“Poison” is a short story by Roald Dahl. Find it in Someone Like You, first published in 1953. A man discovers a poisonous snake asleep in his bed.

In 2023 this story was released as a short film adaptation directed by Wes Anderson. In adapting “The Ratcatcher” and “The Swan” for screen, I wondered how Anderson would deal with the uncomfortable racism in this one. Would he leave it on the screen, just as it appeared on the page? Let’s see how Wes dealt with that.

First, we need to talk about snakes in general.

HOW DANGEROUS ARE SNAKES?

SNAKES IN AUSTRALIA

I’ve lived in Australia for almost 17 years and have not yet seen a snake in the wild. But if you meet an Aussie on an overseas bus tour, they’ll likely confirm your notion that Australia is teeming with deadly wildlife, and only a born-and-bred Australian is tough enough and savvy enough to deal with such peril. Visitors beware.

In reality, most Australians I know have rarely encountered. Those who have remember it like the moment they heard about 9/11. One friend was hanging out the washing when a brown snake slithered by… My mother-in-law was running barefoot across a meadow when she trod on a brown snake… A guy down at tennis took a picture when his puppy carried a small snake inside and dumped it as an offering.

Snake encounters are what you might call ‘photo-worthy moments’, even in regional Australia.

My closest encounter: I found a shed snake skin in the wood shed, which did not endear me to that wood shed because I happen to live in the part of Australia which has the most deadly snakes in Australia. I also find lizards look a lot like snakes when running through long grass. To keep us on our toes, there is also such a thing as a ‘legless lizard’.

So I attended the Snake Training And Sausages event held down at the local fire station. The seminar was presented by our local snake catcher. If you find a snake on your property you’re not actually allowed to maim or kill them. You must call a snake catcher. The snake is returned to the wild.

Every snake catcher I’ve ever met (okay, that makes two) looks like a brother or cousin of Steve Irwin. This guy wore a sparkly stud in one ear and reassured his captivated audience that snakes are stupid. If a snake is slithering towards you, they really don’t mean to be. Stamp your feet, vibrate the ground and it should change direction. Also, most people get bitten on the hand, not the foot. They’re reaching into a nook or a cranny where a frightened snake happens to be. Snakes won’t come for you. They are not predatory or vindictive. Still, while out in the yard, best to wear boots and jeans. Yes, even in the heat of summer.

Rural Australians are advised to keep a snake bandage in their medicine cupboard. If you’re doing yard work, you’re supposed to keep it on you, in a bum bag or similar I guess. Also a mobile phone, because if you get bit, you’re supposed to STAY ABSOLUTELY STILL.

I don’t know a single Australian who does yard work while wearing a bum bag with a snake bandage in it. I do know Australians who will happily use a whipper snipper while wearing thongs. (That’s ‘flip-flops’ or ‘jandals’, for clarification.)

Just in case, I purchased one of the snake catcher’s snake bandages for ten bucks, watched carefully how to put one on (honestly I’ve now forgotten, here’s a YouTube refresher), and made a mental note: If or when I get bitten, DON’T PANIC.

Actually, Douglas Adams was right. You might need that towel:

If you see a snake inside your home, get all people and pets out of the room immediately. Shut the door and fill the gap underneath with a towel, then call a professional snake catcher for assistance.

What to do if you see a snake in the wild

Humans are more dangerous than animals, no mistake.

Cook, Hodes, and Lang (1986) study used loud noises to condition people to fear the sight of snakes and guns. They found that people acquired a fear of the snakes much more easily even though the noises matched the sound made by guns. Most people pay more attention to animals than to other people. Study from New of Barnard College in New York, says, “our brains keeps monitoring a living creature probably because, unlike, a bridge or a building, a person or animal can suddenly turn from friendly to hostile.

The Aesthetics and Psychology Behind Horror Films

PANICKING

You’re not supposed to panic because panicking increases the blood flow which sends the venom straight to the heart.

Of course, advice to NOT PANIC AND LIE COMPLETELY STILL is — hilariously — easier said than done. How does one NOT PANIC when one has just been bitten by the second most deadly snake in the world? That would be the Eastern brown snake, by the way, in case you were wondering.

THE HERMENEUTICAL MYSTERY AROUND SNAKES

To make matters worse for Australians who think they might have been bitten by a brown snake:

- Brown snakes aren’t always brown. They can be near black to light tan, chestnut or burnt-orange. They’re easier to identify if you can see its belly, but a snake cannot be trained to play dead and roll over on command.

- Many Australian snakes are brown, not just the Brown snakes. You could be dealing with a killer, or nothing more dangerous than an earthworm.

- Even if they bite you, they don’t always release venom. (Called ‘dry bites’.)

- That said, a small-sized snake can release the most deadly amount of venom. You simply can’t tell by looking at the snake how dead you’re about to get.

- A snake bite doesn’t necessarily feel like anything much. It doesn’t hurt. So you may not realise immediately that you’ve been bitten. Were you bitten or weren’t you? WHO KNOWS. (Australia is fortunate not to have necrotizing snakes like pythons, but the consequence of a gentle wee lick is not knowing for sure what just happened, if anything.)

- Panicking can itself kill you. An Australian died last month after an encounter with a snake. Autopsy revealed no venom in his body. The man had died from a heart attack, not from a venomous snake bite. Vale Donny Morrison from Queensland, who died trying to remove a brown snake which had coiled itself around a mate’s leg at their high school reunion.

Roald Dahl makes the most of this aspect of snakes: You can never be entirely sure about a snake — its exact variety, if it bit you, how much venom you got… or if it was ever really there.

The legend around snakes shapes our reality. And via this well-crafted tall-tale with its somewhat shaggy dog ending, Dahl contributes to the legend.

SNAKES IN THE BED: IT’S A THING

The krait snake in Roald Dahl’s short story is tiny.

Wes Anderson’s film shows just how tiny it is — more like a very hungry caterpillar than like an Australian Brown snake, which can grow up to 2.4 metres long. That’s 7.8 feet. Until I realised the tiny size of this snake, it baffled me a bit that someone could be unsure if a snake were in his bed or not. A snake of 2.4 metres does not simply slither unnoticed into the bed.

It is absolutely true and well-known in Australia that snakes will cuddle up to you if you’re camping out on a coldish night. Being reptiles, they are drawn to your body heat. Australian swags come with zippers and campers are advised to use them. (Not only that, any openings in your tent will offer you as sacrificial mosquito meat.) Still, we’ve all heard stories about such-and-such’s mother’s brother’s uncle who went camping, fell asleep drunk and woke up with a snake in his sleeping bag.

Tomorrow When The War Began is a famous young adult novel by John Marsden, later adapted for film. Chapter four features the Snake in Kevin’s Sleeping Bag. Alongside Blowing Up The Bridge, the Snake in the Sleeping Bag scene is, for me, the most resonant:

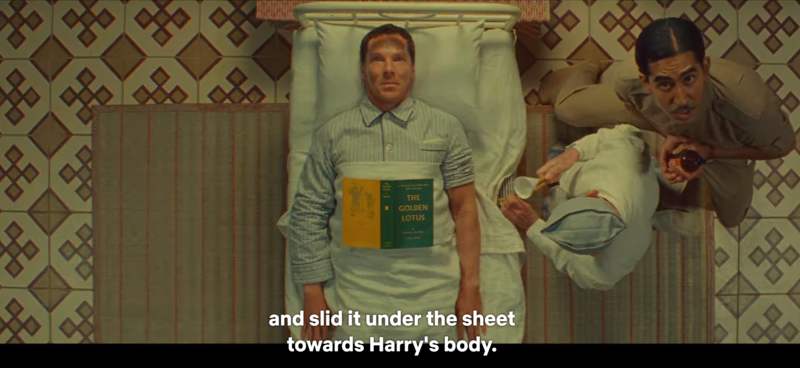

HARRY’S READING MATERIAL: THE GOLDEN LOTUS

In Dahl’s short story, Timber Woods checks on his housemate to see if he’s fallen asleep reading. We deduce he checks on the other man to see if he should turn off the light. The book itself is irrelevant after its McGuffin purpose, but Wes Anderson has chosen to include it. Not only that, viewers are given a clear view of the book’s title. Harry Pope has been reading The Golden Lotus.

So what is the significance to this story? Why did Anderson choose this book in particular?

The Golden Lotus is an English translation of an infamously popular Chinese book written in the 1500s. Written under pseudonym, the book contains some steamy passages. Think Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The book has been officially banned for most of the time since initial publication.

In truth, this is a massive book of 100 chapters and the sexy parts comprise just 3% of the total. (Yes, people have done a count up.) Despite its banning — or because of it — the comedy of manners has always been popular among the educated classes, who would read it secretly.

It makes sense that a white man in Bengal might be reading such a book. Adding to the comedy of the scene, Harry was probably trying to read it in private but a snake put paid to that.

Which part of the book was he up to? Had he, by chance, been reading the 3%? Roald Dahl managed to write a bedroom scene about pyjamas, pyjama openings, a hose, three men and a snake, yet none of this reads in the slightest bit like sexual innuendo. Even when the sheet is pulled back, Woods focuses on the fancy button which fastens Harry’s pyjamas. There is no suggestion of homoerotics in this story at all. (I wonder if Dahl was making sure of this by having Woods mention the button, when Woods could have easily been looking at something else.)

By having Harry read a slightly sexy book, the narrative becomes just a little bit sexualised, but only in the sense that a man may have been caught doing something he wished to keep private. Alternatively, he has mistaken his own appendage for a snake when it moved in a way he did not expect.

HOW DOES WES ANDERSON AMELIORATE THE RACISM?

There’s a place for showing in literature the extent of 20th century racism on the part of white men who colonised places such as Dar Es Salaam (in Tanzania) and Bengal. But white writers and film-makers are not obliged to depict casual racism of yore wantonly and without thought. Decisions to retain it depend partly on the function of the story. The function of a tall story like this is — chiefly — to entertain. So why alienate viewers of colour?

Here’s the paradox. Writers and film-makers who take the racist parts out then open themselves up to accusations of rewriting history and invisibilising the very real systemic racism which continues to this day. Showing the more blatant forms of historical racism opens white people’s eyes to contemporary forms. So we shouldn’t rid the world of it entirely.

Wes Anderson has made some very judicious decisions. Here’s what he did:

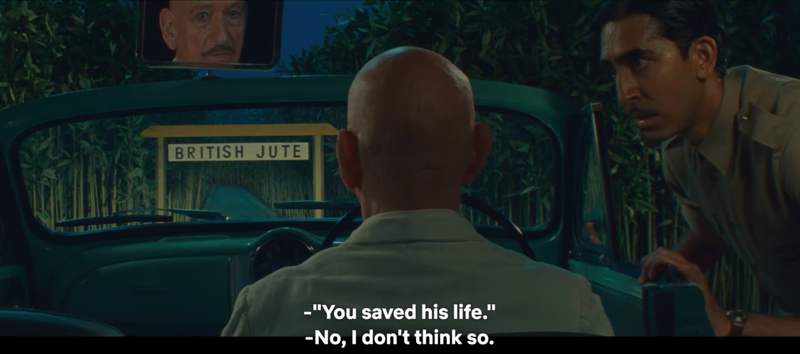

- First, the viewpoint character is acted by a man of colour, Dev Patel, who plays Timber Woods. (I take it “Timber” is the nickname.) Whatever the man’s real given name, Dahl’s viewpoint character is white coded. The author explained on record that Branch is named after a comrade who was killed during the war. (Wes Anderson includes this information in the credits.)

- The narrator in Dahl’s short story refers several times to ‘the little Indian’, which is not just a comment on the man’s height, but indicates his lack of status as a doctor of colour. Dahl himself was very tall, so almost everyone in the world was ‘little’ to him. The way Dahl uses this descriptor in the text sounds condescending, though completely in line with how white men (like Dahl himself) would have regarded a ‘native doctor’ — more like a servant than as a learned professional who has gone out of his way to make a house call in the middle of the night, and knows more about medicine than either of the white men ever will.

- The actor who plays the ‘little Indian’ is Ben Kingsley (named Krishna Bhanji at birth), whose father was a Kenyan-born medical doctor of Indian descent and whose mother was a white English woman. Kingsley speaks with a British accent. Over the years, Kingsley has played many different roles including Hamlet and Ghandi.

- Note that Wes Anderson retains the racist diatribe issued by the humiliated snake victim when the doctor asks if he might have been dreaming.

- The most cringey part of Dahl’s original short story is the ending. Even after enduring the racist diatribe, the doctor returns to his car and says to Woods, referring to the clearly racist Harry, “All he needs is a good holiday.” Wes Anderson has crafted an open ending, with ambiguous dialogue. In the short film, “Timber” Woods is far more effusive in his praise for the doctor. A modern audience will likely agree that the doctor needs thanking, so this feels more fitting than Dahl’s story, in which characters treat a doctor dismissively. Reading Dahl’s short story, it did not sit well with me that the poor doctor should be insulted, yet respond meekly that the poor white man ‘just needs a holiday’. There was so much more to the diatribe than that. Namely, racism comes to the fore when racist people experience stressors such as humiliation. Meaning, racism is always there, undergirding society. Much of the time it lies invisibly, but apply a modicum of pressure and it comes rushing out.

- As the doctor sits in his car, he faces a sign which says British Jute. This claiming of space is a stark reminder of how the British Empire has colonised many parts of the world for its own capitalist, exploitative purposes. In contrast, Dahl never explained why the two white men were in Bengal. A white British audience would simply assume the men had important business there. Question not. Dahl’s characters arrive on the page in statu nascendi (without backstory, as if they’ve just been born). Wes Anderson has acknowledged on screen that the racist diatribe did not come from nowhere, and that there is an entire system of racialized inequality surrounding the oasis of this bungalow.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Wes Anderson is not the first film-maker to adapt Dahl’s “Poison” short story. I will say that in all three cases, the actor who plays Harry does a great job of the Can’t Move In Bed scenes.

THE BBC DRAMATIZATION

You may be able to unearth the BBC dramatization of this short story somewhere e.g. on YouTube. “Poison” was broadcast July 2016.

Alfred Hitchcock Presents (an anthology TV series which ran from 1955 to 1962)

“Poison” was broadcast in 1958 as part of the fourth season and is called “Dial S for Snake”. This one is black and white. We are shown how the snake is real as it emerges from under the pillow. “Your friend needs a holiday” is changed simply to the American “Your friend needs a holiday.”

After the doctor leaves, Woods pours them both a drink and accuses Harry of imagining the snake. Harry is super cranky about this and the two men get into a fight. Woods lies down in Harry’s bed and is promptly bitten by the snake. But Harry is cranky and refuses to call the doctor back. He lets his friend die.

Alfred Hitchcock appears as narrator and tells us Harry spent some time in prison for failing to call a doctor. “Apparently the snake couldn’t keep his mouth shut.”

Hitchcock also adapted Dahl’s “The Landlady“, “Mrs. Bixby and the Colonel’s Coat“, “Man From The South”, “A Dip In The Pool”, and “Lamb To The Slaughter“.

Tales of the Unexpected (various Dahl adaptations which ran from 1979 to 1988).

“Poison” is Season 2 Episode 5 and you may be able to see it on YouTube. In this series, Roald Dahl himself introduces his stories.

Wes Anderson uses Ralph Feinnes as a slightly eccentrified Roald Dahl stand-in, and has recreated the famous garden shed where Dahl used to write. With diction and pausing reminiscent of the Queen’s Christmas speech, the actual Roald Dahl of this version tells us about the incident which inspired this story.

At the age 20 he worked for a company out in Dar Es Salaam. Looking morning he was shaving in the bathroom. He happened to glance out the window. The gardener outside was raking the gravel on the driveway down below. At that moment, Dahl saw a mamba, six feet long, moving over the gravel towards him. “Look out!” Dahl yelled. “Behind you! A snake!” Still, the mamba bit the gardener on the ankle. Dahl rushed downstairs and drove the gardener straight to hospital. They were there in ten minutes. But this wasn’t quick enough. The gardener died that day. Dahl then talks about the krait, which is equally venomous but almost more frightening because he is so tiny he can surprise you better. Perhaps this short story was Dahl’s way of processing the trauma of having seen a man killed by a snake?

Note that this adaptation is quite different again from the original short story. Timber Woods is shown picking up a white woman at a nearby bar. Meanwhile, his bachelor housemate drinks at the bungalow. A narrator tells us he ‘hates India’ and can’t wait to be sent back home.

Woods takes his blonde lover in the house and tells her to be quiet. What’s with the addition of a Princess Diana lookalike? Three suggestions for you.

- One: A man is even more humiliated when there’s a woman to witness it. Worse, she tells him he’s probably drunk again.

- Two: The addition of a woman removes homoerotic readings for a homophobic audience.

- Three: Sandra does not want Woods to call the white doctor because she isn’t supposed to be there. This lampshades the white audience wondering why a white man would want anything to do with a native doctor.

- Four: There may be some 20th century rule in which a story containing a snake must also include a helpless maiden.

Instead of calling the doctor a “dirty black…”, Harry now calls him a “failed M.D. Calcutta”. Later, in the car, he laughs off the insult after Woods apologises for Harry. “And I’m not a failed M.D.!”

Somehow, this 1980s adaptation manages to be racially worse than Dahl’s much older story, and with the addition of a very annoying woman who struggles to start a car and is at one point manhandled by (the much older) Woods for failing to calm down, also manages to insert misogyny.

The ending is also different because the snake makes a comeback. The Tales of the Unexpected Crew must have considered Dahl’s ending not quite strong enough to work on the screen.