How is hoarding treated in fiction, if at all?

In her short story “Free Radicals“, Alice Munro portrays a woman working through the recent loss of her husband.

First, the way friends react — helpfully and unhelpfully. Funeral arrangements, immediate aftermath.

Memories, both painful and beautiful, mixed in together to paint a portrait of a rounded life.

The lonely act of walking into rooms and finding him conspicuous by his absence.

Then, the following detail stuck out to me:

She did make up the bed and tidy her own little messes in the kitchen or the bathroom, but in general the impulse to take on any wholesale sweep of housecleaning was beyond her. She could barely throw out a twisted paper clip or a fridge magnet that had lost its attraction, let alone the dish of Irish coins that she and Rich had brought home from a trip fifteen years ago. Everything seemed to have acquired its own peculiar heft and strangeness.

Alice Munro, “Free Radicals“

Alice Munro must have observed that the recently bereft tend to hold onto things.

A few days before reading the story I listened to a completely unrelated interview between Kim Hill and Douglas Coupland. (“I Miss My Pre-Internet Brain”) Coupland happened to get talking about the psychology of hoarding.

Hoarding behaviours are often a way of dealing with trauma and grief. Hoarding tends to run in families.

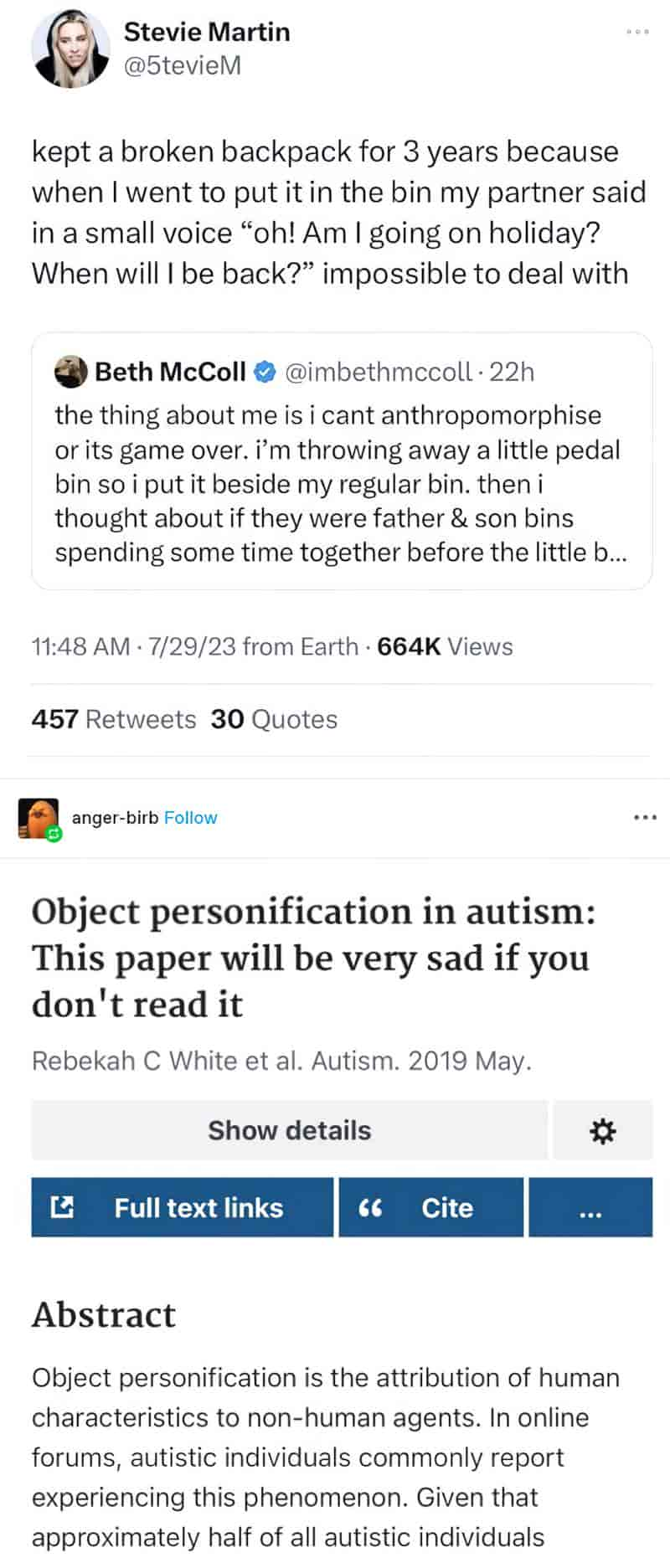

Anecdotally, hoarding disorder (HD) may have links to autism and other neuro-differences, though studies don’t tend to show this.

So far, HD seems most clearly linked to obsessive compulsive disorders behaviours rather than other forms of mental ill-health.

What I didn’t know before listening to Kim Hill and Douglas Coupland speak on it (at about the 27:30 mark): Certain medications can provoke hoarding behaviours. Coupland mentions a drug for Parkinson’s disease, which also treats restless leg syndrome. This leads to hoarding behaviour in some people. This is not widely known.

Also not widely known: The genetic link between restless leg syndrome and ADHD. I’m sure this all triangulates eventually. (I have all three in my extended family.)

Kim Hill says she’s not ‘hoardy’, but admits that most people don’t think they’re hoardy. Then someone comes round and points out your massive and totally reasonable collection of dishcloths.

Psychology has much to learn about hoarding and related psychologies. But one thing is clear: Hoarding is not a moral issue. A behaviour which can be provoked by medication, or quick and extreme loss, suggests hoarding disorder could happen to any of us. You can almost set your clock to it, Coupland says. “Eighteen to twenty months later [after the loss], hoarding kicks in.” Being self-aware, knowing that you have a predilection for hoarding, makes no difference.

And Douglas Coupland, sometimes accused of being a hoarder himself, counters the museum minimalist types with this: If you live in a white box, you’re just a different kind of hoarder. You’re simply hoarding space.

So what of the proliferation of reality TV shows which make a spectacle of hoarders and their houses? Why is there so much appetite for those shows? Does it say something terrible about our natural human voyeurism? Is it exploitation? Much has been said on this matter already, and I agree with it all, but what lessons might storytellers learn about the content people crave?

I believe it comes back to ‘glamour’, in one specific sense. The archetypically ‘glamorous’ place is the store that sells containers for keeping our stuff in. We walk into those stores and are immediately charmed by the idea that we, too, could be super organised, and this would improve our lives.

We love the hoarding shows because we look at that mess and we see how much better it could be. Just hire five skips, we think. Bleach the hell out of that place and it would look so much better. Audiences widely love Marie Kondo. We love building shows, home renovation shows, move to the country shows and even cooking shows, for the same deep-rooted reasons.

This desire to improve plays into a specific wish fulfilment: for order, for constant improvement, for the opposite of entropy. For safety. For this same reason I loved Little House In The Big Woods as a six-year-old. In the fictional Ingalls’ lives, things were constantly getting better. Log cabins were getting built, food was getting preserved for winter, ground was being covered.

Now, for storytellers to meet that need without real life exploitation.

RELATED

- Listen to Australian podcast All In The Mind for an episode on the psychology of hoarding. (There’s also a transcript.)

- The Weight Of Parental Love and Things And Time And “Help” is a post from Captain Awkward in response to a woman whose parent is hoarding.

- A Collection a Day: An Obsessive Homage to Order

I think the lack of acquisitiveness is, interestingly, a sort of old age thing. I have a houseful of possessions; I don’t want any more things. But when you were younger, you often wanted new things, yes indeed. You coveted a lovely new rug or you coveted something new for the kitchen. I don’t do that now because in a sense I’ve — I was going to say, “I’ve got it all,” but no, you can always have something that’s even better than what you’ve already got. But I seem to have lost that feeling of, “Ooh, I really just must have that,” whatever it was. It goes, which is something of a relief.

Penelope Lively, NPR Interview

“Where is the good knife?” If you’re looking for your good X, you have bad Xs. Throw those out.

Establish clear rules about when to throw out old junk. Once clear rules are established, junk will probably cease to be a problem. This is because any rule would be superior to our implicit rules (“keep this broken stereo for five years in case I learn how to fix it”).

Keep your desk and workspace bare. Treat every object as an imposition upon your attention, because it is. A workspace is not a place for storing things. It is a place for accomplishing things.

Less Wrong

- Do you hold onto a lot of items that have sentimental value?

- Do you have trouble getting rid of clutter?

- Do you get anxious about getting rid of things?

If you answered yes to any of those questions, today’s episode is for you. I’m talking about the science behind why it’s so hard to get rid of things sometimes–and what those things you hold onto say about you.

Don’t worry, I’m not going to try and convince you that you need to get rid of those things. Instead, I’m going to tell you what you can learn about yourself by looking at those things that you hold onto. Those items that you refuse to throw away or get rid of, say something about your self-worth.

Very Well Mind podcast

Very Well Mind podcast

- How clutter creates more stress

- The real reason we find it so difficult to part with items that get in our way

- How clutter can lead to feelings of shame

- How clutter affects so many areas of our lives, from our relationships to our finances

- How clutter affects your time

- Why your home doesn’t have to be completely organized

- How decluttering your space will make you happier and less stressed

- A step-by-step guide to decluttering one step at a time

- How to know if you have too much stuff in a room

- What to do with the stuff you aren’t going to keep

- How keeping too many sentimental things can keep us stuck in the past

- The best way to get started with decluttering your home

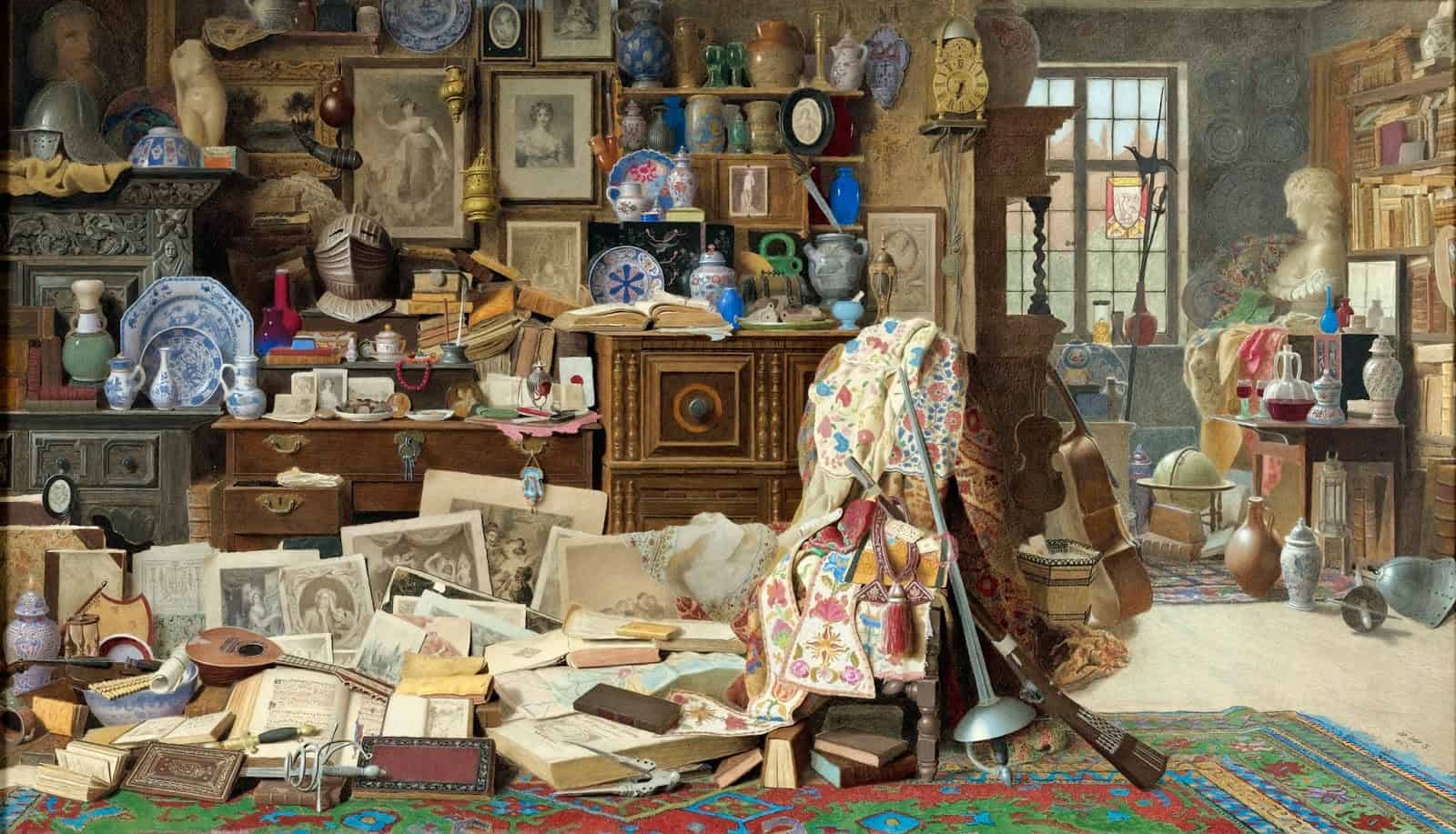

Header illustration by Benjamin Walter Spiers – Old armour, prints, pictures, pipes, China (all crack’d), old rickety tables, and chairs broken back’d Thackeray