“Powers” is the final story in the Runaway collection by Alice Munro, published 2004. I find this story the most challenging of the lot — as in, what in holy heck was that all about? I’m going to have to write about “Powers” in order to understand it.

Here goes my best shot. What can we learn about storytelling from this novella? About life?

If this is not an easy story to read, nor was it an easy story to write. This from her editor:

On her own, Alice did eight revisions of “Powers”. Then we worked on that ending because it was hard to finish off the story part of it and give Nancy her due.

An Appreciation Of Alice Munro

The New York Times reviewer did not consider “Powers” a success:

“Powers” devolves into a melodramatic tale about a provincial Canadian woman, blessed or cursed with psychic abilities, and her exploitation by a charming but feckless man on the make.

NYT

‘Melodramatic’ is an unusual word to ascribe to Alice Munro — a decidedly realist writer. Why would they have said that? I put it to you that this story is melodramatic if read at a more literal level. My own interpretation is highly metaphorical, as in, I don’t think Ollie is a real person. I think he’s a creation of Nancy’s imagination.

Hear me out.

SETTING OF “POWERS”

TIME AND PLACE

Set in a small Ontario town after the First World War, the story spans about 50 years of Nancy’s life, starting as she’s about to get married, and skipping over the middle, child-rearing years.

FANTASY ELEMENTS

There’s a hint of fabulism in this one, which may partly explain accusations of melodrama. Except I don’t for one moment believe Tessa genuinely has clairvoyant powers — I read this as a metaphor for people who sit on the fringes of life in general.

When Nancy takes Ollie to see her clairvoyant friend they go through a tunnel. This tunnel feels like a fantasy portal. Even when the other side of a tunnel is in ‘the real world’ (rather than some high fantasy landscape), a tunnel within a story often indicates an other-world of some kind. Hayao Miyazaki loves a good tunnel. He uses tunnels in Spirited Away (reality > fantasy), in Ponyo (reality > magic tinged reality), and in My Neighbour Totoro (reality > magic tinged reality). Since one of the ‘rules’ of portals is that the characters must pass quite slowly through them, tunnels as portals tend to feature characters walking through them, on foot. (A car would be too fast.)

The world on the other side of this particular tunnel is perhaps leading to a heterotopia; perhaps it’s simply a separated place where the rules work differently, or where inhabitants are different and ostracised.

Perhaps this tunnel is, for Nancy, a portal into her own imagination? This is at the heart of my thesis.

Could we go even further? Does Tessa exist? Both Tessa and Ollie could be part of a paracosm Nancy creates for herself to cope with an un-companionable, aloof and vocationally-oriented marriage partner. After much thought, I think Tessa does exist, though with fantasy add-ons. Tessa is possibly a disabled person who Nancy imagines has superpowers. I think it’s just Ollie she’s made up as an alter ego.

ELEMENTS OF THE GOTHIC

When “Powers” turns to the psychiatric institution, Munro takes us into a gothic setting. This is where Munro starts to play with scale — ‘”Gothic” biomedical models rely on a metonymic process of substitution of the person for increasingly smaller cellular and ultra cellular units’ (Forgotten: Narratives of Age-Related Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease in Canada by Marlene Goldman).

In the dream sequence we’ll have a character dreaming of a character (mise en abyme effect) examining a pile of dead flies on a windowsill. It is noted that Nancy (subsumed by Tessa via a dream) doesn’t have a microscope, yet her eyes seem to zoom in on these iridescent fly wings. (She’s just met Ollie — perhaps imaginatively — and Ollie has trouble reading a menu. Equally old herself, it’s unlikely Nancy’s eyes would be capable of examining the detail of fly wings in real life.)

A CULTURE BUILT ON THE CONCEPT OF FEMALE HYSTERIA

Men, especially men of privilege, assume things will work out ok. As they always have.

They underestimate how easy it is for thing to go really poorly.

Just underestimating risk all over the place and pretending women are hysterical.

— Monjula Ray 🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️ (@queerBengali) January 3, 2021

When considering the setting of a story, we can’t ignore the major cultural forces which shape the characters. One dominant aspect of early 20th century misogyny involved the idea that women are prone to hysteria.

Freud’s “discovery” of hysteria was both anticipated by, and grounded in, 19th-century realist fiction. …the dark continent that Freud called femininity was brought to life by these realist novelists. The hysterical character, she argues, conceives of every relationship as tragic, imaginatively doomed — hence the warning which forms the title of this book. Yet this character speaks for everyone. The insights of Anna Karenina, Gwendolen Harleth, or Cassandra give to them a dignity beyond pathology or their social position. They are not merely literary “femmes fatales”. It is part of being civilized, the author argues, to fear the people and things we love, particularly when they are intimate to us. Knowing this, each person is responsible for the form this apprehension takes — whether awe or panic, respect or protest, desire or denial. […] Balzac, George Eliot, Charlotte Bronte, Tolstoy and Florence Nightingale […] are rich sources for understanding hysterical states of mind because they offer scope for interpretation that involves everyone as readers.

The blurb of Never Marry A Girl With A Dead Father: Women’s Troubled Relationships in Realist Novels

It is known that Balzac expressed his admiration for Dante. So when Munro’s character Nancy wants to delve into Dante, what is she really wanting? Insight into her own human condition? Wilf encourages against that, instead arranging a ‘useful’ life for her — one of choosing wallpapers and childbearing and mothering. This is exactly how misogyny works.

Patriarchy is what’s upheld.

Sexism is why it’s upheld.

Misogyny is how it’s upheld.

While reading “Powers”, look for the ways in which fiction is portrayed as fraudulent, i.e., fiction has the power to obscure the truth.

Back to my enduring hypothesis of Ollie as imaginary character: A character you invent yourself won’t necessarily tell their inventor the truth. Not immediately, anyway, though even invented characters can help their inventors discover something about themselves.

[“Powers”] explores … the ramifications of the increasing dominance of biomedical approaches to mental illness and ageing on Canadians from the perspective of patients and their caregivers. […] “Powers” repeatedly emphasizes the ethical limits of fictive consolation — by that I mean the consolation provided by fantasy and, by extension, literature.

Forgotten: Narratives of Age-Related Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease in Canada by Marlene Goldman

But an imaginary world can eventually reveal as well as obscure, because people use imaginary worlds in all kinds of different ways. In the end, Tessa’s conversation with Ollie (whether real or imagined) takes place on two different levels of her mind: There’s the story he tells her and the story she knows lies underneath. Nancy teeters on that interstial space between conscious fantasy and unconscious fantasy.

Of course, this story was written later than it is set. Is Munro writing of hysteria as if it’s a quirk of the past? No, she is not, and this is what makes her a feminist writer. That old ‘women are crazy’ chestnut is still influential today and can be seen in statistics as simple as how men are prescribed more pain killers, because when men say they’re in pain, men are more likely believed.

With Freud’s claims about the female psyche mostly discredited and the advances in treatment of mental illness over the years lauded, the average bystander might conclude that we’ve come a long way from labelling a normal reaction to sexual assault “hysteria.” But a long legacy of prescriptive and sexist science remains at the foundation of psychiatric medical treatment for women. From the first diagnosis of hysteria to the present-day disparities in mental health treatment, the tradition of medicating women’s emotions has held constant. Within this context, the line between empirical treatment and medicating the lived experiences of women grows dangerously thin.

Sophie Putka, The New Enquiry

Could Tessa’s clairvoyance be an analogue for hysteria? Or rather, not for hysteria itself, but how hysteria has been viewed by the medical establishment? Early in the story, Tessa’s clairvoyance is taken somewhat seriously. It is later shown to be part of her mental illness. Or is it? In Nancy’s dream at the end, Tessa might actually know telepathically what’s in Ollie’s pocket. Despite clairvoyance clearly not being a thing (within the world of the story), despite science debunking that whole thing, there’s always a lingering what if? Science from the past continues to influence the present, and has a very real impact on women’s lives.

Some critics consider this aspect one of the most interesting of “Powers” — Munro’s exploration of dementia and hysteria, united in the power they have over us as a culture — women used to fear hysteria; now more likely fear dementia:

Whereas Tessa’s mysterious powers of consolation lie in recuperating what has been lost, Ollie’s power seemingly lies in dissociating from his own vulnerability, and reducing women — most obviously Tessa — to scientific specimens. Ollie’s strategy recalls late nineteenth and early twentieth century biomedical approaches to both hysteria and dementia, which entailed locating the disease processes in women’s minds and bodies and using them as scientific material.

Forgotten: Narratives of Age-Related Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease in Canada by Marlene Goldman

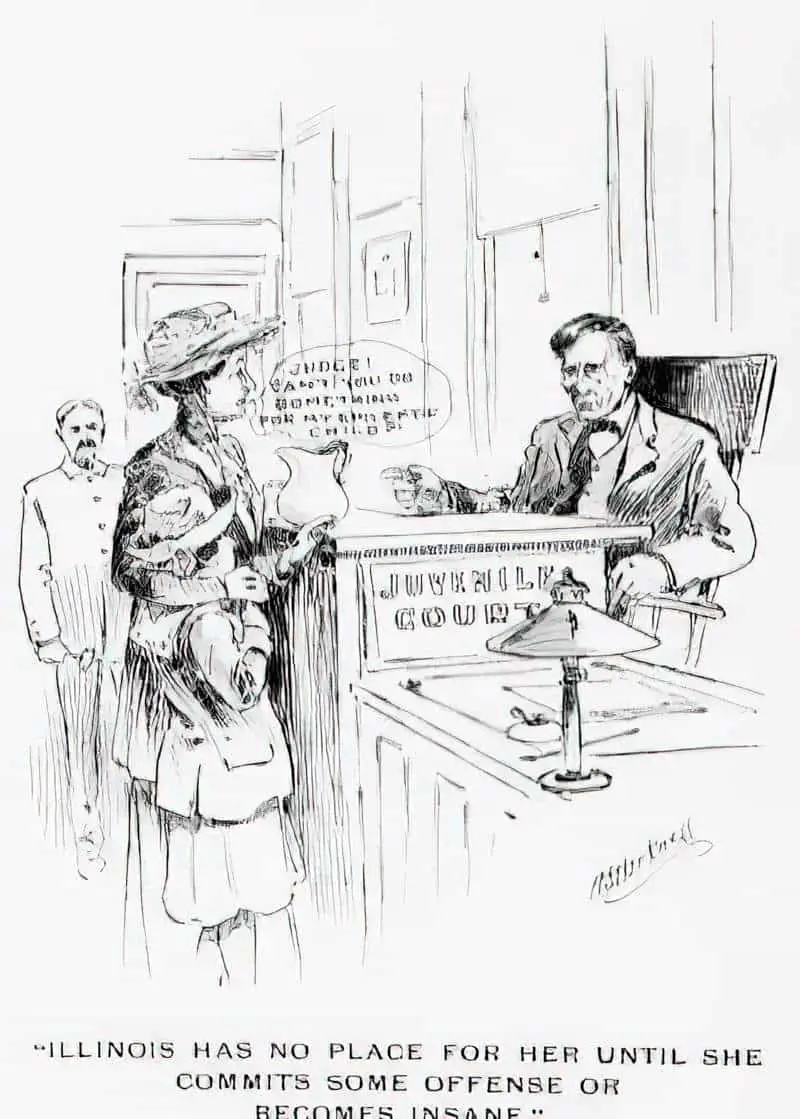

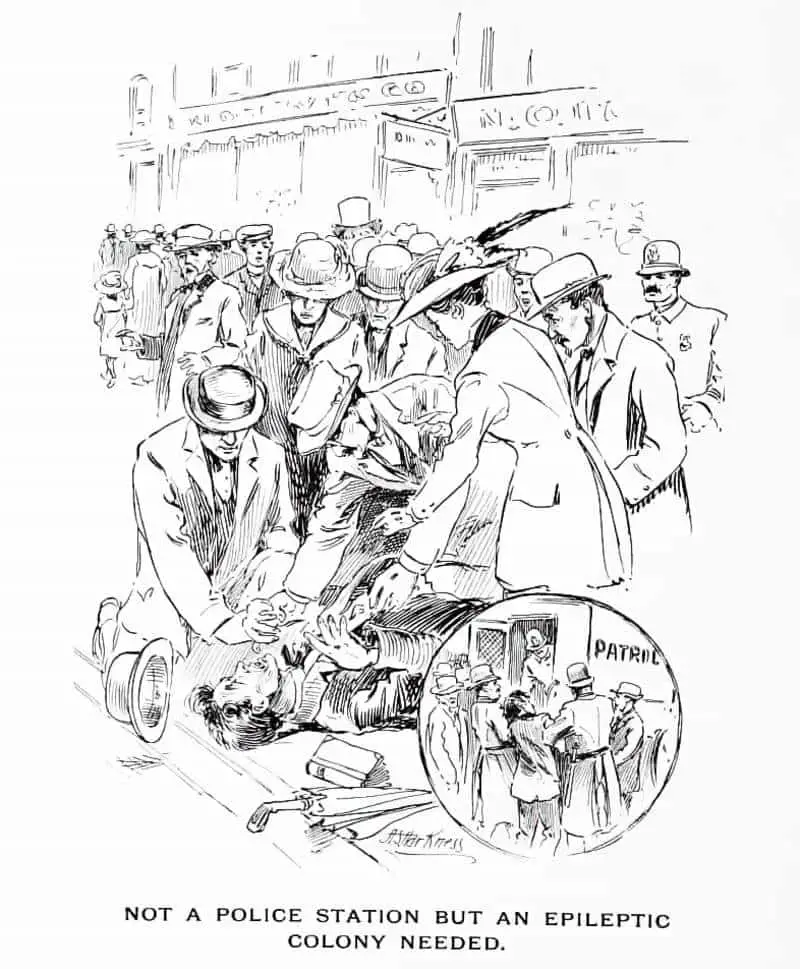

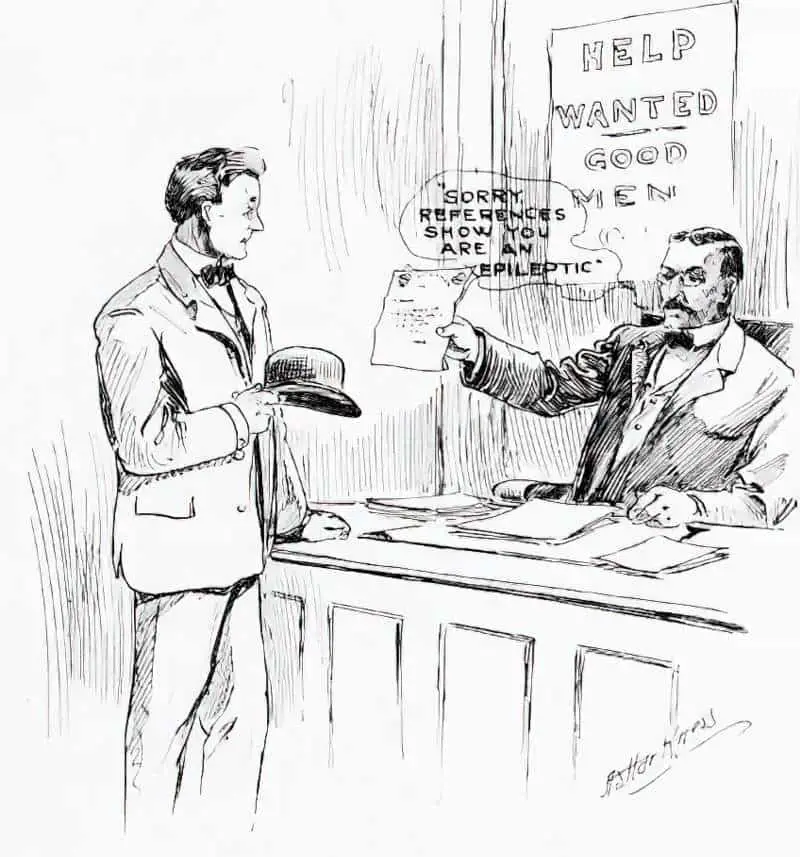

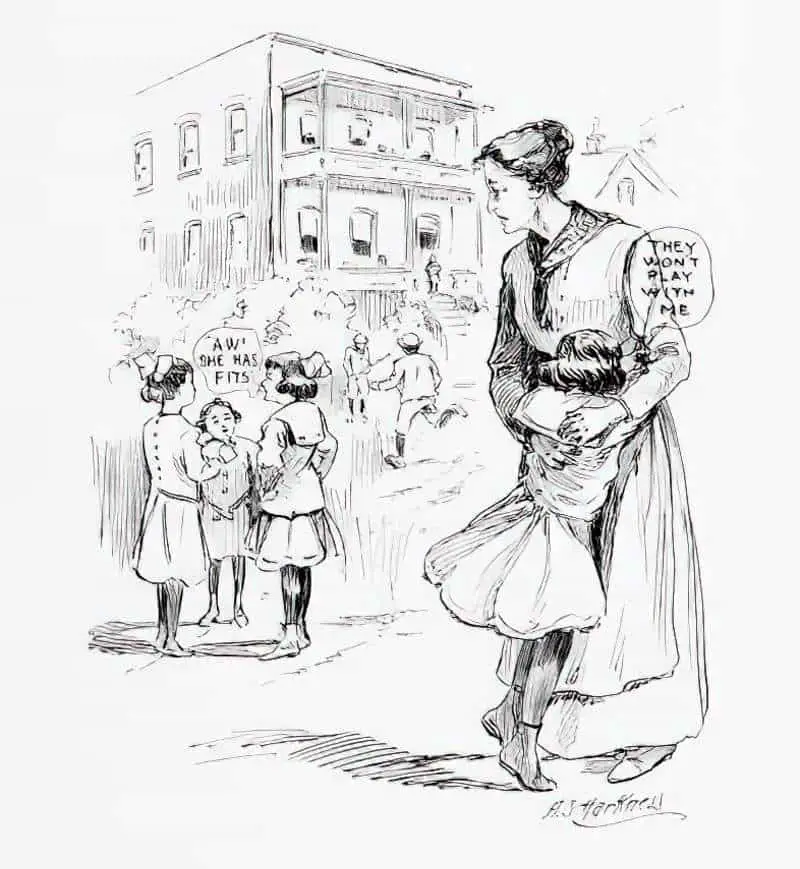

DISCRIMINATION AGAINST PEOPLE WHO HAVE ‘FITS’

After World War I, when the return of thousands of disabled servicemen forced disability onto the political agenda, disabled people were hidden from history, shut away behind the walls of asylums with their voices silenced.

Disability discrimination endures into today, though its exact nature morphs over time. Today epilepsy is much better understood. But in the early 20th century and prior, people who had fits were cast out as those with lepers were cast out. The following images offer some context:

When a disease is not well understood, people worry that it may be contagious or that it may be a moral problem, or possibly even a supernatural one. This story deals with the supernatural misunderstanding of fits.

CHARACTERS OF “POWERS”

Every life in this story is marked and decided by accidents and the unforeseen. Hence the clairvoyance thread.

Munro juxtaposes two women, the brisk, self-absorbed Nancy, and Tessa, a strange girl with extraordinary, fragile powers [MIRROR CHARACTERS]. Yet it is Nancy, the skeptic and rationalist, who succeeds in peeling back the obscuring film over the past. She protests that she doesn’t want to live the past – she only wants to “open it up and get one good look.” That glimpse has such a weight of truth that though it may be dream or imagination, it is real and meaningful – like Munro’s own work.

Quill and Quire

Nancy

At the beginning of “Powers” she has just finished high school. Nancy’s diary entries portray her as capricious and full of life — her youth and lack of maturity shine through. I’m reminded of Kelly Kapoor from the American version of The Office, whose focus on weddings is all-consuming — she hasn’t thought about what it will be like to be married.

But Nancy has more empathy for others than Kelly, who is utterly self-absorbed. By Nancy’s own admission, she marries Wilf because he has already been turned down, and she doesn’t want to embarrass either of them by saying no.

Nancy has been brought up in a culture in which a woman’s needs are subsumed by that of a man — she makes it a goal to find out more of Wilf’s interests so that they’ll have something to talk about. (At no point does she expect him to be interested in her — and he is not.) She becomes pregnant soon into their marriage and we learn later she has had multiple children. These children are not mentioned — the early childhood years are skipped over.

Much later, with childcare done and dusted, she is now caring for her husband with dementia. Now Nancy is asked by the psychiatric institution if she would also care for Tessa. The emotional burden heaped upon women is a thread across the stories of Alice Munro. Take for example “Deep Holes”. There is a scene early on in which the reader is made fully aware of the effort that has gone into preparing a picnic to suit the individualised tastes of each family member. These efforts go unrewarded. Her ungrateful son cuts ties with her after he grows up, and as an older woman, the main character must find a way to live with this ingratitude.

Nancy visits Tessa in the psychiatric institution. Facing a painful moral dilemma, Nancy must decide if she has it in her to care for the both of them. Don’t forget, she’s been taking care of other people her whole adult life.

The moral dilemmas throughout “Powers” revolve around balancing Nancy’s own needs against caring ‘responsibilities’ the culture has instilled in her. A lot of woman readers in particular will identify with this.

Older Nancy has undergone a character arc in the parts left out of the story. She doesn’t have the spoons to care for anyone else. She leaves Tessa at the institution and returns to her own home.

To this end, I think Ollie is an imaginary invention to help Nancy assuage her own conscience. When you’ve been brought up to put the needs of others before your own, and then you suddenly can’t, or don’t, you need to find a way to justify your own actions to yourself. Imaginary Ollie helps her with that.

Of course, none of this would explain how Tessa ended up in America. I don’t think it matters which parts of the story occur within the ‘real world’ of the story and which occur in the ‘imagined world’ of the story. It’s all highly mutable. The whole story exists is a dream space, after all.

Wilf

Wilf is the thirty-year-old town doctor, who asks much younger Nancy to marry him. He’s just asked someone else and been turned down. He is portrayed as a very distant, self-contained character.

Unlike in “Tricks”, the previous story of this collection, the reader has no sense that Nancy and Wilf will be a good match. There is no “I understand you” moment” (as Matt Bird calls it).

Alice Munro has said in an interview that marriage was different when she was young — young people of marriage age just sort of picked someone and went along with it. In contrast, dating today is a game of enormous choice, made all the more confusing by the illusion of online choice, and it would now appear foolish to ‘settle’ on someone without going through an extended period of dating many partners first. Nancy and Wilf both belong to this older generation who expect different things from marriage (not friendship, for instance) and who would like to get married so they can get on properly with their adult lives.

Wilf seems to want a uterus more than he wants a partner — he tells Nancy to ‘give Dante a rest’. He doesn’t want someone who is a deep thinker or an equal in conversation. He doesn’t respect that Nancy may really enjoy more difficult things. And he knows he can mould Nancy into whatever he wants her to be. The era makes this easy — an era in which wives did as their husbands instructed. They had no other real choice.

Towards the end of “Powers” we learn that Wilf lives with dementia later in life. Nancy has faithfully served as his wife and caregiver.

Ollie

As noted above, Ollie may be Nancy’s invented, male alter ego.

Ollie is supposedly Wilf’s younger cousin, Nancy’s own age (by no coincidence).

Ollie starts out wanting to be a science journalist. Perhaps if Nancy were a man that’s what she’d like to do. Her interest in Dante suggests a youthful interest in deeper things than wallpaper and mothering.

Ollie is mercenary and capitalist. He could be the human embodiment of all that is wrong with modernisation (“getting and spending”). When he thinks Tessa has psychic powers he marries her in order to exploit her for money. He runs off to America with Tessa but sticks her in a dodgy institution which is not approved by the authorities.

Why does Ollie treat Tessa the way he does? Shouldn’t he know what it’s like to be so vulnerable? Well, that’s not how lateral violence works.

Pain that is not transformed is transferred.

Fr. Richard Rohr

Readers learn that prior to visiting with Wilf and Nancy, Ollie spent three years in a TB sanatorium. As a patient he was subject to protracted, invasive treatments. Wilf, who is portrayed as an extremely dispassionate and detached physician, explains that doctors collapsed one of Ollie’s lungs so that they could treat the infection. While Wilf calmly recounts Ollies’ treatment, the latter puts his hands over his ears. As Ollie confesses, he prefers not to think about what was done to him. Instead, as he admits to Nancy, he “pretends to himself he is hollow like a celluloid doll”. Ollie’s experience as a TB patient is relevant for several reasons. First, it recalls Sontag’s discussion of the dread that attended TB — a dread that currently haunts Alzheimer’s disease. Second, Ollie’s traumatic experience may have motivated him to pass on this sense of dread. Ollie’s response is significant because it offers insight into the predicament of the elegist, who, confronted with the death of the other, recognizes his own vulnerability and mortality. In the masculine elegy, the poet responds by deifying the deceased and, at the same time, celebrating his own survival. […] Ollie’s treatment of Tessa echoes this patterns.

Forgotten: Narratives of Age-Related Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease in Canada by Marlene Goldman

I find Ollie and his backstory unlikely, which is why I consider him a character inside Nancy’s imagination. Conversations she puts down to Ollie could easily be conversations she has with herself, or when other characters seem involved, what Ollie says could easily be what Nancy says, or what she would like to say.

Naturally, we can read any literary character in this way. Here’s the list of reasons why I suggest this guy be coded as Nancy’s creation:

- Nancy’s diary demonstrates she wants more from life than she gets, and inventing a parallel, peopled life would be one way of getting that.

- Ollie might be an invention to assuage Nancy’s own guilt — guilt that she doesn’t have it in her to care for both her own husband, own children as well as her childhood friend who winds up in a horrible institution. She can imagine she’s cared for by Ollie.

- Ollie may also be an invention to help Nancy cope with loneliness within marriage.

- Ollie’s hinted-at bisexuality may be more of a gender fluidity, in which Ollie is partly made up of Nancy, partly made up of Wilf (she’s made him Wilf’s cousin, after all). What she doesn’t get from Wilf (companionship and conversation) she is getting from Ollie, more or less. That said, Ollie doesn’t exactly tell her the truth. Why not invent a fictional character who at least tells you the truth? Because you may not even know the truth yourself. You can’t have an imaginary character tell you the truth until you’ve wrestled with the real situation yourself.

- Imaginary worlds come and go throughout a person’s life — busy with young children, it would seem natural Nancy had no time to even conjure Ollie for all those years, explaining the time jump. It’s at the ends of her life that she has the space to invent, and think, and overthink, and blame herself, and to try and make amends.

- Wilf clearly knows little about his own cousin. I accept that he’s an inward looking man, but still.

- Ollie ends up on Texada island. Islands are highly symbolic other spaces — especially in other Alice Munro stories. For example in “Cortes Island” the island is an imaginary space for main characters — imagined as a way of coping with day-to-day life.

- Ollie took Tessa around the vaudeville circuit. The vaudeville world itself is another fictional arena — perhaps a fictional world within a fictional world. It’s not exactly a run-of-the-mill way to live a life — more likely to occur in fiction than in reality.

Vaudeville and the Making of Modern Entertainment, 1890-1925

Vaudeville is one of the most famous styles of theater in American history, a font of showbiz legend and the training ground for a generation of stars. It’s also one of the least studied. In his new book, Vaudeville and the Making of Modern Entertainment, 1890-1925 (UNC Press, 2020), Professor David Monod examines Vaudeville as both a cultural form and a for-profit industry, connecting the two to produce a remarkably cohesive portrait of a vast phenomenon. The genre, he argues, was related to a distinctly American form of modernity, offering its vast audiences an enjoyable respite from the pace of modern life—and a way to express and understand the world-shaking experiences of their era.

New Books Network

Tessa

The reader is not afforded a look into Tessa’s mind, except perhaps at the end as Nancy’s dream lets her look through Tessa’s eyes.

Tessa is Nancy’s childhood friend. She dropped out of school when she was 14 due to an unnamed illness, later revealed to include seizures. She is small in stature, as if illness has caused lack of growth.

Nancy cryptically explains to the reader that Tessa is “not in the world that the rest of us are in”. (This may give them something in common, if Nancy has this really rich imaginative life.)

We are eventually told that Tessa is a clairvoyant. Tessa uses these so-called psychic powers to help the townspeople find hidden or mislaid objects, sometimes even dead bodies.

Vulnerable, childlike Tessa marries Ollie, who has written an article about her, sending many people to her house. (This minor celebrity creates some havoc.) As Nancy has passively accepted her own entry into wife- and motherhood, Tessa seems to passively accept all this, and goes along with Ollie who transplants her to America.

But Ollie is a man and his caregiving capacities are limited. He puts her in an institution, which eventually closes in the late 1960s.

Like Wilf, Tessa also suffers memory loss as an older person. Dementia may combine with mental limitations caused by a lifetime of seizures — the difference is unclear and unimportant to the story.

NARRATION OF “POWERS”

The Guardian’s view of Nancy is less kind than my own:

“Powers”… is a little masterpiece of impersonation, an uncanny inhabiting of the mind of a meddling, egotistical girl and of a distinct historical period. The long range of Munro’s stories is only made possible by her apparently effortless possession of decade beyond decade of the past, her technique being the opposite of so much information-bolstered fiction of the present: she knows that life in the past was unhampered by any sense of its future quaintness, so she doesn’t explain. She gives us a past as unselfconscious as today. […] The sweep of the thing, the unfolding picture of the unforeseen life, the interlocking strangeness and ordinariness, the unravelling narrative of Nancy’s own consciousness, together make a deep impression.

The Guardian review

STORY STRUCTURE OF “POWERS”

“Powers” is divided into five parts each with chapter names:

Give Dante a Rest

TIME: Spring, 1927

NARRATION: first person diaries of an unnamed character

Nancy, fresh out of high school, is convinced that she is destined to live a life of importance.

She has a joking, trickster side. She startles the town doctor, Wilf, on April Fool’s Day by rocking up at his house pretending to have a sore throat.

He does not share her sense of humour at all and tells her to get out. (He’s probably a good 12 years older than she is, which would be intimidating. This scene is the inverse of an “I understand you” moment. The reader can see that these two are wrong for each other.

Rather than blaming the doctor for his lack of humour, she feels really stupid. She was only having some fun, and perhaps trying to get his attention. The difference in maturity (borne of age difference) is also a factor here.

She sends a note of apology and hears nothing back, but when she’s trying to get through a novel by Dante, the doc turns up at her door, takes her out to see some ice breaking, and completely out of the blue offers his hand in marriage.

Nancy accepts his proposal, not because she feels affection for him, but because she can’t think of a good reason to say no — she doesn’t want him to feel bad, because her friend has already turned him down.

In her diary she seems disappointed that her life has turned out so mundane after all. Like all the other eligible young women she knows, she’s going to get married. (And she’s about to marry a doctor — financial stability for life.) Her path is set now. She’ll have his babies. He assumes so, too. She’s not going to have the special life she dreamed of.

This reminds me of Angela Hayes from the film American Beauty. Angela’s biggest fear is to be ordinary.

One of the worst criticisms that can be levelled at a young woman: “She thinks she’s all that.” She has ideas about herself.

In fiction, young women with aspirations above their station will invariably have rich imaginative lives. Of course they do, right? These characters have the ability to imagine how their lives might be, and that in itself requires imaginative power.

[NANCY’S PSYCHOLOGICAL WEAKNESS] Imagination itself can be a liability when you start to recast yourself. Safer, indeed, to invent a paracosm with a wholly original cast. Keep yourself right out of it, stories tell us, time and time again. In American Beauty, Angela’s story about herself (as a sexually experienced ingenue) seeps into the real world, making the actually virginal Angela highly vulnerable in the presence of her best friend’s sexual predator father.

Alice Munro doesn’t let us in on the exact nature of Nancy’s fantasies about herself. Or does she? (Cue the invention of Ollie. Perhaps she wants to be a science journalist, freed of the burden of caring for others, living on an island.)

Girl in a Middy

TIME: several months after Give Dante A Rest

NARRATION: third person

Nancy and Wilf are engaged and preparing for their wedding. Wilf’s cousin Ollie is in town to attend the ceremony. Nancy becomes fascinated by his worldly affectations.

In an attempt to impress him, she takes Ollie to visit Tessa, Tessa correctly identifies all of the items in Ollie’s pockets. Ollie seems to dismiss her, but Nancy fears he has ulterior motives.

Nancy writes to Tessa, warning her to avoid Ollie. Tessa responds, revealing that she and Ollie have already eloped to the United States. They intend to get married and test her abilities scientifically. Tessa ignores Nancy’s cruel but shrewd injunctions that Ollie only wants to exploit her gift for commercial ends.

Here’s a feature seen across Alice Munro’s short stories: There is a revelation, we expect the story can close now, but no — Munro is just cranking up. Each of these sections contains its own mini anagnorisis.

One might have thought the climax of the story occurred with the revelation that a couple had run away together at the end of “Girl in a Middy”. It is certainly a surprise, though one ushered in with little pomp, right at the end of the segment.

But if one identifies the climax of the story as falling in the third “act”, one must choose a moment other than this one, something in “A Hole in the Head”. (Well, that seems like an obvious moment, doesn’t it, but in fact that hole already existed, or never existed, or still exists. In typical Munro-fashion, each of these scenarios seems possible.)

Perhaps the moment in which one woman realizes that the other is operating under the assumption that her lover is dead, the moment at which she chooses not to correct the misunderstanding, the moment at which she turns her back on her and leaves her there, isolated and confined.

Buried In Print

A Hole in the Head

TIME: forward into the 1960s

NARRATION:

Nancy is now an ageing woman visiting an American mental hospital. Along with many such facilities of this era, the ward is shutting down. Nancy has received a letter asking that she retrieve Tessa, who has lived there for some time.

When Nancy and Tessa meet, Nancy tries to learn about Ollie and his life with Tessa. Tessa, however, cannot remember anything. Perhaps electroshock therapy has ruined her memory. Tessa claims that someone may have strangled Ollie, but recalls nothing else. Tessa then guesses that Nancy plans to abandon her at the facility. This is true. Feeling guilty, Nancy promises to write her letters. She never does.

A Square, A Circle, A Star

TIME: moves forward a few more years.

NARRATION:

Wilf has died from the complications of a stroke (suggesting he had vascular dementia). It’s only now that Wilf is dead that Nancy has the spoons to consider her obligations to Tessa.

Nancy’s friends have filled in where Wilf left off, urging her against getting too invested in her own demons. They tell her to get out and about, to get involved in social activities. As she has done her whole life, despite seeming capricious in her diary entries, Nancy does as she’s told. She goes on a ghastly geriatric cruise at their behest. But now it seems she’s done with people telling her not to go deep into her own mind. Though this part is summarised rather than shown, her experience on the cruise ship seems to have switched something over in Nancy — she will no longer fill up the rest of her life with frivolities that keep her entertained on the surface.

So she visits Vancouver. What a coincidence. She bumps into Ollie. (Not a coincidence at all if you’re with me here and Ollie isn’t real.)

She and Ollie go to a Japanese restaurant, then to a coffee shop, where they continue their long discussion. Ollie discusses his travels with Tessa in the United States. He says that funding for research disappeared after World War II, forcing he and Tessa to work on the vaudeville circuit.

Vaudeville a type of entertainment popular chiefly in the USA in the early 20th century, featuring a mixture of speciality acts such as burlesque comedy and song and dance.

The only way to make any money that they discovered was to go with the travelling shows, to operate in town halls or at fall fairs. They shared the stage with the hypnotists and snake ladies and dirty monologuists and strippers in feathers.

Focusing on the burlesque aspect, I see older Nancy as a burlesque witch. (Better to click through on that to know what I mean.) The modern burlesque witch tends to view herself as a younger woman trapped in an old woman’s body. The following passage demonstrates this exact experience in “Powers”:

It happens only a few times in your life—at least it’s only a few times if you’re a woman—that you come upon yourself like this, with no preparation. It was a bad as those dreams in which she might find herself walking down the street in her night-gown, or nonchalantly wearing only the top of her pajamas [FEAR OF DEMENTIA OR ACCUSATIONS OF HYSTERIA].

During the past ten or fifteen years she had certainly taken time out to observe her own face in a harsh light so that she could better see what makeup could do, or decide whether the time had definitely come to start coloring her hair. But she had never had a jolt like this, a moment during which she saw not just some old and new trouble spots, or some decline that could not be ignored any longer, but a complete stranger [SHE HAS HAD A MAJOR ANAGNORISIS, OR REVERSAL].

Somebody she didn’t know and wouldn’t want to know.

The strain of performing gave Tessa headaches and gradually eroded her powers, but they developed a system to deceive their audiences. (Much as Nancy has ‘developed a system’ to deceive herself — the invention of Ollie.)

Eventually, Ollie tells her, Tessa died. Nancy does not contradict him but feels all through the conversation that he has not been telling the truth. Ollie drives her back to her hotel, and she is about to invite him to spend the night in the other bed of her motel room. This is because he appears to have nowhere to stay but inside his jalopy. Before she speaks, however, Ollie turns her down, as if he possesses a less magical form of clairvoyance himself. Or perhaps there’s no clairvoyance, so much as Ollie being literally of Nancy’s own mind.

Nancy feels complicit in Ollie’s lies to the point where she feels she is lying herself in not protesting at it. (If Ollie is an invented character than she is indeed lying to herself, via Ollie.)

To make things right, Nancy decides to find Tessa and bring her to Ollie. However, she does not succeed.

Flies on A Windowsill

TIME: decades later

NARRATION:

Nancy’s grown children have been kept off the page, but now we learn they worry that Nancy is living in the past. In other words, they worry she’s living inside her imagination, not in the real, current world. (I suspect ‘living in the past’ is an accusation levelled at older people, whereas a young person would be accused of living ‘inside her head’.)

The story closes with a dream. Nancy falls asleep and dreams about Tessa and Ollie. They are staying at a motel. Tessa suffers from a terrible headache. In the dream, Tessa sees a messy little pyramid of flies hidden on the sill behind the curtain. Excited that her psychic powers have returned, she awakens Ollie and they embrace. As they embrace Ollie worries that Tessa can sense the papers in his front pocket, which will commit her to a mental hospital. It is implied that Tessa does indeed sense the paper’s presence. But she no longer cares what happens to her. Nancy then dreams that Ollie decides to spare Tessa. As she does so, a feeling of reprieve lights up her dream. Nancy is pulled out of it as her consciousness disintegrates around her.

It is a bold choice to end a story with a dream sequence. Do you consider this a successful short story? What did you get out of it?

Header photo by Hoshino Ai