“Psychology” (1919) is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, redolent with sexual tension which unexpectedly morphs into something else at the end. As expected from the title, the bulk of the story comprises a character’s interiority. After first setting the mood, Mansfield gets right into a woman’s feelings. Yet do we feel we know her? We must read between the spaces, what I call ‘Mansfield Gaps’. Everyone fills the gaps differently in a lyrical short story; this is my interpretation.

Katherine Mansfield liked to explore the theme of retaining one’s individuality. Characters seem terrified of losing themselves, of being subsumed by the roles expected of them. They wish for individuality. Mansfield’s stories, when taken as a whole, show that there are many pitfalls in love.

“Psychology” is an exploration into the emotional variability that goes hand in hand with intimacy. This variability is also pronounced in “The Swing of the Pendulum“, “Taking The Veil” and “The Singing Lesson“.

Fear of Engulfment

This is all related to what commentators have called Fear of Engulfment. An excellent example of a Fear of Engulfment story is “The Frog Princess“, in which a young woman is terrified of being trapped by matrimony and the ensuing (forced) pregnancy. This is a fear specific to people with child-bearing capacity, and many stories have cropped up to try and assuage this fear, or to persuade young women that everything will be all right, or at least, that they are not alone in this particular fear.

Is “Psychology” a Fear of Engulfment story? Quite possibly. A woman of reproductive age risks much in an era lacking reliable birth control, let alone social welfare payments for unwed mothers. Then there’s the intense social ostracisation.

Safer instead to develop a taste for The Erotics of Abstinence, replacing the sensual pleasures of sex with that of cake, augmented with a nice cuddle with your Auntie Virgin neighbour.

What did Katherine Mansfield think about human psychology?

If you really want to immerse yourself in how Katherine Mansfield viewed people, you probably want to read Principles of Psychology by William James.

William James was a ‘vitalist’ (alongside Henri Bergson). James believed that behaviour influences emotion. Previously it had been thought that a person’s emotion influences behaviour. Modern psychologists now know that emotion is more of an interacting cycle than a cause and effect kind of thing. James also came up with the phrase ‘stream of consciousness’, which describes modernist authors.

VITALISM, MODERNISTS AND CHARACTERISATION

Vitalism affected how modernist writers viewed ‘character’. Beforehand, the self had been understood in terms of a single transcendent ego, but modernists put it to their readers that ‘self’ was not only multiple, but also mutable. The self is not one single, never-changing thing. We change from moment to moment, as situations change. (Bergson added to this theory by making a distinction between superficial personality and deeper consciousness, which is exactly how storytelling gurus tell writers to create characters today.) This is partly what made Mansfield feel so modern. She challenged the ideology of the one true self (which we still see in much children’s literature today, as in ‘Be yourself’ stories). What does it mean to be yourself?

For Mansfield, the self is porous, caught between a virtual past and a virtual future. The self transforms moment by moment under the pressure of a past which breaks through into the present, and also by a future, essentially unknowable.

VITALISM, THE MODERNISTS AND TIME

In this way, vitalism also probably encouraged Mansfield to question the nature of time. She does all sorts of interesting things with time in her stories. She achieves The Overview Effect in “Prelude” and links children to the elderly. She picks symbols (e.g. the aloe in “Prelude“) for their interesting relationships with time. According to Henri Bergson, these separate selves don’t begin and end (I guess the would tip a personality into the realm of dissociative identity disorder), but each personality extends into another.

By this view it’s impossible to respond in exactly the same way to a single thing twice in succession. That’s because you’ve already had one reaction, and that first reaction will inevitably influence all subsequent reactions. It’s impossible to remain the same person, even from moment to moment. This is why so often Mansfield’s characters seem to be high on something one moment — the next downcast. e.g. Beryl in “At The Bay“, first viewing herself as a ‘lovely, fascinating girl’, then ‘All that excitement and so on has a way of suddenly leaving you’. (She has become aware of a nearby ‘sorrowful bush’.) Bertha in “Bliss” is another stand-out example.

Here, too, in “Psychology”, Mansfield’s unnamed playwright spends most of the story erotically charged at the thought of an impending sexual encounter… then suddenly shifts this eroticism into something else, directed at her older female neighbour who happens to drop by with flowers, and who is portrayed as a lonely, non-sexualised eccentric.

NARRATION IN “PSYCHOLOGY”

As many critics have agreed the stories in narrational parallax are [Mansfield’s] greatest. They attempt to epitomise the complicated and multifarious world within a narrow space from a variety of positions in order to create an image of an Impressionist atomistic modern world.

Apart from the juxtapositional parallactic method of using more than two perspectives, the stories “Psychology” and “The Daughters of the Late Colonel” are worth mentioning, because here only two equally important perspectives are contrasted with each other and sometimes even combined into a hazy, oblique one. The contrasting or juxtaposed perspectives are often roughly similar in their degree of limitation and reliability. In “Prelude” and “At the Bay”, Linda’s and Beryl’s visions are both deluded, in their fantasies and distorted views, although they themselves regard their visions as invested with superior wisdom or social or marital respectability. No perspective is authentic or authoritative, but through the narrator’s ironic modulation between various contradictory perspectives the image of the world is confused and blurred.

The world is depicted as fragmentary, momentary. It lacks a centre. The narrator is merely a medium through which reality flows into words. Mansfield’s ironic use of juxtaposition and contrast suggests that man’s experience of the world is multi-faceted and that is what marks this particular modulation as Impressionist in concept. In “At the Bay”, ironic narrative juxtaposition is employed, contrasting the preoccupations of the different characters, Kezia, Beryl, Linda, Mrs Fairfield, Stanley, and Jonathan with the minor ones. Juxtaposed to their restrictive views are the narrative intrusions, the detached philosophical and pastoral framing by the narrator, and occasional general narrative comments.

the author’s intention is not to focus the material in a certain single character and thus achieve unity of vision. She centers the material upon all characters and thus obtains a number of visions which exist not in a hierarchy but in an anarchy. The very sectioning of the stories indicates the author’s intentions of avoiding characterisation. Each section is a piece of coloured glass, and all the pieces exist together not in subordination but in juxtaposition. Out of each piece comes a shaft of light, the point of view of a character.

Yuan-Shu Yen

The effect of these ‘shafts of light’ by means of ‘the coloured glass’ suggest the different moments of great intensity, varying in significance according to the perspective from which they are seen. The reader is led to consider the preoccupations of the different characters, sometimes from both an oblique abstract view and sometimes from one which identifies closely with the characters’ situations. This is one of the impersonal and objective ways in which Mansfield was able to reconcile intrusive narratorial passages with the restrictive assumptions of Literary Impressionism.

Katherine Mansfield and Literary Impressionism by Julia van Gunsteren

SETTING AND SYMBOL WEB OF “PSYCHOLOGY”

FIRE AS EMOTIONAL STATE

As you read “Psychology”, notice how Mansfield uses fire as a metaphor for desire. The verbs could equally describe the feeling in a lover’s heart.

- He ‘came over to the fire and held out his hands to the quick, leaping flame.’

- ‘Just for a moment both of them stood silent in that leaping light.

- ‘She lighted the lamp under its broad orange shade’

- ‘Two birds sang in the kettle; the fire fluttered‘

- ‘That silence could be contained in the circle of warm, delightful fire and lamplight. How many times hadn’t they flung something into it just for the fun of watching the ripples break on the easy shores.’

COLOUR

Also take note of the colours in this story. Mansfield emphasised colour and related it to character mood. Colour is used for more than simply describing something.

Colour images fall into two basic categories:

- Images related to the visual experience of the character who sees it and

- Images which express in colour the atmospheric mood or their mental state.

Some commentators have said that Mansfield’s technique of describing colour maps directly onto pointillism, in which artists use short brush strokes to create a lot of dots and avoid blending, instead requiring the viewer to stand back in order to make out a scene. (Stand too close and all you’ll see are the dots.)

The orange of the lamp and the flame in this room, the red chairs, the blue of the chair and teapot — these are complementary colours. Why complementary? The playwright’s two types of intimate experiences are are equally complementary, meaning they are opposites but also perfectly matched.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “PSYCHOLOGY”

SHORTCOMING

If we crudely divide selves into public, private and secret, Mansfield was especially interested in the secret self, and in this story she uses the actual phrase ‘secret self’, showing that she must have thought in these terms.

Their secret selves whispered: “Why should we speak? Isn’t this enough?”

DESIRE

The exact nature of the ‘secret self’ is left to the reader’s interpretation. Clearly, from the body language, from the fact that a man is visiting a woman’s private rooms, checking they won’t be disturbed, these two are getting ready for some kind of erotic experience together.

But why does the playwright hold back? That part is left for the reader to extrapolate. I am taking the era into heavy account, as well as Mansfield’s own life. Biographers believe that Mansfield had at least one abortion. Penetrative sex with men was risky for almost any young woman living in a pre-birth control era.

It seems the playwright of “Psychology” wants an erotic experience with a man, but without the masculine, patriarchal, high-risk version of sex, which is almost certainly the kind he expects.

OPPONENT

The playwright and the writer are romantic opponents. He smiles in ‘a naive way’. Why naive? Perhaps he came for the transcendent experience with cake, not realising the playwright is getting far more out of this moment than high tea.

POTENTIAL, TRANSITIONAL SPACE

What does it mean to be a ‘romantic opponent’? Much has been said about the mind-meld that takes place in this particular story, referring to how two minds become one.

Donald Winnicott was an English paediatrician and psychoanalyst who came up with a concept known as ‘potential’ or ‘transitional’ space. At first I wondered why the man is talking about a little boy. Which little boy? (Is he into little boys…?) But no, commentators have gone into that.

…touch, very lightly, that marvel of a sleeping boy’s head… I love that little boy

Apparently the little boy is to be coded as a ‘symbolic object’. The (non-existent!) ‘little boy’ exists in the transitional space between the man and the woman. This space both separates and unites them. When the man imagines he touches the boy’s sleeping head, he sees it happening only inside his head. Touching but not touching. This is how Mansfield creates both distance and closeness between two characters at once.

NEIGHBOUR AS SECONDARY ROMANTIC OPPONENT

The virginal neighbour may not in fact be virginal. Mansfield’s style of narration moves in and out of a main character’s head — it’s up to the reader to decide which details are veridical fact and which are character interpretations. ‘Virginal’ is how the neighbour strikes her.

But this ‘virgin’ drops in with flowers quite often. In Mansfield’s other stories, for instance in “Carnation“, flowers are connected to eros, including between women. When we offer another person flowers we are encouraging them to enjoy a sensual experience, be it from colour, smell, texture of the petals. An offering of flowers feels almost like a check: “Are you capable of enjoying a sensual experience? How about one… with me? At some point? Maybe?”

Has the playwright already realised this about the neighbour? Doesn’t really matter. She realises it later, I think.

By the way, the violets, like the ‘little boy’ are thought to be another ‘transitional object’ which distance the two women as well as bringing them together. ‘Even the act of breathing was a joy’, she says. I have no idea what it’s like to live with tuberculosis, especially while being a smoker (as Mansfield was) but I can imagine Mansfield felt a special pleasure in easy breathing.

PLAN

It’s clear the playwright has invited the writer to her room, and made sure they won’t be disturbed (though she does have that neighbour inclined to pop in without notice). The playwright must trust this man sufficiently to respect her boundaries. He is not the ‘sexual conquering’ type:

For the special thrilling quality of their friendship was in their complete surrender. Like two open cities in the midst of some vast plain their two minds lay open to each other. And it wasn’t as if he rode into hers like a conqueror, armed to the eyebrows and seeing nothing but a gay silken flutter — not did she enter his like a queen walking soft on petals.

Nothing suggests this is a well-thought-out plan, but the playwright’s plan is this: She will enjoy the frisson of a man in her private room. She seems to want what these days may be called a queerplatonic relationship with the man.

Queerplatonic has been used to describe feelings and relationships of either/both a nonromantic or ambiguously-romantic nature, in order to express that they break social norms for platonic relationships. It can be characterized by a strong bond, affect, and emotional commitment not regarded by those involved as something beyond a friendship.

Aromantics wiki

“if you’d picture romance with taper candles over dinner, and sexual relationship as a queen bed, I would try picturing the queerplatonic as string lights over tea and a bunk bed with tin can-and-wire phones between them. The same, but not.”

Aromantics wiki

BIG STRUGGLE

The entire story is one long big struggle between desire and restraint. The playwright uses food as children’s books use food — as a highly sensuous experience, where other works use sex.

ANAGNORISIS

Mansfield tended to leave anagnorises off the page. They happened between the gaps.

In the gaps of “Psychology”, the playwright does seem to realise something, though in true modernist style, she probably doesn’t fully understand it.

The stupid thing was she could not discover where exactly they were or what exactly was happening. She hadn’t time to glance back.

She seems to realise that she can have a rounded and satisfying emotional-sexual experience with a combination of hot guy followed up with a cuddle from her virginal older female neighbour. She’s getting one type of erotic stimulation from the man, and another complementary (though completely different) sort of care from the neighbour.

On the page, it is the neighbour who realises something. “Then you really don’t mind me too much?” she asks showing that, until this moment of shared tenderness, she’d been doubting her value in the playwright’s eyes.

NEW SITUATION

Perhaps the playwright and the neighbour will forge a closer friendship after this beautiful embrace.

It’s also possible that once the playwright has come down from her erotic high, lit by her time with the man and seeping into her moment with the neighbour, the playwright will feel uncomfortable with the neighbour — who seems to want more — and shrink away. Earlier in the story she has compared herself to a snail, who retreats into its shell, so I think this extrapolation is equally likely.

BIRTH CONTROL

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by evolutionary psychologist Dr. Sarah E. Hill to talk about her new book, “This Is Your Brain on Birth Control: The Surprising Science of Women, Hormones, and the Law of Unintended Consequences.” They discuss the long history of scientific inquiry that ignores women’s bodies and minds, as well as what new research is telling us about birth control’s sweeping effects.

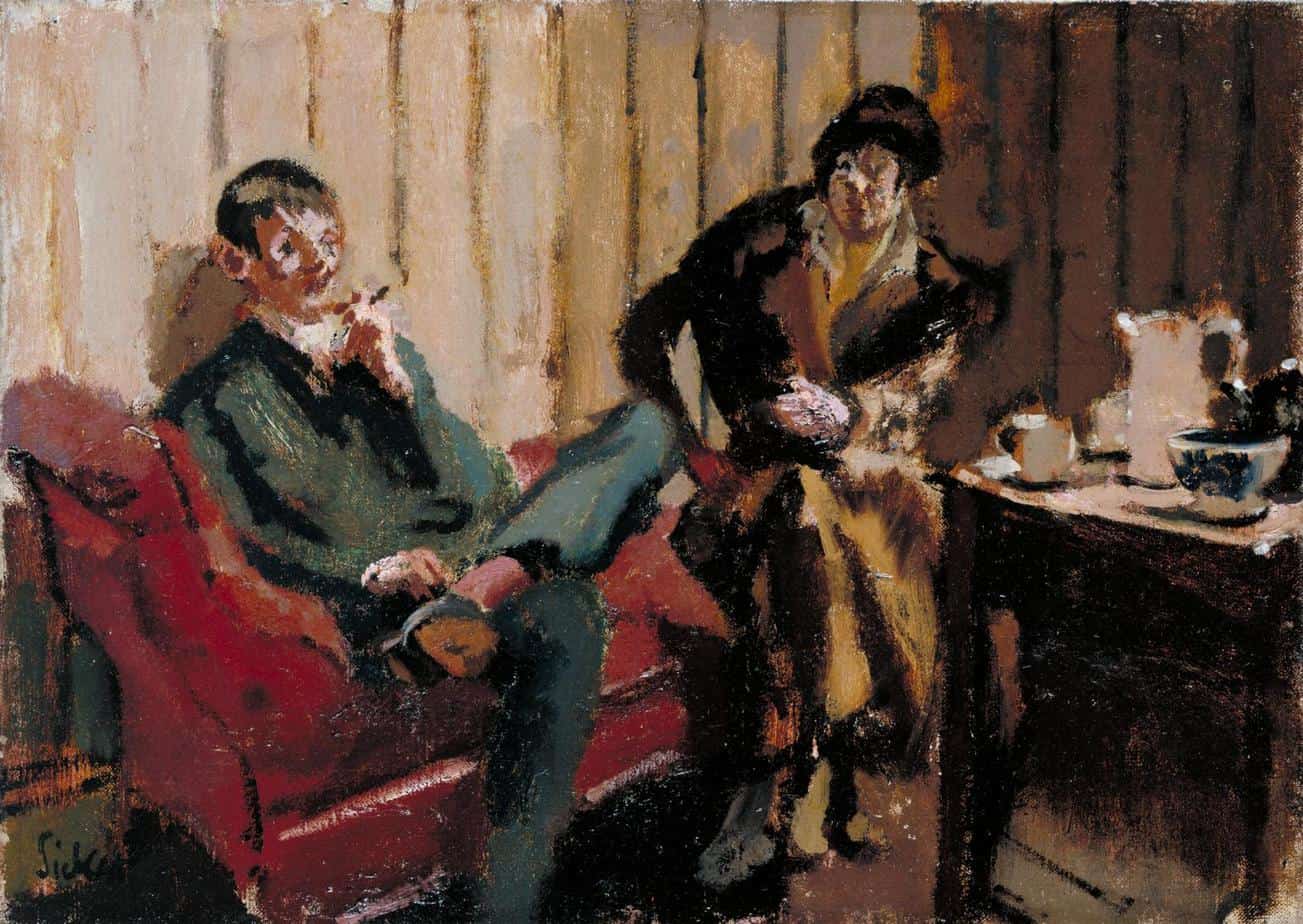

Header painting: Edwardian Interior c.1907 by Harold Gilman