Who Wants To Be A Poodle I Don’t is my favourite Lauren Child picture book. I can see it being used in the classroom to teach the concept of the leitmotif, among other things.

This is a picture book written and illustrated by British kid-lit master, Lauren Child of Charlie and Lola fame.

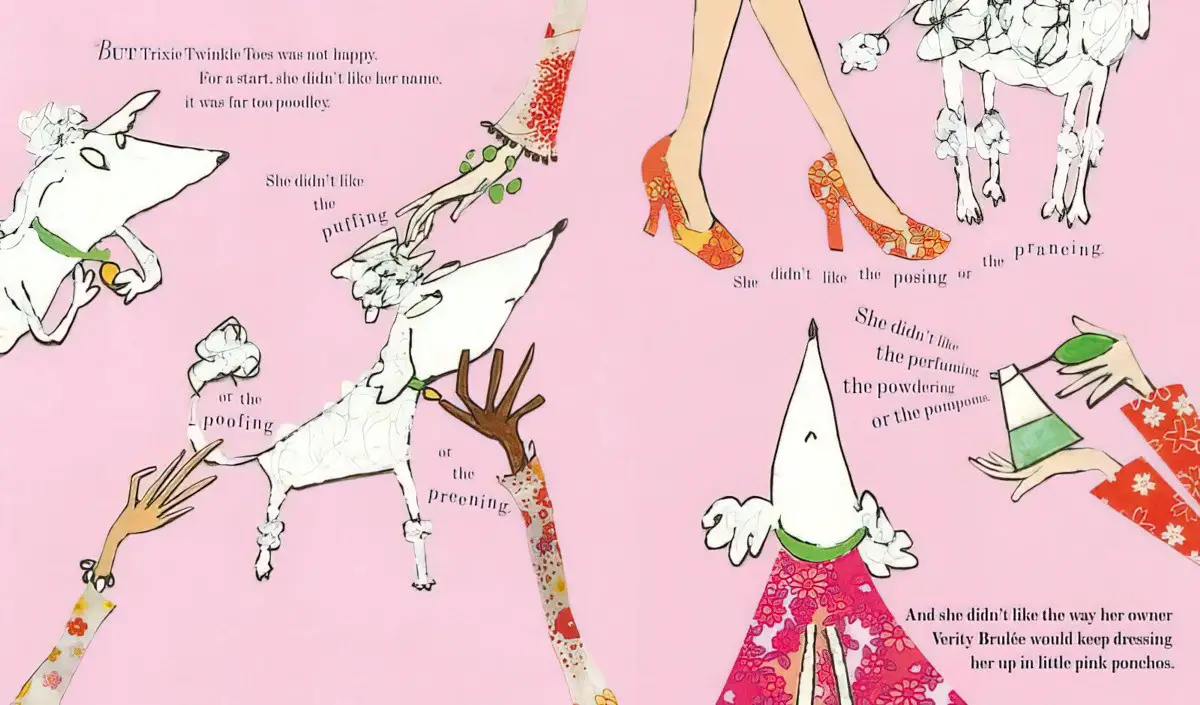

The story might be used in the older classroom or with a child reader to discuss sound devices and alliteration, for starters.

In particular, Who Wants To Be A Poodle I Don’t is a wonderful example of the leitmotif, in which sound devices are used to tell us more about a character.

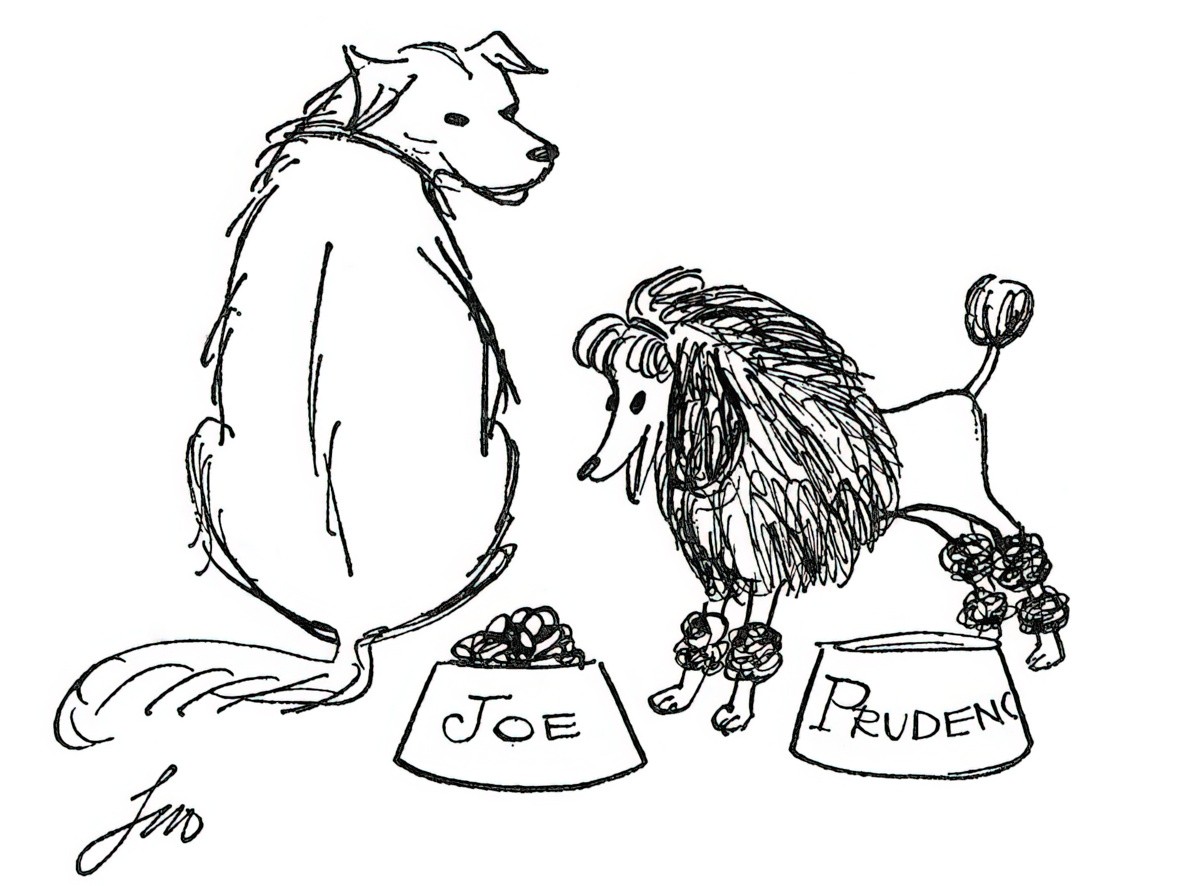

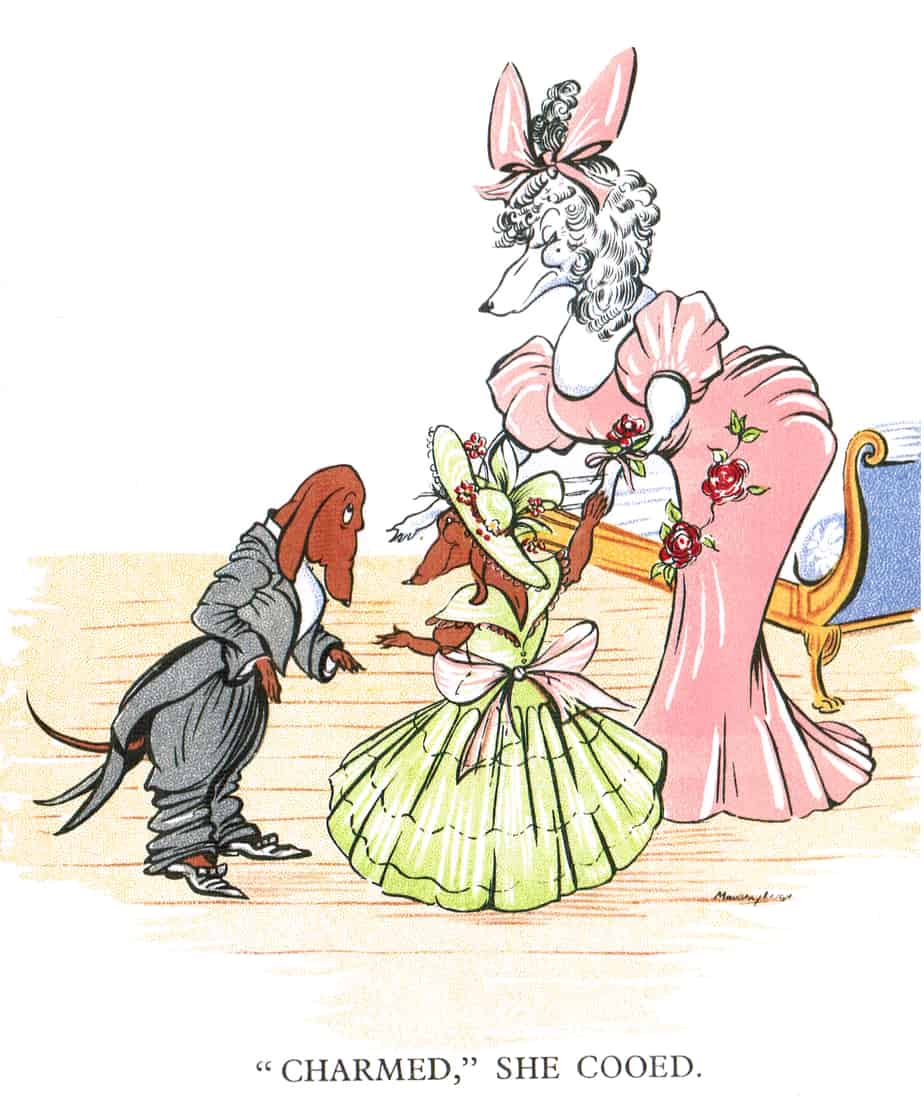

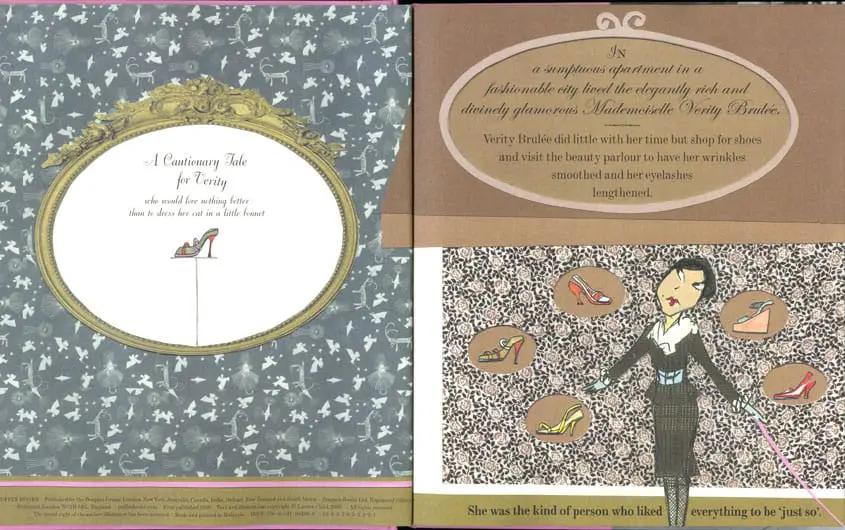

This story — like many picture books — is a wonderful example of how character names can say a lot in fiction. Why is Mademoiselle Verity Brulée named as such? In the Anglo world, what connotations are associated with the French? Since crème brûlée is a kind of sweet dessert, what might we surmise about this character?

Crème brûlée…is a dessert consisting of a rich custard base topped with a contrasting layer of hard caramel.

Wikipedia

Perhaps Verity has both soft and hard edges to her personality. Perhaps the contrast of textures in this particular dish is symbolic of how two characters living together as one family can have such different temperaments that they are like chalk and cheese. However, it is precisely the contrast in textures of the crème brûlée that make it work so well as a dessert. If only Trixie and Verity can learn to live with each other they’ll make a great team.

Ideology Of Who Wants To Be A Poodle I Don’t

“Dogs should be left to be dogs, not treated as toys to be groomed and molly-coddled.”

Since, in children’s stories, animals are stand-ins for children, the ideology is therefore also that children should be allowed to be children, free to run around parks and get themselves dirty.

Notes On The Illustration Of Who Wants To Be A Poodle I Don’t

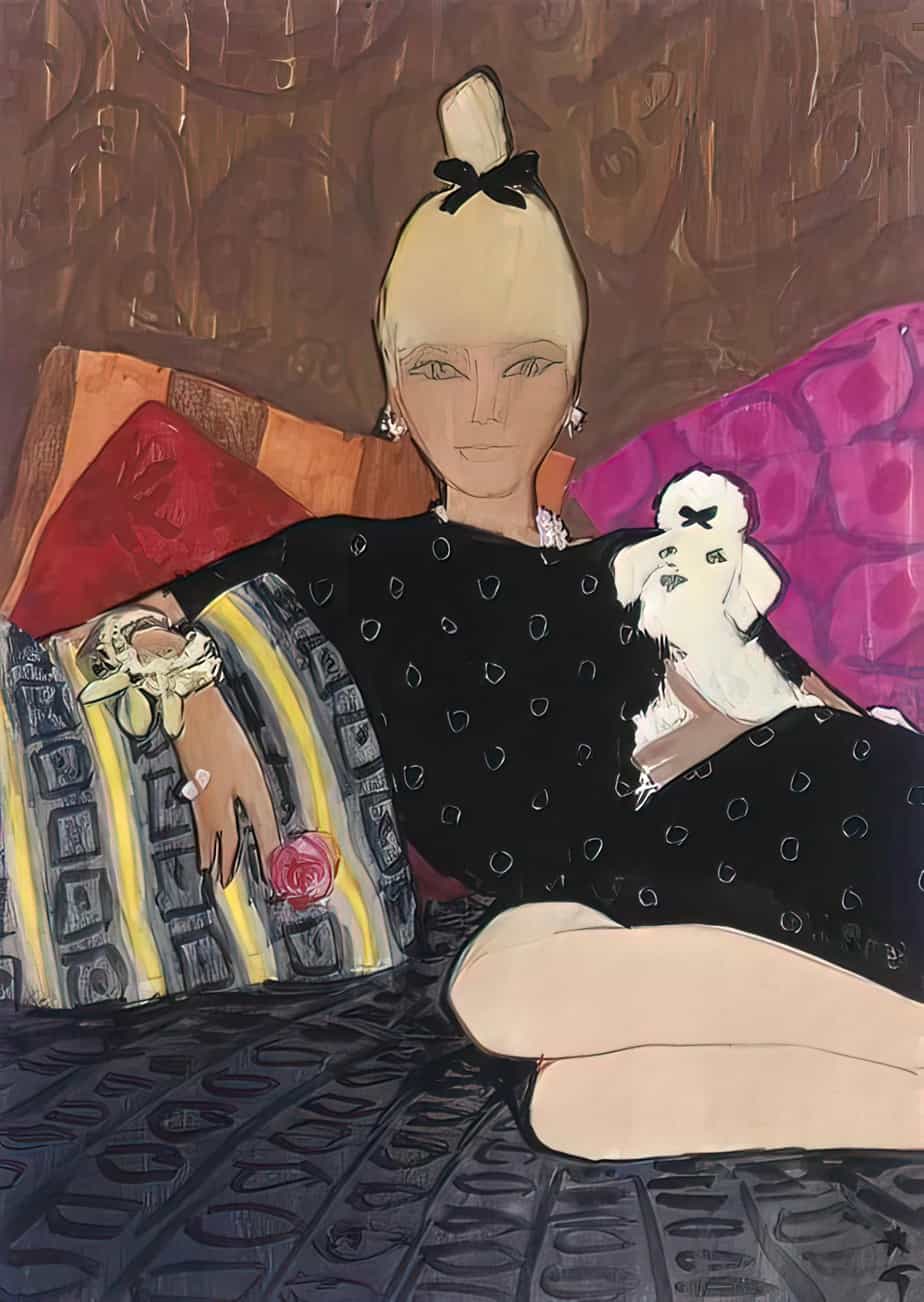

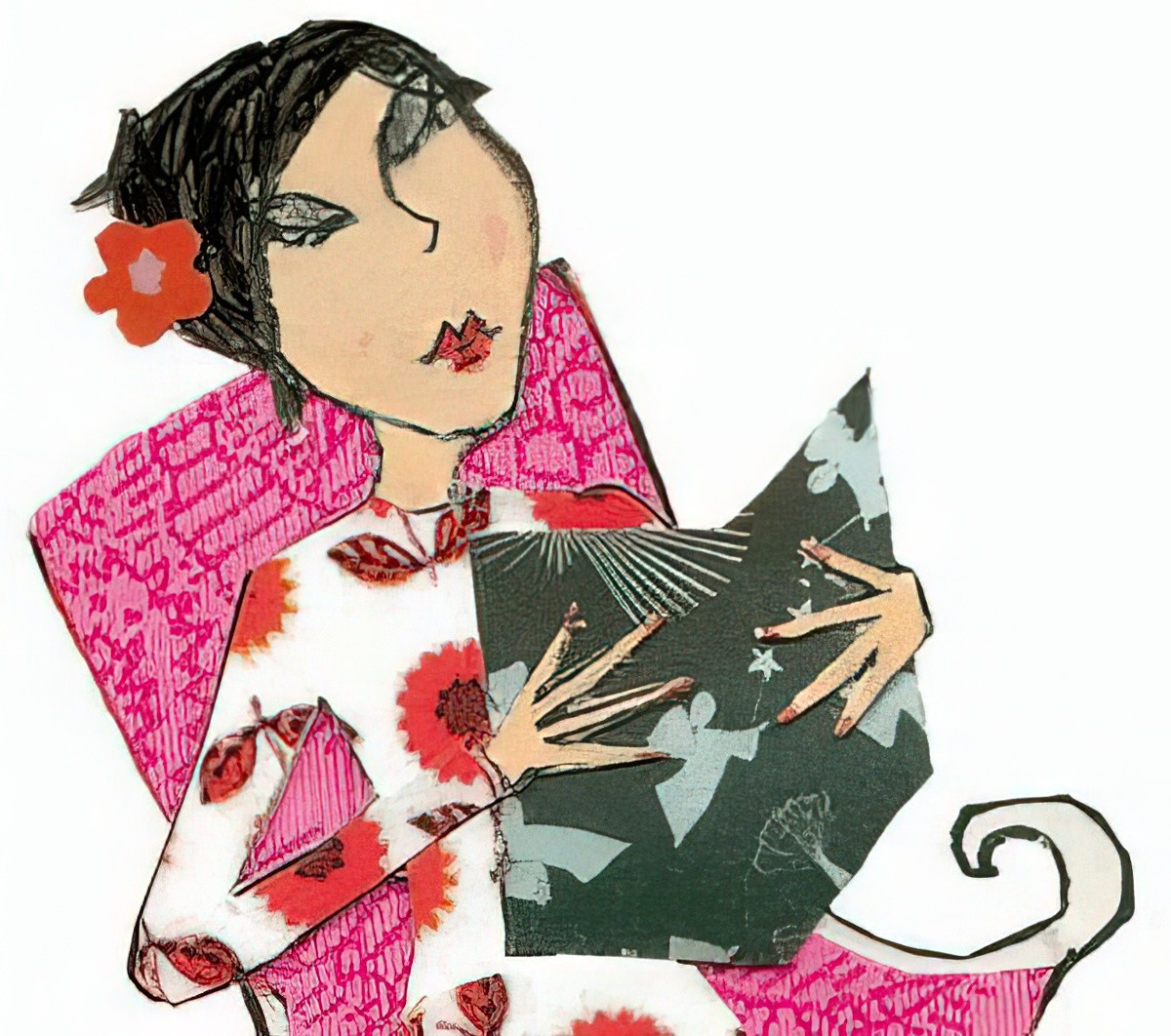

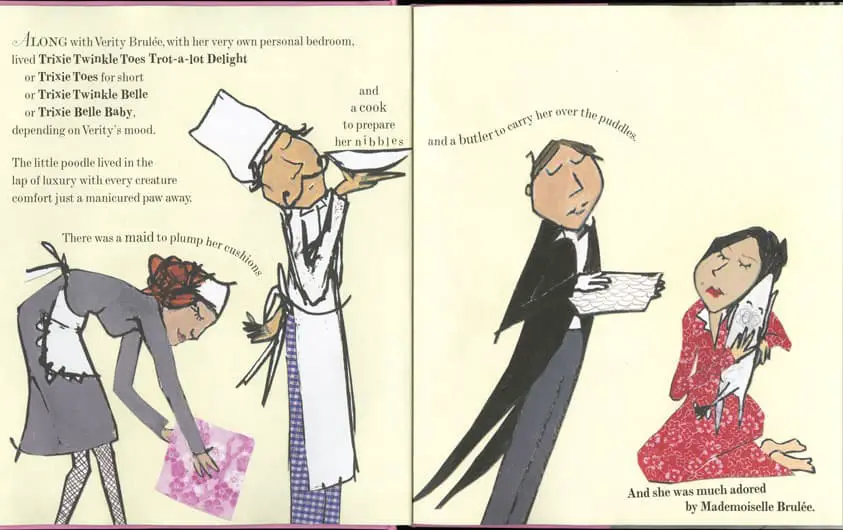

This book is illustrated in a similar style to the Charlie and Lola series, though Charlie and Lola books make quite heavy use of collage, in which photographs appear to have been cut out and stuck on. This book retains the feel of collage but doesn’t employ that exact technique. Instead, I’m reminded more of the Japanese kimono, with its distinctive admixture of highly detailed patterns. I’m sure this is intended, since Verity is seen at one point wearing a kimono inspired dressing gown. (I believe they’re just called ‘kimonos’ in the West.)

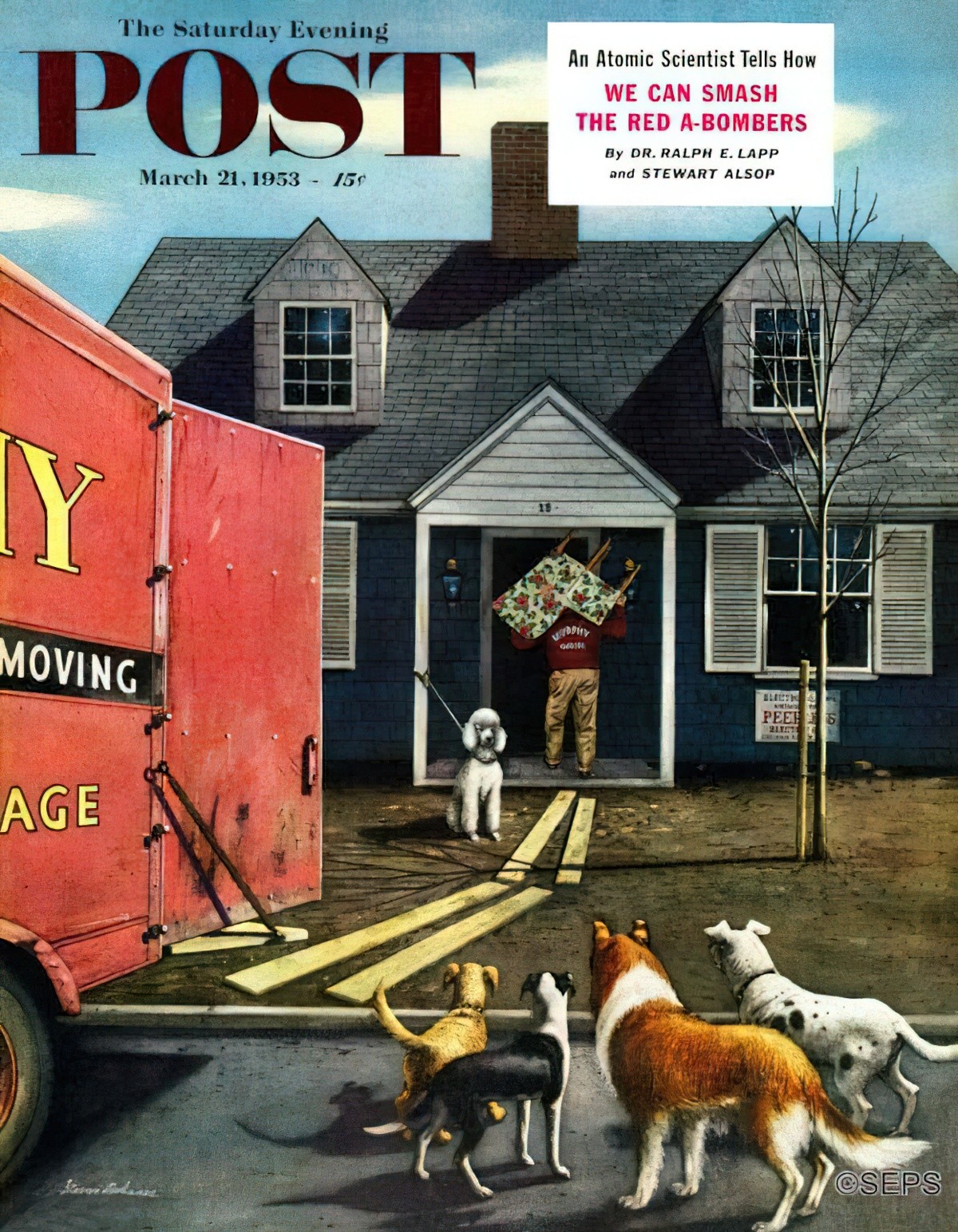

The setting might be in Paris or in England or America — the era feels a bit 1920s, but we do see a retro style TV, which places it more squarely in the 1950s — before the Aristocracy had died, in any case.

The scribbly/collage illustration style of Lauren Child, in which the rules of perspective are thrown out the window, lends a childlike, playful feel to everything she writes, and encourages us to poke fun at the characters and to look for humour which we may have to dig just a little deeper for. These characters are ‘off-kilter’ and ‘quirky’, like the illustration itself. The childlike nature of the story is evident even in the punctuation (or lack thereof) on the cover: The title is a run on sentence and lauren child does not capitalise her name on book covers.

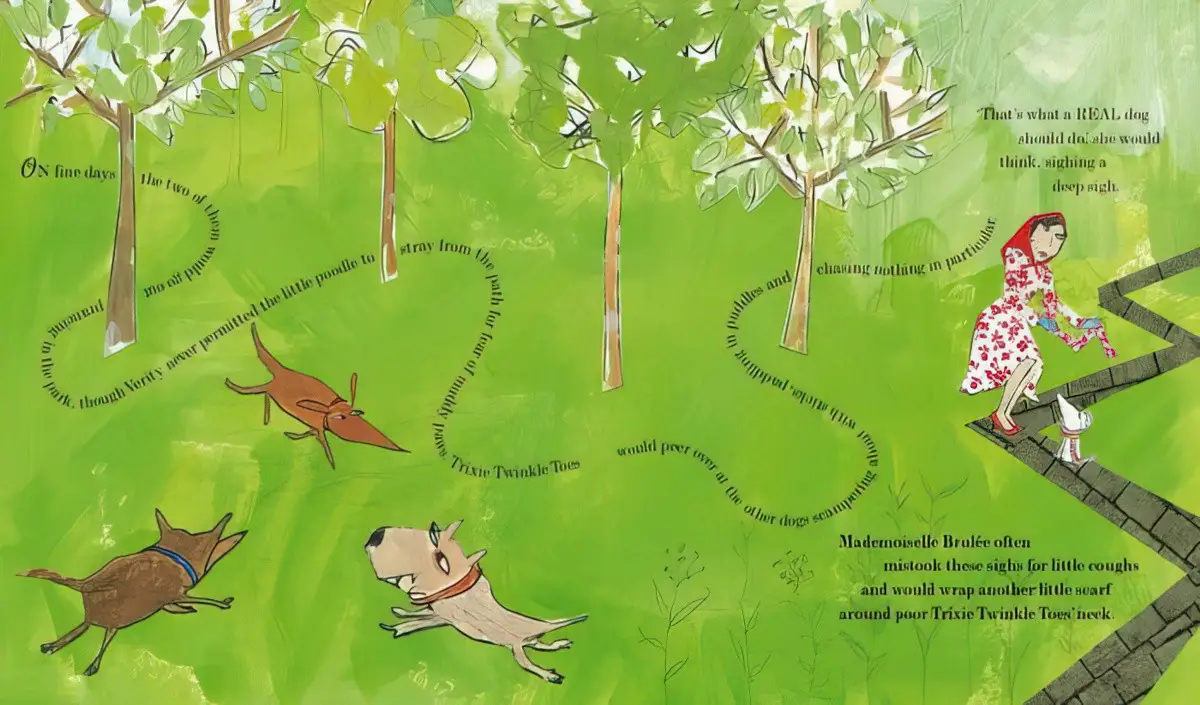

The text in this book requires advanced decoding skills, which is an interesting development in picturebooks since ‘type text to path’ became so easy in Photoshop. Illustrators and book designers can now design pages with any sort of shape to their words. In this book we have the text fully integrated with the pictures, and the reader is challenged at times to find the book text among the intratext, to slide down the page then defy the rules of reading and read up the page and even to read in circles. Coupled with the advanced language in this book, I’d say it’s a picture book designed to be read to children by an experienced older reader (rather than as an independent scaffolded exercise).

STORY STRUCTURE

Who is the main character in this story — Verity Brulée or her miniature poodle Trixie Twinkle Toes Trot-a-lot Delight? The answer to that question is always: Which character changes the most? In which case, the dog and the woman are one and the same character. Trixie Twinkle Toes is a canine manifestation of the part of Verity who feels the social pressure to be ‘perfect’: ladylike and manicured and everything ‘just so’.

SHORTCOMING

Verity Brulée is inflexible and has perfectionist tendencies, preferencing image over practicality. Her dog Twinkle Toes is a dog, and therefore needs to do doglike things in order to be happy. These two characters are trapped together in the same place, which is a requirement for any kind of significant narrative conflict.

Trixie Twinkle Toes does not like her name or any of the rituals that go with being an upper-class dog.

DESIRE

Verity wants to own a dog who is pretty and well-behaved while looking rich and well-groomed. She wants to perfume, powder and pom-pom her poodle and dress her in pink ribbons. She wants to keep her little dog happy and healthy — constantly wrapping Trixie up at the first sign of a cold — but she misunderstands her pet due to communication difficulties. (The dog can’t speak English.)

Trixie wants to step in puddles. She wants a different name. She wants to brave and adventurous. She wants to do something rather than seem something.

Trixie’s dissatisfaction comes to a head at the point in the story which switches from ‘iterative’ to ‘singulative‘. The first part of the book is about how things always are, and describes how they (often) go to the park and how Verity (often) dresses Trixie up. Now:

One night Trixie Twinkle Toes was lying in her room listening to the real dogs howling at the moon.

This is the event that instigates Trixie’s anagnorisis: “I hate being a poooooodle”.

OPPONENT

Verity and Trixie are each others’ opponents, symbolising the internal conflict between being free and being self-restrained. So when Trixie complains that she hates being a poodle, Verity completely misunderstands why she is crying and takes her to the vet, where very cleverly, the vet finds nothing but a sore throat. This is masterful because the young reader is left to fill in a gap: That Trixie’s sore throat is due not to having a cold but to howling.

This story is a good example of a pair of fictional opponents who have each other’s best interests in mind but end up standing in each other’s way due to communication difficulties, separate agendas and poor empathy. We often see this dynamic in husband/wife stories, or between parent and child in young adult fiction. Opponents are often members of one’s own family.

PLAN

At the dog salon Trixie sees a before and after picture of a scruffy to well-groomed dog and realises that it can work both ways. Her plan is to become a scruffy dog. She plans to (and does) catch some fleas after chasing a cat and chew Mr Chomley’s newspaper.

Verity foils this plan to become scruffy by telephoning her pet psychic. When the psychic sees nothing in Verity’s cup but ‘two lonely tea leaves’ this provides for obvious and humorous symbolism, showing the young reader that although Verity and Trixie live together, they are each lonely.

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle between Verity and Trixie is a constant swing between Trixie getting herself messed up and Verity putting it ‘right’ with visits to the pet salon and extra grooming sessions and eventually a pooch psychologist. This part of the big struggle conforms to the law of threes in storytelling:

- The poodle parlour

- The psychic

- The pooch psychiatrist

Notice, too, all of that wonderful alliteration with the plosive ‘p’ — basically a ‘b’ sound which is bursting to escape. (Psychiatrist is technically a sibilant, but we’ll go with what’s on the page.)

All this to-ing and fro-ing aside, in a memorable story we need some sort of climactic big struggle. In a novel we might get a lot of time spent on the psychological turmoil of the main character and not need a set piece, but picturebooks are more like films in this regard. The set piece (big budget scene arranged to maximum effect) in this story is the part where Trixie gets the chance to save another little dog by diving into a puddle. Again with the ‘p’ (puddle).

ANAGNORISIS

Even more masterfully, the alliteration during the puddle scene changes to ‘d’: ‘dazzling’, ‘daring’ and ‘dangerous’. The careful reader will notice (or at least sense) that Trixie is less ‘poodle’, more ‘d’ for ‘dog’! The transformation in the puddle has happened. In case we missed the way the alliteration is related to the story we have it reinforced on the following spread:

Verity Brulée looked at Trixie Twinkle Toes and saw not a little pompommed toy poodle but instead a DAZZLINGLY DANGEROUS DARING dog.

NEW SITUATION

The thing about picturebooks is that they don’t take themselves too seriously, and authors are free to signpost their plot points with phrases such as ‘From that day on…’ which is where we find the bit with the mandatory new situation. (All stories require a new-equilibrium — it’s just usually more subtle in stories for adults.)

From that day on, Mademoiselle Verity Brulée and Trixie Twinkle Toes eagerly read the weather pages — and if it was raining … they went out … with all the other dogs.

In an earlier age, children’s stories were often tied up a bit too nicely, resulting in a twee conclusion. Modern readers have less tolerance for this, perhaps because we can no longer buy anyone’s version of a ‘perfect world’, so we are told on the final page that Twinkle Toes and Verity are still not fully eye-to-eye — after all, Verity still calls Trixie’s very embarrassing full name at the public park.

OTHER CHILDREN’S BOOKS FOR LOVERS OF SMALL DOGS

HAIRY MACLARY FROM DONALDSON’S DAIRY BY LYNLEY DODD

WALKING YOUR HUMAN BY LIZ LEDDEN AND GABRIELLA PETRUSO

WHY DO DOGS SNIFF BOTTOMS? BY DAWN MCMILLAN, BERT SIGNAL AND ROSS KINNAIRD

As a New Zealander myself I can say this: Kiwis love toilet humour, and have a high tolerance for it in children’s literature. National pride.

GO DOG, GO! BY P.D. EASTMAN

DOGGIES BY SANDRA BOYNTON

PIG THE PUG BY AARON BLABEY

LET’S GET A PUP BY BOB GRAHAM

HARRY THE DIRTY DOG BY GENE ZION AND MARGARET BLOY GRAHAM

DOGGER BY SHIRLEY HUGHES

THE SHEEP PIG BY DICK KING SMITH

BECAUSE OF WINN DIXIE BY KATE DICAMILLO

THINGS YOU NEVER KNEW ABOUT DOGS

I LOVE DOGS BY EMMA DODD

100 DOGS BY MICHAEL WHAITE

PAWS BY KATE FOSTER

I WANT A DOG BY DAYAL KAUR KHALSA

SOME DOGS DO

THE GREAT DOG BOTTOM SWAP

MUTT DOG BY STEPHEN MICHAEL KING

DOG BY SHAUN TAN

DR DOG BY BABETTE COLE

THE CASE OF THE DISAPPEARING DOG

THE FENWAY AND HATTIE SERIES BY VICTORIA COE

OTHER POODLES