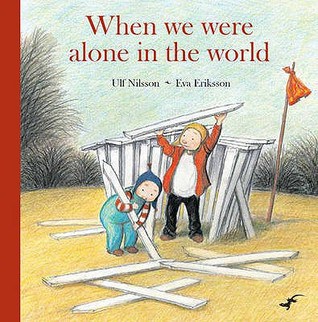

Written by author Ulf Nilsson and illustrated by Eva Eriksson, When We Were Alone In The World is a 2009 Swedish picture book produced by two longtime experts in their field. I am reading the English language translation from Gecko Press.

PLOT OF WHEN WE WERE ALONE IN THE WORLD

Written in first person point of view, a young narrator (probably a grown up by this stage) recalls the day he learnt to tell the time at school. He was five years old at the time and is looking back with knowing hindsight. The narrator is therefore extradiegetic, because hindsight has turned him into a ‘different character’ (for storytelling purposes).

On second reading, we notice the importance of the very first paragraph:

One day at school I learned to tell the time. Nine o’clock, ten o’clock, one o’clock, two o’clock.

Thinking it is three o’clock, the young narrator leaves school two hours early, wondering why his father isn’t there to pick him up. He quickly jumps to the conclusion that his parents must have been killed by a truck, and launches into parental mode, collecting his little brother from playschool, promising that everything will go on as usual despite the obvious tragedy. They walk home and build a makeshift house. Their sad, imaginative game continues until the parents turn up, having been contacted by the playschool.

WONDERFULNESS

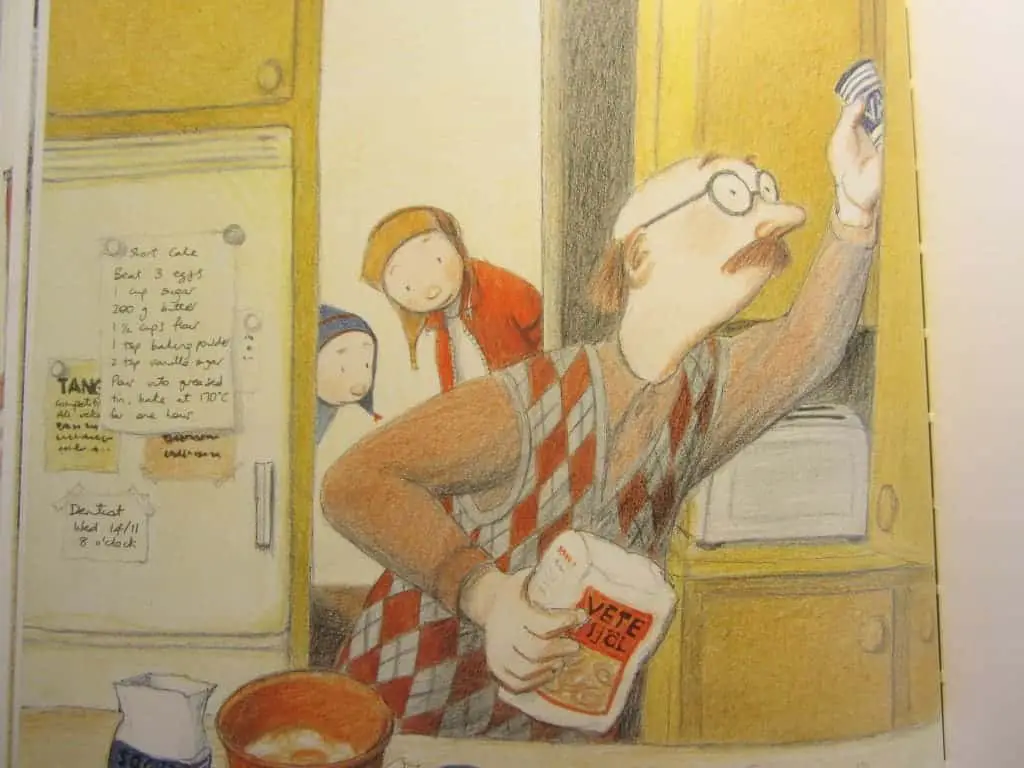

Translated beautifully in 2009 by Julia Marshall, something of the ‘foreignness’ has been retained in the English, but I can’t quite put my finger on what it is exactly. The European-ness is apparent on the cover, of course, as only the first letter of the title is capitalised. Some of the intratext has been translated, while in other cases the Swedish has been left in the illustration. This adds to the European feel of the story. For example, in one illustration, a recipe taped to the fridge has been translated into English but the packets of ingredients in the kitchen retain their Swedish names.

From Nilsson’s profile page at Bonnier Rights:

[Ulf Nilsson’s] books are filled with humour, warmth and imagination, often with a touch of irony (directed against himself). A theme always present is the victory of Good over Bad, and he always speaks in favour of children. Another theme is about acknowledgement and being seen, how to control your own fears by protecting someone smaller than yourself.

The illustrations consistently expand upon the words, creating dramatic irony for the reader. On the very first page we see the protagonist leaving school at ‘three o’clock’, but the illustrations show the other children still inside the classroom, pressed against the window. The close reader should be asking: Why aren’t all the other children outside, too? A close reader will notice he is carrying a paper clock but has left off the eleven and twelve. (The ten is even hidden by his hand.) The same paper clock is seen again on the second page, this time giving the reader a clearer view. In this way, small details are drip fed and slowly revealed over the course of the illustrations.

The imagination of the little boy will be familiar to all readers, the way the mind can jump to the worst possible conclusions when someone doesn’t turn up at the expected time. Unlike adults, who are able to employ reason, this story beautifully portrays the tendency for young children to both jump to the worst conclusion but at the same time turn their imagination over to a maudlin sort of game, funny and tragic in turn.

This funny/tragic juxtaposition is reproduced in the illustrations. While the words say that Mum and Dad got run over by a truck, the picture shows toddlers playing — some have spades in their mouths; the little brother is tipping sand over another child’s head. The maudlin humour is portrayed with phrases such as ‘We poor children’, and ‘It made me sad to think about them. My eyes filled with tears,’ and ‘The wind blew through the gaps in the rickety walls. It was such a shame about us.’ These are the words of a narrator who is self-aware of the humorous memory, without being heavy-handed about it. He is melodramatic and enjoys his melodramatic game on one level.

Young readers will definitely feel sad while empathising with the children. Adult readers will understand the humour from the start. This is how this masterful story achieves a dual audience. I really enjoy it as much as my six-year-old does.

Though trying his hardest to be a responsible grown-up, our five-year-old main character behaves as we might expect: The first thing he builds after returning home to an empty house is a ‘flagpole’. He finds a long stick and attaches a hanky. (Notice that there was a little red flag on top of the fort at playschool — surely this is where he got the idea — another hint at his naivety.) The whole house-building episode, in which the young narrator finds wooden fence posts and constructs a rickety shelter is surely a common form of play worldwide — playing house.

The humour of this scene reaches a new level when the young narrator goes next door to ask his neighbour for some eggs. He wants to make biscuits for the little brother, who normally eats a biscuit after playschool. The author introduces this scene with: ‘Then I remembered we could borrow things from our neighbour. Sometimes when you run out of something in the kitchen, you go over to a neighbour’s house and you borrow it.’ This is an important segue, because it tells the young reader that this is something that people do, but it also tells the adult reader that the young narrator has seen it done. Otherwise we might be wondering what provoked it. This sort of narration is worth a mention, I think, because it’s one of those techniques which is overlooked by the casual read — it is designed thus.

The list of requests for ingredients grows longer and longer, until the baffled neighbour has filled a bowl with every ingredient needed to make biscuits. The adult reader will identify with this neighbour, who is no doubt starting to wonder if the boys have been sent to him by the mother, as he may well have assumed! But he has been drawn so far into the boys’ game that he probably doesn’t know exactly how to stop.

Haven’t we all had the experience of interacting with a young child, wondering how much to believe, thinking there is probably some ‘truth’ to a story but not knowing exactly what? “The People Across The Canyon” by Margaret Millar is a short story for adults which delves into this exact problem.

In When We Were Alone In The World I like the choice of neighbour — an older man in a vest, who may or may not have much experience with very young children. (Matronly types may read the situation better!) We are not given any dialogue from the man — for all we know he questioned the boys, but the important thing is that he obliged. The boys mix everything together ‘using the antenna’. The choice to use ‘antenna’ instead of ‘stick’ is masterful — the children are now fully immersed in their own imaginative world. The stick is not a stick to them.

One thing I always love about young characters in picture books is when young characters draw on partially-understood adult experiences to recreate in their own imaginative play. ‘I didn’t know if we would be able to live in it when we grew up,’ the young narrator says, gazing upon the rickety, make-shift hut, ‘But we could build on eventually.’ I get the strong sense he has overheard adults talking about ‘building on’. This is particularly funny because the hut is so unstable, in which case the hut itself should be fixed, let alone ‘building on’. (The structure eventually falls over, at the very end, and we see a black bird sitting on top of it — a humorous symbol of death.) It is when the boys are in their parents’ arms that the hut falls over. Of course, it’s not just the hut which has fallen over; the entire imaginative role-playing game has collapsed. It’s time to return to the safety of reality.

The young narrator’s partial understanding of the world is echoed again when he makes a TV out of a carton found on the rubbish heap (‘It is quite hard to make a TV.’) and ‘a remote control from a smaller box’. When the TV won’t turn on he concludes it’s because the remote is out of batteries. Yet he knows he needs an antenna, and makes one out of a stick. Again we have a juxtaposition between the five-year-old boy knowing all sorts of things about the world, but with knowledge that stops short of actually making sense of it. ‘Anyway there’s nothing good on TV these days,’ he says, looking at the screen. ‘I sounded just like Dad and I rubbed my chin just like he did.’ The masterful phrase here is ‘these days’. A five-year-old can’t possibly have enough experience of the world past and present to use a phrase like ‘these days’, which is why it’s so funny, and reminds me of my six-year-old who reprimanded me for washing her stuffed toy, since she had been cuddling it a lot and working on its smell ‘for ten years’.

When the young narrator pulls carrots out of the ground, noting that his little brother ‘didn’t think much of them’, the reader sees from the picture that the carrots themselves are tiny, with lots of shoots growing off them — inedible, in other words. Again, this is letting the illustrator shoulder some of the work.

How to make sure the reader understands the story? The reader must understand by the story’s end that the reason the young narrator went home early is because he failed to tell the time correctly. The opportunity for this explanation is taken when the parents piece together what has happened, with the mother showing the boy that there are twelve numbers on her watch, not ten. There’s something about this story which makes me think it may be based on a true event. True or not, it definitely achieves that feel.

The final sentence of the story is ‘My little brother burped.’ With a description of a mildly funny physiological event, the reader is reminded that we are firmly in reality now, that nothing is all that important: This afternoon was just a ‘burp/bump/blip’ in the larger tapestry of life.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

The faces on the characters are simple, with dots for eyes and single strokes for mouths. This allows any young (white) reader to imagine that this highly stylised face might just as easily belong to him.

The drawings look to be rendered in coloured pencil, which usually lends a naive touch to picture books, since this is a medium commonly utilised by young readers themselves. The foreground shapes look to be outlined in ink (or strong, sharp pencil perhaps) which adds definition. Sometimes, pencil drawings can have a dream-like quality.

Adding to the naive quality, perspective is ever so slightly ‘off’ in some drawings — this gives a hand-drawn look in an era in which photorealism can be achieved reasonably easily using digital software.

The colour palette is warm — reds and browns dominate each page, and there is no obvious change of palette for the ‘scary’ pages or anything like that. The season looks to be autumn — the sky looks a little thunderous; the little boys wear winter hats. This is an autumn palette.

The end papers are a wallpaper of clocks, each showing a different time. “What?” my six-year-old said, when I asked her to read one of the clocks. “This isn’t a book on how to tell the time!” But here’s the thing: It can be a book about telling the time. The adult reader can point out that there are twelve hours in a day, not ten, for instance.

STORY SPECS

This is a squarish book in shape. Approximately half of the pages contain white space with the text as a separate asset; the other half are full page illustrations with any text overlaid. The text is a simple Times New Roman sort of font with a large ‘O’ to kick off the story.

Ulf Nilsson is a well-known Swedish children’s book author with over 100 publications under his belt.

Eva Eriksson has illustrated for a number of well-known Swedish series such as The Eddie Series (Eddieserien) written by Viveca Lärn about a boy in early elementary school age in Sweden. She also illustrated the Max Series by Barbro Lindgren, the Mimmi series and a series about a wild baby.

COMPARE WITH

By the very same creators, All the dear little animals is another book about death and loss incorporated into childhood play. This one is just as good as When we were alone in the world. This book is published both by Gecko Press (New Zealand) and Hawthorne Press (UK). There is a strong Christian undertone to this story. Apparently Ulf Nilsson takes a strong interest in Christianity and is makes a study of it without being Christian himself, which makes for an interesting juxtaposition. Gecko Press specialises in translating foreign picturebooks into English.

There is something endearing about stories in which siblings do something really nice for each other. In When we were all alone in the world, the older brother vows to look after his younger brother. The Charlie and Lola series is good on the sibling-harmony front, as well as the classic Dogger written and illustrated by Shirley Hughes, in which a big sister does something really kind for her little brother after he loses his pet dog.