Before taking a look at postmodern picture books, let’s take a look at how the postmodern short story has been described.

THE POSTMODERN SHORT STORY

The postmodern short story came in the middle of the 20th century. Stories became ‘anti-stories’. Postmodernism is “art’s way of replenishing itself by way of returning to the past in general, and to itself in particular”.

- Postmodern plots don’t have cause and effect relationships. One word to describe such plots is ‘disjunctive’ (lacking connection between parts).

- What do disjunctive plots look like? They might be palimpsestic, collage-like, almost certainly non-linear.

- “Reality” appears in quotation marks. There’s no such thing as “reality”.

- Metafiction is commonly utilised.

- Characters are flattened.

- Symbols convolute upon themselves.

- Postmodern work is intertextual and allusive (“Immature poets imitate, mature poets steal” – T.S. Eliot) Stories might be a pastiche (an overt re-visioning of something that has come before).

- Postmodern work takes a synchronic approach to time (Synchronic: Concerned with something as it exists at one point in time.)

- There’s a tendency to deconstruct binary oppositions.

- Postmodern works are often playful, parodic and self-reflexive.

- They question authenticity. (Artifice is foregrounded.)

- Postmodern work is inherently creatively artistic

- Postmodern work encourages interest in the past.

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined in studio by astrophysicist Dr. Adam Becker to talk about his new book, “What is Real? The Unfinished Quest for the Meaning of Quantum Physics.” They talk about the important role philosophy plays in understanding the scientific process as well as what happens when you question one of the sacred cows of quantum physics, the Copenhagen interpretation.

What is Real w/ Adam Becker

While children’s literature is generally considered less rigorous and interesting than literature for adults, this is not the case. Postmodern picture books require work on the part of the reader before they make full sense.

Different cultures expect different interactions with story. It’s possible Western audiences are expected to do less work in contributing to a story.

I’m reminded of an observation a friend of mine made when he lived in Japan for a while, about the difference in audience reactions to narrative twists and storytelling expectations, and how that shapes the way stories are told.

“In America,” he said, “Audience will see a movie and say ‘That made no sense, what a dumb movie’. In Japan, they tend to say, ‘That made no sense, so I need to see it again so I can understand it better.” I don’t know if the cultural observation is accurate, but…

@marshallmaresca

A key concept when discussing Postmodern works: Postmodernism describes how the audience interacts with a work. A Postmodern work is not inherently Postmodern, though we can’t cop out there. Certain works do lend themselves towards a Postmodern relationship with audiences.

EXAMPLES OF POSTMODERN PICTUREBOOK WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS

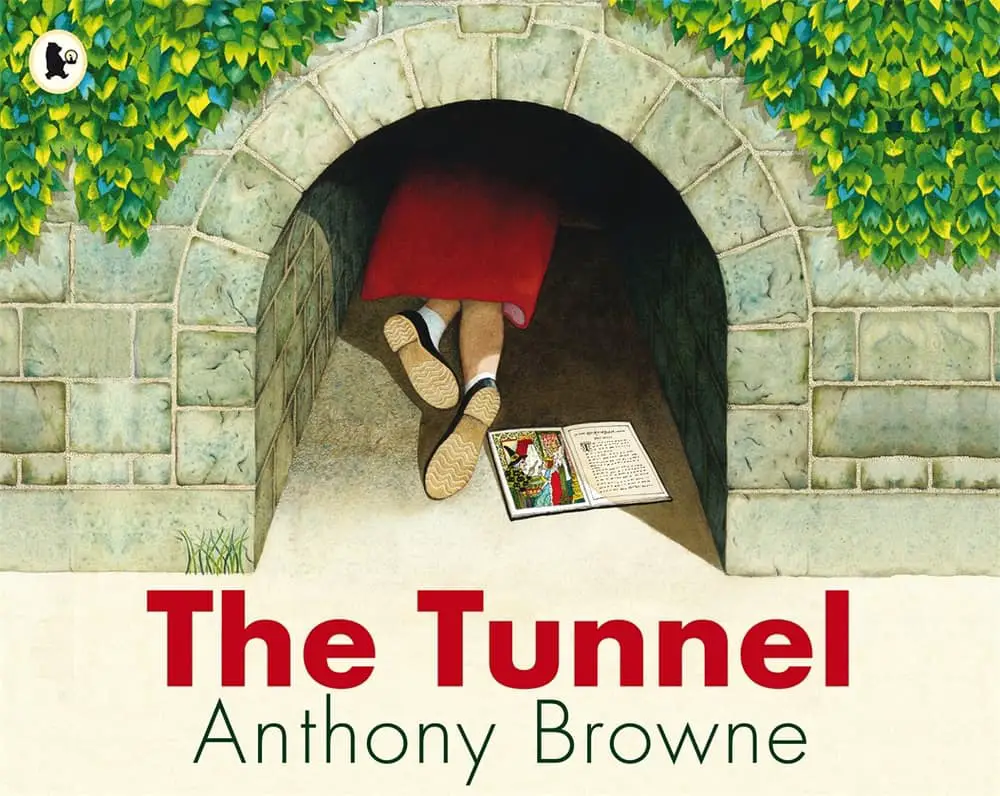

- Anthony Browne – very much at the forefront of the postmodern picturebook

- Shaun Tan — Australia’s own standout example

- Chris Van Allsburg — American

- David Wiesner

- Jon Scieszka [his website tells you how to pronounce his name] – strong humour – most books which use this style do so as a joke.

I have no doubt that the word Postmodern annoyed people when it first appeared.

The Gendered Nature Of What We Call “Postmodern”

I note with interest that all of these tentpole postmodern picturebook creators happen to be men. Are we publishing and then talking about women who create postmodern picturebooks?

Let’s not forget the wonderful postmodern work made by non-men e.g.

- The Whisper by Pamela Zagarenski is similar to Anthony Browne’s Into The Forest in many ways. It operates on two diegetic levels (which makes it meta), a girl enters a Surreal dream space full of collage-like illustrations full of fairytale allusions. These allusions encourage readers to flesh out the imaginative part of the story themselves. At the end, the veridical world of the story and the imaginative world remain intertwined, which is in line with the Postmodern idea that nothing is certain.

- Reflections by Ann Jonas encourages readers to examine pictures by using the same trick as Anthony Browne — things in the trees. The story happens within a ‘reflection’ of the real world, which definitely defamiliarizes — another Postmodern trick. The reader is even required to turn the book itself around, which reminds the reader they are reading an object and is therefore meta. It operates like one of those optical illusions in which the same image can look like two people in profile or like a vase, depending on who is viewing it and when.

The following books are created or partially created by non-men. Do they fit into existing definitions as Postmodern?

- There Is No Dragon In This Story by Lou Carter

- Our Little Inventor by Sher Rill Ng

- Books by Jeannie Baker e.g. Mirror

- Books by Baek Heena

- Tove Jansson’s Moomin books??

- The Great Realisation illustrated by Nomoco

- The Three Bears Sort Of by Yvonne Morrison

- Here and Now by Julia Denos

- Z Is For Moose by Kelly Bingham

- There Are Cats In This Book by Viviane Schwarz

- Wolves by Emily Gravett

- The Red Book by Barbara Lehman

- Snappsy The Alligator (Did Not Ask To Be In This Book) by Julie Falatko

- The Whisper by Pamela Zagarenski

- The Book Chook by Amelia McInerney

- Wolfie the Unlikely Hero by Deborah Abela

- Not a Stick by Antoinette Portis

- Woolvs in the Sitee by Margaret Wild

- Are commentators unwittingly failing to see standout Postmodern picturebooks created by women?

- Are covers with women on the title deemed subconsciously less interesting? I really hope not.

- Is a more feminine style of humour being edited out of very funny books before reaching the reader?

- Are publishers more willing to gamble on novel and not-seen-before books from men, either subconsciously or consciously? Postmodern books are often aimed at older picture book readers, and unless they achieve cult status in schools, are therefore more difficult to market.

I don’t know. But these are all very interesting questions. There is a widely held misconception that girls do as they are told whereas boys push boundaries. I’ve heard friends say this with certainty, based on observation of the children in their lives. It’s quite possible this same cognitive bias (we see what we expect to see) applies to literature. Postmodern works are inherently boundary-pushing.

References

- B.P. Goldstone (1999). Brave new worlds: The changing image of the picture book. The New Advocate, 12, 331-344.

- S. Pantaleo (2002) Grade 1 students meet David Wiesner’s three pigs, Journal of Children’s Literature, 29, 66-67.

- Articles from Papers journal about postmodernism.

- Jane Doonan, The Lion and the Unicorn (I think this link?)

- Crossing The Boundaries (2002) by Michaelle Ansty and Geoff Bull. Several chapters are about postmodernism.

Postmodernism and America

In a 2012 article called “Rooting Interest”, American author Jonathan Franzen described the existence of at least four “genealogies” of American fiction:

- Henry James and the modernists

- Mark Twain and the vernacularists

- Herman Melville and the postmoderns

- “there is a less noticed line connecting William Dean Howells to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sinclair Lewis and thence to Jay McInerney and Jane Smiley, and that [Edith] Wharton is the vital link in it.”

Interaction Between Reader and Storyteller

Postmodernism doesn’t describe a work of art so much as a way of looking at a work of art. When you first read a postmodern picturebook, chances are you’ll find it confusing. Then you’ll do some mental work, add your own portion of the narrative, and it will make more sense.

This is how you know you’re dealing with a postmodern work.

How is postmodernism different from what came before?

REALITY IS less CERTAIN THAN WE THINK

Postmodern works challenge the idea of things as complete entities.

Analysing a postmodern work involves deconstruction. To deconstruct an idea means to look at the final idea and at what created that idea. What assumptions do readers bring to the work? What are the parts that make it up?

Deconstructing a work of literature is akin to starting with a great Lego creation then taking it apart to see how many blocks are used and how they fit together.

A new postmodern mistrust of appearance has been necessary in the quest towards gender equality:

The conflation between woman and house began to seriously break down in the postmodern era, beginning approximately in the Vietnam War years of the later 1960s. The postmodern period is characterized by an intense eclecticism where no single style prevails in either dress or interiors. It is also characterized by a strong distrust of appearances; we no longer believe that what is projected is necessarily substantial. The presentation of self now relates to “lifestyle,” a cultural construct that is by definition fluid and superficial.

Beverly Gordon, Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age, 1996

Meaning is not inherent TO THE WORK

Another reader will get something different from a work of art. The meaning does not exist within the work, but is derived via an interpretation of it. Each interpretation is therefore valid. The works on the ‘canon’ are therefore challenged. All works now have validity. This also brings a lot of ambiguity and irony. There are layers of meaning. We have to keep drilling down through the layers to find out what something means. A movie like Shrek has a lot of layers of meaning through it — much of which is superficial and humorous — but it makes pop-culture references and weaves them into a reversed traditional tale. [Inversion does not equal subversion, which is much harder to achieve.] To subvert something means to cut away what people would expect to be the stable elements.

NON-LINEAR NARRATIVES

Stories come in a variety of different shapes. The straight shape is the linear one, based on the ancient mythic form. Postmodern works don’t tend to make use of that one.

Postmodern plot shapes tend to take readers back and forth in time, and often include other strands (sometimes called subplots). These subplots add to the theme, perhaps by contrasting with the main narrative. Postmodern narratives work on several different metadiegetic levels.

Voices In The Park by Anthony Browne includes four separate stories which only form a complete and interesting narrative once the reader has compared and contrasted the stories of each character.

SARCASM OR SELF-MOCKERY

Postmodern picturebook frequently feature a sarcastic or self-mocking tone. This is more clear in David Weisner’s books than in Anthony Browne’s. The sarcasm in a postmodern picturebook is not the negative, mocking kind, but playful and intertextual.

The Stinky Cheese Man by Scieszka and Smith (1992) is an excellent example of a sarcastic, self-mocking postmodern picturebook.

Jack uses narrative knowledge, not quick feet, to challenge the giant. He tells a story; but the story is an ever-repeating tale that creates a narrative trap, thus freeing Jack to run away as the giant is tied up in the endless words of the story. The degree to which the giant becomes lost in language is also expressed on the page through the size and contours of the font. In this case, Jack’s repeating tale grows smaller and smaller with each retelling until it is so small it cannot be easily seen — or heard. The increasingly small font not only suggests the Giant’s entrapment, but also the distance Jack has gained between the giant’s table and freedom.

A Unique Visual and Literary Art Form: Recent Research on Picturebooks

The audience may be a part of the joke or even the butt of the joke. In Shrek so many things are parodied: the children’s world of fairytales, the adult world. Intertextuality runs throughout Shrek (based on a picturebook by William Stieg).

However, the ‘sarcastic’ and ‘self-mocking’ aspect of the definition might need a bit of expansion in light of a (general, well-researched) difference between masculine and feminine approaches to humour. Feminine humour tends to focus less on the ‘self’ and more on the group, which may suggest ‘self-mocking’ is slightly more masculine.

POSTMODERN PICTUREBOOKS ARE SELF-REFERENTIAL

Self-referential describes text which reminds readers that the book itself is an object which has been created.

Chris Van Allsburg includes the same dog across all of his work.

Anthony Browne also refers to his other books within the illustrations. These function as Easter eggs for readers and are a metafictive device (reminding us that we are reading a work of art, pulling us out of the fictional world).

In The Three Little Pigs by David Wiesner (2001), pigs jump out of a pedestrian version of this fairytale and into a more exciting story.

Postmodern works are often METAFICTIVE

Metafiction is fiction which is conscious of itself as a created artifact. [David Beagley mentions that metafictive works don’t take themselves too seriously, though I’d argue plenty do.]

Postmodern works are a ‘discourse‘. Storytellers create meaning via a back-and-forth between readers via the work itself. If you read the same thing ten years later you will read a different story within.

With postmodern picture-books, the reader “enriches and supports the storyline by infusing personal emotions and experiences but also actively creates parts of the narrative.”

Goldstone (2002)

In postmodern works, audience becomes accomplice. The specific kind of interactive reading that happens between pictures, text and reader has been called interanimation.

Is any metafictive book Postmodern? Or does it depend on how much deconstruction is required on the part of the reader? Can Postmodern books exist for the early reader-preschool set? Is the existing criteria for Postmodern picturebook too narrow and too skewed towards a masculine sense of humour and a masculine way of seeing the world?

METAFICTIVE BOOKS ARE NOT ALWAYS POSTMODERN

Metafiction does not do any one single thing. Like the different media utilised by artists, or all the different forms of figurative language utilised by writers, a metafictive device is yet another tool in the storyteller’s toolbox. A highly metafictive picturebook such as This Book Just Ate My Dog by Richard Byrne is not Postmodern simply because it turns a book into an object. That book, for young readers, is a complete entity in its own right — a clever gag, with the gag dependent upon a metafictive device.

This Book Just Ate My Dog does not encourage readers towards a Postmodern relationship with the text. Once the story is over, it is over. Like any successful gag, the reader will understand it after a single reading.

POSTMODERN PICTUREBOOKS ARE ANTI-AUTHORITARIAN

All carnivalesque picturebooks are anti-authoritarian, but not all postmodern picturebooks are carnivalesque. You won’t find postmodern work which conveys the message adults are the authority and we should always listen to the adults. Quite the reverse. Fictional children must pay close attention to the world around them and work things out for themselves. By encouraging child readers to closely examine the text and pictures, postmodern storytellers are teaching real-world children to do the same.

What are postmodern picturebooks for?

Postmodern picturebooks upset the taken-for-grantedness of things. They do this by defamiliarising the audience.

For example the storyline of a postmodern picturebook might meander all over the place and never actually finish. Or it might stop suddenly and you’re not quite sure what’s going to happen next. Like a number of lyrical short stories, a postmodern picturebook may offer no sense of closure.

Postmodern picturebooks teach readers to pursue the interrelationships that storytellers create between words and text. They teach children to look for the space between. They encourage children to bring their own experience and thoughts to the story. They teach children that there is no authority greater than their own minds.

All good works, postmodern or not, require readers to bring their own prior experiences to the page and arrange new stories on an existing cognitive hanger.

Postmodern work goes beyond this. If the reader does more work. The story will feel incomplete without their cognitive input. The universal story structure necessarily apply so neatly to postmodern work, until we count the portion contributed by the reader.

The difference between Postmodernism and Surrealism

Elements of postmodern picturebooks may be Surreal.

Surrealism is used wrongly in everyday speech (meaning: I don’t get it, I don’t understand), but in an academic sense it means almost the opposite: Surreal is an abbreviation of ‘super-real’, in which we do understand a surrealist work of art by going past the surface and looking at the essence behind. The idea you achieve after digging for it is more important than any conveyed by the first impression.

Surrealism, like postmodernism more broadly, makes the viewer do work.

A dinosaur dressed in a hat driving a car is Surreal. This is also an example of hat-on-a-dog humour, which young children love. So there’s no surprise picturebooks lend themselves to Surrealism. Humour is rampant across Surrealist picturebooks and children’s films.

All this to say, children’s books are as intellectual as books for adults. They expect the reader to exert as much mental effort as an adult book does. Quite often, they require far more, because the reader does not have the contexts (and therefore the limits) that an adult reader has. In general, children are more able to let their imaginations go, and engage fully in ludic reading.

POSTMODERN PICTURE BOOKS AND PICTURE BOOK APPS

It is thought that when a postmodern book is remediated as an app, the postmodern effects may be rendered null due to the change of medium. The following aspects of postmodernism may not work very well in apps because in order for postmodern techniques to work, the reader must remember they are reading a book:

- Indeterminacy: there are ambiguities because there is a lack of information or too much information

- Reverberation: the story echoes other stories or material. In its more extreme form the result is similar to a collage

- Short-circuit: happens when the narrative communication hierarchy is altered

- Play: if the important thing in the story is to enjoy the signifiers rather than the signified, or the work considers the reader as a player

David Beagley from La Trobe University gave a lecture called Genres In Children’s Literature: Lecture 05: Postmodern Picturebooks (no longer available online). The notes above draw from that lecture.

WHAT IS POST- POSTMODERNISM?

Post postmodernism is a response to postmodernism. In his book aboout Jonathan Frnzen, Stephen J. Burn claims that The Twenty-Seventh City, Strong MOtion and also The Corrections (though more conservative) should be considered post-postmodernist.

David Foster Wallace and Richard Powers are also considered post-postmodernists in the same book.

POSTMODERNISM AND CONTEMPORARY RADICALIZATION

This is why people like Jordan Peterson use phrases like “postmodernism” and “cultural Marxism” in the same breath as “Satanism”—we are in a far scarier stage of societal radicalization than we’ve fully begun to contend with. They aren’t joking or overstating, they mean that.

@AlexArrelia