Poof The Old Lady is a graphic novel created by two neurodiverse ten-year-olds. The running gag is that an old lady by the name of Poof goes Poof! at the end of each story. But she comes alive before the next.

The creators are best friends at school, and they both like to read and watch cartoons. They count among their favourites:

- Courage The Cowardly Dog

- Dog Man

- Diary of a Wimpy Kid

- Ahn Do, Weirdo

- All of these picture books and more

- Superhero stories such as Spider-man and Teen Titans, Go!

- Pixar and DreamWorks films

- Raina Telgemeier’s graphic novels

- Spongebob Squarepants

One of them loves dogs; the other loves owls. One has neat handwriting and is tidy by nature; the other can write and draw well, but her work is inclined to degenerate into scrawl, as ideas come faster than execution.

Telling stories is an advanced skill. As we learn to tell stories, we absorb the influences around us. Certain aspects of storytelling come easier than others.

Let’s take a look at a storyteller in early development. If you look closely at the stories of kids who’ve been exposed to a lot of story, it’s surprising how much they already know.

It’s not easy teaching kids how to write a story, but the writers have got a print-out of this blog post. They don’t use it as they’re writing, but if they get stuck, I point them in that direction and their plot problems are rapidly resolved.

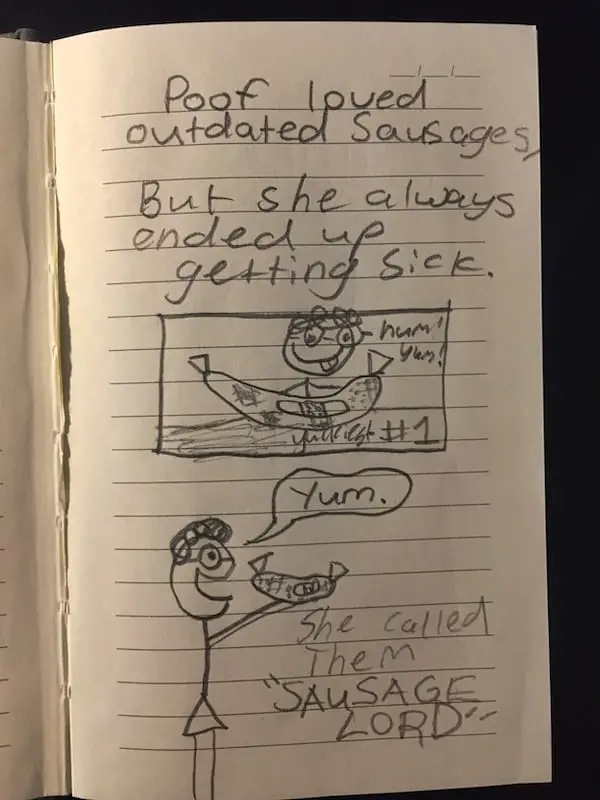

POOF AND THE OUTDATED SAUSAGES

The young creators quickly established their own ‘rules of story’, and in line with Courage The Cowardly Dog, whoever dies or changes form in one story has to revert to their original form by the beginning of the next.

Another rule is that the mode of death must be comical.

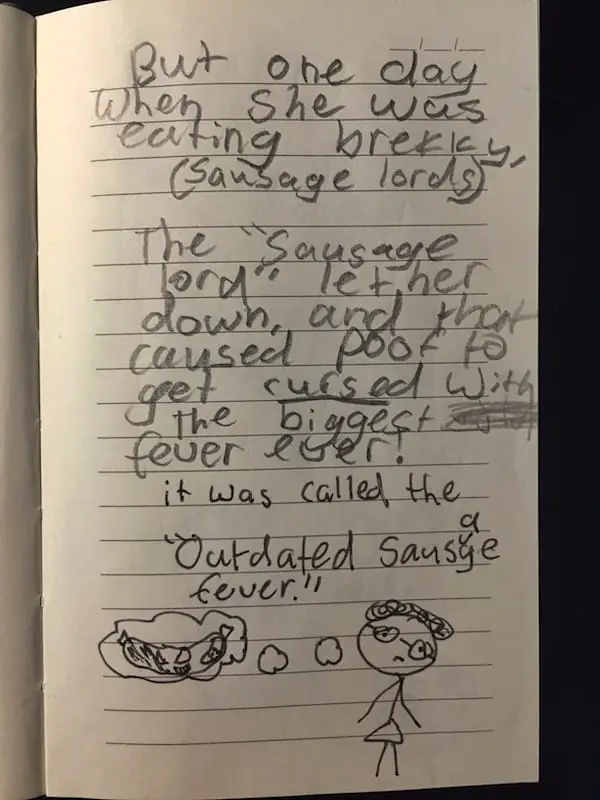

In the Poof setting, eating outdated food is a common way to die. The authors understand the inherent comic value of sausages. Bananas work in much the same way.

Poof, as a character, has unexpected, and therefore comical, likes and dislikes. The authors have started this particular story in iterative mode, by describing Poof briefly and what she ‘always’ likes to do.

The sausage has been drawn with a Band-aid on it, because this is how the ten-year-old illustrator imagines an outdated sausage would look. Or, Poof thinks she can ‘fix’ the outdatedness of it by literally slapping a Band-aid on it. The illustrator is also making use of exaggerated size for comic effect.

As you can also see, Poof is an old lady archetype, with curly hair and glasses. Later, Poof acquires underarm hair, but the illustrator has yet to achieve character consistency and often forgets to draw it in. The pit hair is therefore random, a bit like the holes in Courage the Cowardly Dog’s teeth.

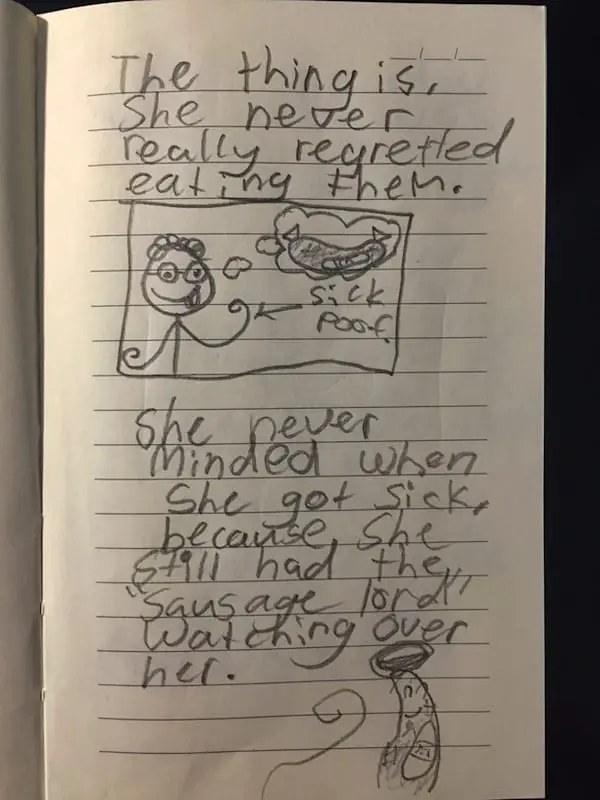

The narrator makes use of conversational narration, reminiscent of Wimpy Kid. “The thing is…”

The reader is encouraged not to buy into Poof’s fantasy of calling her fever inducing foods ‘Lord’. The speech marks around “Sausage Lord” indicate that.

By this point in the story the young writer has introduced a main character (Poof), her Shortcoming (a love for food which makes her sick, and a delusional fantasy about them) and an Opponent, the sausage, which has been somewhat personified.

Now the authors switch to the singulative (from iterative). This is the perfect place to do it.

Poof has been living on the edge, and now she has food poisoning, after a lengthy period of being okay. This is a classic story set up — a character does the same thing every day, but one day their life is shaken up. They must therefore change to cope with their new situation.

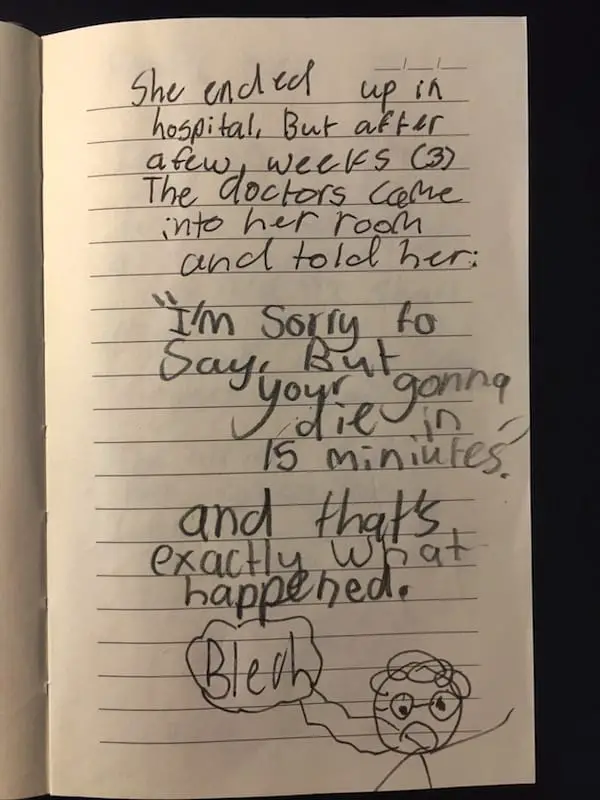

The boring details of how she got to hospital are skipped over. I believe there’s some unintentional comedy with ‘after a few weeks (3)’, which reads as if the time is the main thing, when it’s actually the sickness.

Then again, maybe it’s intentionally humorous, because the time humour continues, with the doctor saying a very non-doctor-like thing.

The writer has made comic use of a tall tale convention, or rather a shaggy dog tale convention. A shaggy dog tale is similar to a tall tale. The aim is to keep the listener interested, then end abruptly with no real climax. The listener will be disappointed and the teller will take delight in having strung them along.

Poof and the Outdated Sausages works as a story, though I did find myself wanting to know more about the Sausage Lord. As an opponent, this could have been extremely interesting. How exactly has Sausage Lord helped her out in the past? In Poof’s imagination, at least, he switches from an ally to an opponent, which is always an interesting turn of events in story.

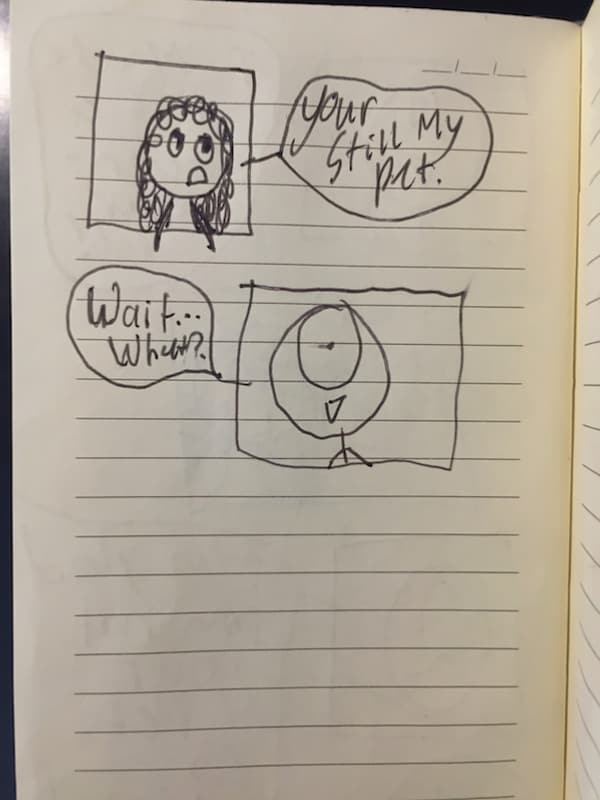

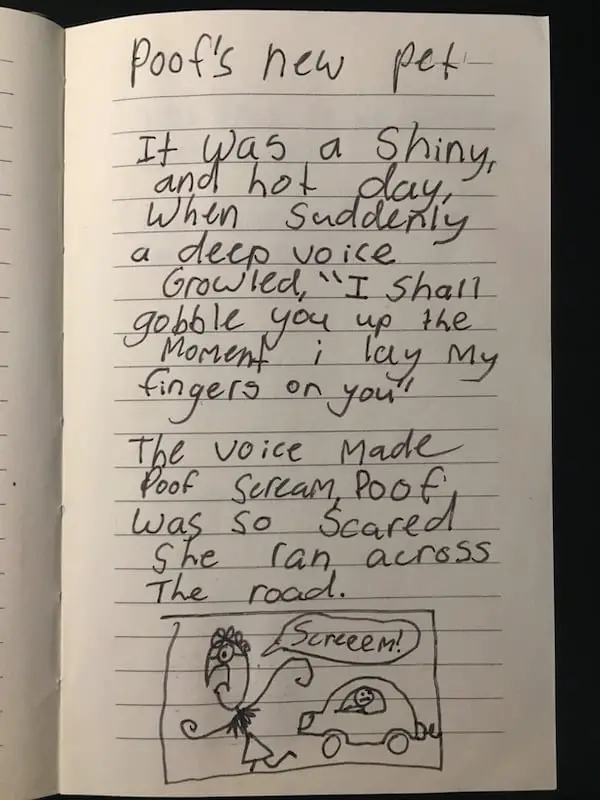

POOF’S NEW PET

An adult writer might choose ‘shiny’ for symbolic reasons but I believe this young writer has chosen shiny because that’s how it feels to her. It’s an example of transferred epithet — it’s not the day that’s shiny, but rather than everything looks shiny, because of the strong sunlight beating down on it. In any case, I think it’s great.

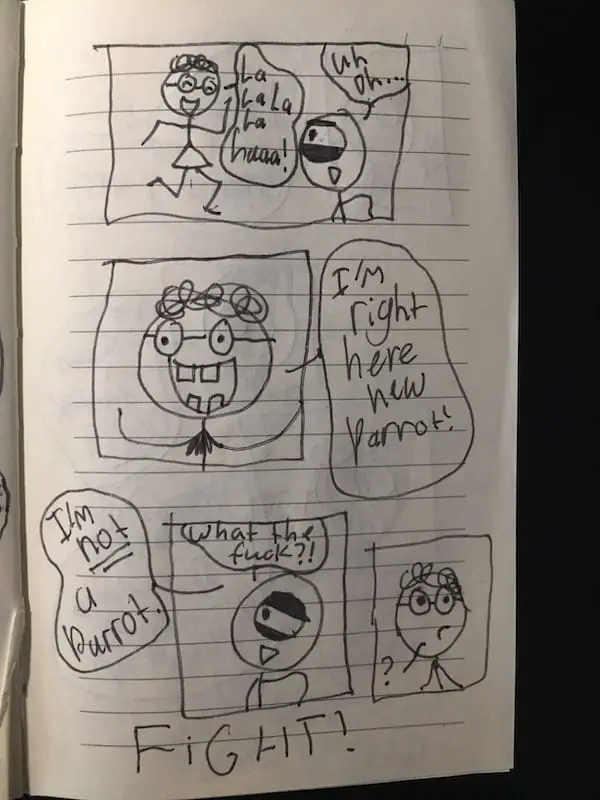

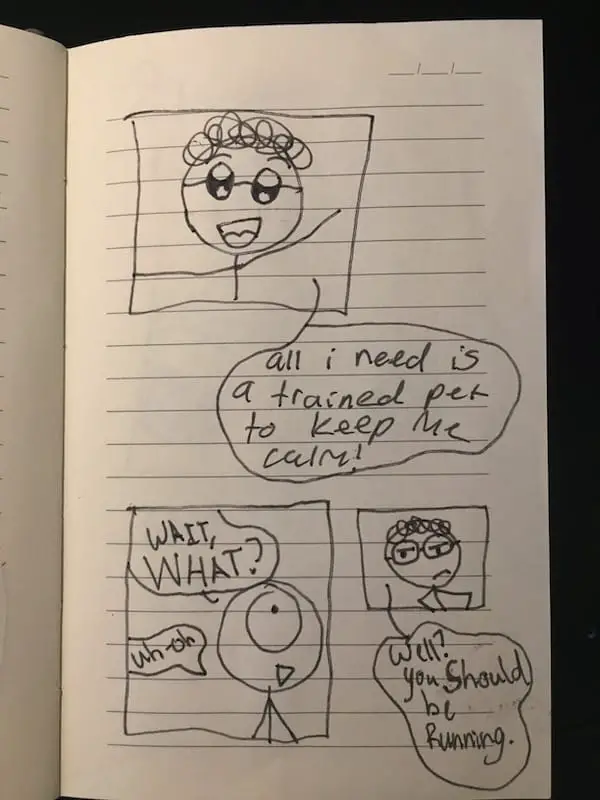

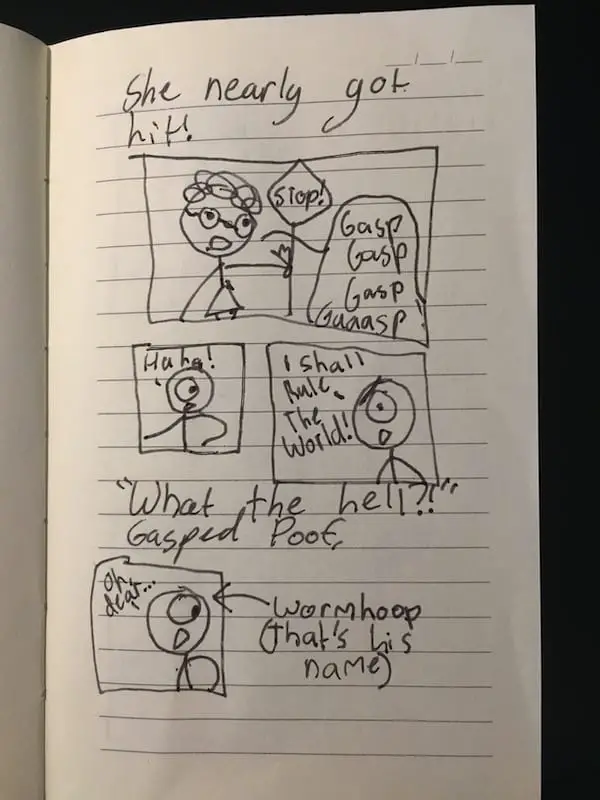

The opponent is introduced right away, even before the main character is introduced. But because this is the second microfiction in a collection, and also because of the title, the reader can deduce that the main character is Poof.

Poof’s reactions are always beautiful to watch. They are over-the-top. As in every New York thriller, at some point the main character must run through traffic. This adds to the suspense.

Notice that in this one, Poof has hairy armpits.

Telling us that she nearly got hit (exclamation mark) is over-egging the pudding somewhat, but I’ll accept it.

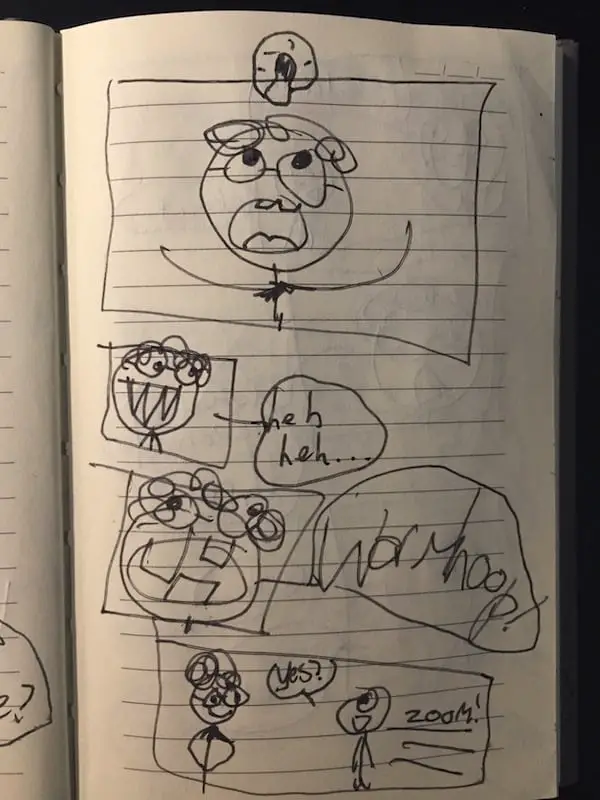

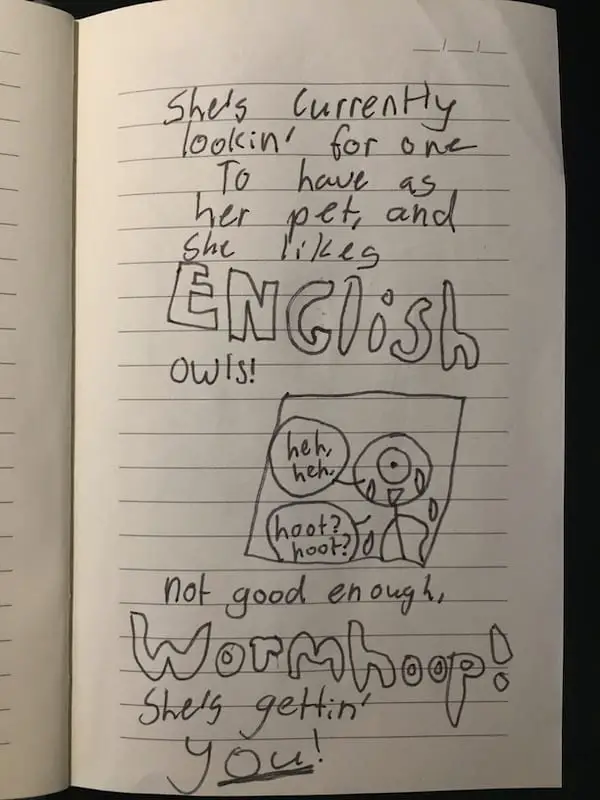

Now we see the opponent. This is Worm-Hoop the one-eyed owl, though he’s not yet named. He is introduced very succinctly: We immediately know he is power hungry and that he desires to rule the world. He is an arch-villain.

The writer isn’t quite sure how to introduce him naturally.

The author has intuited that the main character requires both a ‘need’ and a ‘want’ and has incorporated them into one thing: The desire for a pet, and the need for something to keep herself calm.

Suddenly the opposition/hero status is flipped, and Poof becomes the predator. This is another rule of the setting: Poof and Worm-Hoop are evenly matched, like Roald Dahl’s creations in The Twits.

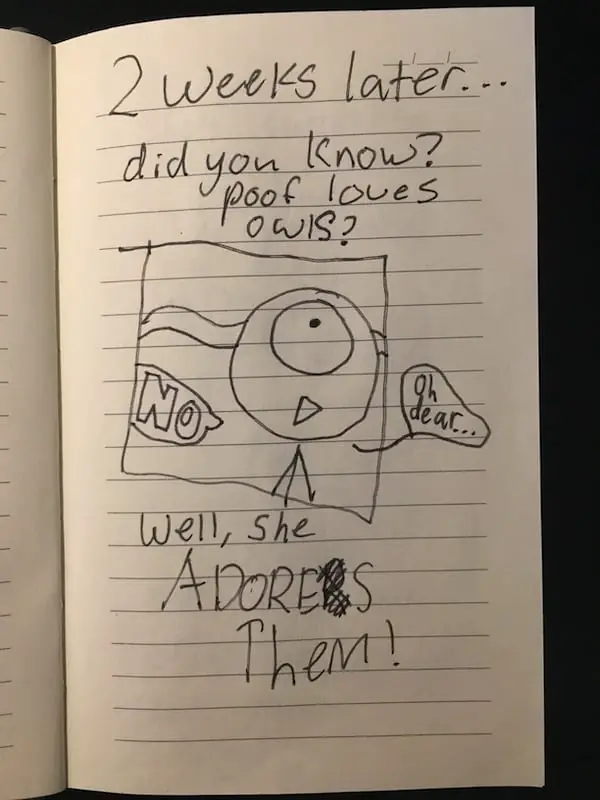

I can’t understand the reason for the ‘2 weeks later’ insertion. Perhaps they argue for a very long time.

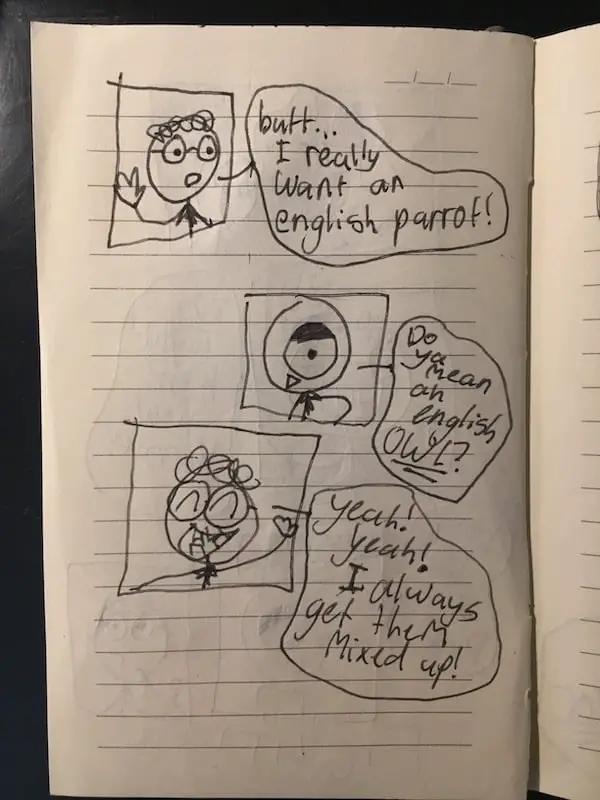

Worm-Hoop, we deduce, is an English Owl, but pretends to be a different kind of owl so that Poof won’t claim him for her pet, though this is slightly ambiguous in the text. It helps to know that the creator’s favourite type of owl is the English Owl.

I do like the character design of Worm-Hoop. Owls have eyes one on each side of the head, but this is hard to draw in a cartoon. In order to anthropomorphise him by putting his expression on the front of the face, he has been given one eye in total, because you only really see one of an owl’s eyes at once. This also gives him a unique look. His beak functions equally as his mouth. Which is it? It doesn’t matter. Worm-Hoop also sweats like a human.

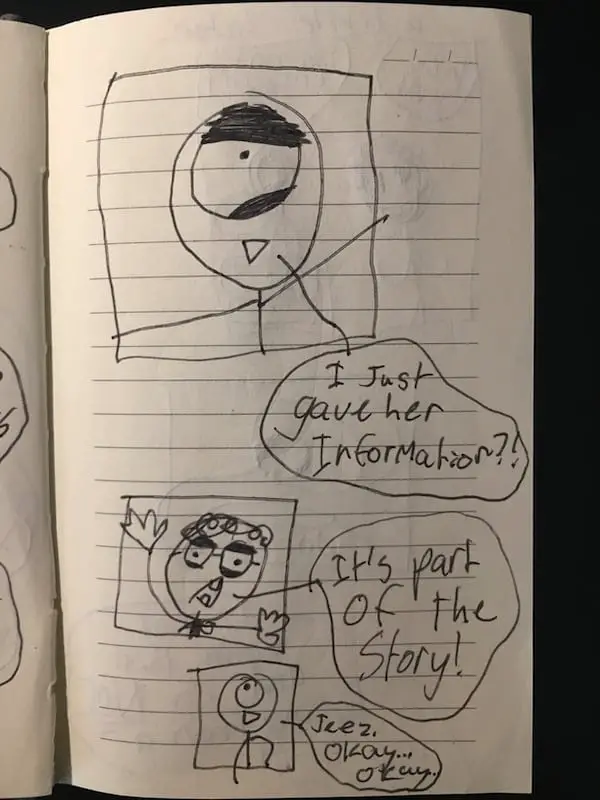

The narrator talks directly to one of the characters, breaking the fourth wall somewhat.

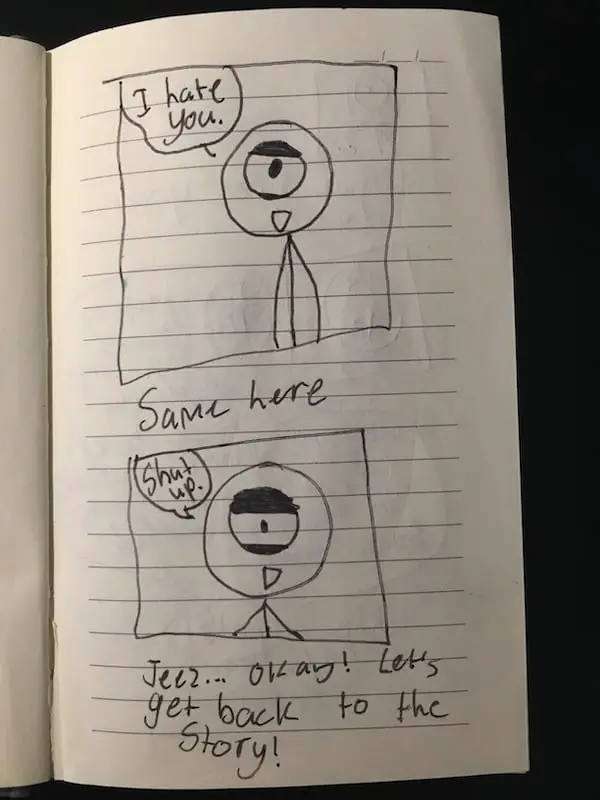

The metafictional insert ends after a minor conflict between character and unseen narrator. Sometimes these arguments go on for too long before the young writer brings the reader back into the main story. This one is a single page, so not too intrusive.

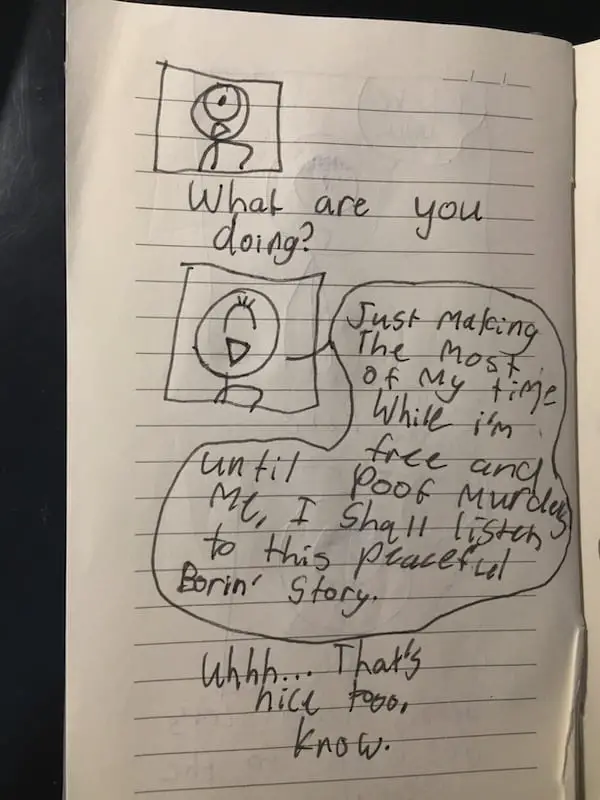

However, Worm-Hoop still appears to be talking to the unseen narrator, who seems to take the part of the reader rather than as someone who knows things the reader does not. Here, the narrator asks the character, “What are you doing?” The narrator knows no more than the reader does.

Worm-Hoop pops out of the story again, which is why the murder plot works — the reader is constantly reminded that this is just a story and no one actually dies. I suspect this narrative choice is the writer comforting herself.

The next part of the long-running gag is that Poof keeps calling her new owl a ‘parrot’, which is insulting because he is not. However, it’s natural she’d think so, since parrots can talk, and owls normally can’t.

When kids write their own stories for themselves, they get to use taboo language which they never see in their library reading material.

Worm-Hoop is so offended at this mistake that he accidentally dobs himself in as her perfect pet. If he’d only kept his beak shut, he’d have been safe and free. That is at the heart of the joke, though none of this is explained. If an adult had written this gag for a child audience, I’m quite certain they’d have explained it a bit more, but because the reader and writer are one and the same, the joke remains elliptical. Any outsider must work a little to get it.

More meta-intrusion:

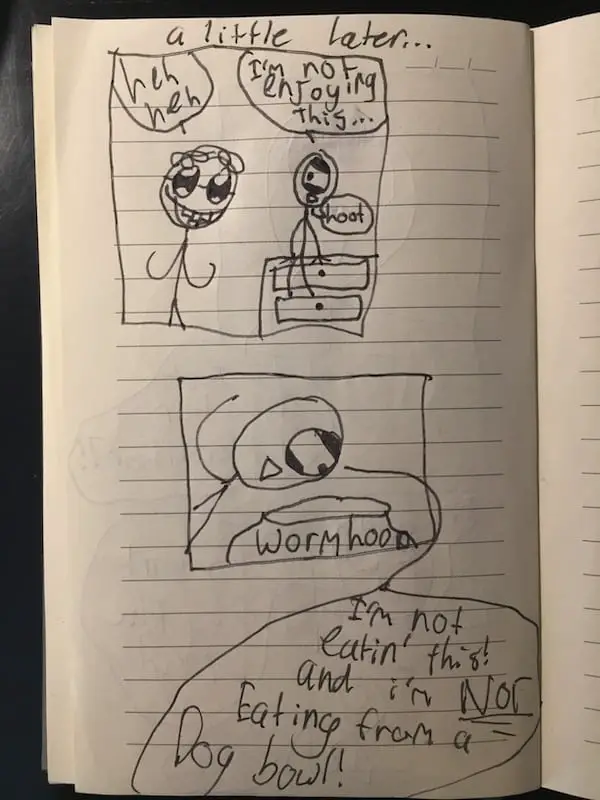

Fast forward ‘a little later’ and these two now live together. The writer knows that in order for conflict to work, they must inhabit the same space, thrown together against their will. (Or, against at least one character’s will.)

It seems Worm-Hoop sometimes hoots as well as speaks English. Instead of perched on a branch, he’s perched on a chest of drawers.

He’s got his own bowl, but it’s a dog bowl.

And that’s the end of that story, which feels more like the end of a chapter. And it is. The young writer doesn’t make much distinction between stories and chapters. Some chapters are entire stories in themselves; others require several chapters.

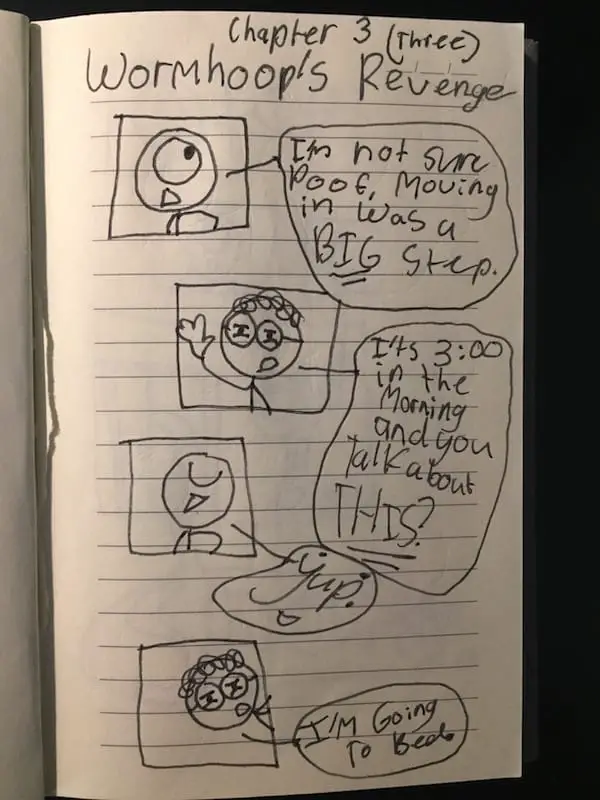

WORMHOOP’S REVENGE

The gag in this spread derives from adult relationships, and the fact that in relationships, couples don’t always feel the same way about each other at exactly the same time.

I figure this has been absorbed from watching TV.

This chapter is more like two sequential gags than a complete story, because each follows the rule of comedy rather than the rules of story.

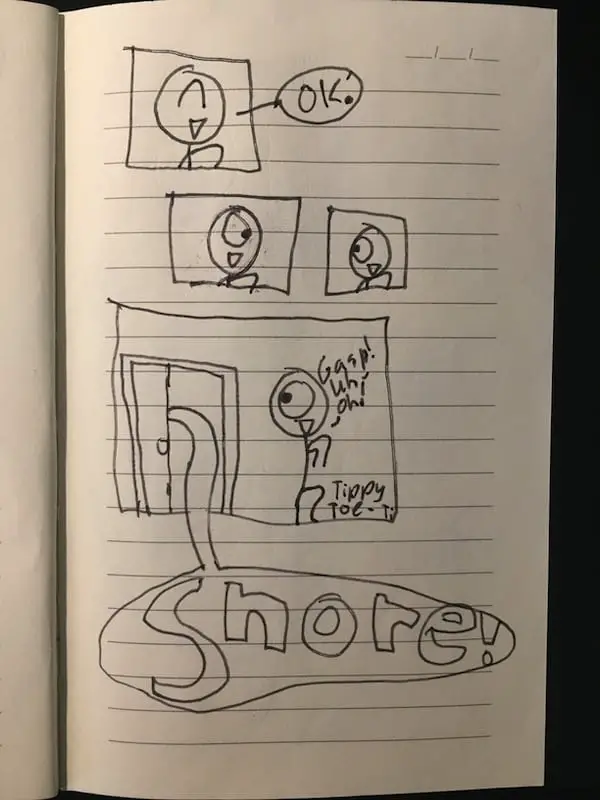

In the second gag, Worm-Hoop is terrified of Poof’s gigantic snoring, which juxtaposes comically with tippy-toeing by her room so as not to wake her. (How does she not wake her own self?)

Interestingly, two separate depictions of Worm-Hoop suggest he is looking at himself, sharing the uncomfortable feelings with himself. This works nicely for an owl, because of the two eyes on each side of the head, which I think the illustrator has really made the most of.

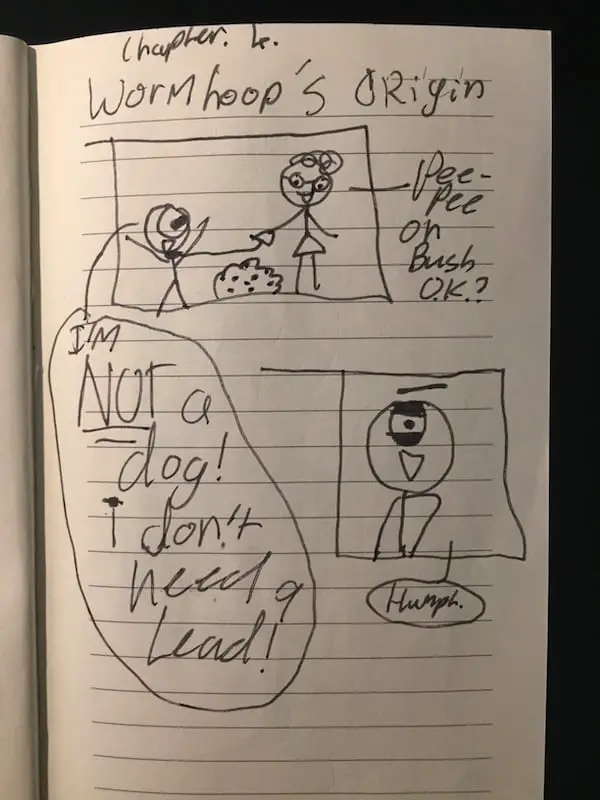

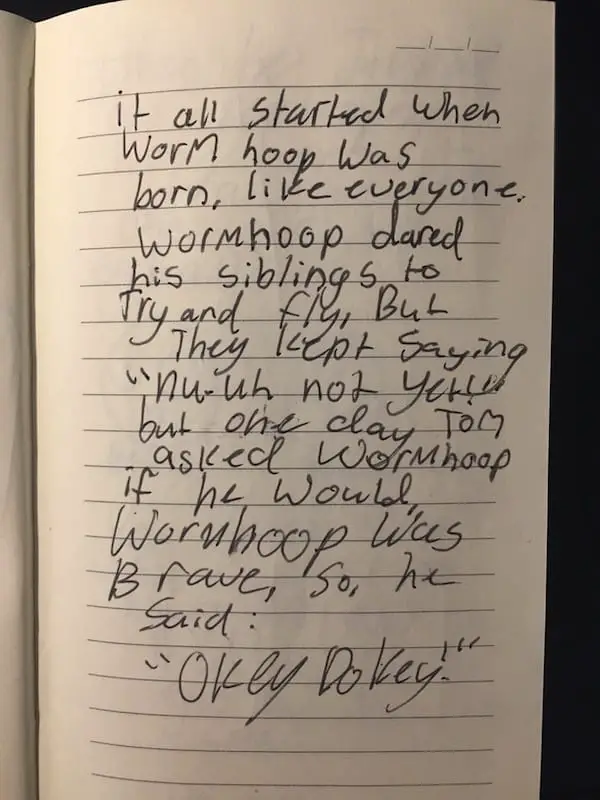

WORM-HOOP’S ORIGIN STORY

The writer knows that the reader won’t care about a character’s backstory until we’ve had a bit of action and started to wonder. This young writer is a big fan of super heroes, so is familiar with the concept of origin story.

The gag in which Poof treats her pet bird like a dog continues. I believe the writer has been inspired by stories such as The Pigeon Wants A Puppy by Mo Willems, in which one character completely misunderstands the nature of some other character, with disastrous results.

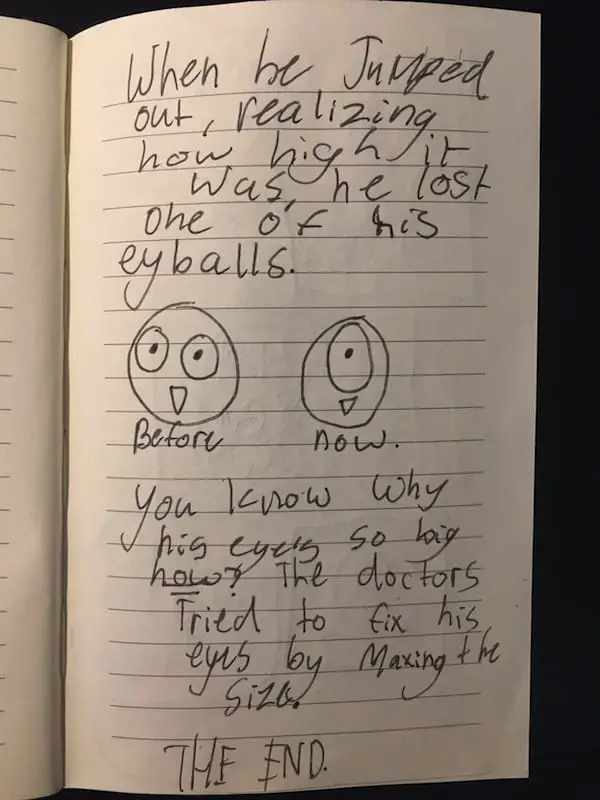

This amuses me because it’s almost a satire of all those picture books in which a baby bird/elephant/dolphin goes out into the world for the first time, by doing something scary.

Unlike your typical cute baby animal character, Worm-Hoop is gripped by unexpected bravado. Picture books don’t tend to exist for those characters, who don’t tend to require the ‘Be Brave’ books in the first place! However, these foolhardy tropes are great for comical stories like this.

A rule of thumb for illustrators is, you don’t need to illustrate what’s clearly been said in words, but breaking that rule works to great comic effect right here.

The illustrator must have realised one eye took up about the same amount of real estate on his face, and offered a comical explanation for that, too.

I think this chapter works as a series of comic gags. If an adult were writing this for children, they’d have depicted Worm-Hoop’s siblings, making him distinct from the others, Ugly Duckling style. They’d probably also have shown the doctor, and made more of that scene.

E.g. “Hey doc, can you fix my eye? It fell out when I got a surprise.”

“No can do. You lost it forever. But I’ll max the size of the other one, and then you’ll be good as new.”

“Okay.”

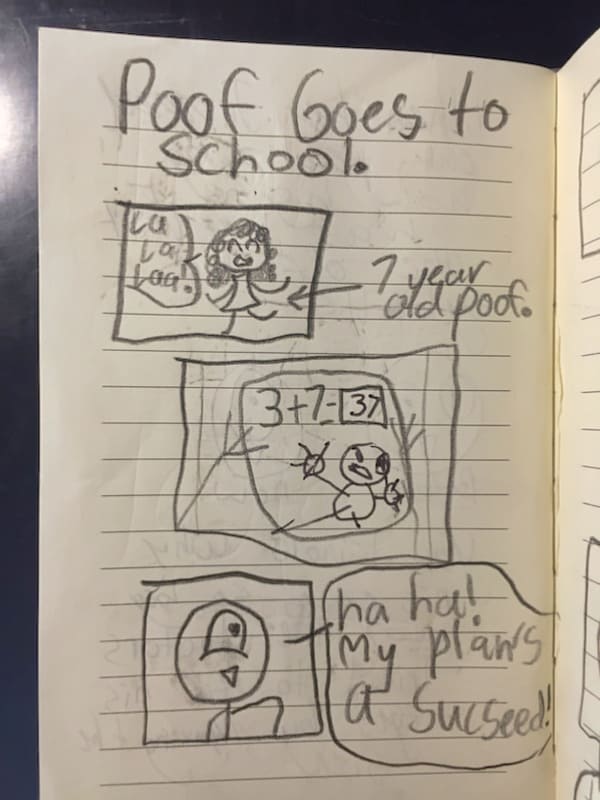

POOF GOES TO SCHOOL

Now we have a satire on all the ‘First Day At School’ stories, and Poof’s backstory. I believe this was inspired by the “Little Muriel” episode of Courage The Cowardly Dog.

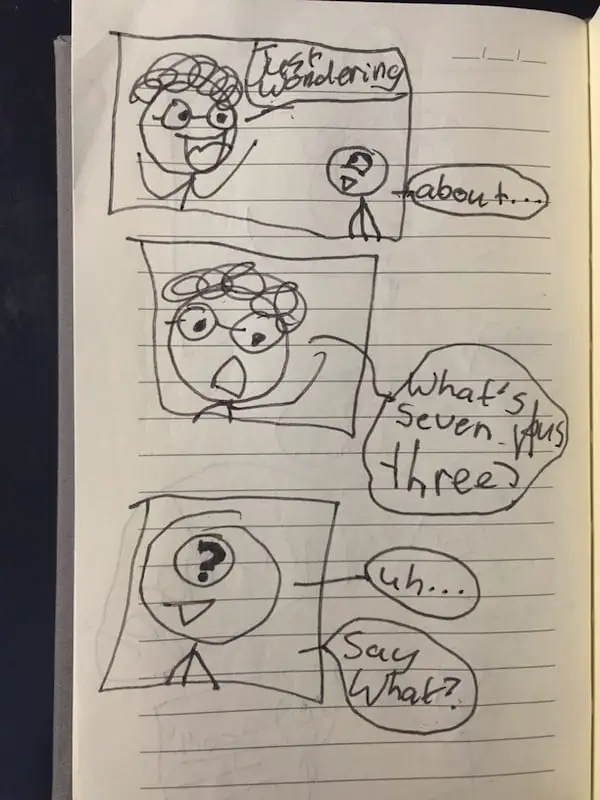

The first gag is that she doesn’t know how numbers work. I’m quite sure this is a gag taken from somewhere else (but I wouldn’t know from where).

Little Poof has drawn herself in a childlike way, which is quite an achievement, since the child drawing the rest of the illustrations is a child, and therefore also, quite naturally, drawing in a childlike way.

Then Worm-Hoop pops in. We don’t know what just happened yet.

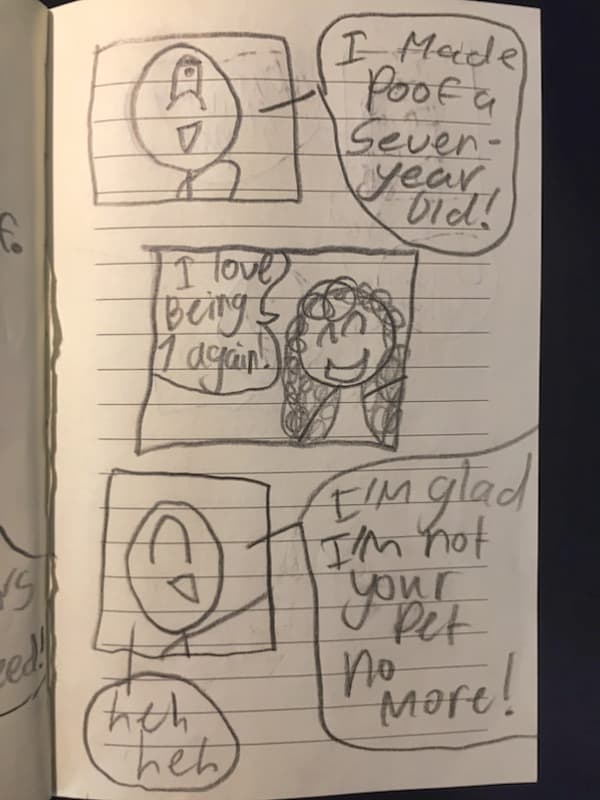

The big reveal: This isn’t a flashback at all. Second reveal: Poof LIKES being seven again. Third reveal: Worm-Hoop did this so he wouldn’t have to be Poof’s pet anymore. Though this writer doesn’t know what ‘reveal’ means, she has a good grasp of the technique.

The comedown is that making Poof younger doesn’t turn back time. It simply makes her younger.

I believe an adult writer would have explained this more thoroughly. And would have possibly left the reader with more of an ending. The writer has included a Battle and a revelation (not a Anagnorisis, because these comic characters never change), but she leaves off the New Situation. However, we can deduce what that is. They continue to live together, only now Worm-Hoop has the antics of a seven-year-old to contend with. Ideally, this chapter would have ended with a comic scene showing that. For instance, Poof uses him as a non-consenting cuddly toy when she takes him to bed.

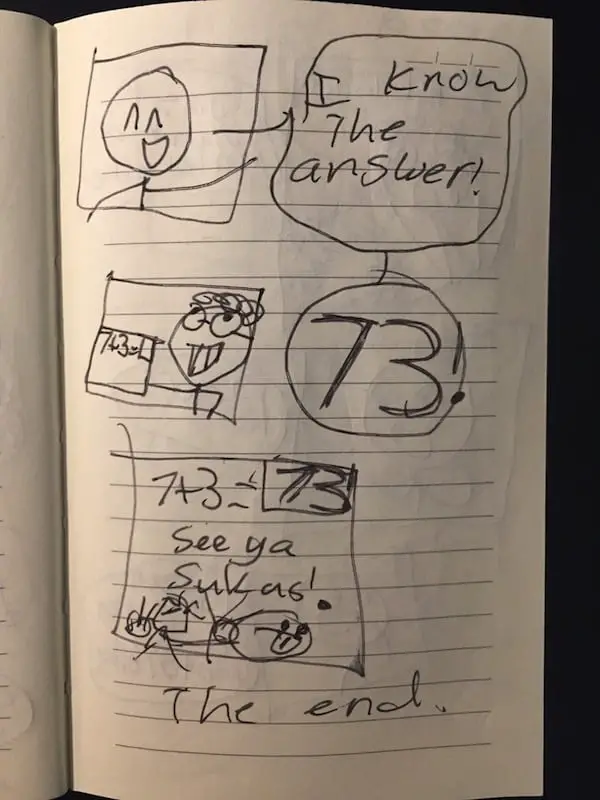

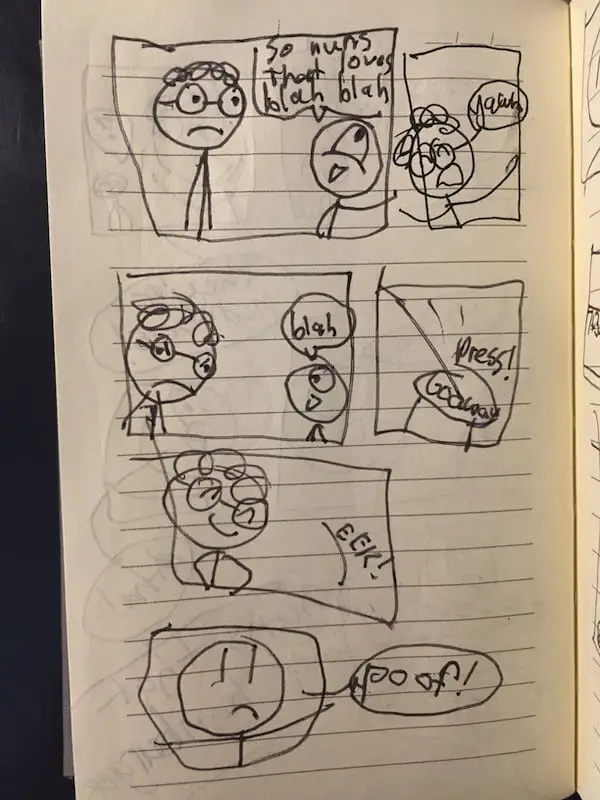

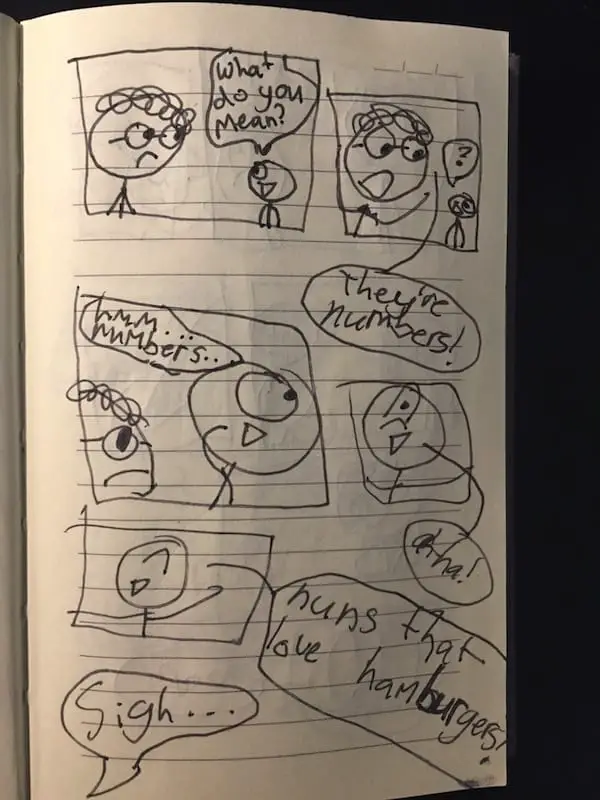

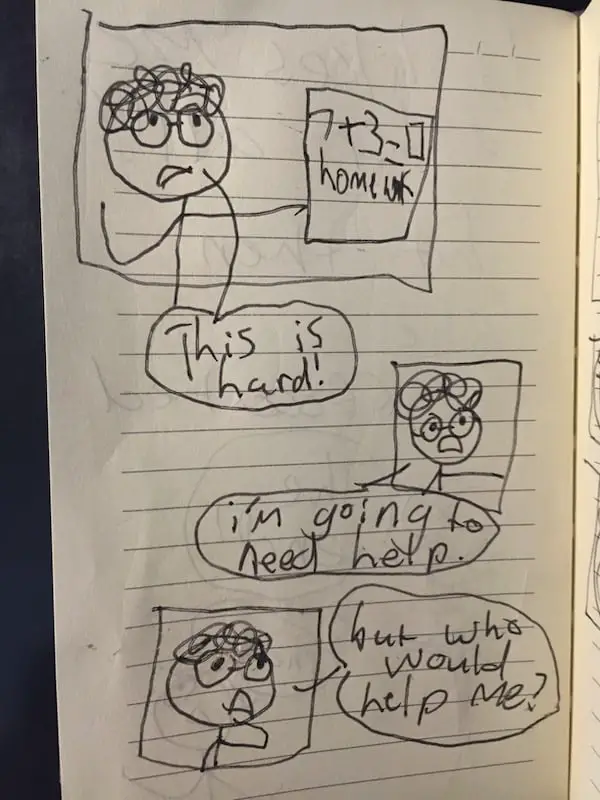

POOF’S MATHS PROBLEM

Poof has poofed back into her usual form as an old lady, but the writer has decided to keep with the maths theme. Even when she looks like an old lady, it is now clear to me that Poof is basically a naughty, mischievous seven-year-old in an old lady’s body.

Poof’s shortcoming (she’s bad at maths) and her desire (she wants to do her homework) are introduced succinctly on the first page.

The illustrator has absorbed comic book conventions after reading lots of comics. (E.g. the lightbulb for a good idea.) The reader knew Poof would think of Worm-Hoop. (The writer is making use of audience superior dramatic irony.)

Her Plan is to call for him. He comes immediately.

The illustrator has decided to use Worm-Hoop’s eye as a window into his brain. The eye can contain all sorts of symbols, and in this case, a question-mark.

The gag is that Worm-Hoop knows even less than Poof does. Poof doesn’t know how to add, but Worm-Hoop doesn’t know the meaning of ‘number’.

He therefore delivers a nonsensical response, and that is the gag.

I expected the story to end there. It works as a complete gag. But the young writer has decided (subconsciously, of course) to turn this into more of a narrative than a simple set-up and payoff, so next we have a Battle sequence in which Worm-Hoop struggles (with himself) to understand the problem. (I asked the illustrator and she tells me that button belongs to a calculator, but I don’t think that’s sufficiently clear without author intervention. The machine which doesn’t work as characters expect it to is a classic Spongebob gag.)

The gag from a previous chapter is reused. I’m not sure who the characters are in the final box. I think the illustrator is getting tired by this stage.