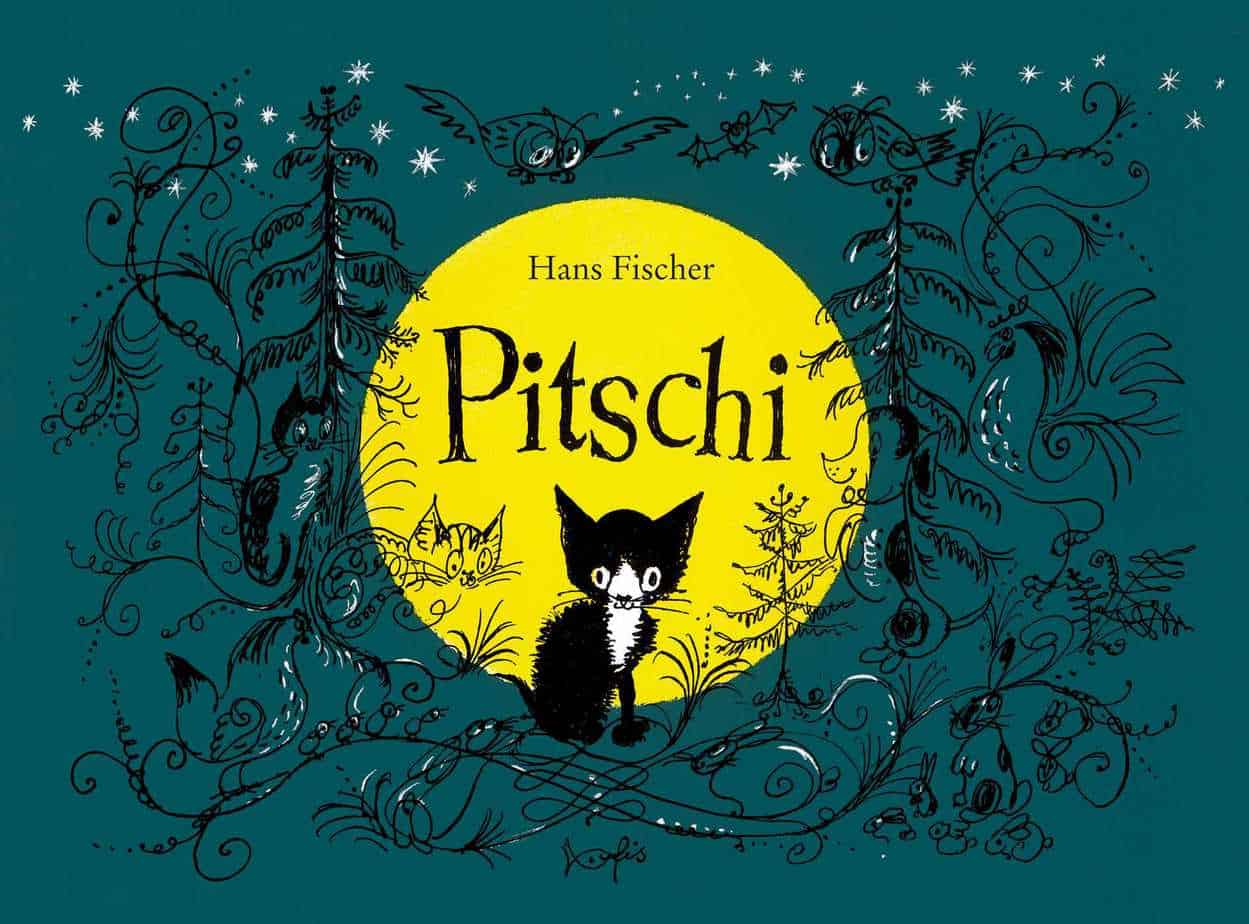

Pitschi is a picture book written and illustrated by Swiss storyteller Hans Fischer, first published in 1948. Pitschi is a good example of a post war children’s book: dangerously cosy with a stay at home message.

SETTING OF PITSCHI

- PERIOD — mid twentieth century

- DURATION — It takes place over 24 hours. The night is the scary part and is integral to the story.

- LOCATION — This is the Switzerland of yesteryear, where old cat ladies live alone in the wilderess surrounded by their farm animals.

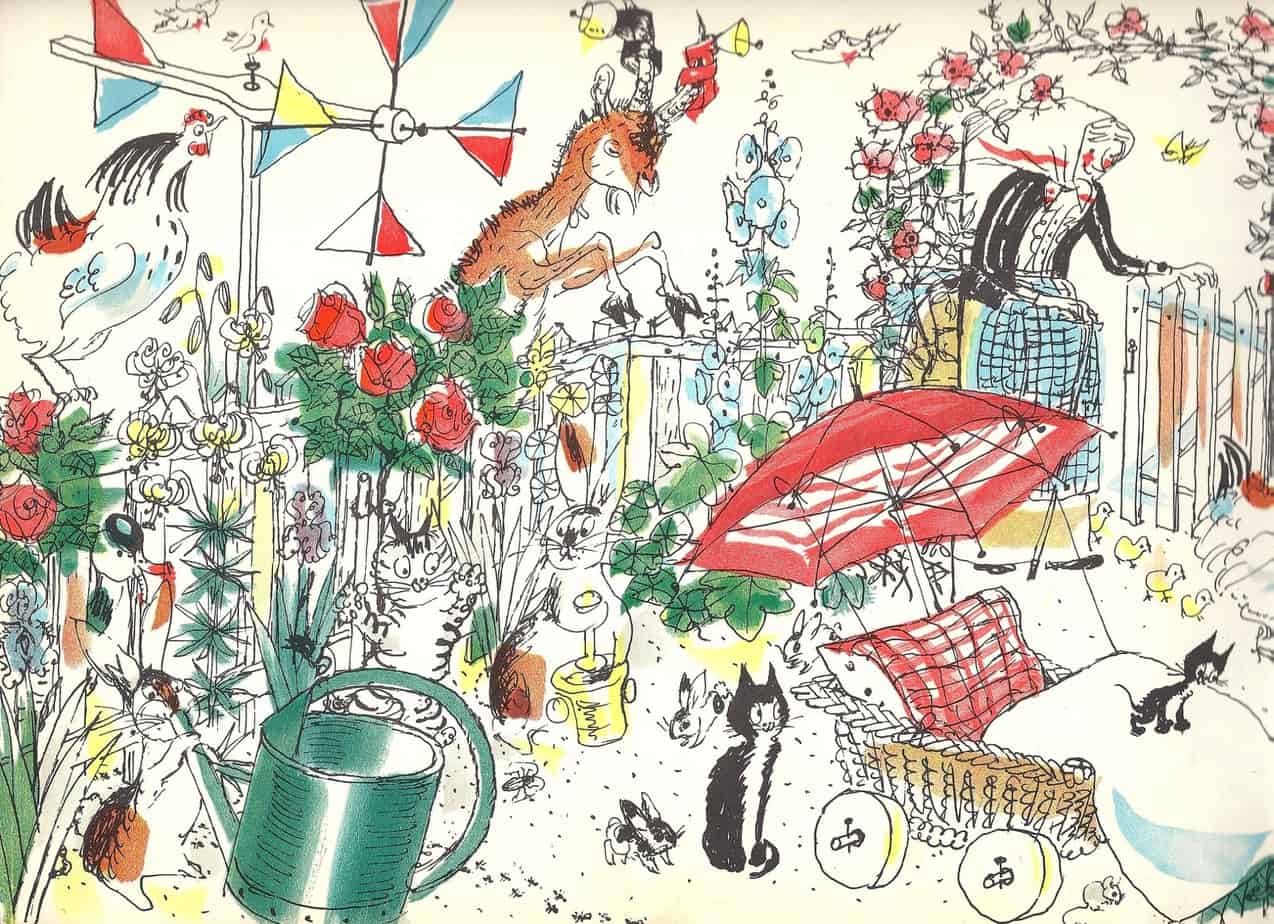

- ARENA — The whole story takes place within the boundaries of an old woman’s farm. Pitschi ventures as far as the chicken coop.

- MANMADE SPACES — A storybook farm.

- NATURAL SETTINGS — Although the arena is limited to the farm, for a tiny kitten, this massive space functions as a dangerous place. For instance, a drinking pond is as dangerous as a lake. It’s basically a shrinking story, though the main character starts out tiny.

- WEATHER — Like many utopian spaces, the weather is pleasant, probably between seasons, or early summer.

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — Technology is simple, for example the wire on the chicken coop, the sleeping basket, the shade umbrella, the pram.

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — We don’t know what’s going on outside this farm. But in world news, world war two had recently ended when this book was published. War-traumatised consumers were hungry for cosy stories for their children (and no doubt for themselves). PItschi fit the bill nicely.

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — The adult reader will look at this utopian environment and know that this is a safe, cosy arena, but the child reader is likely to feel the full force of terror, experienced vicariously via the kitten. The adult can see the fence, can see the ‘lake’ isn’t deep. The kitten acts on instinct, terrified by the fox even though the fox is unable to eat her. So although she is ‘wrong’ about the level of danger she is in, she’s not really? Because the fox has come to eat her, hoping for some chicken.

STORY STRUCTURE OF PITSCHI

Pitschi is Odyssean mythic structure, also known as a home-away-home story when applied specifically to children’s books.

PARATEXT

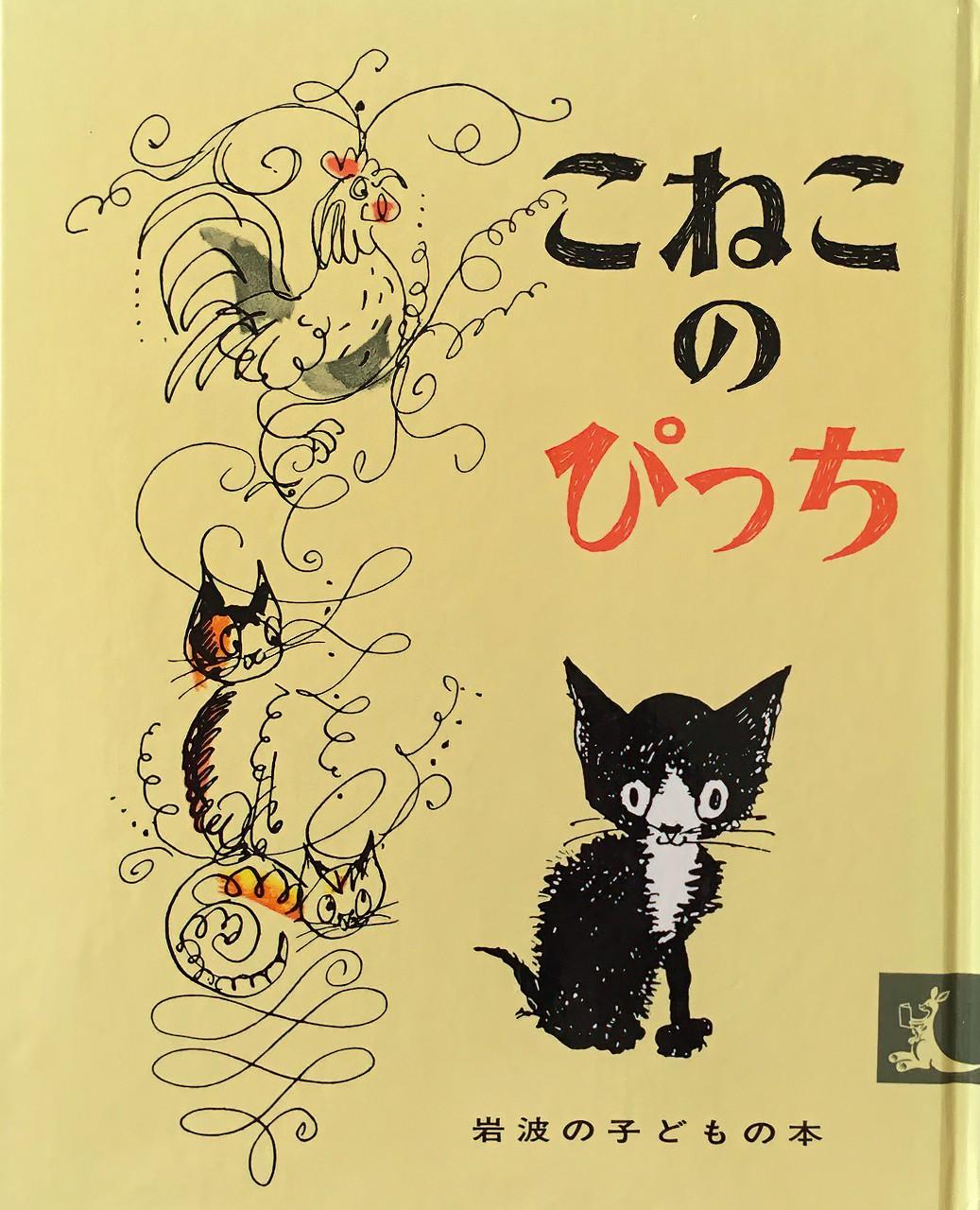

Pitschi was first published in Switzerland in 1947, then in the USA in 1953. This story is especially popular in Japan. I wonder if Hayao Miyazaki was inspired by Pitschi when he created Kuroneko (black cat) for Kiki’s Delivery Service. Alternatively, I believe Pitschi fits the Japanese concept of ‘cute cat’ very neatly.

Pitschi is sometimes subtitled: “The Kitten Who Always Wanted to Be Something Else: A Sad Story that Ends Well,” which is interesting because it assures adult gatekeepers that this is a cosy book suitable for very young children. There’s also a touch of comedy in that ‘teaser’ (because it’s also a spoiler, yet not a spoiler, because a children’s picture book which ends well is hardly new).

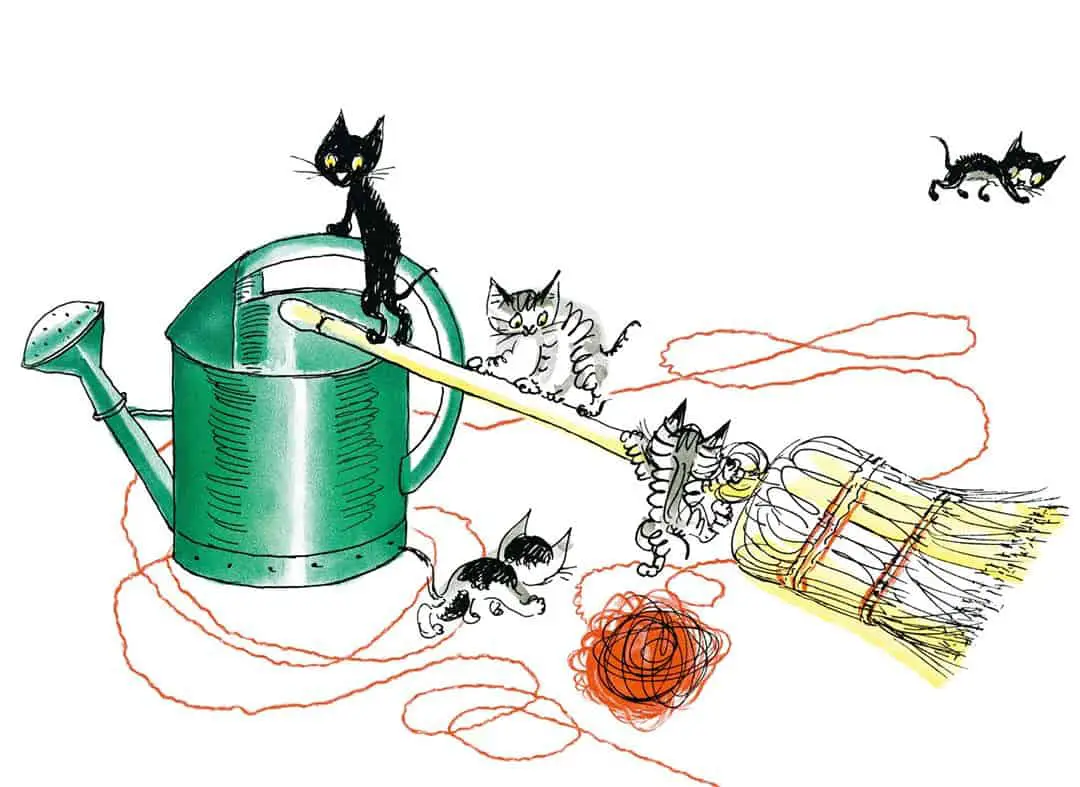

SHORTCOMING

The kitten’s great weakness is that she is very young, very small and very vulnerable. She also has the sort of temperament where she wants to go out and explore, without the protection of her mother, Old Lisette, or her litter. Vulnerability plus sensory seeking behaviour ain’t a great combo.

This is a story where a character leaves the safety of home and is basically punished for it, which is very post-war. Scuffy The Tugboat is another great example of a picture book which says, “Stay home, kids. That’s where you’re safe.”

I tried to find out what Pitschi means in German. It appears this kitten has been given an onomatopoeic symbolic name, which fully reveals itself at the calamitous climax:

Pitsche-patsche nass means something is soaking wet, because it resembles the sound someone walking with wet shoes (plitsch/platsch). The formal word would be “triefend”.

Reddit

There is also a German nursery rhyme “Pitsche, Patsche, Peter”, translated into English as “Pitty Patty Peter”. In short, it seems ‘Pitschi’ is an onomatopoeic German word whose variatns have a long association with children’s stories in German speaking spheres.

DESIRE

Unlike Scuffy (the Tugboat), Pischi doesn’t leave home out of some hubristic need to see the world. She seems to be entirely after novelty and adventure.

OPPONENT

This has elements of a cumulative tale in which the main character meets a variety of other characters along the way and the disasters get ever bigger. That said, I guess all mythic stories are cumulative in this sense.

PLAN

Insofar as a kitten can have a plan, it seems Pitschi wants to explore the world and have fun doing so. She tries on lots of different ‘hats’, really the narrative ‘mask’, but as in all mask stories, none of them fit because none of them are Pitschi’s ‘true self‘. She can only ever be happy as a kitten in an appropriately kitten environment, which is not in a chicken coop. (This will be revealed later.) This aspect of the story calls back to The Ugly Duckling. I’m sure The Ugly Duckling influenced Fischer, and various other storytellers who make use of bird species (in this case the chickens and rooster) when telling stories about animals who try to be a different kind of animal.

But further behind the Ugly Duckling plot is the real phenomenon in which some species of birds use other bird species to incubate their own eggs. This behaviour seems very strange to us mammals, who cannot (until very recently) use anyone else to make our babies for us.

Most birds build their own nests and incubate their own eggs. However, some birds like the cuckoo have managed to get around this inconvenience by simply laying their eggs in the nests of other species and letting someone else do the hard work of keeping the eggs warm and protected until the chick hatches. The ‘host’ (the poor sucker who ends up taking care of the other birds’ eggs) does everything they can to try and make sure the eggs that they’re sitting on are just their own. On the other hand, the ‘brood parasite’ (the freeloader bird that just lays in the nests of others) does everything they can to make their eggs indiscernible from the eggs of their host.

Scientific American

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The ‘rule’ of this part of a story: The character comes close to death. What does that look like in children’s books? It quite often involves getting wet. Getting wet is coded as comical, unless you know the drowning stats (children themselves don’t).

Because this is a mythic structure, there is a succession of battles. The truly scary part happens at night with the visitation of the fox. However, Fischer has made sure to draw a nice, safe chicken wire barrier between the kitten and the fox, who opens its maw hungrily and scarily, looking wolfish as much as foxy.

ANAGNORISIS

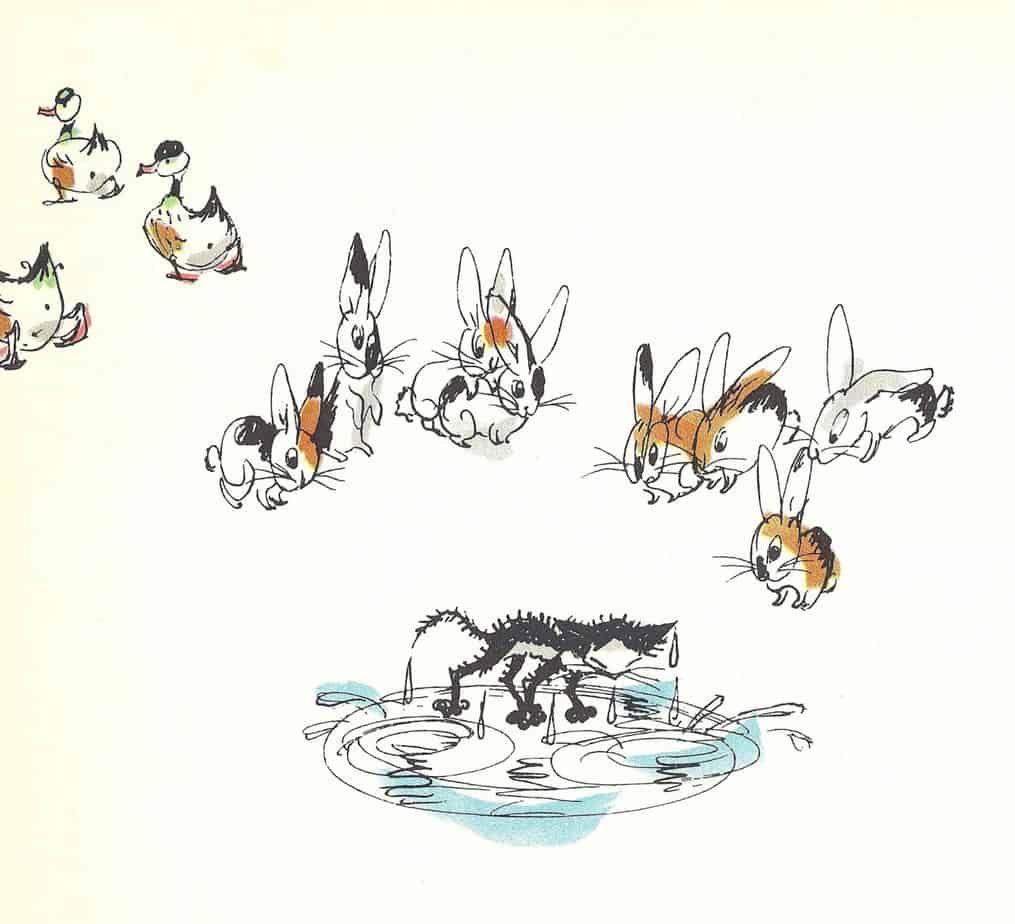

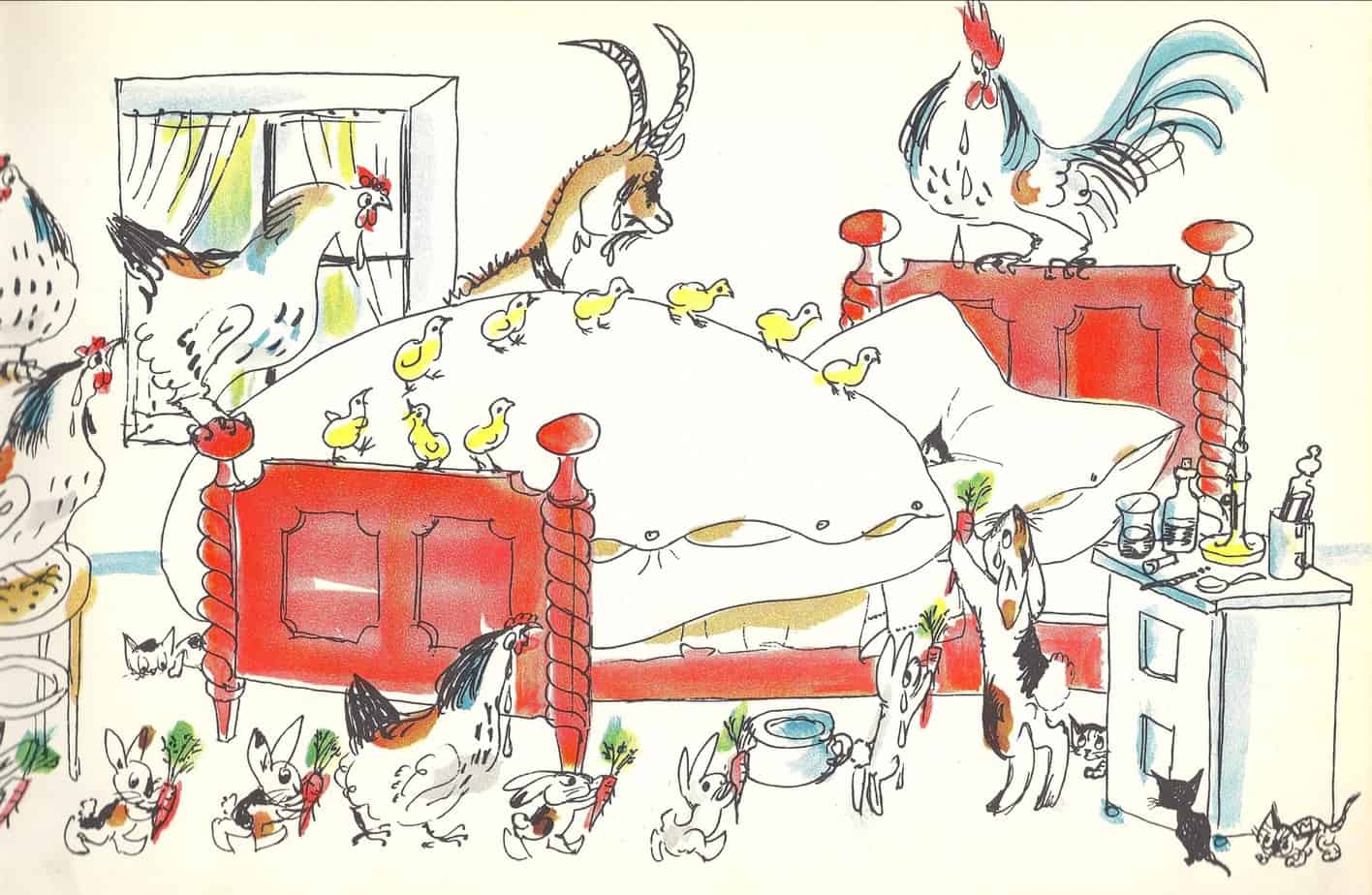

The post-Battle phase of this story is quite substantial compared to many stories. Pitschi will learn that she has many friends right there at the utopian farm. They all look after her as she convalesces.

I’m noticing more and more as I delve into children’s books of earlier golden eras that convalescence plays a much more significant role than it does today, in which characters who go through trauma are expected to get straight back on their feet. (I’m sure that says something terrible about modern life in general.) Like the ending of Bill Peet’s Fly Homer Fly, this empathetic main character is nursed back to health by other characters and realises she is not lonely after all. All that caring proves it.

The convalescence trope can also be seen in Regency romances such as Pride and Prejudice. It doesn’t take much for Jane Bennett to get severely ill — all she does is gets caught in some rain. I conclude she wasn’t really sick. (Jane Bennett was a trickster, albeit a sweet one, unlike her mother.)

To be cared for is to be loved. In each of these cases, the character goes out in the night or the elements, gets soaked to the bone and supposedly the cold itself leads to illness. No wonder it has long been thought that cold air causes ‘colds’. (It really does seem to, if only because we are frequently fighting off viruses and don’t even know it, until we really test our system by getting really cold.) I wonder how many of those old stories are really about hypothermia?

NEW SITUATION

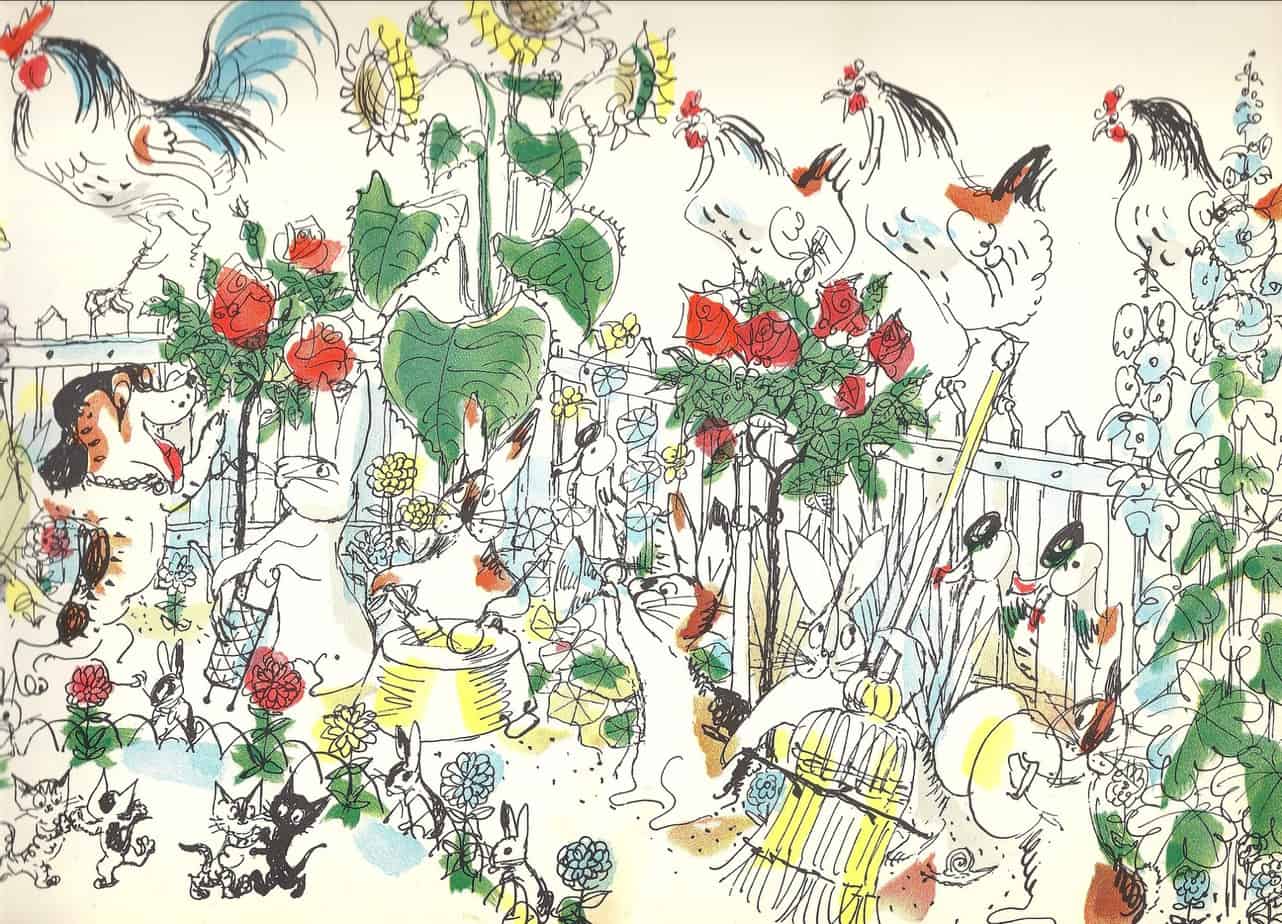

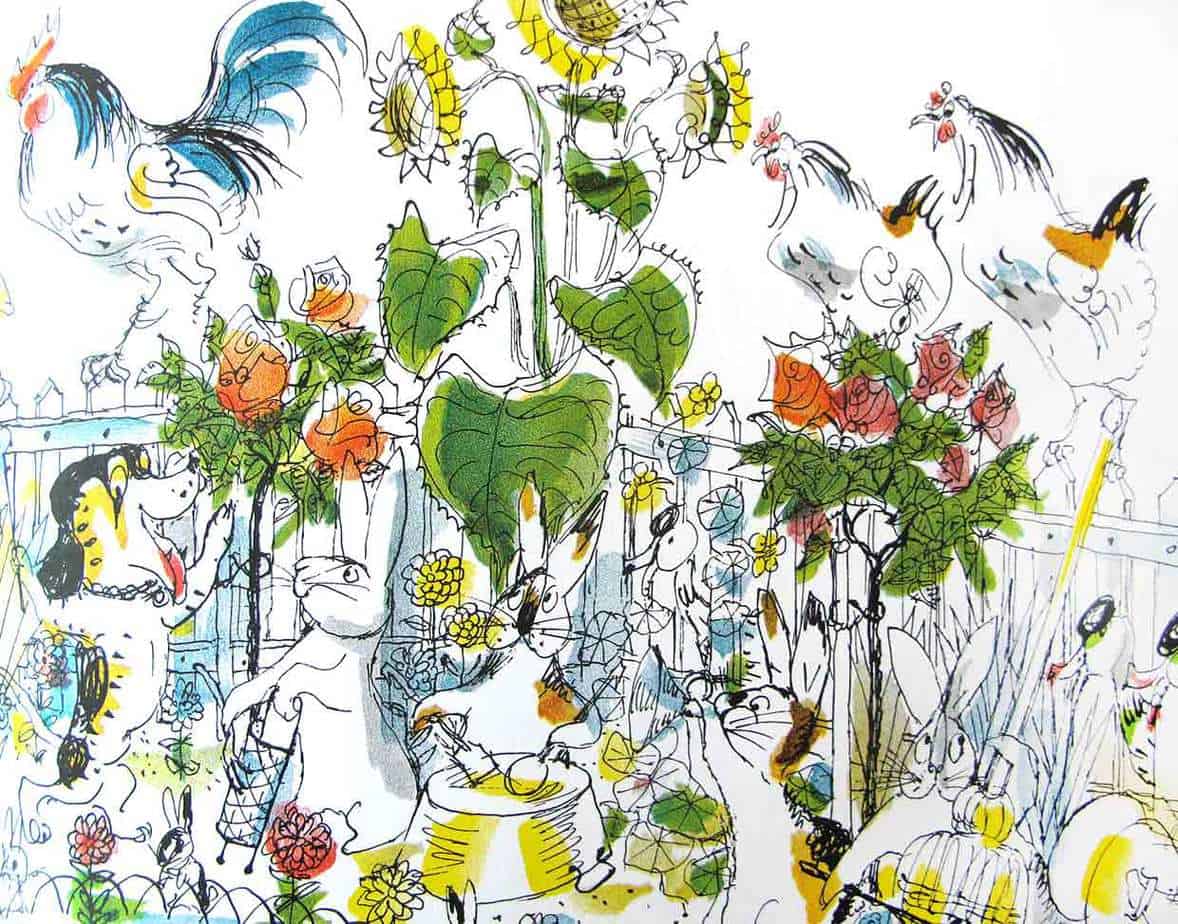

The animals rally round Pitschi. There’s safety in numbers. This utopian scene is a wordless double spread.

This scene is followed by the animals sitting down together to enjoy a cake with cream. This was the era of sugar. Sugar was rationed during the war, and post-war parents lavished their children with it. My father, born 1942, grew up drinking 8 teaspoons of sugar in his tea. After experiencing food insecurity, we commonly wish to feast.

War aside, food is really important across children’s stories in general.

From that moment on, Pitschi didn’t want to be anything but a kitten.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

After that harrowing experience as a kitten, I’m guessing Pitschi will live the life of an archetypal fat and lazy housecat, adored and fed lavishly by Old Lisette. She’ll probably basically turn into Garfield.

RESONANCE

Though not all reprintings are worthy, this one is. North South re-released Pitschi in 2010, introducing the plucky, adventurous, lovable kitten to a new audience. The folktale backbone ensures the plot will continue to resonate with audiences for many years to come.

To what extent do modern picture books punish children for leaving home, though? Not so many. But in a post covid-19 world, it will be interesting to see what happens to picture books.

FURTHER READING

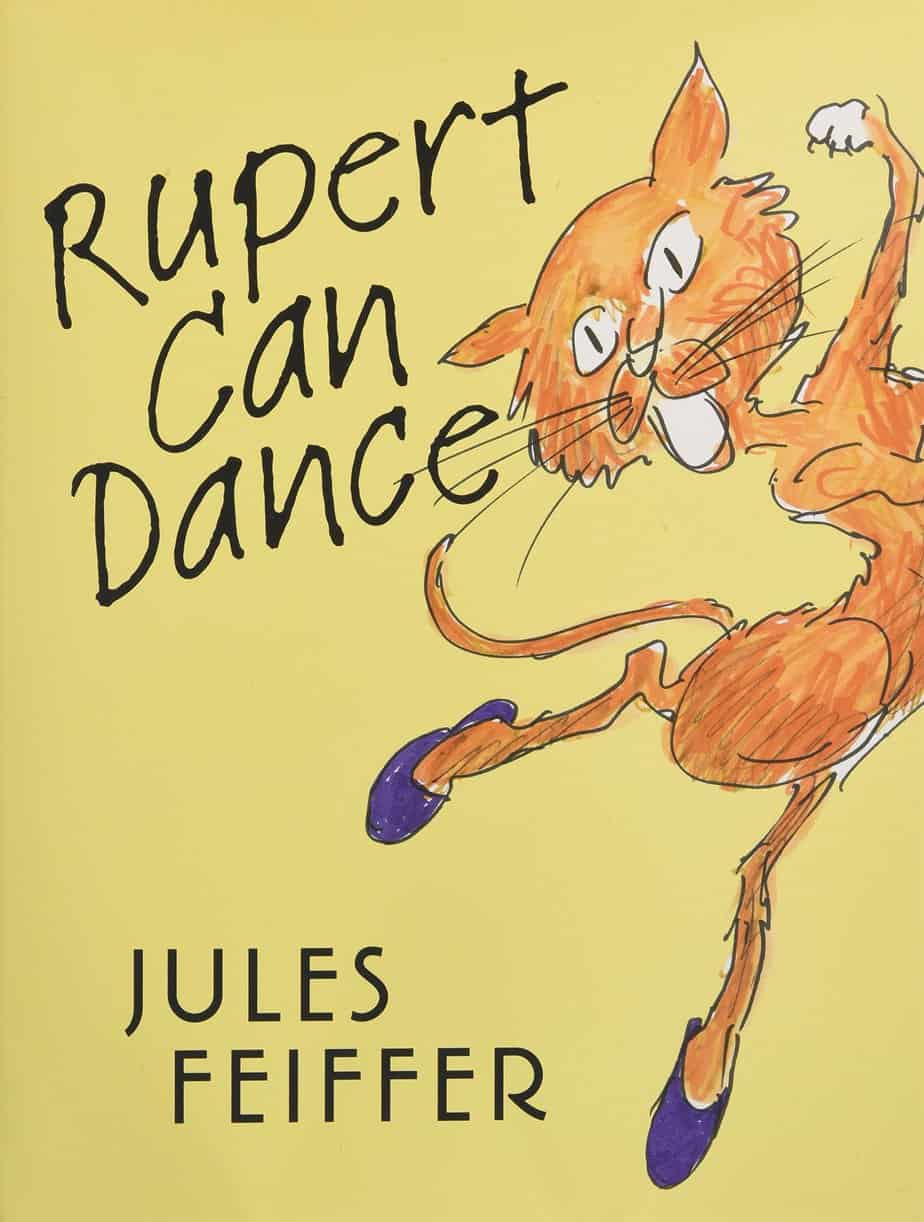

If you enjoy Hans Fischer’s illustration, check out art by Jules Feiffer, who also drew humorous, expressive, sketchy cats doing funny things.