Two Summers by John Heffernan and Freya Blackwood is a sobering Australian picture book about farming during drought.

I have a special interest in stories about drought (due to the fact I’ve written one myself). Perhaps because of this, I’ve given thought to ‘subject matter for young readers’ and ‘picturebook endings‘ and ‘juvenile capacity for melancholy’ and things like that.

WONDERFULNESS OF TWO SUMMERS

This picture book is an interesting example of sad subject matter dealt with through the lens of a pragmatic child narrator who is only beginning to get a sense of the magnitude of the problem of farm life during down years. See also the way this book ends with a sense of hope — the unwritten rule of publishing books for children which sell.

SENSE OF AUSTRALIA

If it’s not clear from the illustrations (which could be set in parts of America, I suppose), the second page of the story makes reference to coming off a bike due to a wombat hole — a specifically Australian problem, I suspect. The Australian setting is integral to the story rather than just a backdrop; though drought happens in other countries, it affects different places in slightly different ways. The language is specifically Australasian: ‘He won’t even notice how crook the place looks’, ‘poddy lambs’ and so on. This book will particularly appeal to readers whose extraliterary experience includes farming.

SENSE OF FOREBODING

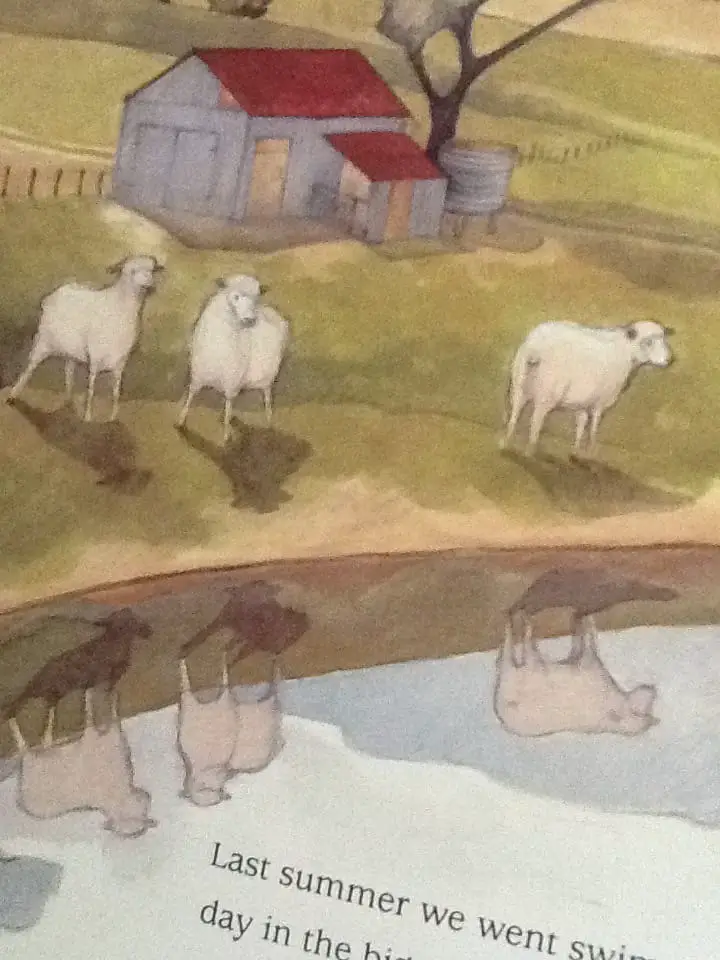

The book is split into two distinct parts; the first is the narrator remembering how much fun he and Rick had on the farm last year. In his memories, the landscape is green. The story changes at the page which reads ‘Dad says Rick will be in for a bit of a shock.’ We’re not told why; instead we’re invited to infer for ourselves what has happened. The water hole is empty, with the dingy resting on dry banks. There is no green, and the sky looks smokey blue, as if fires are burning nearby.

‘I don’t think we’ll have much trouble at the river this year,’ we’re told, in typical Australian litotes, because we can see there is very little water left in it, making it easy to cross. We can see the ribs on the cows.

THE NUMBER TWO

The title of this book serves as one signal to the reader about the treatment of time in this story. In stories, time can be indicated only by reference. In picturebooks time might be represented by changing light as the day fades, or with clocks and calendars or seasonal changes or ageing characters. But mostly in picturebooks, the passing of time is underscored by words, and in this case, by the title. The concept of two different summers is also conveyed by the ironic distance between words and illustration; while the young narrator describes how wonderful things were last summer, the reader sees from the illustration how dry the landscape looks, and how cows are dead on the ground.

With the title Two Summers the number can be riffed on in a number of ways, and Freya Blackwood has run with this in some of her illustrations:

- Two boys, one a country boy, the other from the city

- Two different farm experiences: one visit during a good year, another visit during a dry one.

- Two eggs in the eagle’s nest

- When the boys swim in the river the ‘camera’ is set low so that the surface of the water dissects the page (above and below water), in which two fish swim along with two boys

- The following page is a long, landscape shot. The house and the windpump are positioned on the page as almost a mirror reflection of each other.

- Next we have a scene where cows cross the river; two dogs stand on either side of the river; one looks hopefully across the water whereas the other has already crossed, and is sniffing at a dead cow on the other side.

- ‘Last year we rode round the heifers twice a day’

- On another page, two calves dip their heads into two feeding buckets; two boys each feed two poddy lambs

- On the page after that we see two dead cows (one with a calf), also in mirror image to each other. The layout of the pages employ the technique of (near) symmetry.

- Next we have another page dissected, this time by a strip of white for word placement, with a scene of cow branding at the top and a scene of lamb marking at the bottom.

- On the final page we see a scene of the narrator and his dog, which is a sort-of mirror image of the very first page, in which we see the same scene but from the other side. The dog on the first page is in the process of stealing the boy’s sandwich; now he is licking the plate. By mirroring the initial scene, the story is brought to a satisfying close, though in the world of the story, the visit from the cousin(?) is about to begin. The reader’s end = the narrator’s real beginning.

SYMBOLISM IN TWO SUMMERS

What does the sandwich/dog/plate symbolise? The boy presumably goes hungry — is he hungry for just this one meal? Is he feeding his dog in the same way he feeds the poddy farm animals? To continue in maudlin fashion, if drought were to continue, eventually we’d all be losing food. The dog on the final page looks happy, presumably because he lives in blissful ignorance, much as this narrator did last summer.

With a dead cow on one side of the river, the river itself forms a kind of dissection. In stories rivers can symbolise many different things — often they symbolise a journey, but more negatively can also signal an irreversible passing of time. On this page I feel the river signifies a division (between two different life experiences — one of plenitude, the other of meagre pickings, much like the river in The Three Billy Goats Gruff.)

EUPHEMISM

There are lots of poddies. Ewes just walked away from their lambs this year.

Foxes and crows took some. Mum and I grabbed the rest.

The narrative voice feels detached and pragmatic, but it is clear from the story exactly what is happening. The word ‘die’ is avoided, and not just because this is a picture book and therefore for young readers; this is the way farmers talk.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION OF TWO SUMMERS

The colour palette is very much of the Australian landscape.

Freya Blackwood is particularly skilled at drawing from a bird’s eye view, and does so here on numerous pages to show a great variety of things going on in the farm scenes, but also to convey a sense of helplessness, as if these people are like ants, small in their environment, and at is mercy.

WHO IS THE TRUE PROTAGONIST OF TWO SUMMERS?

This is an interesting question because the unnamed narrator (it’s significant that he’s unnamed) functions a little like a ‘storyteller as character’ — we know that he’s a farm boy, but we actually end up knowing a lot more about Rick — his injuries, his struggles, his character arc (how he gets better at riding a bike and so on). If this weren’t a picture book, we wouldn’t have a picture of him at all. Red-headed Rick’s position as central character is solidified when we consider what Mercedes Gaffron called the ‘glance curve’.

the “glance curve” … moves from the left foreground back around the picture space to the right background. Because we look first at the left foreground, we tend to place ourselves in that position and to identify with the objects or figures located there … People represented here belong to our side in the figurative sense of the term, in contrast to the people on the right side“. In fact, the protagonists of many picture books … do tend to appear on the left more often than not.

Nodelman

Sure enough, if you flip through this book with rules of the Western Glance Curve in mind, you’ll see that Rick has been positioned by the illustrator in ‘protagonist position’ — more often than not he is the character we see first.

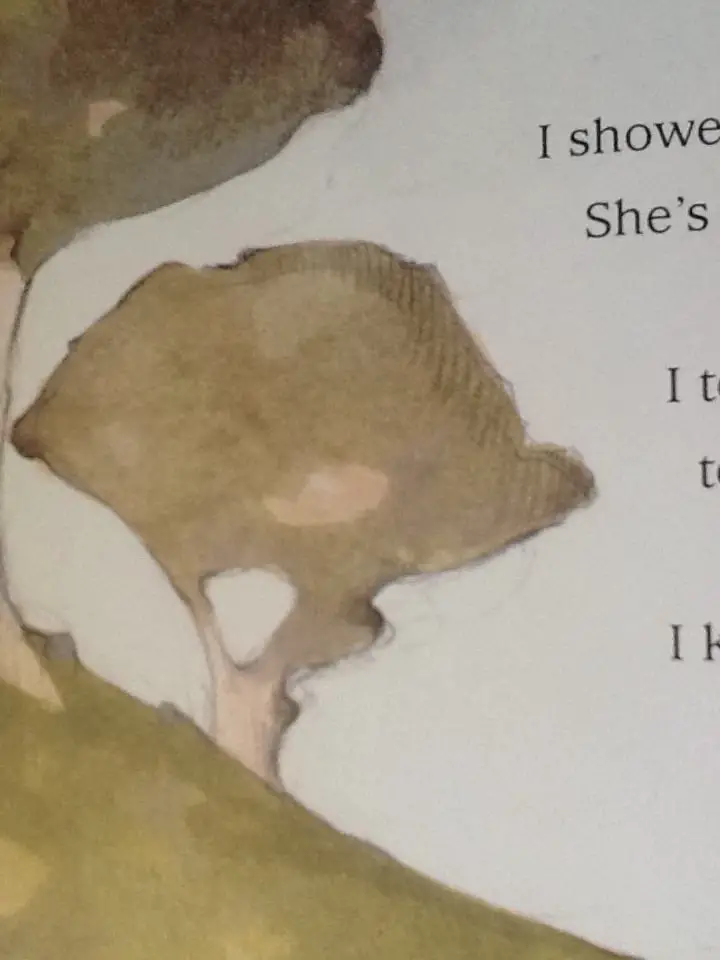

DRAWING THE SPACES BETWEEN

Comparing this art style to something like Thirteen O’Clock illustrated by Tom Barling in the 1970s, in which every leaf of every tree is defined in detail (giving the book a distinctively 1970s look), Blackwood’s approach to painting objects in the distance seems to be ‘draw the spaces between’, as art teachers are sometimes known to advise. Take a look at Blackwood’s trees:

THE ENDING OF TWO SUMMERS

The sense of hope achieved on the final page is backed up by the colour of the sky on the final page — for the first time we’re given a sense that it might indeed rain, with a darkening sky. This could be read in two ways, of course — dark colours in picture books can also convey a sense of foreboding.

STORY SPECS OF TWO SUMMERS

Published 2003 by Scholastic Press

John Heffernan has written about thirty books for a range of audiences from early readers to young adults, in a range of genre that includes realistic fiction, fantasy, futuristic, and picture books. He also writes for junior readers under the pseudonym “Charlie Carter” (most notably, the Battle Boy series).

Booked Out

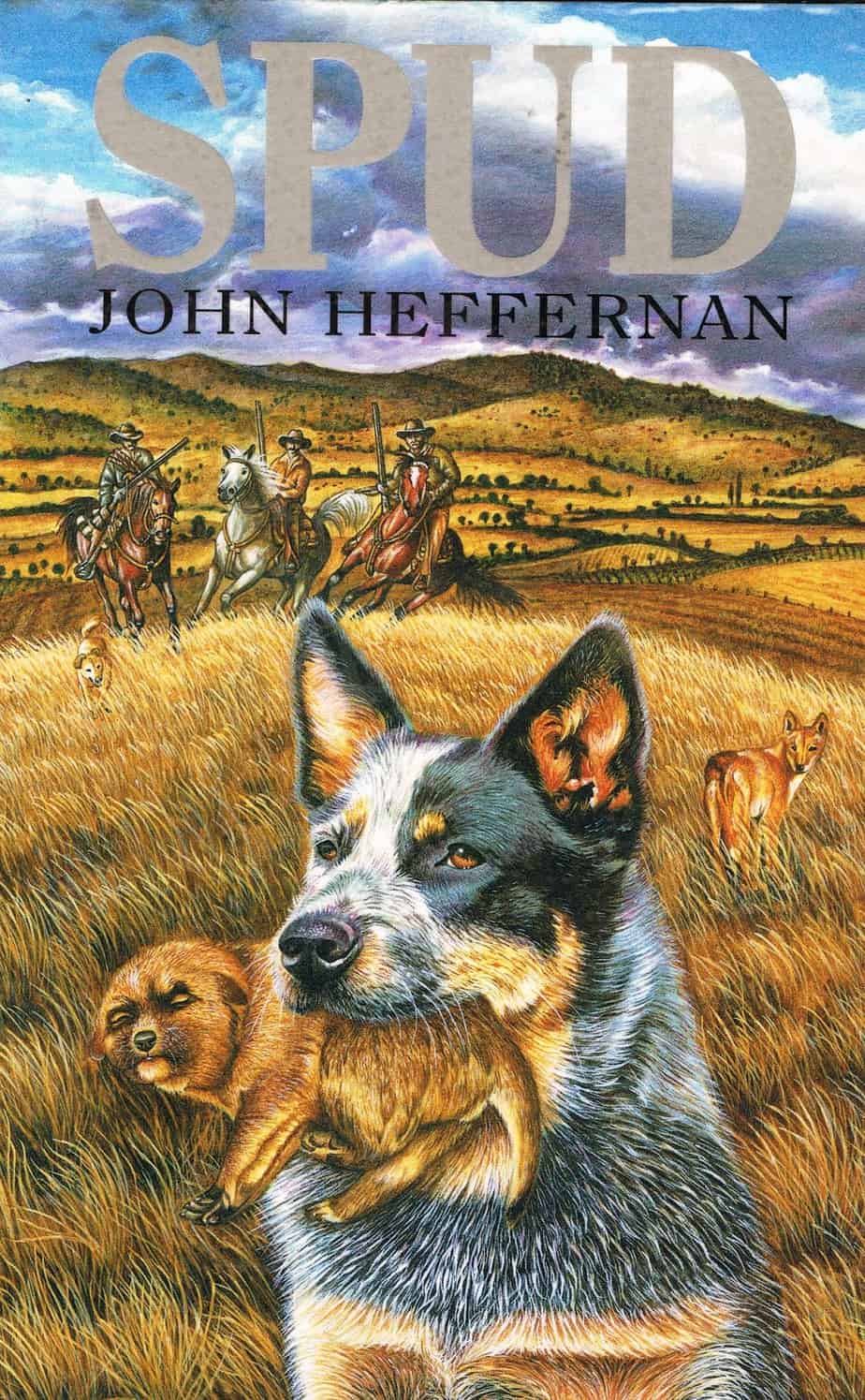

This dramatic and compelling tale of a blue heeler will touch the hearts of all readers. John Heffernan’s vivid portrayal of life in the bush is written from first-hand experience. Spud is the author’s own loyal companion on his property in northern New South Wales and was the inspiration for the story.

Spud is the first book in the popular series by award-winning author John Heffernan. Look out for the other best-selling titles, Pup and Chips.

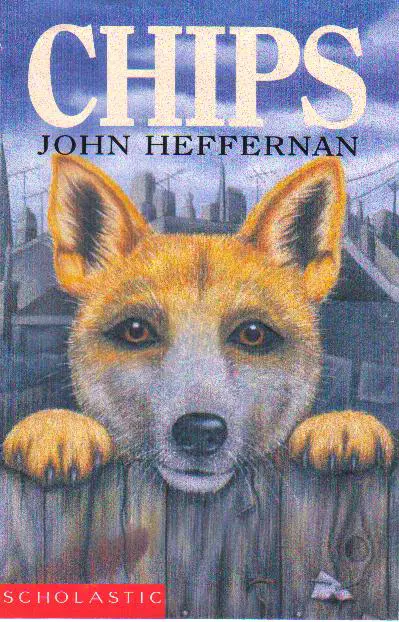

Chips is half dingo. He is Spud’s only surviving puppy, saved from a cruel death. A new life in the city with Kylie and her mother promises safety for them all. But as Chips grows, his wild dingo blood begins to stir and he hears a call he cannot resist…

This moving and powerful book is the sequel to Spud , which was not only highly successful, but also a Children’s Book Council of Australia Notable Book.

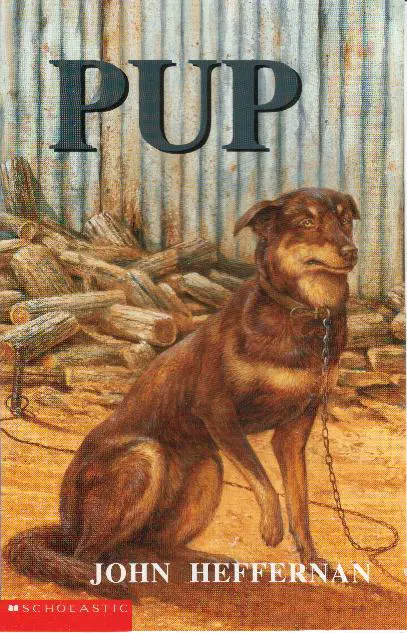

Pup is the only dog left on the farm when Kylie and her mother leave, taking Spud and Chips with them. He is very lonely. Worse still, he alone now has to bear the full weight of Jim Morton’s anger and cruelty.

The kelpie had once been a happy, energetic, fun-loving work-dog. But his love of life is being slowly beaten out of him by the man who shouts and screams. The young dog simply must escape if he is to survive.

He does escape, and embarks on a whole new life with a young boy called Jack.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

There is such a thing as a ‘storybook farm’. I’m thinking of board books in which toddlers learn the names of different farm animals. The farm animals have personalities. This storybook farm I’m imagining is probably set in America (not in a drought year), and there will be big American barns, almost always red. Do you have many of these books on your shelf? In picture books, the farm is often a kind of utopia, and will have the following:

- the importance of a particular setting (in farm books, a farm)

- autonomy of felicitous space from the rest of the world

- a general sense of harmony

- a special significance of home

- absence of the repressive aspects of civilisation such as money, labor, law or government

- absence of death and sexuality

- and finally, as a result, a general sense of innocence

The Year At Maple Hill Farm by Alice and Martin Provensen is a counter example of a storybook farm. The Provensens remind the reader over and over that although the seasons feel harsh to humans, the animals don’t struggle at all.

The artwork of The Year At Maple Hill Farm is more reminiscent of the folk-art illustrations by Pat Hutchins, most famous for Rosie’s Walk.

Rosie’s Walk is one kind of farm utopia, because no harm comes to Rosie — as sorry as we may feel for the poor fox, we don’t assume he starves to death — he probably catches her later, off-screen!

WRITE YOUR OWN BASED ON TWO SUMMERS

Obviously, ‘storybook farms‘ as seen in picturebooks are not real. What other storybook setting might you depict in more realistic fashion, while retaining some sense of hope at the end?

How might you take a most-usually American setting (a yellow school bus, an elementary school) or a white-nuclear-family setting and make it more mimetic of real life?