**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Postcard” is a short story by Canadian author Alice Munro, first published in Dance of the Happy Shades, Munro’s first short story collection (1968). This one’s about a player, and his unwitting bit-on-the-side who thinks he’ll eventually marry her.

Alongside “Thanks For The Ride“, the far more recent “Axis” and various other stories by Alice Munro, “Postcard” encapsulates the no-win situation in which young women found themselves during a time of great social change, which had a sexual revolution at its heart.

But this short story remains relevant to contemporary audiences. The West is going through another sexual (and gender) revolution right now. But due to the sorry state of last century’s women’s rights, Helen of Munro’s 1960s short story is left economically as well as socially unmoored when she realises, far too late, that she’s put all her eggs in the wrong basket.

Munro uses the metaphor of a postcard because there were no words to describe modern dating phenomena such as ghosting, simmering, icing and pocketing. This story remains relevant because such practices have, unfortunately, become more normative. Marriage expectations have also changed.

Using this story, let’s take a look at how.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

- The first person narrator of “Postcard” is called Helen. She’s a working class woman who works as a shop assistant at King’s Department Store. As usual, Alice Munro has carefully created a dynamic which avoids a simplistic, binary dynamic we’ve all seen hundreds of times before: an innocent woman is wronged by a no-good man. Munro avoids this simplicity by showing us that Helen has her own mercenary reasons for her interest in Clare. Sex with Clare is a bartering process. She has also (mal)absorbed some toxic ideas around women and dating to the point where readers can almost understand why Clare reaches the point where he considers Helen unmarriageable.

- Helen Louise (as she’s known only at home) lives with her Momma on the outskirts of Jubilee, a small fictional Ontario town based on two towns from Alice Munro’s own life. Momma knows what’s what. She tells Helen that “we’re as good as them [the MacQuarries]”, which alerts readers to the reality that Helen and her Momma are not considered as good as the MacQuarries. Alice Munro also slips in that Momma and daughter are isolated in this town—relatives live in faraway Winnipeg.

- Clare MacQuarrie is the name of Helen’s boyfriend (readers may associate this name with femininity). His body is slightly rounded. His round, balding head makes him a perpetual baby. Helen even uses the phrase “naked as a baby”. He’s not a good lover. He doesn’t expect participation from Helen. Worthy of note: Alice Munro has given Clare typically feminine attributes (a feminine name plus a soft roundness) which would ordinarily devalue him in the marriage market. Helen may think this too, at her peril, because 1960s white men hold a different hand of cards. (Again with the cards.) In fact, he’s better described as the manfriend, as he’s a full twelve years older than Clare. This places him almost in the dating demographic of Helen’s mother, and partly explains the flirtatious thing they’ve got going on between them. Snagging a wealthy-enough husband isn’t just a snag for Helen, of course. It would mean social security for her mother, since there’s no economic security for old, unmarried women otherwise.

‘Androgynous’ names, which may be given to both boys and girls, do exist (current examples include ‘Cameron’ and ‘Tyler’), but they are marginal. A study which tracked their use in the US state of Illinois between 1916 and 1995 found that they never accounted for more than about 2% of all names. One reason for this was their instability: over time they tend to lose their androgynous quality. In the early 20th century ‘Dana’, ‘Marion’, Stacy’ and ‘Tracy’ were all androgynous; but as they became more popular with the parents of daughters, they fell out of favour with the parents of sons. As a result, they have all become girls’ names. There are no examples of a name moving in the other direction, and this reflects the basic feminist insight that gender isn’t just a difference, it’s a hierarchy.

feminist linguist

- Porky (Isabelle) is Clare’s sister. Helen thinks (readers understand, correctly) that Porky doesn’t like her. Porky probably knows what’s going on. Perhaps she despises loose women like Helen. Or perhaps it’s simply easier to despise Helen than to sit with the dissonance required of her: She knows her brother is cheating on Helen, so it’s easier just to despise Helen. Clare, of course, tells Helen that Helen is imagining the animosity. (Today we call this gaslighting, but the film gaslighting goes all the way back to 1944, and I’m in no doubt that Alice Munro has long understood the dynamics of coercive control.)

- Porky has joined the normative lifestyle by marrying someone called Harold.

- Willa Montgomery is the woman who cares for old Mrs MacQuarrie, who is paralyzed down one side after a stroke. Blink and you miss it, but Helen tells us she cares for the old woman by day and for Clare by night.

- Ted Forgie is an old beau of Helen’s who wrote her love letters and worked as a radio announcer. The reader, like Helen, will be left wondering if she should’ve married him instead of waiting around for Clare. The character of Ted exists to show that romantic opportunities were there, but have since narrowed down to just Clare.

- Alma Stonehouse is the friend who tells Helen what Clare has been up to in Florida. A school teacher at the local public school, she’s wary of men after separating from a man who continues to write her nasty letters. She came equipped with tranquilizers, or barbiturates known as “Mother’s Little Helpers” back then. Alma says they’re not very strong’, suggesting she’s built up somewhat of a resistance.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “POSTCARD”

There’s another Helen in this collection: the girl in “Day of the Butterfly“, slightly ostracised from her school community because she’s rural. Is this the same Helen but grown? Impossible to say. She could be, but Alice Munro re-uses names. Take the name “Flora”, which Munro uses a number of times across different stories, including once for a horse.

If this is the same Helen, she’s grown from a quietly caring and observant girl into a more strident woman. Her friend in primary school died of leukemia and Helen felt helpless at the time, affected in a way other children didn’t seem to be. Helen has since made other woman friends, but she remains on the outskirts of town’s, let’s say, clubbable members.

She must be in her early thirties by now. And still not married. Mm-ahh. A social no-no for women. All the Good Men were snapped up a decade ago. Don’t you know that even if you’re lucky enough to attend a university, your main job as woman is securing a husband? You should have at least a couple of children by the time you hit the big three-oh. Your looks are on the downhill slide.

KING’S DEPARTMENT STORE AS FORESHADOWING

Alice Munro opens with a surprisingly detailed description of King’s Department Store, where she’s been working ever since she left school. On the surface, all of this detail may seem superfluous, but by describing the shift that was happening in the change from personalised grocery stores (with grocers who knew everybody) to impersonal stores owned by town-outsiders, she is telling the story of another cultural shift: the parallel shift that was happening in dating. Before, Clare wouldn’t have got away with such poor behaviour in the small town of Jubilee, because everyone knew each other and had tabs on each other as well. But the culture has shifted. It’s now possible for wealthy people to fly off to Florida and get away with all sorts, like the equivalent of a store owner who you never see.

Ironically, Helen works in the children’s section of this department store, selling clothes to mothers with no real prospect of ever becoming a mother herself.

Unironically, the clothing department is upstairs. Helen is soon revealed to have been Clare’s archetypal Woman Upstairs (or mad woman in the attic), and the story ends on a display of madness—perceived as ‘crazy’ because of her gender, but what is in reality a cathartic and necessary outworking of rage.

THE POST OF POSTCARD

Note that the “post” in “postcard” does double duty: Helen is past (post) the time she is expected to be settled down. The break-up tragedy of this story is more tragic given the era. This isn’t your ordinary (contemporary) dumping.

“Post” means “after” in a general sense, and so readers are encouraged to linger on what will happen to Helen after. Of course, she’s already living in the ‘after-times’, only now she knows it.

Helen has not missed the marriage memo. She knows full well that she’s supposed to have snagged a steady man years ago. However, she kind of has? All through her twenties she’s rested safe in the embrace of her man, who totally plans to marry her, but only once his old mum kicks the bucket.

HELEN THE GHOSTED GHOST

In the interim, Helen must stay on the down-low. She can visit Clare at his house (where he still lives with his elderly mother), but Helen must exist as a ghost. The mother can’t know she’s there. Note how Alice Munro has created a ghost of a character in line with modern parlance, which also uses the term ‘ghosting’ to describe cutting someone off without communication.

WHY WOULD CLARE BUY THE COW?

Helen’s own mother isn’t too happy with her daughter’s romantic arrangement. Momma’s of the “why would he buy the cow when he’s getting all the milk” variety.

“Once a man loses his respect for a girl, he is apt to get tired of her.”

“What do you mean by that, Momma?”

“If you don’t know am I supposed to tell you?”

“Postcard” by Alice Munro

Momma has internalised the misogyny, but is she wrong?

Turns out no! Momma was right about the guy, who does a despicable thing by any measure. While away on holiday in Florida Clare sends Helen a postcard telling her he’s having a wonderful time, when in fact he’s marrying some other woman.

It’s almost worse that he sent her a postcard and still didn’t tell her. Ghosting would be a mercy. This is some heavily extended breadcrumbing. (See below.)

Note that even Helen’s mother hasn’t been straight with her own daughter. “Am I supposed to tell you?” All of these ‘rules’ around dating and marriage are unwritten. The mother must have assumed Helen had absorbed them perfectly. In fact, Alice Munro gives readers enough to realise that Helen did not, in fact, understand the extent to which she was giving away more and more her good cards with every passing year.

Later, as the story draws to a close:

All the houses in darkness, the streets black, the yards pale with the last snow. It seemed to me that in every one of those houses lived people who knew something I didn’t.

“Postcard” by Alice Munro

What is the ‘something’ Helen didn’t know? Not just the fact that Clare was two-timing her. She didn’t fully understand that her time was running out. She didn’t understand that the rules are different for women, especially poor women.

Her other main flaw? Thinking herself too worthy. Ironically, the mother has been instilling in Helen that the pair of them are worthy. These conflicting messages having gotten Helen into this mess. Even worse? Years earlier, Momma warned Helen off a decent romantic prospect.

CLARE’S DESPICABLE ACT

Rather than tell Helen about his marriage to another random woman who Helen’s never met, Clare just lets her find out about it naturally, in the worst possible way: His marriage is announced in the local newspaper. Smalltown humiliation at its peak. Helen’s girlfriends know about the marriage before Helen does.

Then the entire town knows. Helen feels everybody is up in her business. It is a humiliation having to go to work, where she must face nosy customers. She feels their silent judgement, and also looks down her nose at an older woman who was jilted (just like she was), married late and was left once again. Helen is looking at her very own future when she looks at Mrs. Kress.

Her best friend rushes round to share the news and offer sisterly consolation.

Helen is, understandably, ropable. She’s been strung (roped?) along for a decade. For a man, to be at square one on the marriage market in one’s early thirties is no big whoop. His virility lasts much longer. But for Helen, her newly single status means a completely different life trajectory. She’s now a spinster. What’s more, she’s not even a virgin spinster. Plus she has no family money. Her prospects of leading a normative life as a wife and mother are next to nil.

Munro exhibits a tense preoccupation with women who are toyed with by men of means––those chosen first and then rejected for a more “suitable” mate, or subjected to seductive acts of courtship that never come to fruition. These women always face a world in which they have little power to direct their fates, but persist with a quiet strength that subverts––sometimes successfully and sometimes not––the tragedy of their cultural and economic relegation.

from a consumer review, subsequently mentioning “Friend of My Youth” as an example

Here’s an excerpt from a far more recent story, showing that this attitude regarding women and age-of-marriage is far from dead, even if we dare not speak of it out loud. The expectation hasn’t died across all cultural groups:

My twenties were spent in school, and a girl in her twenties is said to be in her prime. After that decade, all is lost. They must mean looks, because what could a female brain be worth, and how long could one last?

Being in school often felt like a race. I was told to grab time and if I didn’t—that is, reach out the window and pull time in like a messenger dove—someone else in another car would. The road was full of cars, limousines, and Priuses, but there were a limited number of doves. With this image in mind, I can no longer ride in a vehicle with the windows down. Inevitably I will look for the dove and offer my hand out to be cut off.

the opening to Joan Is Okay, a 2023 novel by Weike Wang

WHY DID CLARE DO WHAT HE DID?

The reader is left to conjecture why Clare would do such a thing to Helen. For that, an understanding social context is important.

Alice Munro has given us enough information to deduce that part of the reason he won’t marry Helen is fiscal. She’s of a lower class than him. Her willingness to have sex with Clare before marriage only proves his misogynistic point. The double standard applied to women is in fact a double bind, which means Helen can’t win. Alice Munro reminds us of the double standard when Clare writes on his postcard, “Be a good girl,” which has more enraging resonance after some delayed decoding.

The double bind: Leaving aside the reality that most adult women require partnered sex as a fairly basic need, this man wouldn’t be interested in “dating” Helen if she weren’t having sex with him, and he isn’t interested in marrying Helen precisely because she is.

Needless to say, there’s also a strict mid-century gender hierarchy at play, in which men hold the cards. Ultimately, men do the choosing, especially after a gender imbalance exacerbated by postwar loss of soldiers, and the glorification of virile masculinity.

But the West was, at the same time, also going through a sexual revolution which encouraged disposability around sex:

[Dance of the Happy Shades] may at first glance appear to be out of step with its time. After all, this was the year of the May events in Paris, student uprisings across Europe, massive anti-Vietnam war protests on both sides of the Atlantic. In music, Jimi Hendrix spent months reworking Bob Dylan’s bleakly minimalist All Along the Watchtower into his stunning, apocalyptic version of the end of things, and everywhere Dylan’s prescient words about the overthrow of the old order––in politics, culture, society––seemed to be acquiring the force of prophecy. From Munro’s home country of Canada Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Neil Young were all emerging at this time.

a reader review at The Short Review

This ‘disposability’ proved a massive problem when basic women’s rights were yet to be won. Disposable sex partners ultimately meant disposable women. This is the social environment Alice Munro explores. If we read “The Peace of Utrecht“, another story in the same collection, the sister who returns from the big smoke to Alice Munro’s fictional small town of Jubilee is surprised to find that the adults who stayed in this rural backwater of a town have, surprisingly, adopted far more big city attitudes and fashions than the narrator had expected. We can deduce, therefore, that young adults of Jubilee, where Helen of this story also lives, are likewise influenced by the Swinging Sixties, more typically associated with cities.

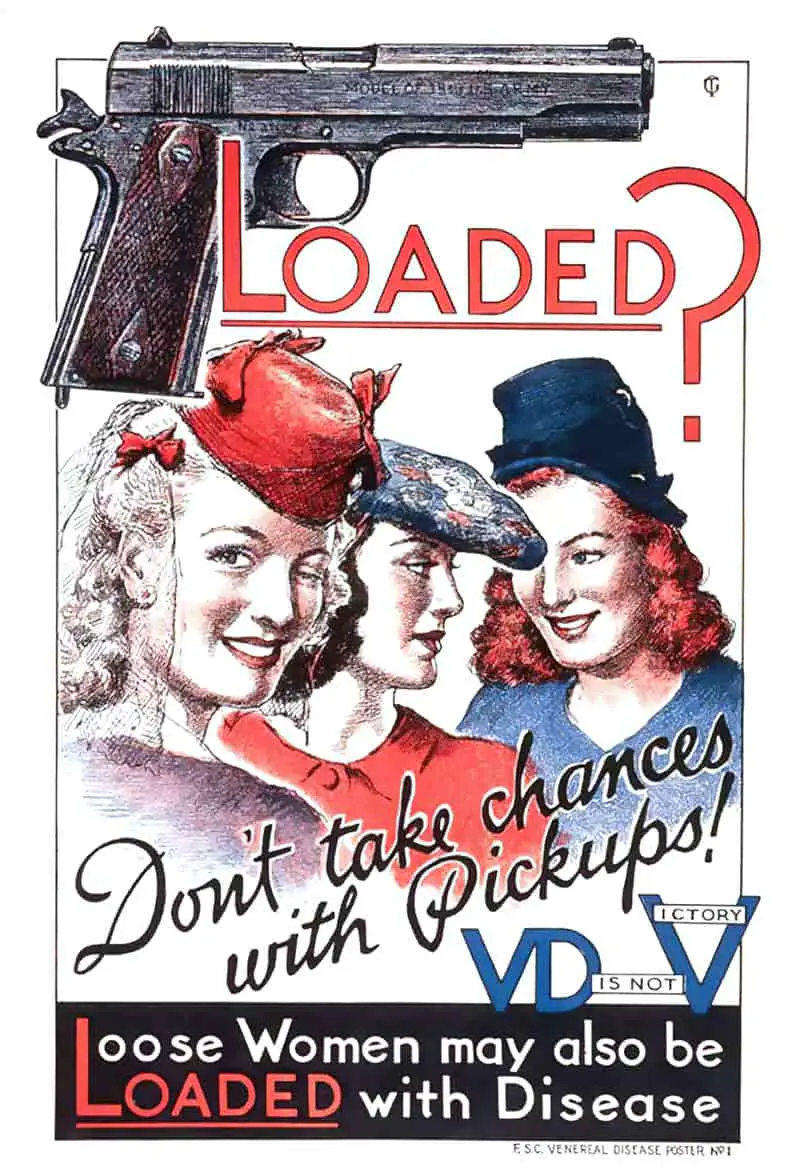

Also, Clare was a man of his era. No excuse, just fact. Everyone in the postwar era, not just men, had been bombarded with war propaganda such as the following:

Sexually active women were a locus of disgust. Nay, any woman straight men found attractive could serve as a locus of disgust, whether she looked like the girl next door (above right), or like a winking, ostentatiously-hatted, hair-dyed vixen (above left). Women were disgusting even as men continued to feel attraction for them. In fact, disgust is oftentimes part of the attraction. Acculturation can make it so.

So that explains why Clare might find Helen disgusting and unworthy of marriage. He finds her attractive, plus she’s having sex with him. But why wouldn’t he at least tell Helen himself, about his marriage?

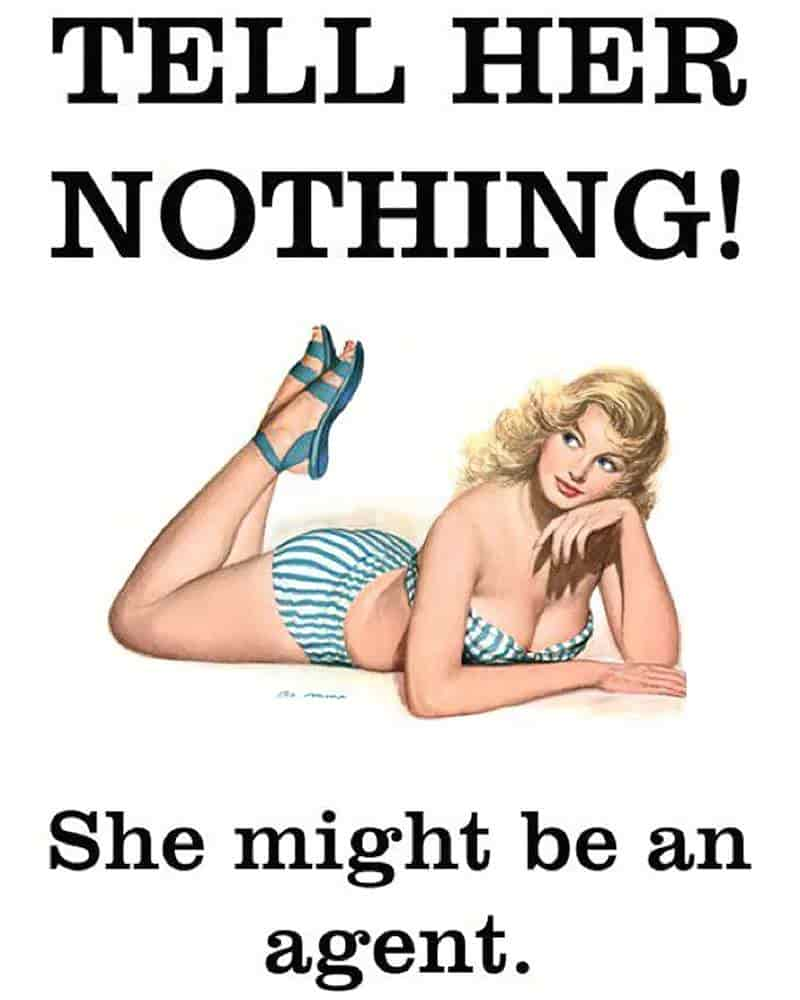

Again, we can easily find wartime propaganda which teaches that women, as a species, aren’t really worthy of ‘telling things’. Whatever targeted messages were distributed during the war—ostensibly regarding the specific type of woman known as honey trap spies—worked a charm. Why would a man trust any woman, for that matter? Especially one who he finds sexually attractive. Any woman might be a ‘trap’, if not because she’s a spy, then definitely because she might ‘get herself’ pregnant. That would trap him into marriage. (Alice Munro explores the cultural forces around this in “Thanks for the Ride“. The mother of this story courts the eligible bachelor in the same way the mother of “Thanks for the Ride” courts the 18-year-old virgin.

If a man was having sex with a hot woman and they weren’t married, posters such as the one below taught him well: he had carte blanche to TELL HER NOTHING!

Then there’s the basic fact of Clare’s sexual entitlement. He’s no doubt hoping to marry the other woman and keep Helen as his bit on the side. Importantly, he has never promised marriage to Helen. Helen feels simply that “it is understood”.

Helen has made a grave error: She perceives herself as a worthy woman, when the world does not perceive her that way.

Eventually, Clare does ask Helen to marry him, but in hindsight this feels like part of their game. Alice Munro may also be commenting on another ironic dark side of enforced chastity for women. Helen seems to have absorbed the cultural script that to secure a man you keep him chasing. But she’s got it a tiny bit wrong. Keep him chasing you for sex. Don’t give him the sex and keep him chasing you for marriage.

The other thing she’s got a bit wrong: By waiting a few years before bringing the topic of marriage up again, she’s already past her use-by date. This appears to be Munro commenting on the ridiculously tiny sliver which is the young woman’s marriageability window. Mess around at your peril.

There are numerous rules around ages, mostly unspoken. Momma was against Helen seeing Ted Forgie because he was too old for her at the age of 24. She does not apply this standard to Clare, we deduce, because a man of great means (someone who goes to an exotic place for vacation every year) can do what he likes whenever he likes.

THE ENDING

As the story ends, Helen is full of passion. Mostly rage. But the opposite of anger is indifference. Her attraction to Porky remains. Readers are left to wonder if Helen will choose to go along with Porky’s plan, which is continued sexual access to loose-girl Helen while married to the future mother of his children.

Why does Alice Munro bring out the local policeman, to tell Helen off for being a public disturbance?

My take: The policeman serves as The Village Voice. This is exactly how people, in general, will feel about Helen, denied the right to anger because she made the Wrong Choice. She should’ve stayed a virgin until marriage.

It’s also significant that the policeman is younger than Helen. This reminds readers of Helen’s age. She’s older in years than the night constable who is taking on a patriarchal tone with her. Even his name, “Buddy”, infantilizes him. To top it all off, she’s being chastised by a kid she used to teach in Sunday school. (Even Buddy’s last name, Shields, feels symbolic. Buddy is the self-designated patriarch, shielding Helen from further humiliation.)

Remember how Clare, too, was infantilized, with his roundness, his baldness, his naked-as-a-baby-ness? Something significant is being said here about the perpetual right of men to remain in suspended childhood. Buddy the night constable, like Clare in his postcard, tells Helen to be a ‘good girl’. Men are at once afforded the privilege of remaining babies while simultaneously drawing down on their assumed authority, afforded by the gender hierarchy we call patriarchy.

In contrast, women age fast, faster than Helen ever realised because no one ever said the quiet part out loud. Yet old women garner none of the authority which come to men as men age. This was Helen’s realisation. This is why she rages. Reclaiming a final bit of girlhood, she tries to draw Clare out of his marital nest by yelling at him an old playground taunt, partly improvised:

Clare MacQuarrie for nuts-in-May If he don't come out we'll pull-him-away!

THE STORY WITHIN-A-STORY

Buddy the young night constable gets into Helen’s small car, gifted to her by Buddy two Christmases ago, and drives her home (without her permission). As they drive he tells her a story about another philandering couple who he helped out of a tight spot just recently. Comically, he gives Helen all the information she would need to know exactly who it is. This is a very small town, clearly, and everyone has been shown to be all up in everyone else’s business. He means Helen to bury the shame of her dumping like everybody else.

So Helen has learnt something else: There are many sordid secrets in this small town, many snails under the leaf, or “mould under the linoleum”, as may be more fitting for an Alice Munro story.

And so the story ends on a note of universality. This is the fictional town of Jubilee, but could apply to any community anywhere: Many private tragedies, happening behind closed doors, where people transgress the unwritten rules which somehow everyone is supposed to know the ins-and-outs of.

GHOSTING, SIMMERING AND ICING: A MODERN TAKE ON A VERY OLD DYNAMIC

The word ‘ghosting’ is fairly well established in 2023, especially after well-known psychotherapist Esther Perel wrote about it. (On Perel’s website you can find a Relationship Accountability Spectrum.)

What about ‘simmering’ and ‘icing’? These are slightly different out-workings of the same thing. Instead of cutting you off completely, someone keeps you in limbo:

SIMMERING: “I’m really busy, but let’s stay in touch. See how things go.” This way I can maintain the freedom of a single life, but I also don’t have to bear the possibility of winding up completely alone. I’m afraid of being alone, but also I don’t have the guts to end things. I can’t be with you, can’t be without you.

ICING: “Hey! I’ll be really busy (with work/family) for the next three months, but don’t disappear on me! I really like you.” Stay in the background. That way, when the ‘ice’ melts, when the season changes I may come back. Or I may not. I’m keeping my options open. Icing is also known as BENCHING, making use of sports terminology. Someone is keeping you ‘on the bench’ while they try out other dating options.

POCKETING: When a newish partner avoids introducing you to any of their friends and family, or announce your relationship on social media. This could mean a number of things. If they don’t announce the relationship on social media, this could simply mean they’re not much on social media, they are a private person in general, or they like to keep their private life offline. However, if they’re also refusing to introduce you to the closest people in their life, this can be cause for concern. Australia’s ABC dating podcast “The Hookup” has an episode on this, including what to do if you realise you’re being pocketed. Helen of “Postcard” hasn’t been pocketed. The entire town knew that she was Clare’s girl, or one of them. They ate together at the Queen’s Hotel and whatnot. Helen met his sister and brother-in-law.

BREADCRUMBING: Flirting with someone with no intention of starting any sort of committed relationship. Today breadcrumbing is very easy to do because we can just use our phones to do it. Importantly, you know you’re being simmered, iced or breadcrumbed because the unavailable person will make noises about meeting up ‘sometime’, but gives no specifics regarding date or time.

As Esther Perel explains, these ‘dating techniques’ may feel fine for the person putting another on the simmer, or keeping them in their pocket, but for the object of (in)attention, any anticipation and excitement very soon morphs into horrible anxiety.

Perel has a phrase to describe this state of mind: stable ambiguity. Being on the receiving end of such behaviours is highly destabilising. We see this happen to the main character of “Postcard”, as Alice Munro gives a woman a (very loud) emotional breakdown at the end, then leaves her in a state of ambiguity: She can’t stand this guy, but also wants to be with him.

Stable ambiguity is just ambiguous enough that you end up becoming very destabilised, actually.

Esther Perel

The terms to describe such behaviours were coined after the proliferation of online dating. No coincidence there. As Alice Munro’s 1960s short story illuminates, simmering, icing and ghosting are as old as the hills, but there is now a jarring switch between, say, 250 text messages per day, to absolutely stone cold nothing.

Before technology allowed for constant and effortless communication, dating tended to progress much more slowly. Let’s go back quite a ways, and take an example from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. The dating rules of that social milieu were circumscribed, strict and widely understood:

- Your father visits the romantic prospect to say hello and let him know he has an eligible daughter (or several!)

- The romantic prospect returns the visit, staying no more than 15 minutes. (In Pride and Prejudice it means something that Mr Bennet spends only 10 minutes with Bingley––he has cut the visit short because he has no real interest in his daughters’ economic/marriage stability.)

- Visits thereafter may happen in public such as at the local assembly hall.

- In private, the young women are chaperoned until such a time as the man proposes (and even then, your mother probably has her ear pressed to the door).

Pride and Prejudice does contain a famous literary example of ghosting. Bingley ghosts Jane. But of course it wasn’t called that at the time, and wasn’t usual. Most people married within their own local area, and disappearing forever wasn’t even an option. Imagine how much worse it would have been for Jane if she’d been getting 250 texts a day from Bingley. As she tells Lizzie in private, the pair of them didn’t exactly have a contract. They barely spent any time together before Bingley left Longbourn at Darcy’s recommendation.

When Alice Munro published Postcard several hundred years later, there was still no widely-understood word to describe the phenomenon of ‘ghosting’, but I believe this entire story is about that. Munro uses a postcard as a metaphor for a type of (mis)communication in which one partner (often a woman) makes do with crumbs––as much as fits on the back of a postcard (in contrast to the deeper communication offered by, say, a letter inside an envelope). A postcard has no privacy. It can be read by anyone. Therefore, the postcard symbol also offers the illusion of transparency. The man who sent it is anything but transparent.

Ghosting, simmering and icing doesn’t just happen within the context of romantic and sexual relationships, but is part of a wider cultural change in how we interact:

And then you’ve got Gen X. They will have made the plans well in advance. And they would have also checked in a couple of days before, just to make sure the plans are definitely still happening. You see, Gen X are the forgotten generation. And they’re so scarred by this title they would have assumed you’d forgotten, not only about the plans but about their very existence.

Millennials will have hoped the plans would’ve been cancelled. There’s no reason a millennial will actually want to come to your house. They will arrive late, but they will text you to say they’re on their way. Just, they’re about to get into the shower. And a millennial will never knock on your door. You’ll just get a text saying either ‘here’ or ‘outside’. And that’s your cue to go and let them in.

Similarly, Gen Z will never actually knock. But chances are they won’t have to. They would’ve been documenting the entire journey from their house to yours, maybe even on Facetime using this angle [pans skyward] as they go along, for some reason. Either that or they’ll just send a picture of your front door or a selfie of them outside it. And again, just like the millennial, that’s your cue to go and rescue them from the outside world.

Capstone > Cornerstone Model of Relationships

Ester Perel helpfully explains the cultural shift which was happening just as Alice Munro published “Postcard”.

A cultural shift happened in romantic and married relationships between Baby Boomers and Gen X. This change happened during the late 1960s and continued gradually through the 1970s.

This change in dating happened in tandem with a move towards individualism, which is inextricably tied to capitalism. Capitalism is inextricably tied to choice and consumerism. When we are inundated with choice, happiness can start to feel like an elusive pursuit. How will we know when we’re happy enough? We apply this thinking to our (potential) partnerships.

In the West, for many decades leading up to the late 1960s, people believed that a marriage made you whole. But after this 1960s cultural change, Westerners started to believe that it was the individual’s responsibility to ‘become whole’ before seeking out a romantic relationship.

This shift is known as the change from the Cornerstone Model to the Capstone Model.

THE OLD CORNERSTONE MODEL

- In the early 1960s, 80% of people in their twenties were in a long-term relationship, if not married. (Today it’s 20%.)

- If you meet someone in your late teens or early twenties, you must grow together to stay together.

- When crisis happens, you overcome it together. This is considered a crucial part of building a strong long-term relationship.

- This is a Western, individualistic way of thinking. In countries like Japan, the cornerstone model endures.

- Advantages: This way of thinking avoids the trap of believing there’s someone better just around the corner because no one else in the world has built history and experiences with you.

- Disadvantages: If the relationship does dissolve, the people involved cannot draw on the experience of being alone as an adult. Simply being alone can be a terrifying thought.

THE NEW CAPSTONE MODEL

- According to a popular modern way of thinking about relationships, people plan to meet their longterm partner in their late 20s or early 30s.

- By this point, each partner will have already worked on building their identity. They know who they are and what they need from another person.

- Also, by working on themselves, they have made themselves worthy of love.

- When someone chooses you, that is considered a recognition of how well you have done.

- It is thought that when people meet in their late twenties, early thirties, they are meeting each other at their ‘most authentic’, which gives the partners more likelihood of being happy together long term.

- Dating is now an individualistic project.

- Now, relationships are not about growing together but about preserving the ‘authentic’ self one brought into the relationship.

- Advantages: If a relationship does dissolve, each partner in a capstone model is better equipped to be alone outside a romantic partnership.

- Disadvantages: Partners can be less prepared to work things through. Used to working alone, on themselves, it can be easier to leave a relationship than to compromise. In fact, compromise may be avoided as it’s seen as a loss of ‘authentic self’, which we idealise in this new model. And people who partner in their late twenties may have spent over a decade moving from one partner to the next. There’s this niggling feeling there’s someone more suitable out there for you.

WHAT DID THIS SHIFT MEAN FOR WOMEN LIKE THIS?

Helen is scissored between two cultural shifts. The man she’s been seeing has taken his sweet time partnering up, and is almost a caricature of a man who keeps his options open all through his 20s and early 30s until such time as he is no longer so marketable, and he’s about to move into a demographic which deems him less attractive to women of peak-fertile age.

Meanwhile, cultural attitudes towards women who have an equal amount of sex before marriage––i.e. towards grown-arse women in their twenties and early thirties who dare to have a partnered sex life––remain unchanged.

The shift from the Cornerstone Model to the Capstone Model happened before the shift in morality which allowed unmarried women to have sex without being labelled as dirty, disgusting and disposable.

If anyone continues to assert that Alice Munro is not a feminist writer, I’ll… I don’t know what I’ll do. Write a sternly worded blog post, I suppose. Or maybe, like the woman in this story, a cathartic scream will suffice.

FURTHER RESOURCES

Postcards: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Social Network

For this episode, I met historian and writer Dr. Lydia Pyne. She is author of Postcards: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Social Network (Reaktion, 2021). Postcards is a global exploration of postcards as artifacts at the intersection of history, science, technology, art, and culture. Postcards are usually associated with banal holiday pleasantries, but they are made possible by sophisticated industries and institutions, from printers to postal services. When they were invented, postcards established what is now taken for granted in modern times: the ability to send and receive messages around the world easily and inexpensively.

Fundamentally they are about creating personal connections—links between people, places, and beliefs. Lydia Pyne examines postcards on a global scale, to understand them as artifacts that are at the intersection of history, science, technology, art, and culture. In doing so, she shows how postcards were the first global social network and also, here in the twenty-first century, how postcards are not yet extinct.

New Books Network

DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses” — In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. They conspire to get rid of the old poultry-farming witch. Only our narrator seems conflicted.

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride” — This story is written with the viewpoint character of a young man. He has just finished school and is out with his older cousin with the purpose of losing his virginity. Together they pick up some ‘loose’ girls. The whole experience is perfunctory and defamiliarizing.

- “The Office” — A housewife decides to improve her life by carving out some time for herself to pursue her passion of writing. So she rents a room above a hair salon and drugstore. But the landlord won’t leave her in peace, deeming her time his.

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death” — A mother who lives in one of the squalid cottages on the edge of town has lost a child in a terrible accident. The village gathers round, but how genuine are they in their grief?

- “Day of the Butterfly” — Two girls at a primary school are ostracised. One is the narrator, now grown, ostracised for being an out-of-towner who doesn’t wear the right clothes. The other is more ostracised still, because her parents are immigrants, because she smells like rotting fruit, and because her brother needs her to accompany him to the toilet. When this girl is dying in hospital from child leukemia, the young narrator is filled with inexplicable grief. It is now too late to be a real friend to this outcast, and anything she does in kindness will feel empty and pointless.

- “Boys and Girls” — An outdoorsy farm girl loves helping her father on the fox farm but realises she’ll very soon be required to go indoors to help her mother with domestic work. In contrast, her younger brother, far less conscientious, will be allowed to stay outside and work with the animals, enfolded and welcomed into the masculine world.

- “Postcard“

- “Red Dress—1946” — A thirteen-year-old girl’s first ball. Her mother sews a red dress with a princess neckline. Suddenly she looks much older. She barely recognises herself in the mirror, and longs for childhood again. Almost all the girls around her are obsessively interested in boys. Everyone, that is, except one other girl who says she despises boys, and plans to support herself by working as a P.E. teacher. But by aligning herself with this queer girl, our thirteen-year-old risks much. What will she do? Will she take up the offer of friendship?

- “Sunday Afternoon” — Seventeen-year-old Alva has recently finished high school and started working as a maid for the mega-wealthy Gannetts. Today they are hosting a party at their mansion and Alva must navigate a delicate social situation: They want her to feel part of the family, but what does that mean, exactly, when you’re actually the paid help? Alva must also navigate the men who enter the house, several of whom express sexual interest in her. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill, predictable young-woman-is-seduced storyline, but Alice Munro keeps readers in audience superior position as we watch with bated breath what happens to Alva in this big, lonely island of a house. We’re left to deduce most of it.

- “A Trip to the Coast” — An eleven-year-old girl called May lives with her mother and grandmother (mostly her grandmother) in a general store in a three-house township. There’s nothing to do in this one horse town. But today she’s looking forward to same-age company. However, the “company” is a total let-down, and so her grandmother, for the first time ever, suggests the two of them take a trip to the coast. But then another visitor comes. A customer who declares himself an amateur hypnotist. This story ends on a cliff hanger, and I don’t believe Munro has given us enough of a symbolic layer to fill in the gaps for ourselves. I believe we’re supposed to feel exactly as unmoored as eleven-year-old May, waiting out front of the store in the rain.

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades” — An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke. The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these excruciating annual events.

REFERENCES

- Note To Self podcast: Ghosting, Simmering and Icing with Esther Perel