The Pigeon Wants A Puppy by Mo Willems is one of my kid’s favourite books. The Pigeon books are similar to the Elephant and Piggie books in graphic design and in humour.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE PIGEON WANTS A PUPPY

SHORTCOMING

When I read this quote from the author/illustrator I knew that Willems thinks of story in the same way I do:

I don’t know if I can explain him — I can describe him. Pigeon has wants and needs and desires, and he has very few filters. He wants what he wants, he thinks he needs what he needs. He is railing at the injustice of it all. And the irony is that the kids who are usually suffering the injustice of it all, the kids who are being told when to go to bed, or what to do, or to eat, or how to eat, or how to dress — the second they get to stick it to the pigeon, they do.

I try to think that the Pigeon is a core, fundamental, philosophical being. He is asking the fundamental, deep questions: What is love? Why are things the way they are? Why can’t I get what I want? Why can’t I drive a bus? I mean, you know, Sophocles.

Mo Willems, NPR

DESIRE

The desire is right there in the title. Perhaps not much more needs saying.

Oh, except note how masterfully Willems has connected Desire to Shortcoming. This is always the best form of Desire in a story, returning the best results: Pigeon desires a puppy because he fails to do his research and understand consequences. He acts on his whims.

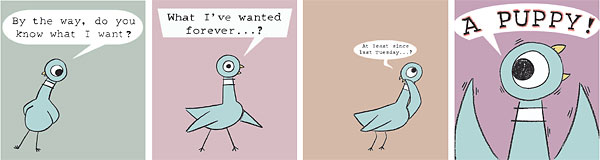

Note also: Willems is really ramming home the Desire line. There’s much humour in this because of pigeon’s complete lack of self-awareness. Of course he hasn’t wanted a puppy ‘for ages’. He’s decided right then and there. (If we didn’t already suspect that, we learn it by the end.)

By the way, the image on the colophon page perfectly illustrates how Willems may have brainstormed this series. We see list unwinding, headed “Things I Want”:

- Drive a bus!

- Eat a hot dog all by myself!

- Stay up late!

- Real estate!

- A big, red truck!

- Turtleneck sweaters!

- A driver’s license!

This list encapsulates pigeon’s whimsical desires at the centre of other books in the series — a comedic mixture of childlike (big, red truck) and mature (real estate).

OPPONENT

The main opposition is the puppy, who stands in direct opposition to Pigeon’s desire because she doesn’t live up to Pigeon’s idealised conception of what a puppy would be.

In this way, the Opponent of The Pigeon Wants A Puppy is similar to the opponent in a crime story because the audience doesn’t see the villain until the big reveal near the end. There’s no crime here, of course. But the storytelling problem is the same: The storyteller must really build up the opposition

- to create payoff at the end

- to give the main part of the story its narrative drive

What crime writers do: Create other opponents along the way, much like mythic structure. Opponents apart from the main one, that is. (Family, colleagues, uncooperative politicians who won’t hand over the information you need etc.)

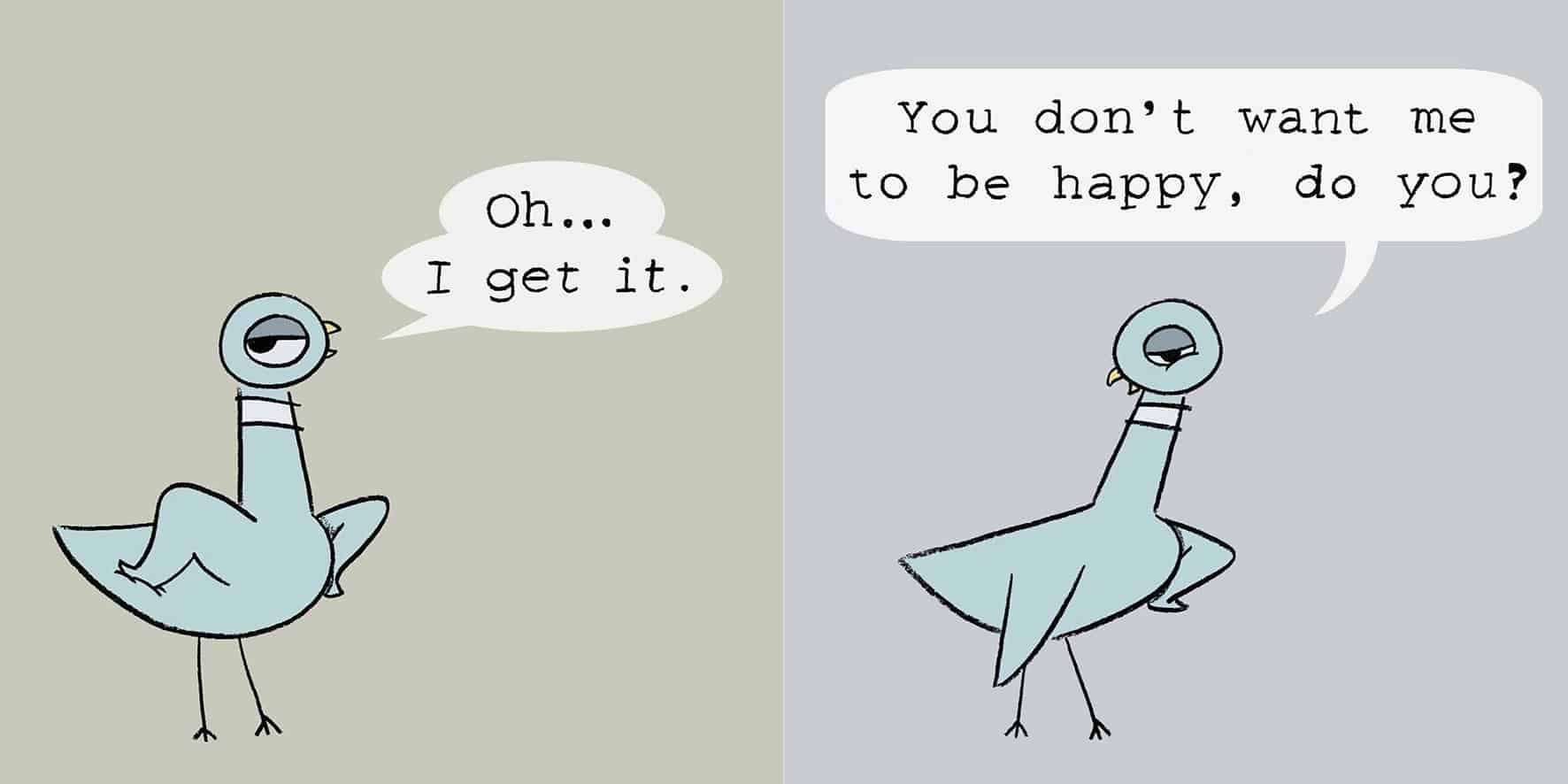

How has Willems created extra opposition, apart from the unseen ironic ‘villain’ of the puppy? Yep, he makes THE READER part of the pigeon’s web of opposition. It’s masterful. Willems achieves this by using the narrative technique of direct address.

PLAN

Pigeon has a Plan which demonstrates to the reader, in audience superior position, that Pigeon has NO idea what a puppy even is. Pigeon plans to:

- water it once a month

- go for piggyback rides on its back

- play tennis with it

Notice how Willems made use of the Rule of Three — three specific things Pigeon plans to do with a new puppy.

BIG STRUGGLE

In picture books the Battle tends to comprise a large proportion of the total story. It tends to be a Battle Sequence.

Picture book author Katrina Moore thinks of picture book structure like this:

- Set up (how much Pigeon wants the puppy and how he is wrong about puppies)

- Escalation (Woof! What’s that? Woof! Woof!)

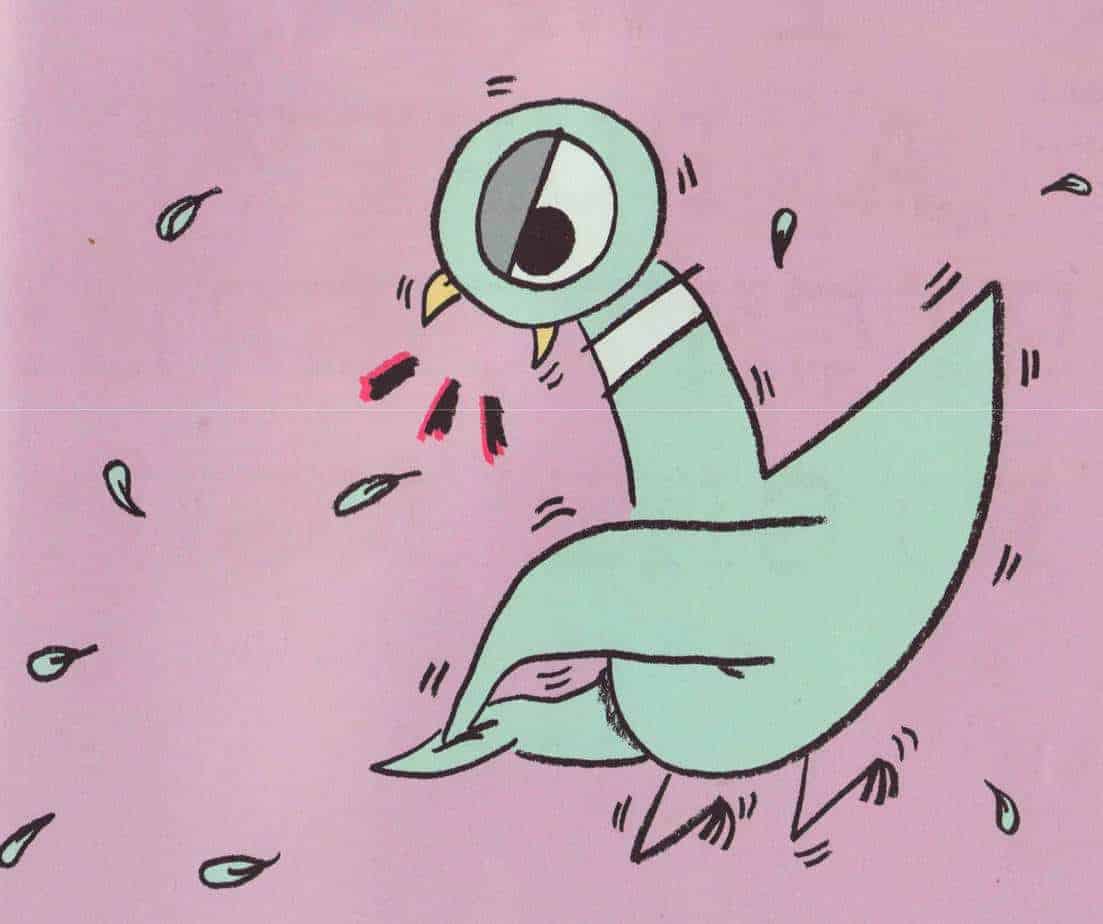

- Climax/Low Point (Pigeon gets scared half to death by a massive puppy head coming onto the page — by the way, notice how Pigeon is now facing backwards, opposite to the turn of the page? He has had a shock — this is common picture book convention.)

- Resolution (what I’d call the Anagnorisis, though this may be a better word for it, since so often there is no Anagnorisis)

- Wink (the reader knows this exact scenario will play out twice)

(For more on the Battle sequence and the forms it tends to take in picture books, see my post on Battles in Storytelling.)

ANAGNORISIS

“Really, I had no idea!”

The comedic thing about this particular Anagnorisis: Pigeon is unable to generalise learning to new situations. He (or she) learns that PUPPIES are not as expected but fails to learn that maybe WALRUSES won’t be, either.

NEW SITUATION

I recently read We Learn Nothing — essays by Tim Kreider and I believe it’s more common we learn nothing than learn something, in fact. No life lesson is learned. Just a very specific one. In this respect, Pigeon is identical to Aaron Blabey’s Pig The Pug, who learns a very specific aspect of Not Being An Asshole in every book, but there are so many different ways of being an asshole an entire series has been generated from Pig’s assholery.

At the end — ‘the wink’ — Pigeon wants another wholly unsuitable pet. This makes the story a circular plot, ending where it began with slightly different variables, w swapped out for p.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS

The front cover says ‘pictures’. Is this simply because toddlers will understand ‘pictures’ but may not understand ‘illustrations’? I suspect there’s more to it than that — these are perhaps better described as pictures.

Every single thing in these minimalist picture books is there because it carries meaning. There is no background detail. These are stories about plot (centred on character) — they are not the sort of books in which the reader is invited to linger, enjoying the environment e.g. Blackdog by Levi Pinfold or anything by Shaun Tan.

It’s ultimately reductive, but my sort of cheat sheet is: If you were to look at all of my drawings [for a book] without any words and understand it, then there are too many drawings. The drawings are too detailed. And if you were to read the entire manuscript and it made sense, then there are too many words.

So it’s that marriage, that very delicate marriage between words and pictures, and then that marriage between author and audience where the audience is creating so much of the meaning. So my job is to create incomprehensible books for illiterates.

Mo Willems, NPR

How do picture book illustrators handle the delicate issue of swearing in children’s literature? Well, Pigeon clearly utters expletives here.

Other techniques derive from comic book convention, for instance the love hearts all around the speech bubble.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST WITH BABYMOUSE: PUPPY LOVE

The Puppy Love book of the Babymouse series by Jennier and Matthew Holm has a similar plot structure but expanded into a middle grade graphic novel length. Babymouse goes through a series of pets but proves an unreliable owner. Each of her pets escapes. Eventually a stray dog turns up. Owning a dog is not what she hoped it would be. The dog gets up to mischief, first chewing her shoes and clothes, then chewing her entire room.

The story ends when the dog’s owner comes to get it. (Behind the scenes the mother must have put out the word about finding a lost dog.) The plot reveal is that the dog is a girl, not a boy as Babymouse had assumed.

In an ideal world this would not be a reveal, but studies have shown that animal characters are automatically coded male unless given an obvious feminine marker, such as the bow Babymouse herself wears on her forehead. So this ending asks readers to perhaps not assume, next time, that an animal who gets up to mischief MUST be male.

The other interesting thing about Babymouse is how every character in the story is an animal. Babymouse, her family and classmates are all animals, but in shape only. They are otherwise completely human. But animals who behave like regular animals also exist in the story. Of course, no explanation is given for this, and I doubt the typical reader would even think about it.

FURTHER READING

The Easy Acquisition Of Pets In Children’s Stories

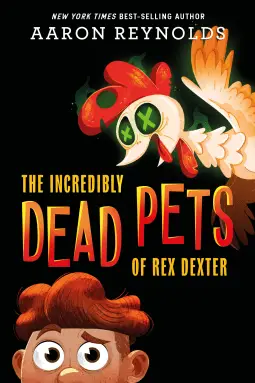

Rex Dexter is itching to have a dog. He was practically born to have one. His name is Rex, for crying out loud. It’s a dog’s name. Any pooch is preferable, but a chocolate Labrador is the pinnacle. The best of the best. The dream of all dreams.

When Rex’s B-Day for Me-Day finally arrives, his parents surprise him with a box. A box with holes. A box with holes and adorable scratchy noises coming from inside. Could it be? Yes! It has to be! A . . . a . . .

Chicken?

Pet poultry?

How clucky.

One hour and fourteen minutes later, the chicken is dead (by a steamroller), Rex is cursed (by the Grim Reaper), and wild animals are haunting Rex’s room (hounding him for answers). Even his best friend Darvish is not going to believe this, and that kid believes everything.