“The Possibility of Evil” is a short story by American author Shirley Jackson (1916-1965). Find it in several collections: Dark Tales and Just An Ordinary Day. The story was first published in The Saturday Evening Post a few months after Jackson’s death.

“THE POSSIBILITY OF EVIL” SUMMARY

An evil, busy-body old woman is a self-appointed vigilante citizen, predicting evil before it happens. She’ll do whatever it takes to prevent evil.

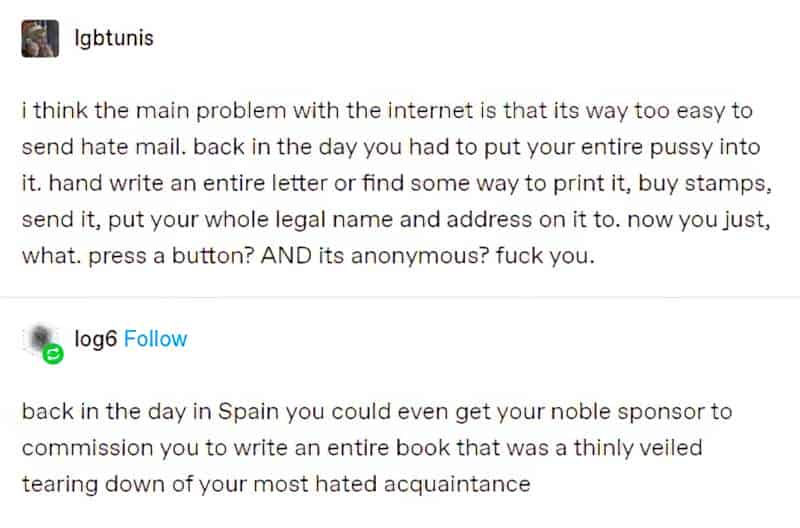

For the past year or so she’s found herself a hobby. Miss Strangeworth has been composing and sending nasty little letters, which she writes anonymously, faking a childlike hand. Miss Strangeworth is the 1960s equivalent of an Internet troll:

Miss Strangeworth never concerned herself with facts; her letters all dealt with the more negotiable stuff of suspicion.

“The Possibility of Evil”

Before the Internet, people with an interfering, opinionated, judgemental, vigilante mindset were creating evil in non-Internet ways — here, Jackson imagines such people at home — in their wealthy, beautiful homes, not in their mothers’ bsements — using deceptively stubby pencils and pastel-coloured notepaper.

Miss Strangeworth would rather be wrong about people than to say nothing at all. To her vigilance takes precedence over truth. In this warped way of thinking, vigilance and truth cannot be disentangled, since truth cannot emerge without vigilance. (Circular thinking)

Besides, she liked writing her letters.

“The Possibility of Evil”

The word ‘besides’ is ironic. This old battleaxe likes writing the letters and that’s why she writes them. There is no ‘besides’.

Alongside the best stories, “The Possibility Of Evil” contains a deeper irony at its very heart: Avoiding acts of evil requires evil acts.

THE SYMBOLISM OF CIRCLES AND SPIRALS

This story isn’t just ironic; it’s circular. As you read, notice how Shirley Jackson creates circularity throughout the narrative:

- A town which is such a closed system it appears to bend round on itself, imprisoning its long-term residents

- mechanistic activities which happen every single week, year after year after year.

- At a more granular level, notice emphasis on round objects e.g. the single tomato she Miss Strangeworth buys for her dinner; the ‘round hooked rugs on the floor’ of her living room; the plate and cup and saucer; bowls of roses (helping us subconsciously understand the things-inside-things-inside-things symbolism).

- Finally, the old woman’s sense of justice will spiral out of control.

All of this adds up to what we now call ‘circular thinking’.

For more on that: “Begging The Question” episode of the “You Are Not So Smart” podcast.

CHARACTERISATION OF MISS STRANGEWORTH AND HER TOWN

Wait up: Miss Strangworth is the town.

Miss Strangeworth has a beautifully descriptive name: Her take on value is revealed to be warped.

Shirley Jackson’s short story feels like an ancestor of The Truman Show (1998) and Pleasantville (also 1998). Miss Adela Strangeworth is proud to say she’s lived in this utopian town all her life. To her, the outside world does not exist.

This is Miss Strangeworth’s realm. She holds an (dimpled) childlike, solipsistic view of everyone else in the town. Jackson depicts Miss Strangeworth as an automaton, with mechanistically predictable behaviour. The woman can’t understand why the grocer man — who she’s known all her life — can’t remember which day she buys her tea. This is egocentric, but it also sets the scene: Everything works ‘like clockwork’. Miss Strangeworth cannot be separated from her setting.

Readers can deduce from Miss Strangeworth’s interaction with tourists that she feels the entire town belongs to her. She feels her ancestors founded the place. Without them, none of this beauty would exist. Forget gratitude, her ancestors don’t even get a statue! I’m sure locals are sick of hearing about it, so here she is, talking the ears off hapless tourists.

See also: How Can Setting Be A Character?

AN ALLEGORY OF WHITE ENTITLEMENT

“My people built this city! The rest of you are lucky to live here, but we will control how everything is run, and how resources are dished out. After all, without white endeavours, you’d all be living in caves!”

DARK SUBURBIA

Of course, in a Shirley Jackson story, with a street literally named Pleasant Street, readers sense early: this is an archetypal Snail Under The Leaf setting. Beneath the high-key veneer, everything is rotten. Notice how Shirley Jackson describes colour. There’s beautifully bright, then there’s lurid. (Australian author Tim Winton also uses the lurid colour motif in his short story “Big World”.)

ROSES AS CHARACTER MOTIF

A characterisation trick: Attach an item to a character. Make it symbolic.

For Miss Strangeworth, this is roses. She is especially proud of the mass of roses growing outside her house on Pleasant Street.

Why roses? The flowers look nice. The smell nice. But they are also barbed. This part of the rose symbol can be seen across narrative and is common. Less obviously, and specific to this particular narrative: The mise en abyme effect you get looking into a rose. The petals grow as if to form a never-ending spiral. The roses seem to have mesmerised Miss Strangeworth, drawing her into this circular, spiral thought-pattern, leading to catastrophe.

HATS AS CHARACTER MOTIF

The large hats draw all the main symbols around Miss Strangeworth together: They are round, women’s hats can be decorated in roses and hats are a symbol of power. The more expensive the hat, the more powerful you are. Miss Strangeworth has inherited her hats as she has inherited her white economic privilege. That she still values these hats holds her firmly in a former era. She would prefer to live forever in that era, experiencing the same year over and over rather than joining the march forward. The circle of roller-skating children at the end underscore the reality that Miss Strangeworth is the last of the Strangeworth line. It is with desperate fervour that she wishes time to stand still.

“The Possibility Of Evil” really was a 1965 story, wasn’t it?

THE ENDING

In the end, Miss Strangeworth drops one of her letters, children see her drop it and the whole town is about to learn how nasty she is. For now, someone exacts revenge on the old lady’s precious rose garden. The narrative mask has come off.