The Princess and the Pea was first published in 1835, one of a handful of satirical, colloquial fairy tales in an unbound collection by Danish storyteller Hans Christian Andersen. The colloquial language didn’t go down well with critics at the time, who also didn’t appreciate that Andersen’s silly little “wonder tales” failed to convey a moral suitable for children.

It took another 11 years for English speakers to read this story in translation, but it wasn’t the same story at all. Translator Charles Boner didn’t pick up on Andersen’s satire. Or perhaps he did pick up on it, but didn’t find it funny. In any case, Boner (great name, huh?) did not simply translate Andersen’s tale, he changed the ending and left English readers with something quite different.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE PRINCESS AND THE PEA”

PARATEXT

Hans Christian Andersen’s original title is “The Princess On The Pea”, but the English title makes it seem almost as if the pea is a character in its own right.

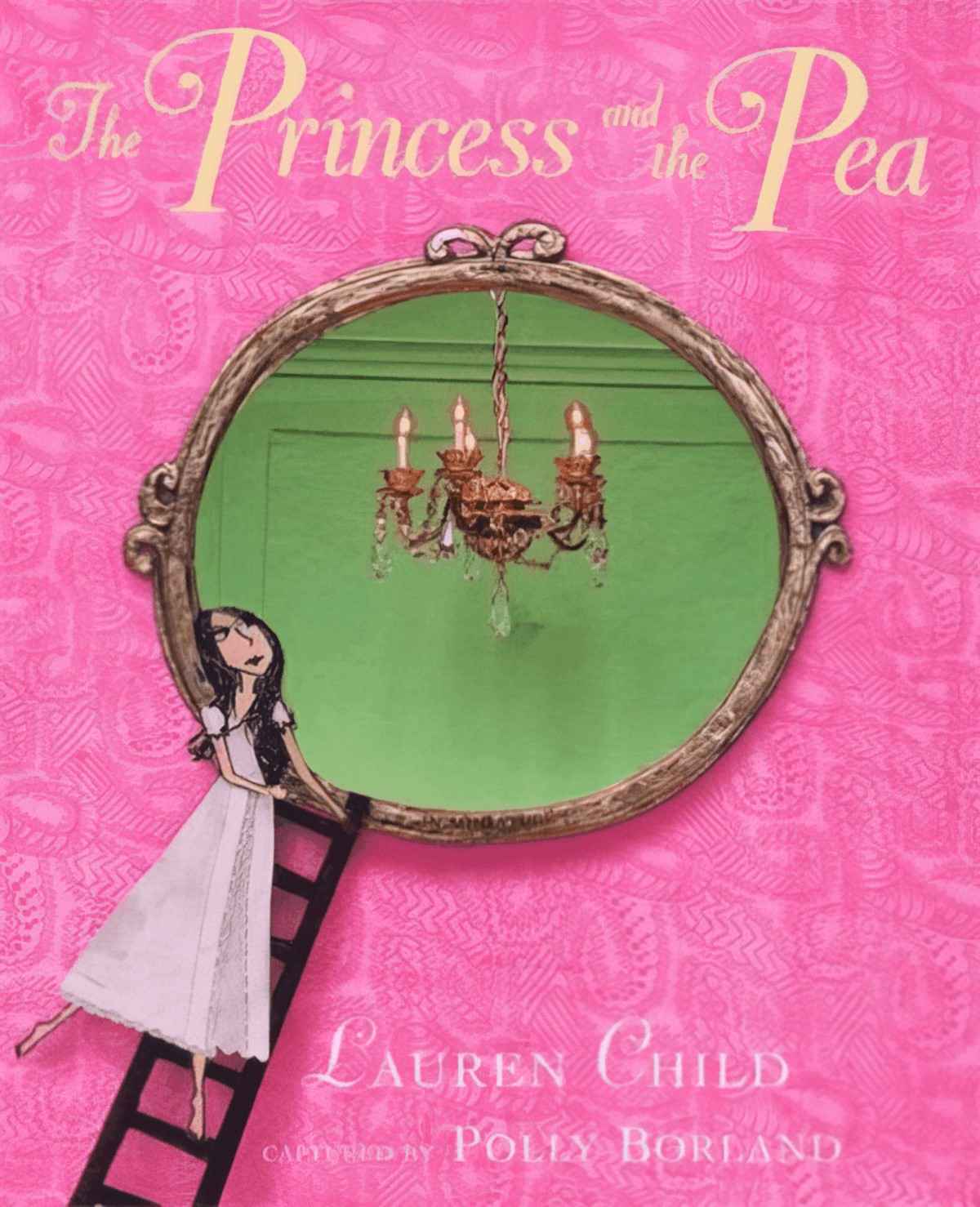

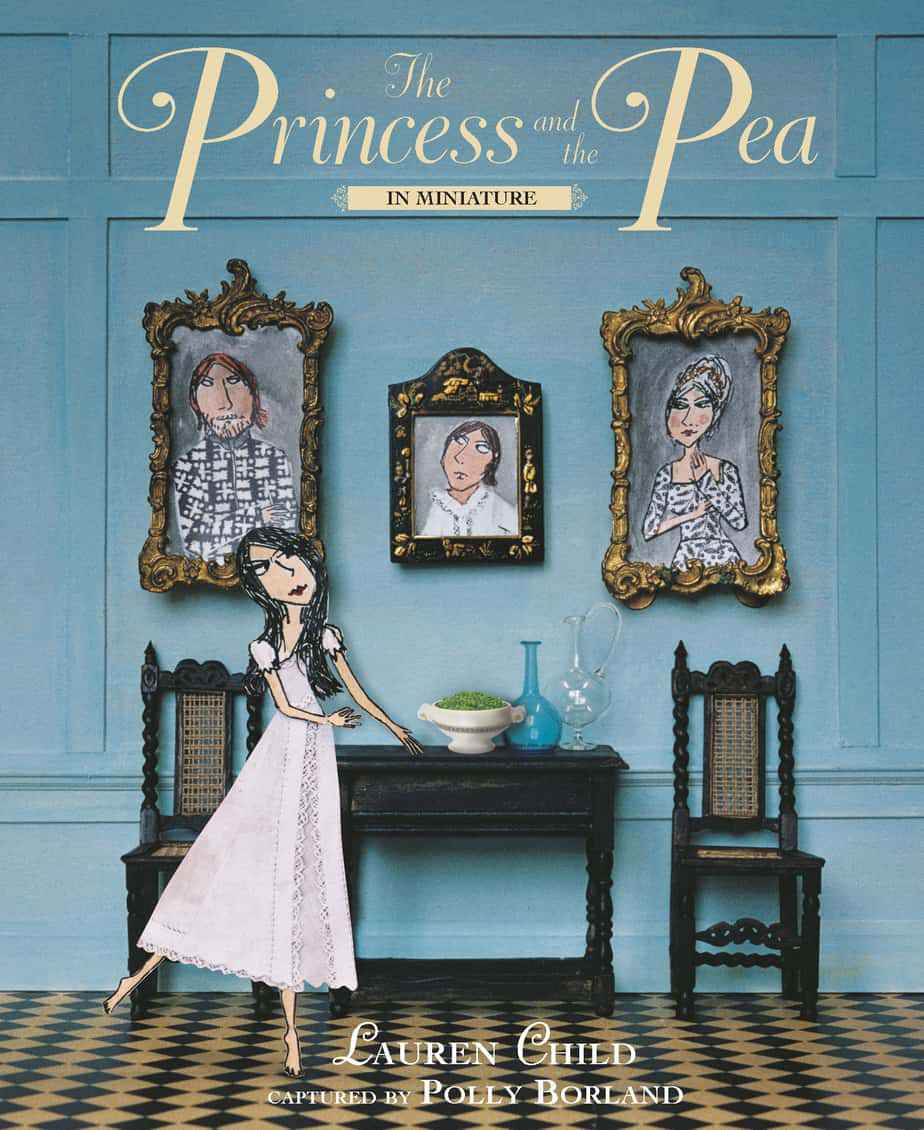

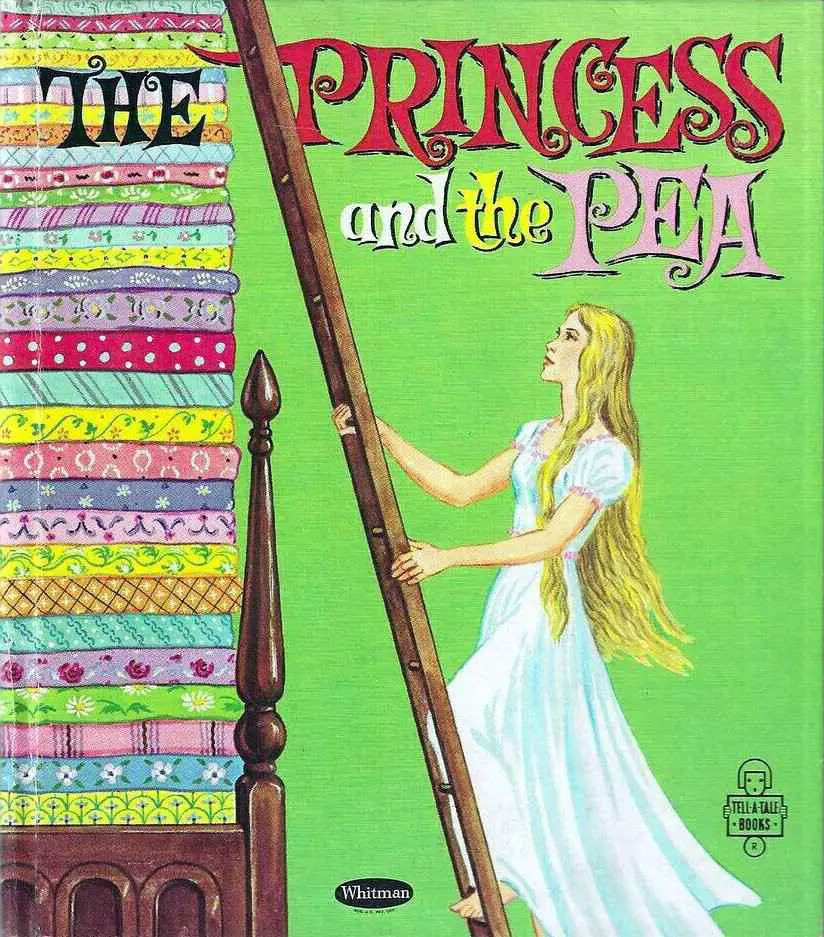

“The Princess and the Pea” is a literary fairytale written by a man, starring a boy who wants to get married and is a social commentary on class. The proliferation of pinks, purples and pastels on covers show that many contemporary publishers are marketing this tale at girls. (Don’t at me; marketers have been working on the pinkification of girlhood for decades.)

‘Do you write for boys?’

While girls are happier to read about boys, she is worried about why most boys are more reluctant to read books or watch films about girls.

“I don’t know if it’s just in our culture, or whether it’s a boy thing, that they find it very hard to pick up a book or go to a film if a girl is the central character,” she told BBC News.

“I don’t know where that comes from but it worries me because it makes it harder for girls to be equal.”

Lauren Child, BBC

I find it interesting that there are two covers of The Princess and the Pea as re-visioned by picture book giant Lauren Child, who said when becoming children’s laureate that one of her main concerns is how many parents do not consider her books ‘for boys’. I wonder if Lauren Child was concerned that a pink cover would repel boys (more likely repel adults, buying books for boys), and as a workaround, had the clout to ask for at least a blue cover to grace the shelves alongside?

SHORTCOMING

The Princess And The Pea is an example of a story with two main characters: One is the viewpoint character who frames the story of another character. Readers receive the story of the princess via the eyes of the prince, and also via the more proactive prince stand-in: his mother.

But since this is really the story of a community (or socio-economic class) the weakness belongs to the community as a whole: Namely, their own perceived tenuous grip on power.

Hans Christian Andersen had an interesting relationship with the ruling class. He felt he belonged up there, but was forever excluded. This didn’t stop him wanting to feel a part of it, which made him a keen observer. As an outsider, he could better see the ruling class for what they were. “The Princess and the Pea” is a comment on the ridiculous lengths the powerful will go to, in order to hoard power and resources for themselves. Aristocracy marrying other aristocracy is one way of holding onto power. But how do you know for sure you’re not marrying beaneath you? What if the other family is lying to you about their own wealth and social standing, all to secure some of your family’s loot? The more you have, the more you have to worry about.

Today we use a variety of words to describe the sensitivities of people who hoard resources and power. For example, the phrase ‘white fragility’ describes discomfort and defensiveness on the part of a white person when confronted by information about racial inequality and injustice.

DESIRE

The prince needs to find a marriage partner. Whether he actually wants to get married is another question. He does want to retain his social standing, so get married he must. His mother is more of a driving force than he is. It’s the mother who comes up with the plan.

OPPONENT

The Prince and Princess are each other’s romantic opposition, though the main opponents are the Queen and the young woman, who threatens to come in and replace her. There’s as much at stake for the Queen.

PLAN

The Queen places a pea under the many mattresses to check whether the intruder girl with princess pretensions will feel it or not. If she can feel it, she’s definitely a princess for real. Presumably the Queen herself was once a Princess, and knows what it takes to find one.

But what is the pea under mattresses a metaphor for, exactly? We go to so much trouble to signal which group we belong to, but no one spends more time (and money) in that pursuit than those at the top of the pecking order. In order to curate the accoutrements, clothing and manners of the most powerful class, one must actively reject those of the less powerful classes. Even when ensconsed inside the powerful classes, women hold the more precarious position, and so women must be especially careful to ‘act like’ it.

Women are then blamed for being too particular, of course. I don’t believe Andersen is making any gendered commentary here. He is commenting on class. The Prince of Andersen’s story is as fastidious about his woman as the Princess is of her bedding situation. I even wonder if Princesses are his orientation. Andersen’s biography comes into play here: Andersen was a gay man stuck living in a hetero-compulsory time and culture. I deduce the author would have himself been familiar with the experience of meeting plenty of beautiful, eligible women and finding none of them attractive (and not being able to explain in words why, because of the centuries-long hermeneutic injustice of deliberate LGBTQIA+ invisibility).

THE MATTRESSES

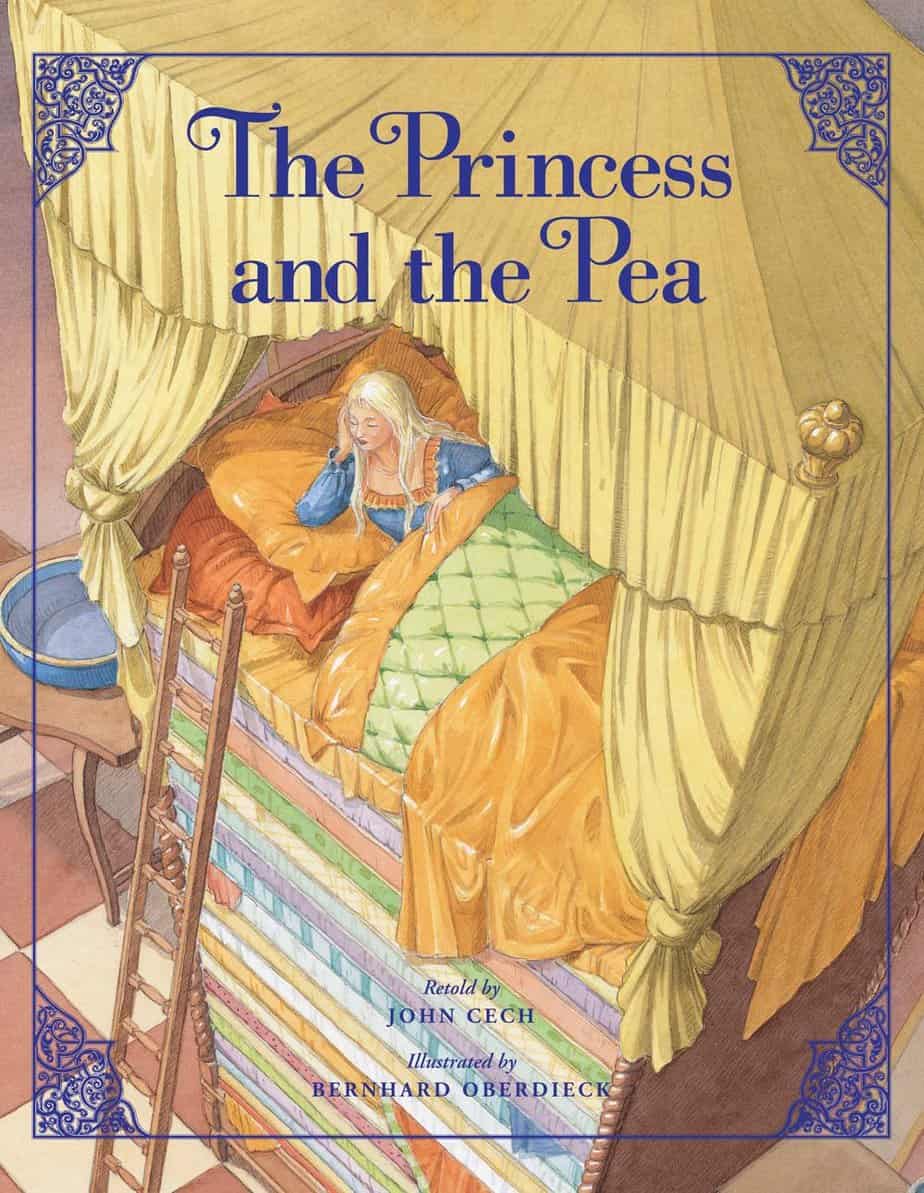

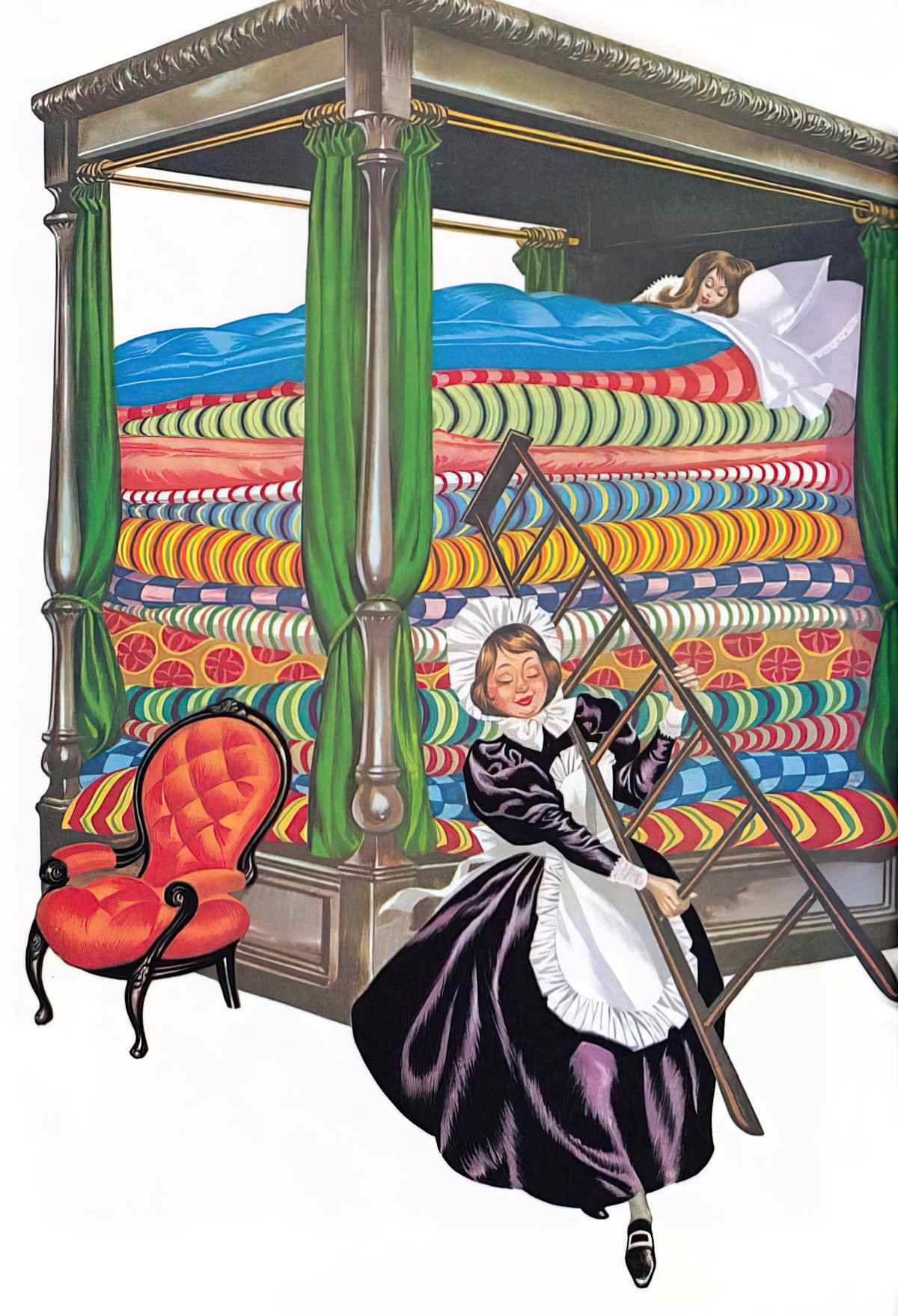

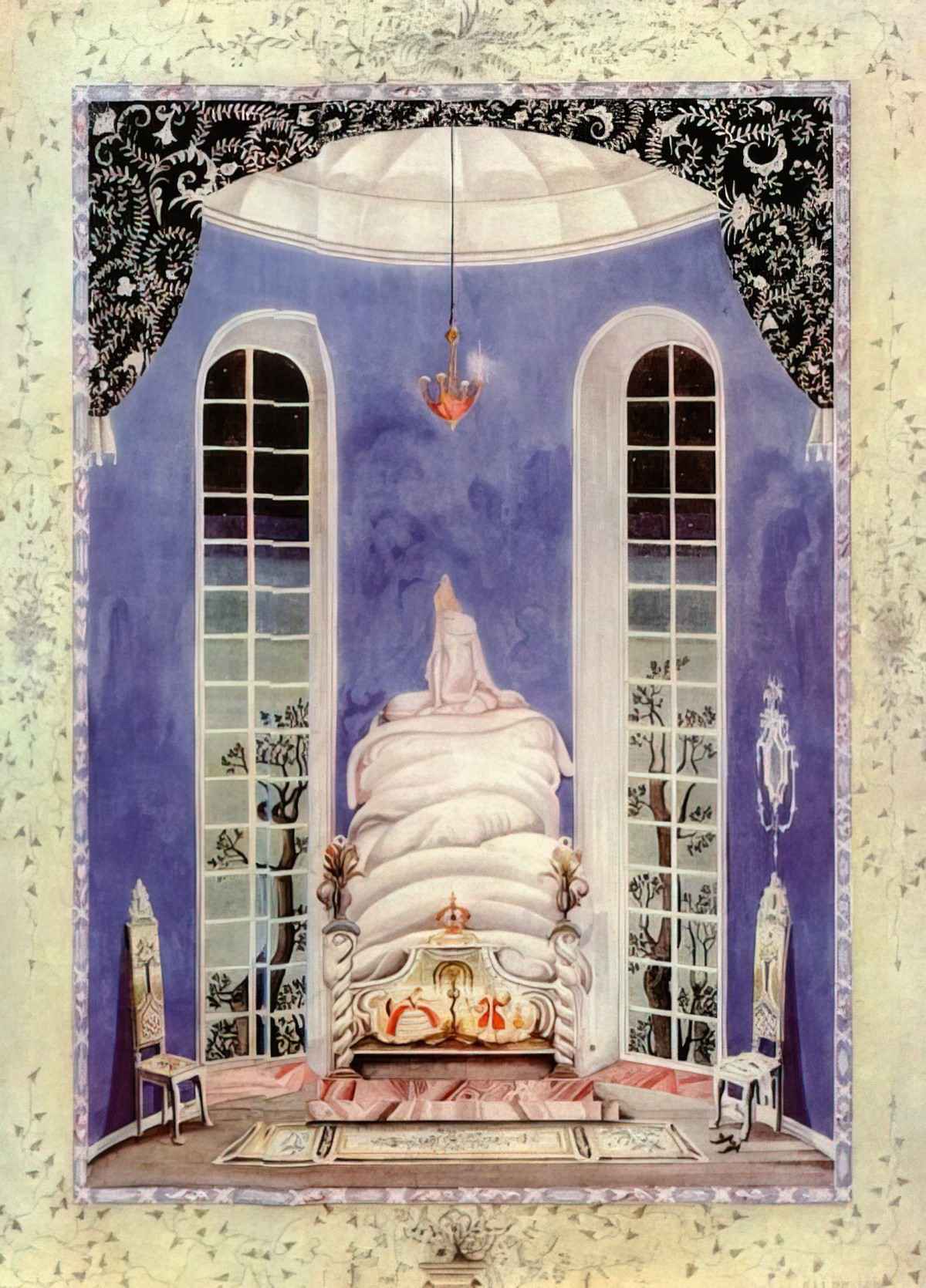

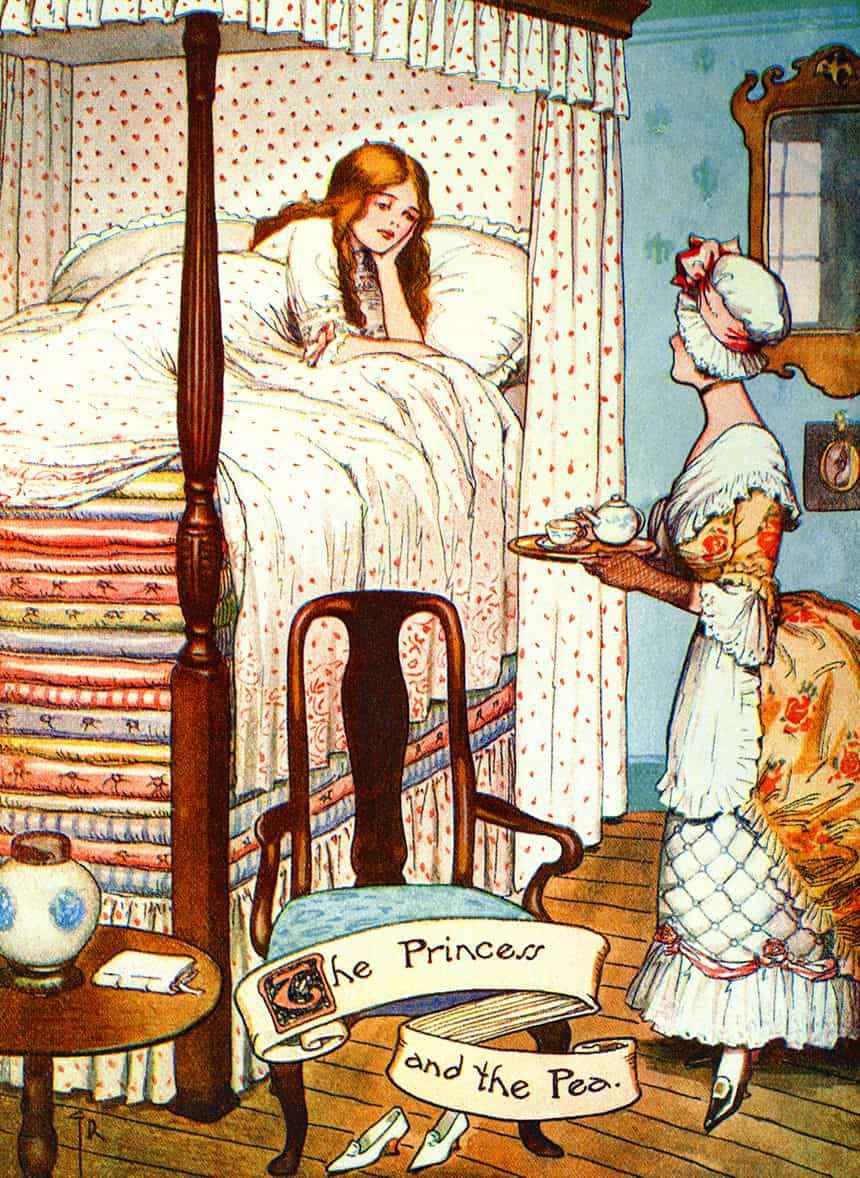

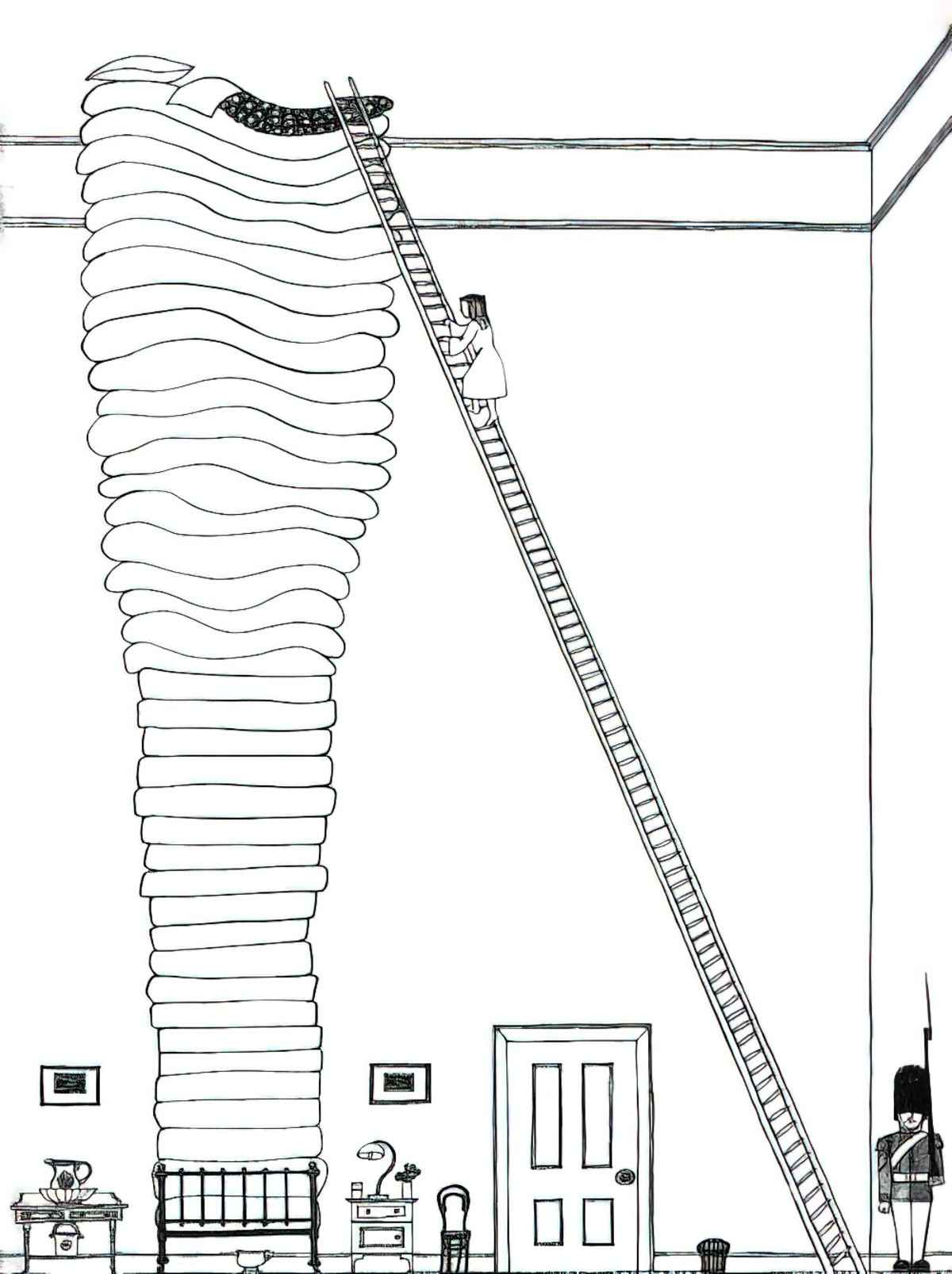

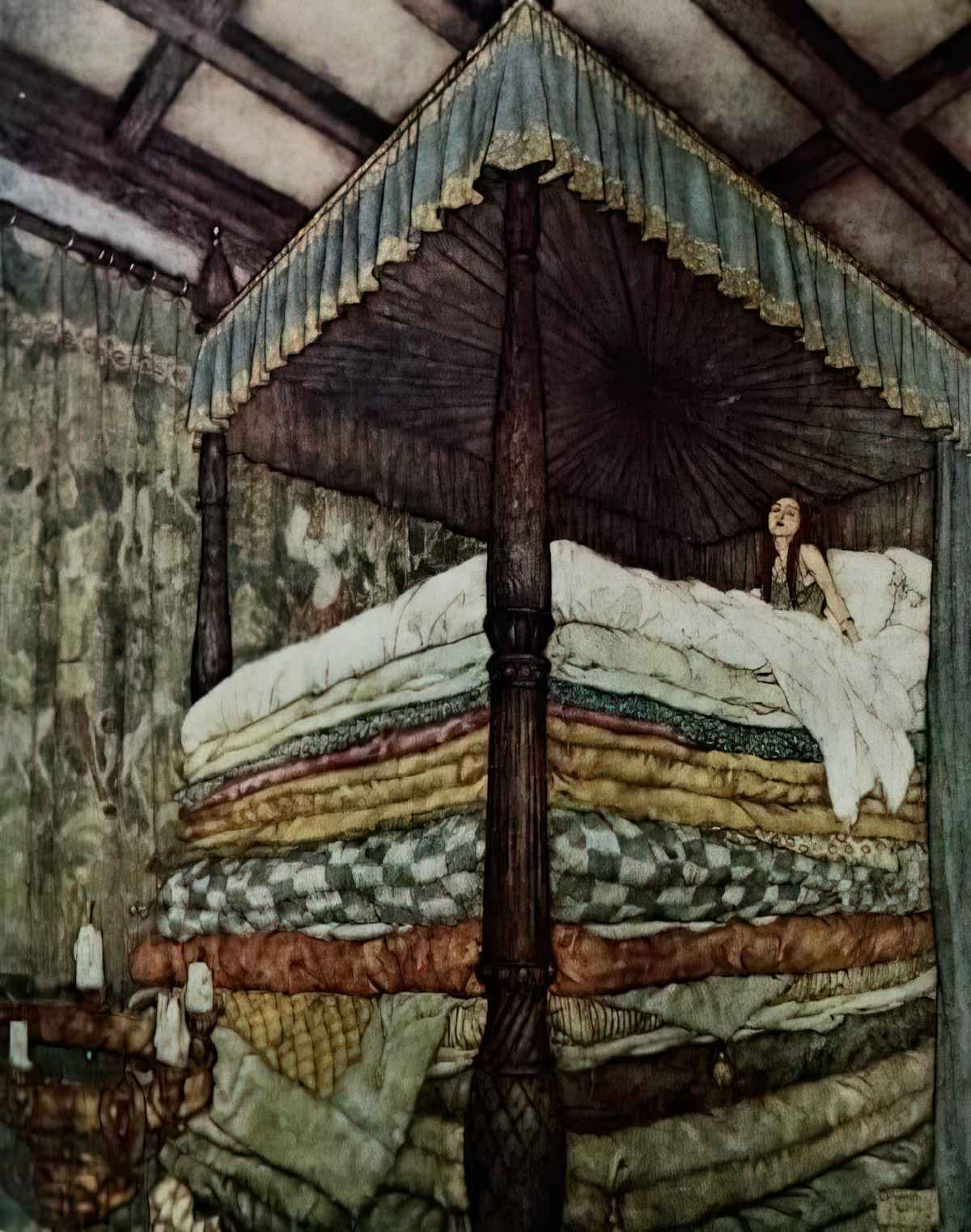

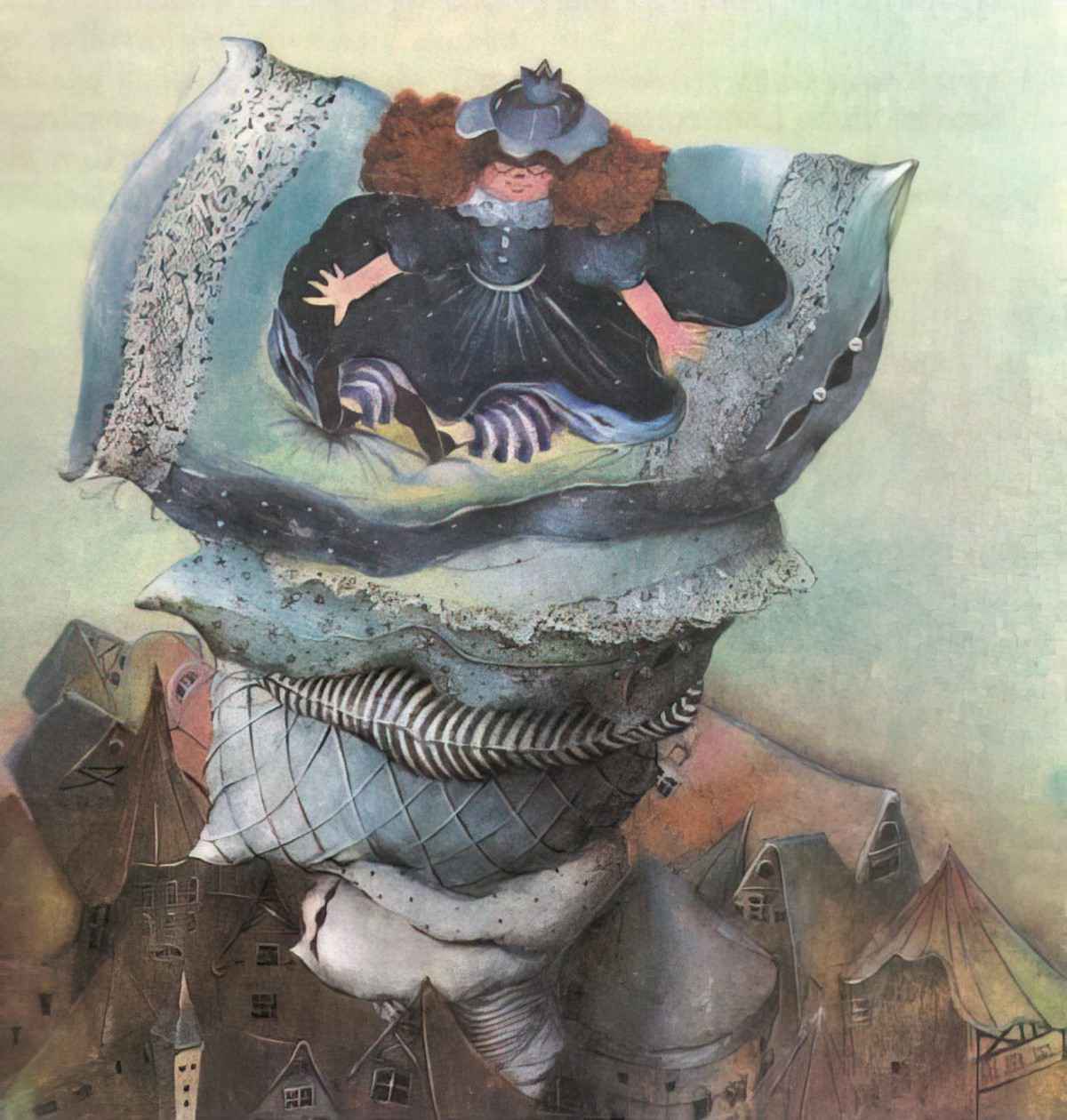

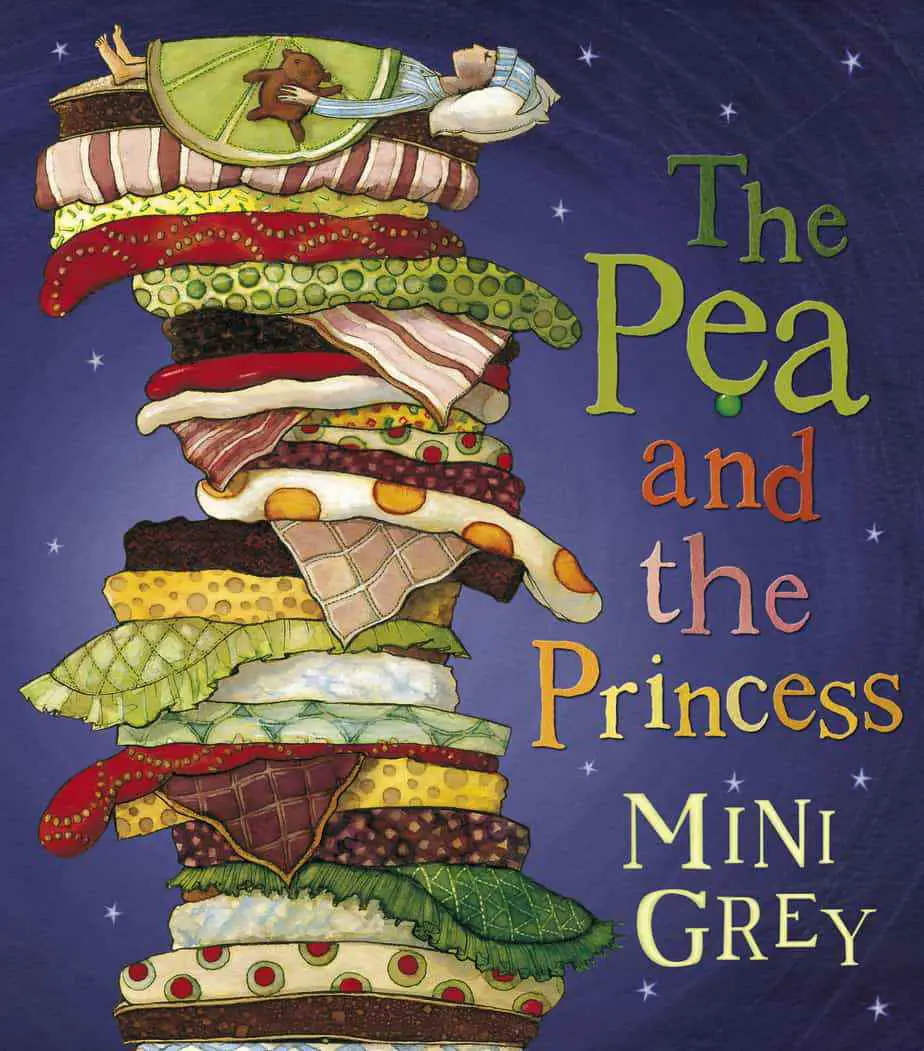

Every single retelling of The Princess and the Pea includes the iconic scene of the many mattresses, oftentimes on the cover. Like the glass slipper of Cinderella (which may derive from a mistranslation), the many mattresses in this tale are a resonant detail which helps this story to stay alive across generations. Images of hyperbole and excess stick in our memories. (Memory masters know this and use it.) Therefore, the more mattresses the better. Many illustrators even include ladders in the artwork.

One-point perspective doesn’t do a great job of conveying the height of the mattresses, but some illustrators go with that.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

American sit-com Seinfeld utilises a “Princess and the Pea” plot for “The Pen” episode in which Jerry takes Elaine to his parents’ house so they can go scuba diving. But the night before, Elaine tries to sleep on an uncomfortable sofa bed with no air-conditioning. When Elaine wakes up the next morning she’s in agony. Like the princess of Andersen’s version, she isn’t exactly quiet about it. Unlike in Andersen’s story, we see Elaine comically battle with the bed and bedcovers.

But the real struggle in the fairytale is the battle between the princess and the queen, who secretly tests the girl (much like a witch, actually).

Lauren Child understands that contemporary readers appreciate a more polite princess. Child might even be said to put some didacticism back in to a story which was never meant to teach:

At daybreak the queen knocked on the door with a cup of tea. “How did you sleep, my dear? I trust comfortably.”

Not wanting to be rude, the girl replied, “Oh, very well. Yes, perfectly. Thank you so much for asking.”

Despite trying not to be rude, Lauren Child’s princess is unable to keep up the ruse of polite civiity, and during a subsequent act of princess-like kindness, her soreness is revealed to the prince. This ending reminds me of my Raggedy Ann and Andy: A Thank you, Please and I Love You Book, which served to teach me basic manners when I was a toddler. Lauren Child’s princess serves as another polite role model. The lesson: we should not always say what we feel when we’re a guest in someone else’s house.

ANAGNORISIS

When the princess reveals that she had a poor night’s sleep, the prince (and his family) are convinced that she is respectable nobility, despite coming in from the forest.

All along, the reader has also been wondering if this girl is legit royalty. But what does it mean to be ‘royalty’? Is it a family thing or is it a vibe?

NEW SITUATION

Of course, Prince and Princess get married and live happily ever after. Now to Boner’s English language translation:

Boner has been accused of missing the satire of the tale by ending with the rhetorical question, “Now was not that a lady of exquisite feeling?” rather than Andersen’s joke of the pea being placed in the Royal Museum.

Wikipedia

This ending encourages a literal, surface reading, unlike Andersen’s ironic joke: Peas are the foodstuff of peasantry, yet here is a humble pea installed in a museum, just like this peasant girl is installed in the aristocracy. (Aren’t these royals just so kooky?)

Contemporary publications of “The Princess and the Pea” prefer Andersen’s pea-in-a-museum ending, realising that Boner’s alterations aren’t very good. Roald Dahl ended The BFG with a royal scene, elevating the supposed importance of one girl on an adventure. (I never liked this ending, but.) To end with an elevation (earlier in this fairytale it was literal, atop those towering mattresses) is to keep a story building and building, at least on an imagistic level.

WOULDN’T THE PEA GET SQUISHED ANYWAY?

The other weird thing Boner did with Andersen’s story: He changed one pea into three. Why? Because despite all the other ridiculous things in the text, he found it unbelievable that anyone, even a princess, would feel a pea beneath that many mattresses. So he solved it by adding another measly two? I wouldn’t feel three peas under my sheet, let alone under a mattress, let alone under 20.

Then again, when I think of peas, I think of green peas. Contemporary illustrations of peas have helped me to imagine that, because the peas in contemporary publications are painted for contemporary children, whose ‘peas’ are round and green.

Interestingly, when Japanese language borrowed the English word for peas, they kept the ‘green’, hence the contemporary Japanese word for green peas is ‘guriinpiisu’, グリーンピース. I always think it sounds more like Greenpeace. There’s also the native Japanese word for pea: mame, 豆. Japanese language does a better job of distinguishing between all the different peas, but then, they eat a much wider variety of vegetables than Westerners do.

Back to the fairytale: The peas Andersen had in his 1800s Danish diet were not green and squishy. They were yellow and hard, more like the dried legumes I sometimes drop into the crockpot for hearty winter soups. Andersen’s pea, uncooked, functioned more like a little pebble than the squishy green things I first imagined.

These hard peas, which needed long boiling before consumption, are the staple food item of “pease porridge” a.k.a. “pease pottage” from my childhood fairytale collections. The pease porridge rhyme is also a clapping game, and I suspect functions as comedic commentary on the awful monotony of a peasant diet, especially during times of famine. This diet varied only in temperature, not in substance.

Pease porridge hot

Pease porridge cold

Pease porridge in the pot

Nine days oldSome like it hot

Some like it cold

Some like it in the pot

Nine days old

On this week’s episode of A Taste of the Past, host Linda Pelaccio is joined by Clifford Wright and Tim McGreevy. In recognition of the UN’s International Year of Pulses, they discuss the history of pulses, from 10,000 years ago to their importance in today’s farming and diets.”Pulse” is a derivation from the Latin words puls or pultis meaning “thick soup.” Pulse crops are small but important members of the legume family, which contains over 1,800 different species.

Long History of a Little Pea

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

HAS ANDERSEN SUBVERTED ANYTHING IN THIS STORY?

In the end, this rich family has kept a hold of their power because they have admitted a ‘real’ princess into the family. She is real because she is princess-like, not because she was born into it. She arrives at the doorstep in statu nascendi; we know nothing about her. I deduce she’s a Puss In Boots character. Like Puss In Boots, she knows she’s worth it, so she simply rocks up at a castle and knows she’ll be admitted. (Puss In Boots is a cat, and needs a few tricks up his sleeve.)

Andersen didn’t write this story from scratch. He said he’d heard it as a kid. Fairytale experts have worked out he probably heard a Swedish version, related to a Persian and Arabic tale. In those earlier stories, the girl who rocks up in the night-time is not a princess in any sense, but a trickster who wishes to pass herself off as one. Personally, I don’t see much difference between the girl from the forest and the trickster girl who realises she won’t necessarily be taken at her word.

These earlier versions rely on the millennia-old idea that women are inherently liars and should not be trusted, especially when it comes to them securing a place in the marriage market. (A woman’s only chance at economic security.) Andersen doesn’t utilise that hoary old ‘women are liars’ trope here; the princess in his story really is a princess, by his reckoning.

The thing that makes this girl-from-the-forest a princess is not her bloodline but her princess-like sensitivity. (See: The Misplaced Importance of Bloodline In Fiction.) This was a radical idea at the time, and subverts the concept of ‘blue blood’, asking the reader to consider that ‘royalty’ is a personal characteristic and exists somewhere at every class. This is a concept contemporary readers will jibe with, and partly explains the tale’s longevity; we’ve seen Princess Diana’s sons marry commoners (okay, from the celebrity class). We see people rise from obscurity to fame, which suggests anyone has it in them to be rich and famous, given the appropriate merit.

That’s where we’re at today, but I’d like to see the concept of the meritocracy more widely challenged. A book by Daniel Markovits does just that. In The Meritocracy Trap Markovits argues that meritocracy produces radical inequality, stifles social mobility, and makes everyone — including the apparent winners — miserable, even though we take it for granted. Worse, these are not symptoms of systemic malfunction; they are the products of a system that is working exactly as it is supposed to.

Hear the author interviewed at Future Hindsight.

Do you find Andersen’s The Princess and the Pea a subversive tale? Have you found more subversive contemporary re-visionings?

THE PRINCESS AND THE PEA AS ALLEGORY FOR DISABILITY

Why is the princess able to feel the pea? Why is her skin so sensitive? At Once Upon a Blog, a post on illness and disability offers the idea that perhaps the princess has a skin condition which makes her especially sensitive to touch.

Tales that come most quickly to mind [when thinking of illness] are those like The Princess and the Pea, in which the princess bruises easily but also those other tales that feature skin marks and other unusual symptoms when the main character is affected by the elements (from the lightest touch of a petal – perhaps allergies, to moonlight – which could substitute easily for conditions brought on by the environment like asthma).

The Once Upon a Blog

When considering the sensitivity of the princess, I go to sensory processing disorder. This used to be a separate entry in the DSM but is now included under the banner of autism. (SPD, at time of writing, is considered a feature of ASD, common to everyone with any autism diagnosis.) If anyone could feel a hard yellow pea under their mattress(es) it would be someone with SPD, I reckon.

If looking for other classic tales about sensory processing disorders (allegorised or otherwise) there aren’t many to choose from but here are the stories related to The Princess and the Pea:

- Kathasaritsagara by Somadeva (11th century)

- “The Most Sensitive Woman” from Northern Italy

Here are all three stories on a single webpage for comparison.

RESONANCE

Partly because it’s so short, I think, this story remains popular as a picture book. (Picture books have been getting shorter and shorter, and now some of the most popular are 200-400 words.)

Also, princesses are evergreen characters, and can be used by feminist authors to convey new ideas about womanly ideals of the decade.

When it comes to sorting out a Real Princess from a Fake Princess, the famous pea-under-the-mattress test is tried-and-true. But for those of you who may have wondered how anyone could feel a tiny garden-variety pea under the weight of twenty mattresses, this book will put that question to rest once and for all.

This witty spoof was shortlisted for the prestigious Kate Greenaway Medal in the UK. It was Mini Grey’s first book and a worthy predecessor to such favorites as Traction Man is Here!