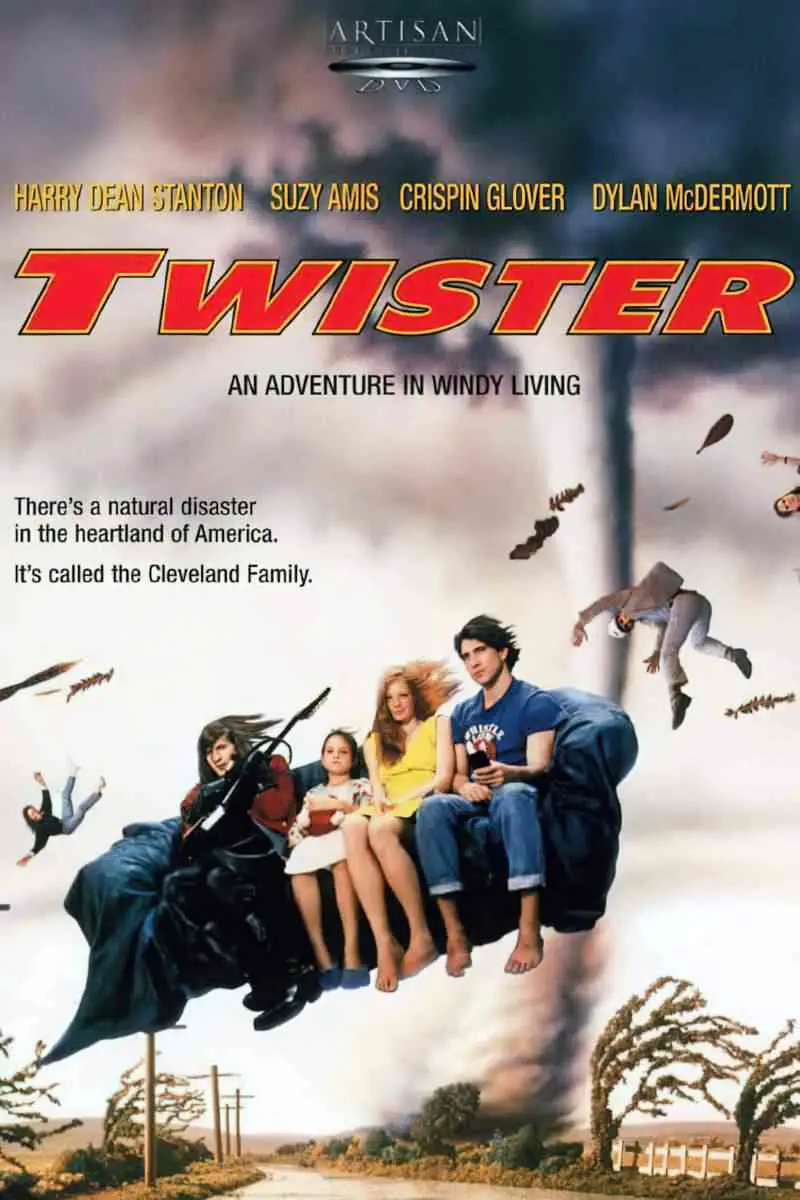

“Yours” is a 1982 short story by American writer Mary Robison. The year before The New Yorker published this short story, Robison published a novel called Oh! which was adapted for film in 1989. The film is called Twister. I don’t meant the late 90s blockbuster but a domestic drama set during a cyclone.

As for “Yours”, this is a very short story, so won’t take long to read. But you’ll probably want to read it again right away. Otherwise you may be left wondering what it’s all about, especially regarding the significance of the pumpkins.

THE PUMPKIN AS SYMBOL AND MOTIF

The pumpkin is clearly a motif. What’s the difference between a symbol and a motif? Symbols are more universal. They tend to stand for the same sorts of things across different stories, and even across time and culture. Motifs work like symbols, standing in for something else, but they are specific to the work of art at hand.

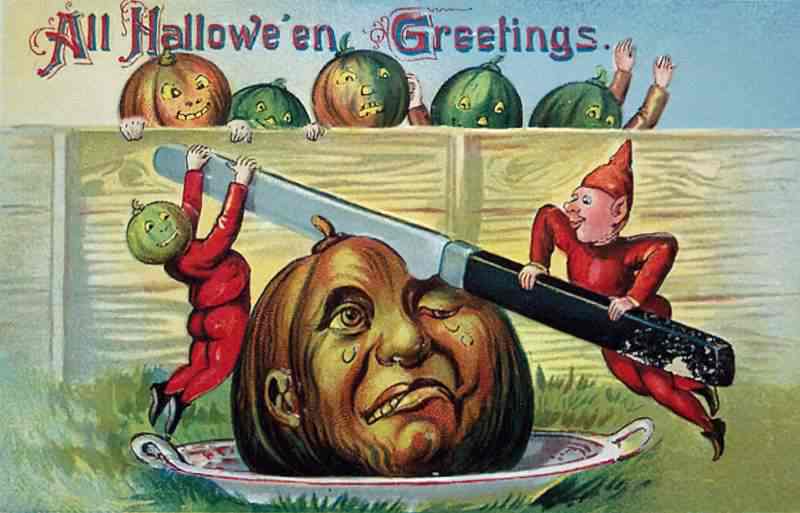

So what do pumpkins symbolise, generally? Hallowe’en, for Americans, and increasingly for the rest of the world. (Here in Australia kids are starting to Trick or Treat, even though Hallowe’en happens in spring.)

Pumpkins are also sometimes a sexual symbol. (What isn’t?)

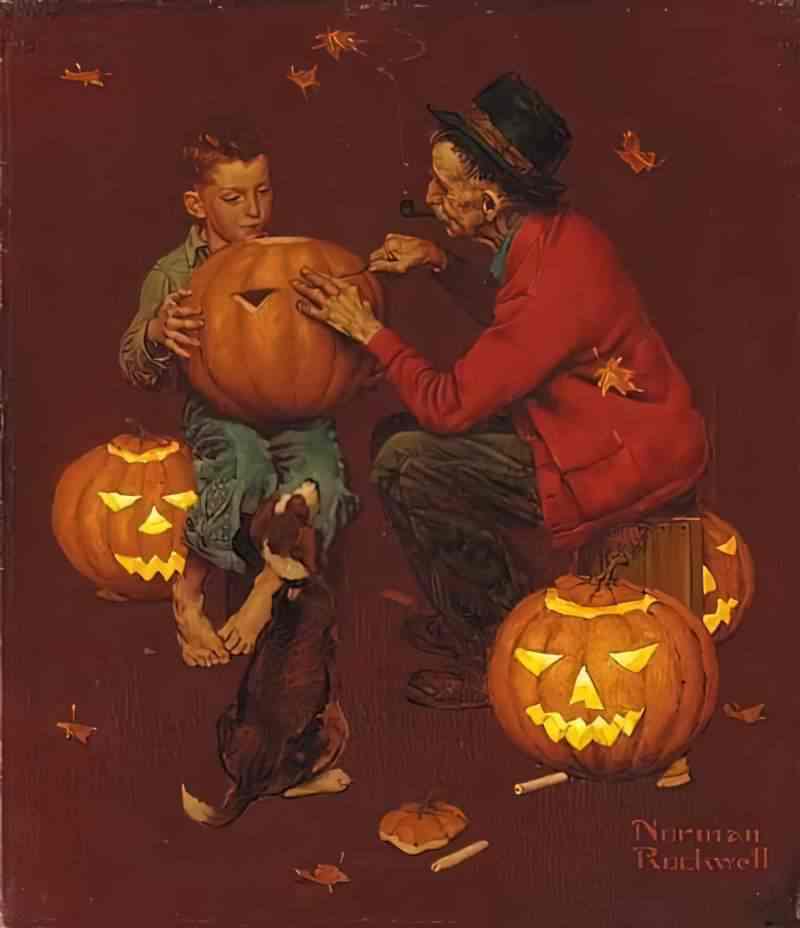

Mary Robison’s short story is set around Hallowe’en, so the story utilises the Hallowe’en pumpkin as part of the plot. But these carved pumpkins are doing more than simply establishing a Hallowe’en setting. Let’s take a closer look.

SETTING OF “YOURS”

PERIOD

The story was published in 1982 and seems to be set around that time also. Details such as the Renault and the Hepplewhite desk show that one or both of them have money, but this is an antique piece. George Hepplewhite 1727-1786 became one of the top English furniture designers of the 18th century. I’m imagining a house decorated from an earlier era.

The antique furniture is a nod to kairos rather than chronos. (A timeless story rather than one which wouldn’t exist if the era were different.)

Traditionally at Hallowe’en (All Hallows Eve), gourds, pumpkins, squash and turnips were carved and a candle put In to keep the harvests safe. This was to scare whatever would destroy them. Children carried these around the fields. They were displayed on window sills to reflect and scare away evil spirits. People also dressed in scary costumes, again to frighten those evil spirits. (We’ve kept the tradition of carving pumpkins.)

DURATION

The story happens over the course of an evening, in the time it takes to carve a number of Hallowe’en pumpkins. I find it interesting that they work through the night until one A.M. It is dark when Allison calls it a day.

All the neighbours’ lights were out across the ravine.

“Yours”

Like seasons, the day, too, metaphorically follows the course of a lifetime. The early hours are the death hours. Note that Allison is the one who suggests they turn in. In the near future, it will be Allison who makes the decision to let go. Clark must simply go along with Allison’s situation.

LOCATION

Virginia, America. The house looks out across a ravine.

I’m reminded of another American short story which takes place next to a giant geographical crevice: “The People Across The Canyon” by Margaret Millar.

When stories happen in the vicinity of ravines and crevices this is often a symbol of miscommunication. I mean, all stories include miscommunication. But some stories foreground it. This is one of those stories which foregrounds a miscommunication.

ARENA

This story could easily be adapted for stage as it takes place between the driveway and the bedroom of a single house. Sometimes when the stage is this small it can feel claustrophobic. A good example of a claustrophobic house setting is the one from August: Osage County (a stage play adapted for film).

MANMADE SPACES

Allison and Clark live in a comfortable, well-furnished house. It’s important to know Clark is financially secure, because this means there’s money at stake in the will. If he were destitute, the married daughter may have less to say about the new young wife.

NATURAL SETTINGS

When we meet Clark, he is on the verandah, which is as close as this couple get to enjoying nature. This is the suburban version of nature. Verandahs and porches come into their own around Hallowe’en, as they are now the focus of decoration.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

This refers to the story’s position on the hierarchy of human struggles. We don’t know what’s going on in the wider world of the story. This couple is in a cocoon. They arrive on stage in statu nascendi. The theme of life and death transcends any political significance of early 1980s America.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

Perhaps because they haven’t known each other long, this odd-couple are miscommunicating. It’s clear to us by the end of the story that they won’t have time to build a more intuitive relationship. Clark says something kindly meant but fails to communicate what he means.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

ALLISON

Allison is 34 years old and four months ago married a 78 year old doctor. The author gives us a detail about Allison which asks us to fill in some gaps: We are told she wears a wig.

We are also told that she is tall, and shares many features with her husband. At first I wondered if Allison is a visibly trans woman. This story is set in a time when facial feminisation surgeries weren’t a thing. (The very first was pioneered in 1983.)

But no, I’m on the wrong track. We learn she is ill, and deduce she is undergoing treatment for cancer. Now I must re-vision the opening line:

Allison struggles away from her white Renault, limping with the weight of the last of the pumpkins.

“Yours”

THE (IN)SIGNIFICANCE OF CLOTHING

She wears practical clothing. We all tend to look at clothing, especially women’s clothing, and read something of their personality into whatever women are wearing. Since Allison wears practical, durable clothing, we are to take from this fact that she has a practical and durable personality.

SLEIGHT OF HAND

I had imagined Allison carried massive pumpkins from the car to the verandah. Now I imagine regular sized pumpkins, but carried by a woman whose disease saps her strength. This is an example of delayed decoding.

Robison pulled a literary sleight-of-hand. When we think of a wife in her 30s and a husband in his 70s we think of a man near death, cared for by a robust and healthy young wife. In this story, however, it is the young woman who will require palliative care from her husband, not the other way round.

CLARK

The first thing we learn about Clark is that he is the sort of man who might carve Surreal (or grotesque) pumpkins for little kids. He is an internist. Internist doctors treat adults and specialise in the internal organs. When Allison and Clark ‘gut’ the pumpkins, Robison uses the language of the body. I suspect Allison finds Clark ‘gutting’ pumpkins more grotesque than had he not been an internist by profession. She can’t help thinking of human flesh, at a time of year which celebrates the grotesque.

We also learn that Clark hasn’t wanted their maid to make him supper. What’s the reason for his not wanting supper? Perhaps the “card” from his daughter has robbed him of an appetite. Robison is asking us to fill in many narrative gaps.

In contrast, Allison finds it funny. Perhaps Allison hasn’t met the daughter. If so, this would explain why there’s no love lost between them.

Clark is a ‘Sunday watercolour painter’ as well as a former internist. After four paragraphs my mind has (rightly or wrongly) filled in some gaps to the point where I like this elderly man a lot.

CLARK’S MARRIED DAUGHTER UP NORTH

The unnamed daughter has sent a passive-aggressive birthday note to her father including a gift check signed Jesus H. Christ. (This renders the check unbankable.)

In fact I fell into the same trap as this daughter.

I believed the older man probably married a much younger wife partly to look after him in his autumn years. But no, we now learn, if anything, it’s the other way round. Perhaps Clark even met his wife because she’s dying of cancer. Perhaps he has married her as a kindness because she has worked in childcare all her life on a low income and has insufficient health insurance.

I believe the author intended for me to fall into the same mental trap as the daughter. This is an example of successful subversion.

I just used the phrase ‘in his autumn years’, which links to the Hallowe’en setting. Seasons are heavily symbolic. Fall/autumn correlates to the years leading towards a wintry death.

One brief acrostic poem for each letter of the alphabet from acorn to zero follows the fall season from end of summer to chilly conclusion.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “YOURS”

PARATEXT

Why is the title called “Yours”?

Yours feels like a sign off for a letter. This story feels like a 35-year-old woman signing off from life. But I’m sure there are other valid interpretations as well.

“Yours” as in “your pumpkin carving is clearly the more superior”. That works too, at the surface level of the plot.

SHORTCOMING

I designate Allison as the Main Character of this story. We follow her into the house, watch her open the mail, follow her onto the verandah.

DESIRE

Allison is about to die. Are characters about to die different in what they want from life? We’re frequently told that the terminally ill become better able to determine the important from the insignificant.

Allison’s surface desire: To carve some pumpkins for Hallowe’en. She doesn’t want to scare children with them. She just wants to engage in this annual ritual, possibly as part of her mental preparation for death. (Of all the annual celebrations, Hallowe’en feels the most apt for this purpose.)

OPPONENT

There are just two characters on stage, with the Outside Opponent setting the tone for the story, though she is “up north” and otherwise irrelevant.

Clark and Allison argue when Clark insists Allison’s carved pumpkins are better than his when, as the reader knows from the dissonant narration, is patently untrue. Allison now feels infantilised. Perhaps this insistence that something ‘is not as bad as it actually is’ is part of a pattern of communication between them.

Perhaps the retired doctor’s reassurance was highly attractive in the beginning, when it was possible Allison would make it through the cancer. But things have changed now, as the reader is about to find out. No amount of pacifying will suffice, however kindly meant.

PLAN

A vigil is a time for families to gather together, sometimes in a home setting, to mark the transition of death in the presence of their deceased loved-one.

When Allison arrives back on the verandah with ‘yellow vigil candles’ I now understand that this ritual with the pumpkins is ostensibly a Hallowe’en ritual but is in fact a pre-death ritual. Allison is lighting candles in preparation for her own demise.

“You’re wrong,” Allison tells Clark. “You’ll see when they’re lit.”

“Yours”

In short stories especially, there’s a separate dialogue track at work behind the dialogue on the page. In this case, Allison’s dialogue also tells Clark, “There’s nothing you can say to persuade me that everything is going to be fine. I’m going to die. You’ll understand this when I am finally dead.”

When Allison says, “We’re exhausted. It’s good-night time,” she doesn’t mean sleep. She means death.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Sometimes a short story turns completely on a single sentence:

In her bedroom, a few weeks earlier in her life than had been predicted, she began to die.

“Yours”

Although this is the unseen narrator speaking to us, the straight-forward language of this sentence feels like psycho narration from the pragmatic and straight-talking Allison. We are now firmly inside Allison’s head.

ANAGNORISIS

But then the narrative camera switches to a different scene. Clark is ‘at the telephone’. Is he speaking into the telephone, or is he simply nearby? He has ‘a clear view out back and down to the porch’. The phrase ‘clear view’ could be a synonym for Anagnorisis.

But what has he understood? The wisdom he’d like to impart to his new wife feels wholly disconnected from what came before.

He wanted to tell her, from the greater perspective he had, that to own only a little talent, like his, was an awful, plaguing thing; that being only a little special meant you expected too much, most of the time, and like yourself too little. He wanted to assure her that she had missed nothing.

“Yours”

The reader now realises that Clark didn’t genuinely believe Allison’s carved pumpkins were more adroitly carved than his. He ham-fistedly tried to impart this wisdom by accidentally infantalising her with a patently untrue empty compliment. Sometimes what we say in words is nowhere near as nuanced as the idea in our head. Literature can help with this, putting our more subtle thoughts into words for us.

NEW SITUATION

Clark was speaking into the phone now.

“Yours”

The author never lets us know who Clark is speaking to. Do you have any ideas?

Knowing something of how stories work, I believe the person on the other end of the line has already been mentioned in the narrative. (Western narratives work like this. Eastern storytellers don’t worry so much about introducing early characters to be used later.)

I believe Clark is calling his adult married daughter. After receiving the angry, sarcastically signed cheque, he has decided to inform his daughter that no, he has not married a young gold digger who will cheat the daughter out of her inheritance. In fact his new wife will die before him, and after working his whole life in a caring profession, this new marriage affords him one last chance to care for another human being, while he still can.

This is a man who devotes himself to others. While Allison signs off with “Yours”, Clark is saying “I’m yours”.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

A paragraph Tim Kreider wrote in an essay reminds me of the widom Clark hopes to impart to Allison (really the reader) in “Yours”:

One of the most pitiable things about Joseph Merrick, the “Elephant Man,” was his undisfigured arm —“a delicately shaped limb covered with fine skin and provided with a beautiful hand which any woman might have envied” — a glimpse of the man he was meant to be, all but smothered inside the aspect of a monster.

Tim Kreider, “Bad People”, We Learn Nothing

When we carry around a shadowy, imagined version of the person we think we’re meant to be, this can be a heavy burden.

RESONANCE

This short story has been an interesting example of a short narrative which

- Subverts any preconception I brought to a story about an elderly man with a young wife.

- Spends most of the story talking about death without actually talking about death.

- Uses the final two paragraphs to switch into the head of the other character and impart wisdom which is a carefully narrated version of the failed communication exemplified above.

revisitING the pumpkin motif

Instead of talking about death, Allison and Clark busy themselves with pumpkins.

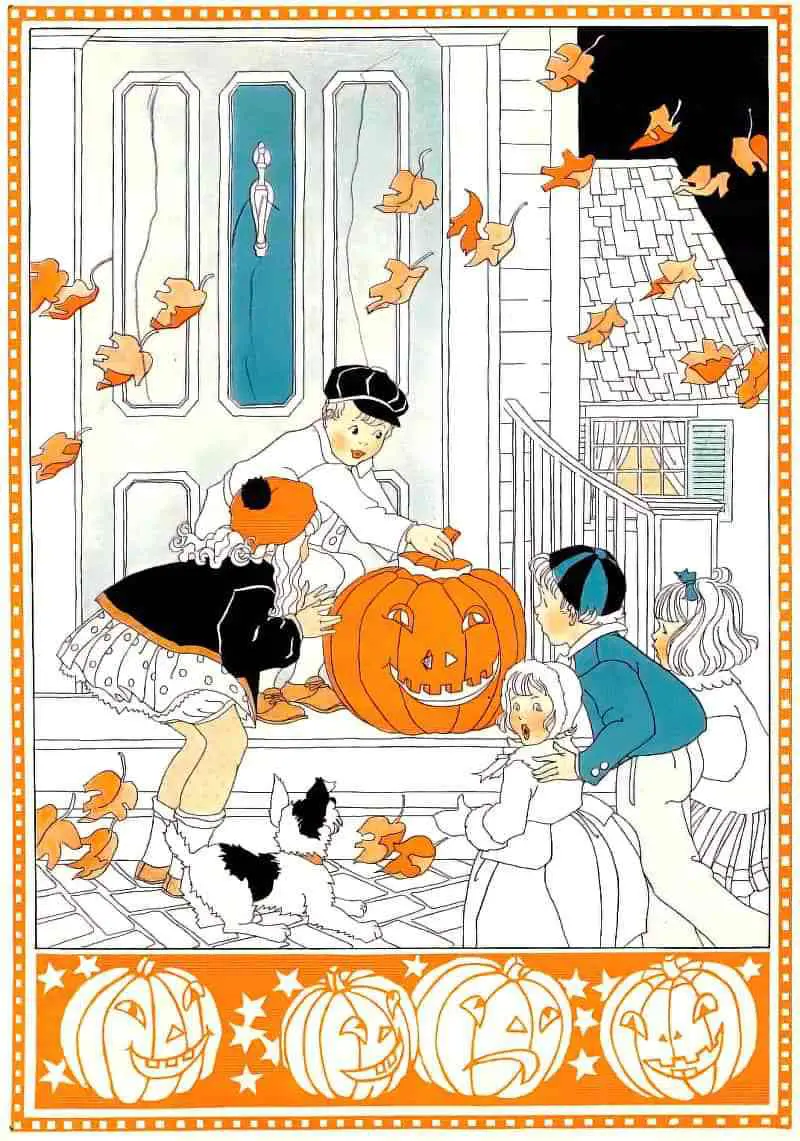

The European and North American tradition of carving pumpkins relates to the Christian idea of purgatory and the Festival of the Dead. Clearly, there’s a pre-existing connection between pumpkins and death around the Hallowe’en tradition. The writer is tapping into that.

But what might we take from the carved faces in particular?

Their carved features were suited to the sizes and shapes of the pumpkins. Two looked ferocious and jagged. One registered surprise. The last was serene and beaming.

“Yours”

Are these faces standing in for the various stages of grief? At first we all realise we’re going to die and we feel ferocious and jagged. At some point comes surprise. The ‘serene’ and ‘beaming’ part (hopefully) comes with the understanding that there’s nothing more to worry about.

MORE PUMPKIN ILLUSTRATIONS