journalism is noted below, in reference to Dr Oz and Dr Phil both saying highly unsympathetic things in close succession in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic:

“A Perfect Relationship”, the short story by Irish writer William Trevor, is a revisioning of the Pygmalion myth.

Header image: J.C. Leyendecker- the toy maker