The Three Little Pigs is one of the handful of classic tales audiences are expected to know. Pigs are handy characters: They can be adorable or they can be evil. You can strip them butt naked and let the reader revel in their uncanny resemblance to humans. Or, you can dress them in jumpers and they’re as cute as kittens.

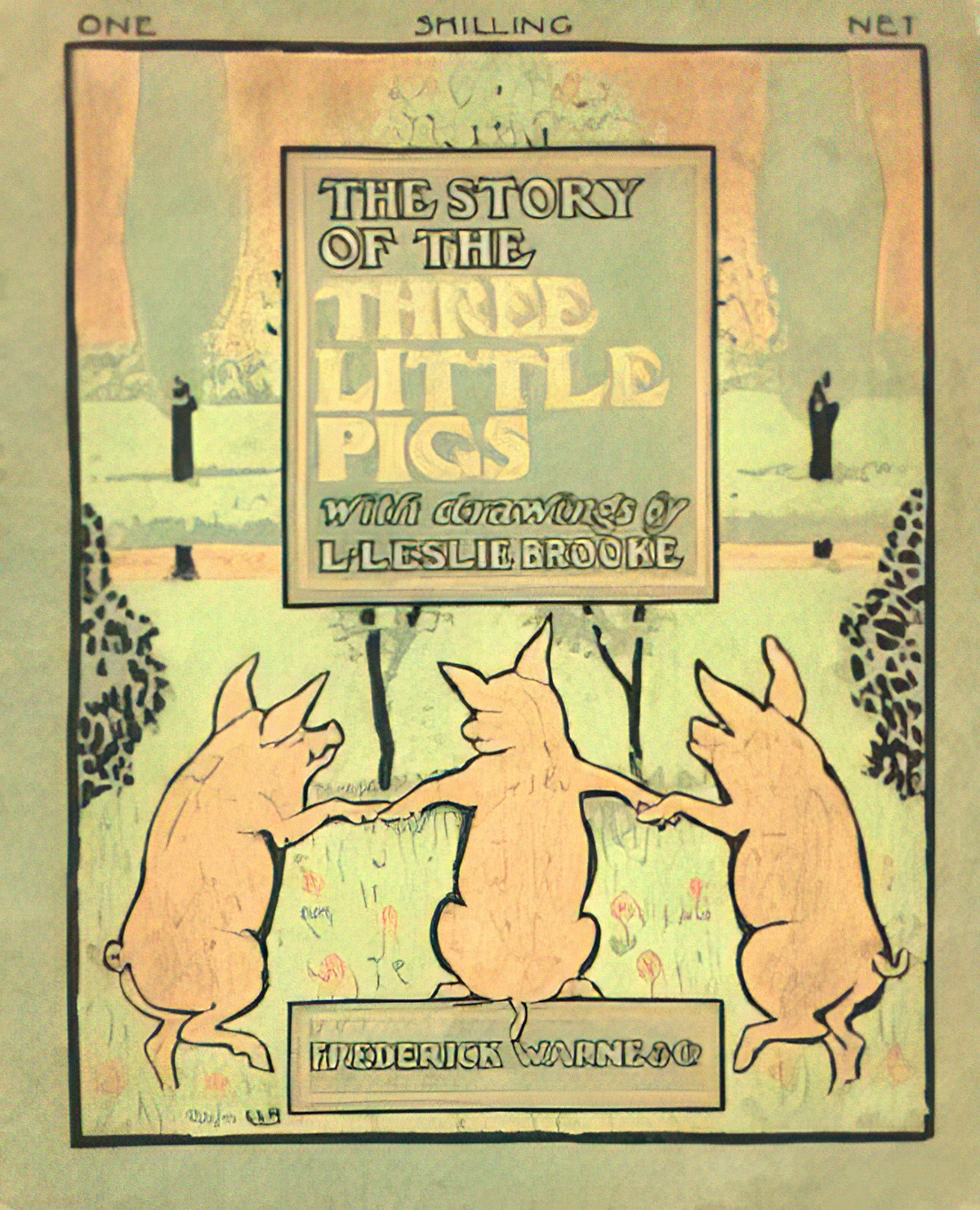

Brooke’s version of The Three Little Pigs, published January 1st 1905 by Frederick Warne and Company, is out of copyright and available at Project Gutenberg.

No one knows who wrote it, but we do know it’s from England.

This version is also part of the Mother Goose collection.

(Did you know that children’s books in general originally emerged from nursery rhymes and folk tale? And that William Godwin, husband of Mary Wollstonecraft and father of Mary Shelley, published the first Mother Goose Tales?)

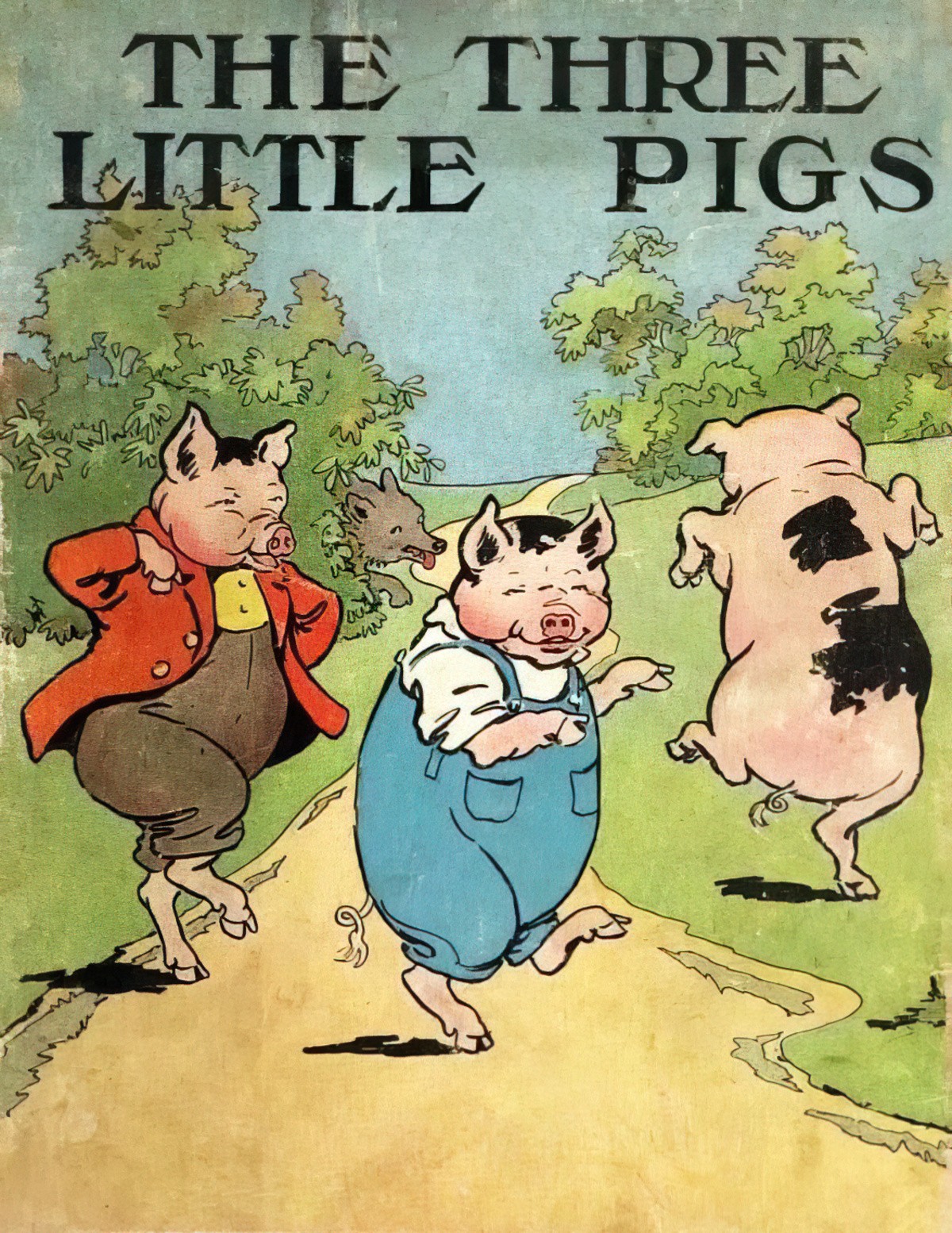

In the edition below the Three Little Pigs are given names: Spotty, Curly-tail and Little Runt. By giving the pigs names, and also by dressing them in clothes, storytellers make the pigs more sympathetic to human readers.

Giving previously unnamed fairytale characters personal names is a trick normally employed by the Disney corporation. (The dwarves of Snow White didn’t have names until Disney named them.)

NAKED DANCING PIGS

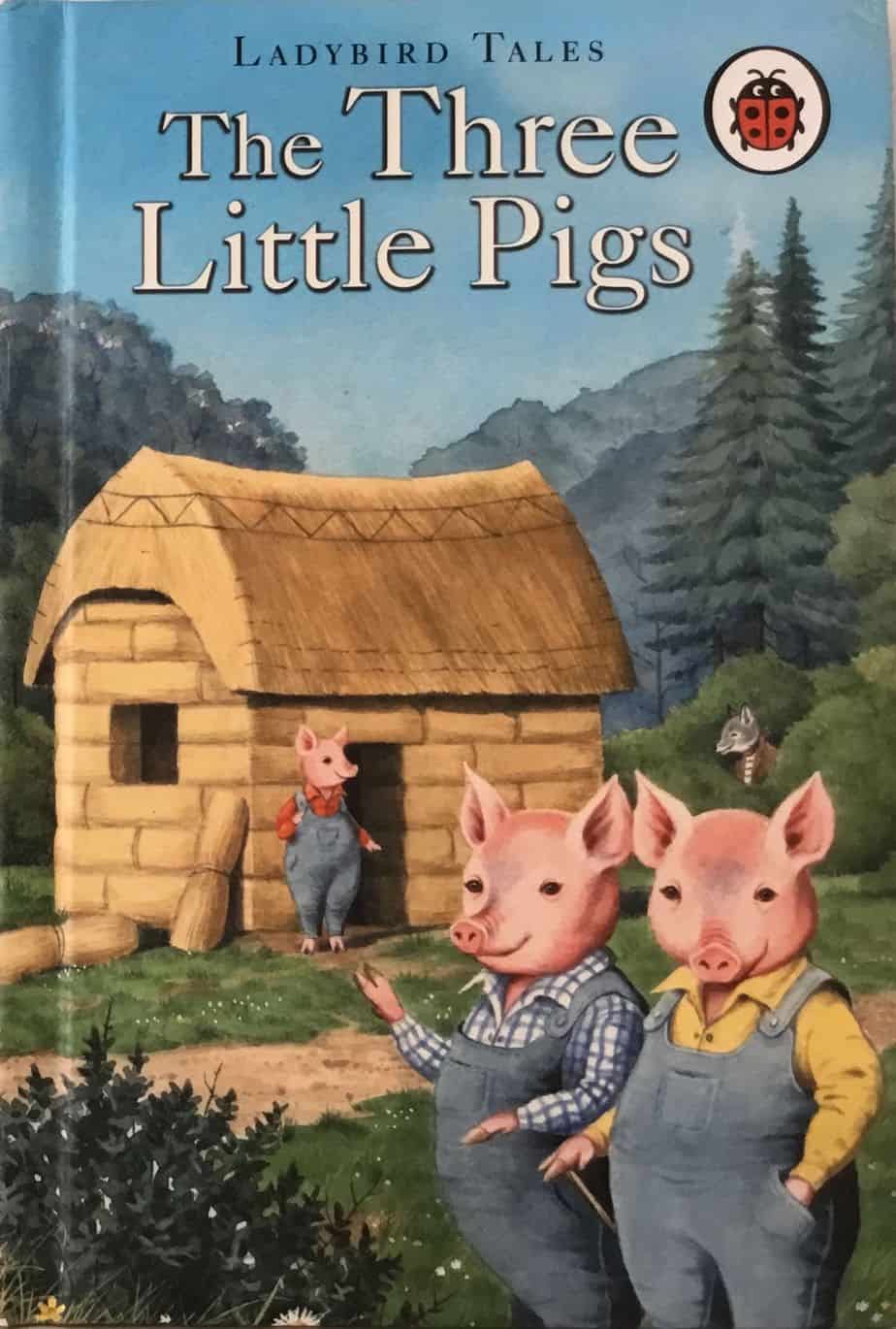

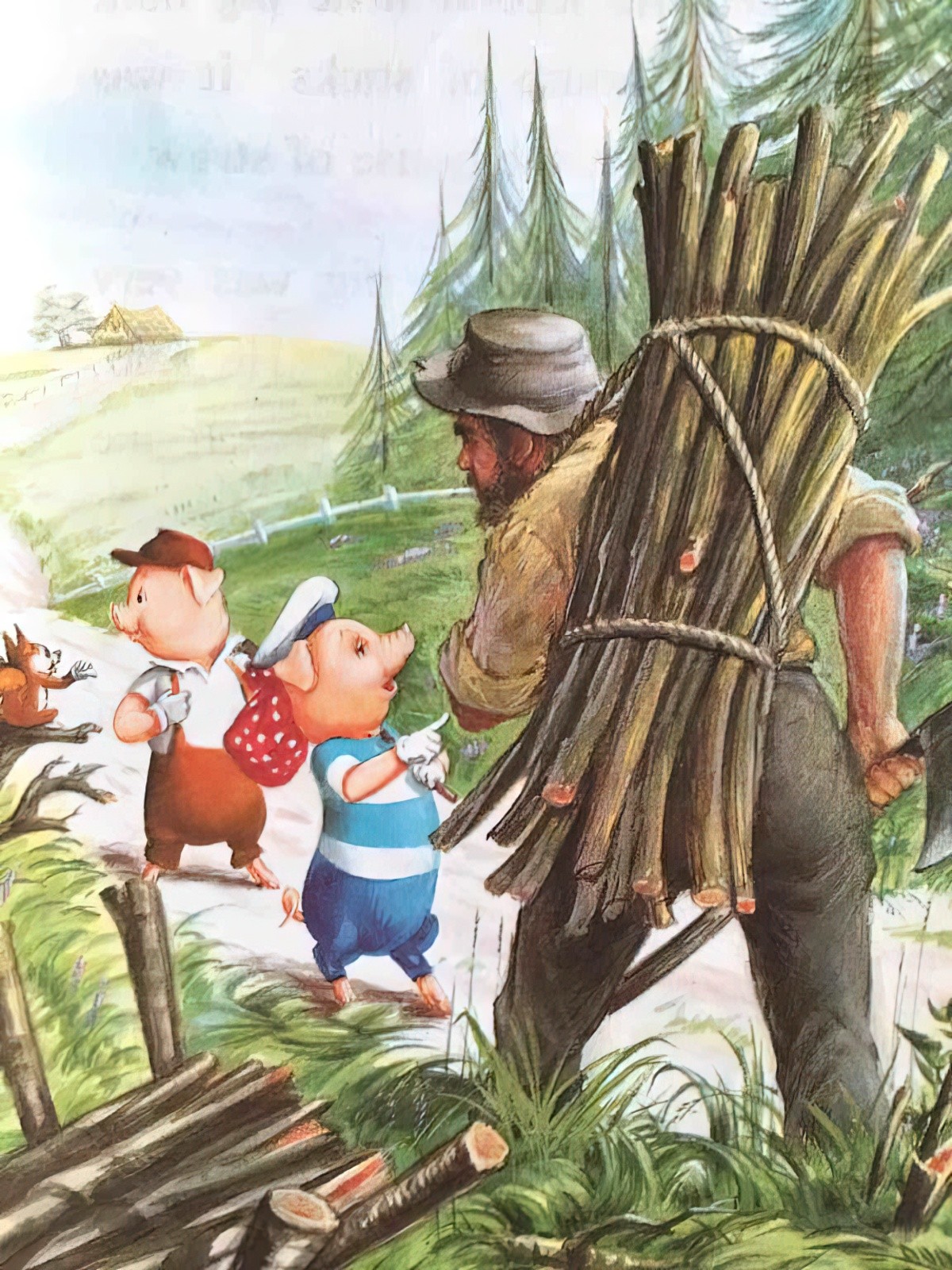

Margaret Blount, in Animal Land, points out that in this version, the animals are not yet wearing clothes. It was only after Beatrix Potter that animals started to wear clothes in picturebooks.

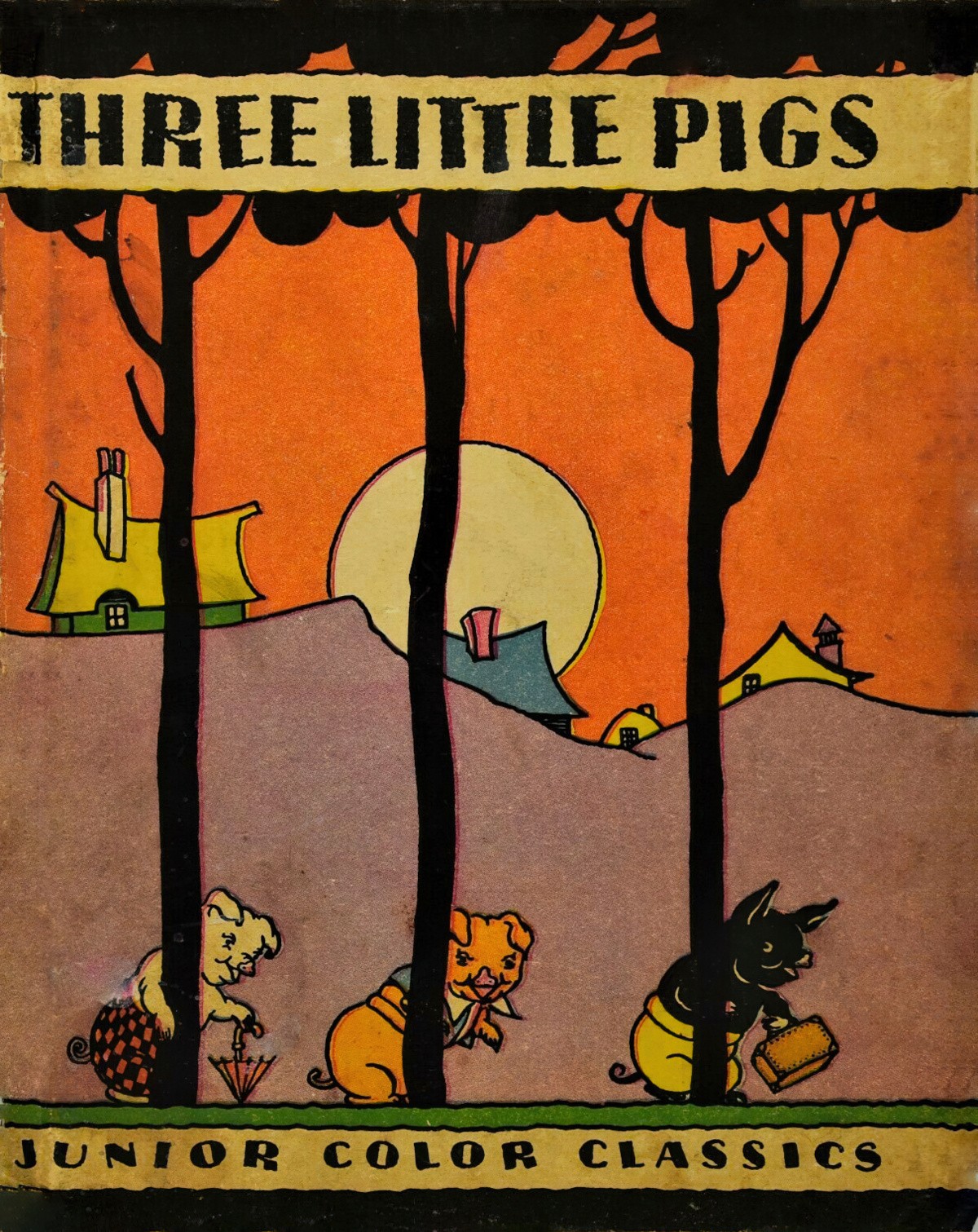

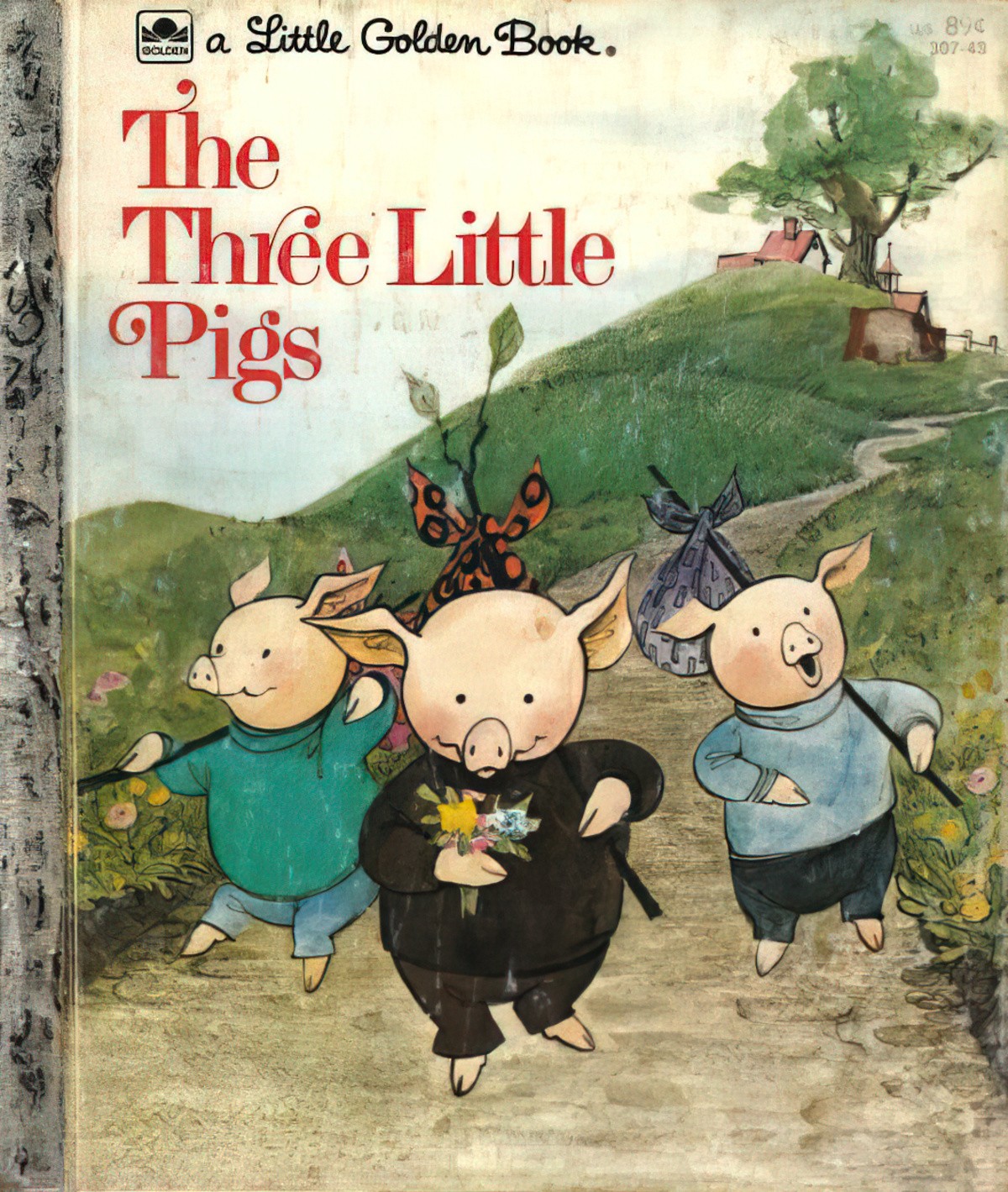

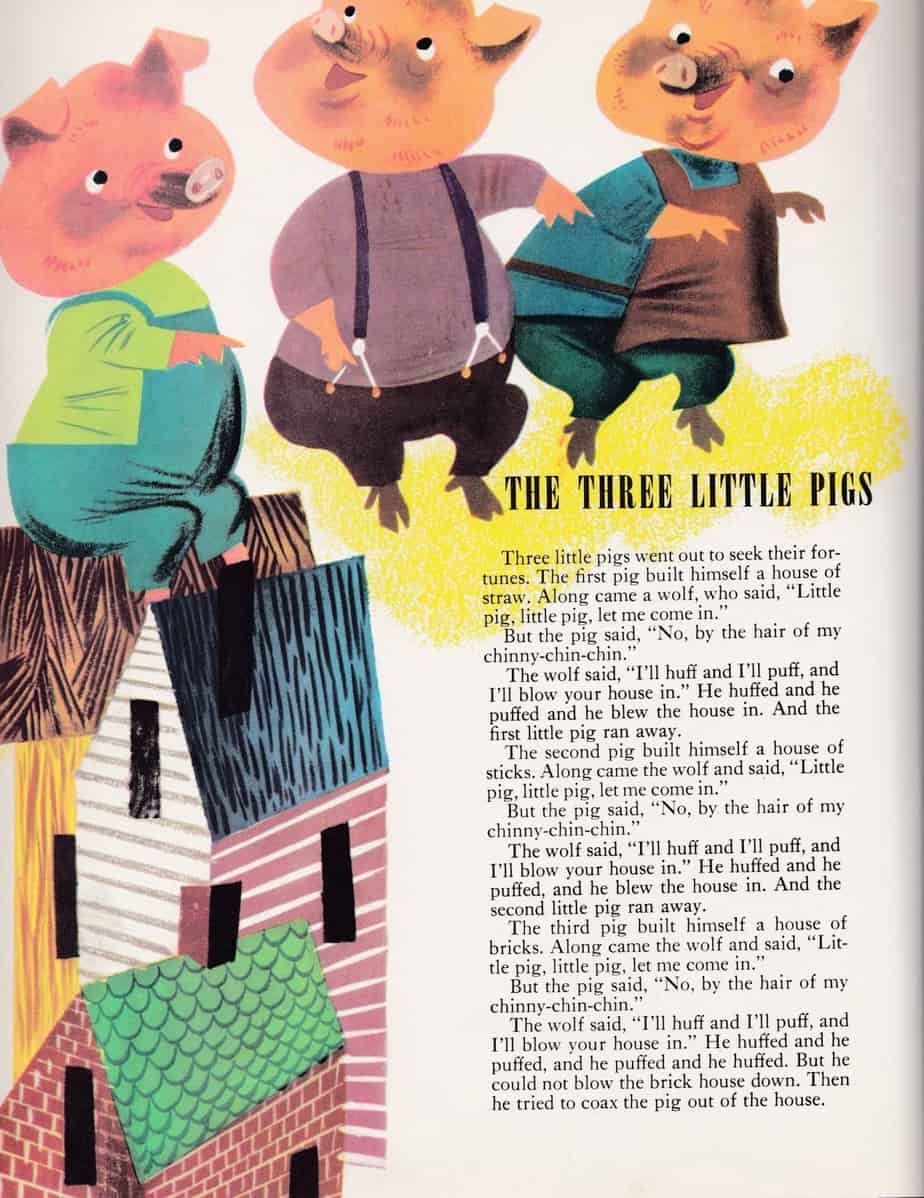

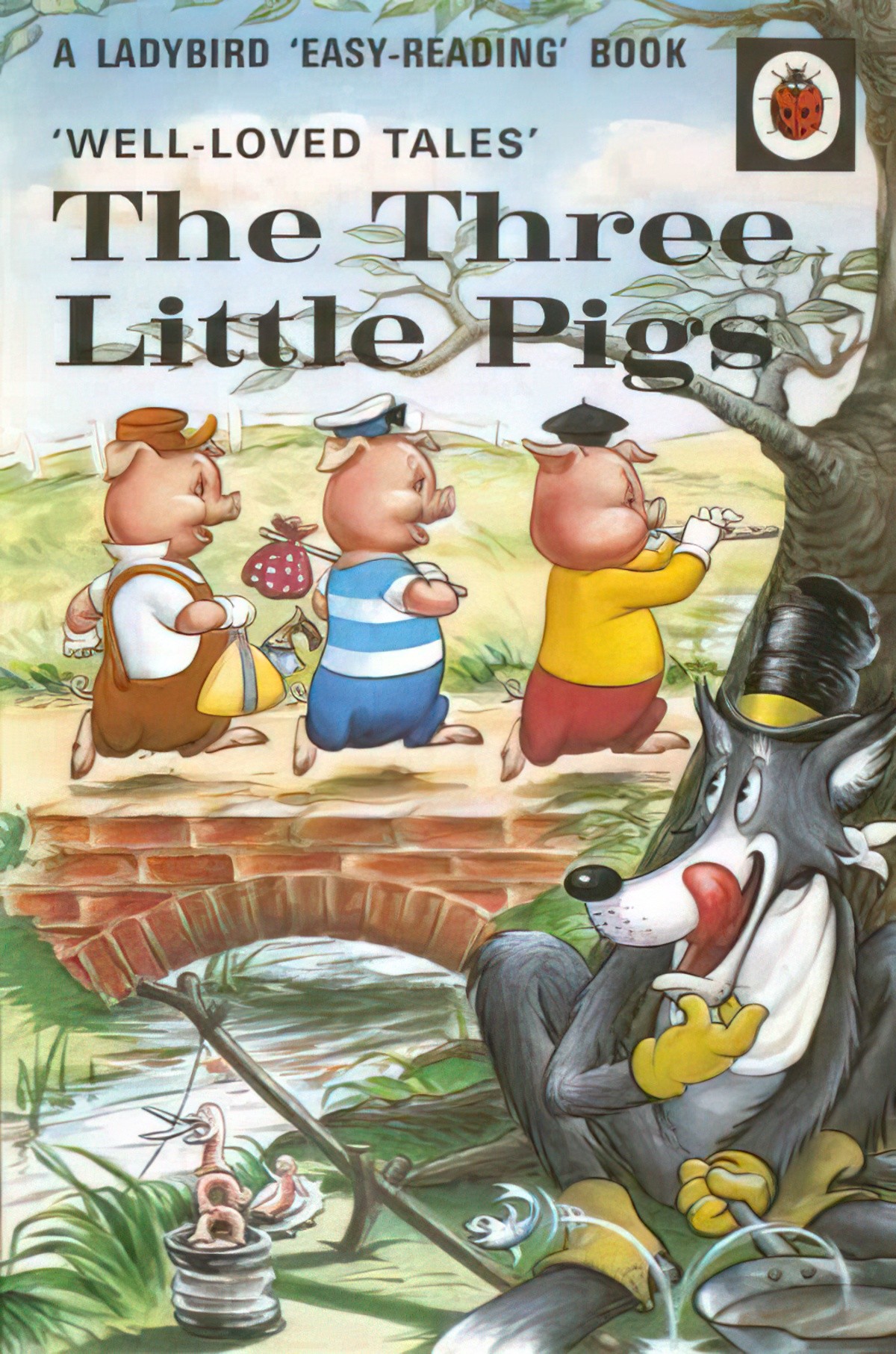

There were several different versions of this tale in my house when we were coming up — this was my favourite. It has very 1970s art and as you can see the pigs are wearing clothes. Though it’s not obvious from the cover, one of the pigs is carrying a bundle tied with a pink kerchief. Although gendered male in the text, I asked my eight-year-old if this pig was a boy or a girl and she said, “I don’t know.” She’s grown up in the pinkification of femininity, and to her, one pink item normally signifies a girl.

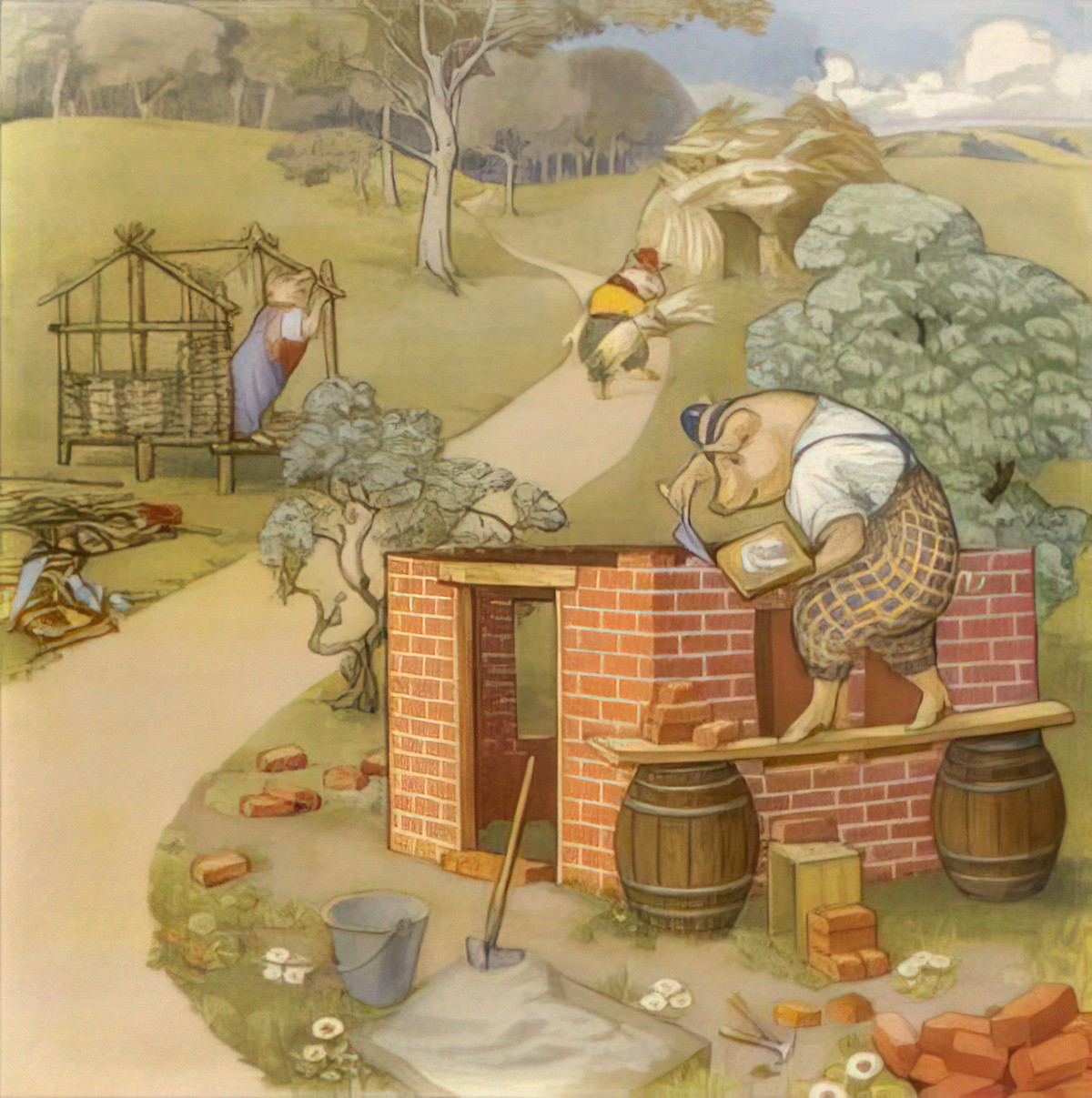

There was also this version from my childhood, and notice these ones aren’t wearing clothes. It’s harder to find naked pigs in this century, however. The newer Ladybird editions feature clothed pigs.

I grew up with the 1973 Little Golden Book of The Three Little Pigs, illustrated by someone who went by “ROFry”. I have no idea who this person is, but they seem to have also illustrated My Home and This Little Pony. The illustrations are beautiful, non-Disneyfied, and I would like to have seen more from them.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE THREE LITTLE PIGS”

The story of the Three Little Pigs has a mythic Odyssean structure, with characters leaving home to embark upon a journey. Sometimes these heroes return home afterwards; in other variations they find new homes.

Picture books about journeys tend to feature a road (or river) in at least one spread. The illustration by Mary Evans is especially masterful in its composition, including all three houses in one frame. Of course readers aren’t supposed to take away that the pigs were building their house this close together — it’s a ‘fantasy map’, conceptual rather than GPS accurate, much like maps you find from the medieval era.

As much as any fairytale ever written, The Three Little Pigs makes full use of the Rule of Three in storytelling.

Who is the main character? The main character is the one who changes the most psychologically over the course of the story. That doesn’t include changes in circumstances, such as from living to being dead.

Still, I will argue that fairytales work slightly differently. We’re working with tropes here rather than fully-rounded individuals, and although the smart little pig doesn’t really evolve over the course of the story — starting smart and staying that way — the smart pig is nevertheless painted as the viewpoint character, which gives him the edge.

That said, the illustrations in Brooke’s version humorously depict the smart pig as more sociopathic than the hapless wolf. Readers may find their sympathies divided, and my wolf-loving eight-year-old refuses to read fairytales which vilify wolves. (Hence she prefers The Three Little Wolves And The Big Bad Pig.)

SHORTCOMING

The two stupid (or lazy) brothers are dealt with swiftly, and in this version they get eaten. There’s no running away or anything, more typical of modern adaptations for the preschool set. We don’t actually see a gory blood and guts scene but we do see a satisfied wolf with his guts full of bacon.

The smart pig’s shortcoming is that he is delicious.

DESIRE

Surface desire: He wants to build a house.

Deeper desire: He wants to live a full life, safe from carnivorous wild animals.

OPPONENT

You could argue that the brothers are opponents to each other. In contrast to the goat brothers in The Three Billy Goats Gruff, these pig brothers are isolated from each other and show no cooperation.

The Big Bad Wolf in this tale is really no such thing. The audience already knows that the house of bricks will survive any big struggle, and Francis Spufford links it back to Piaget:

The invariability of a story is what gives it a secure existence. It adds it to the expanding sphere of what is known for sure; and therefore to the dependable world, which is made up at the deepest level, for a small child, of patterns on which it is safe to rely. Piaget called the patterns in an infant’s head ‘schemes’. They begin very simple. There is one scheme of ‘everything that will go into my mouth’. Then it subdivides, and there are separate schemes for food and for not-food. Complexity mounts up. Another way of seeing it is to say that small children agree intuitively with Wittgenstein. “The world is the totality of facts, not of things.” It’s what you know to be true that constitutes the world. Objects are terrible important, but the things in the small child’s world that she or he can touch — the red brick that somehow encapsulates the nature of the whole box of bricks, the kitchen furniture nested at the centre of the whole geography of home — count just as one type of true fact. Objects are just a subset of a scheme that has already divided, the scheme of things-that-are-true. They’re the type of fact you can verify by prodding or biting, but they go together with other types, equally certain, such as the fact that morning always comes. Or that the third little pig’s house will never blow down in any retelling of the story, no matter how hard the wolf huffs and puffs. Stories are so.

The Child That Books Built, Frances Spufford

PLAN

The pig is smart enough to realise the wolf is a trickster, so the pig outwits him in turn by getting up earlier and earlier. This is clearly one of those stories which position early risers as morally more upright than people with a circadian rhythm that runs later!

Again we see the rule of threes, with three attempts by the wolf to lure the smart pig out of his house of bricks:

- the turnips

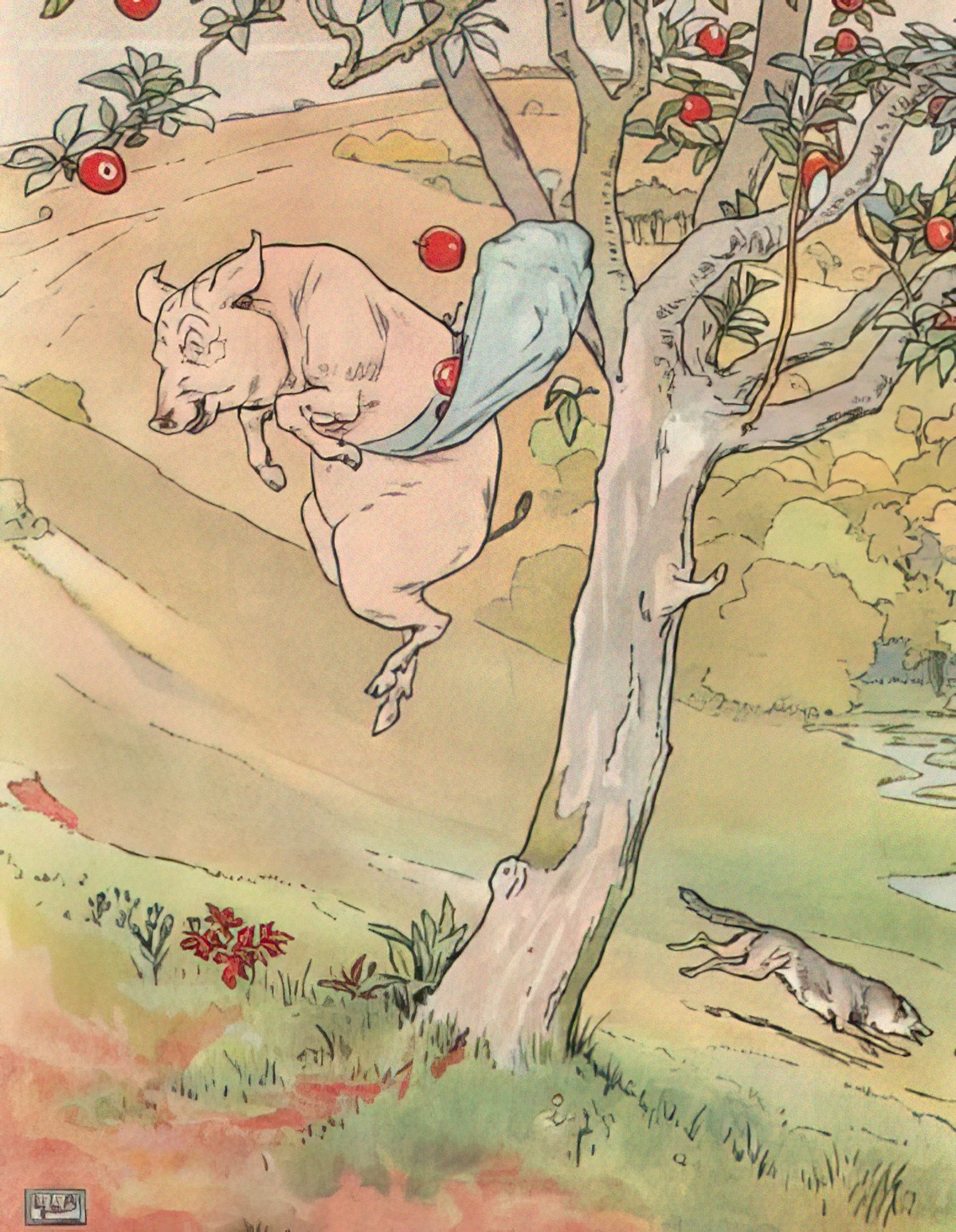

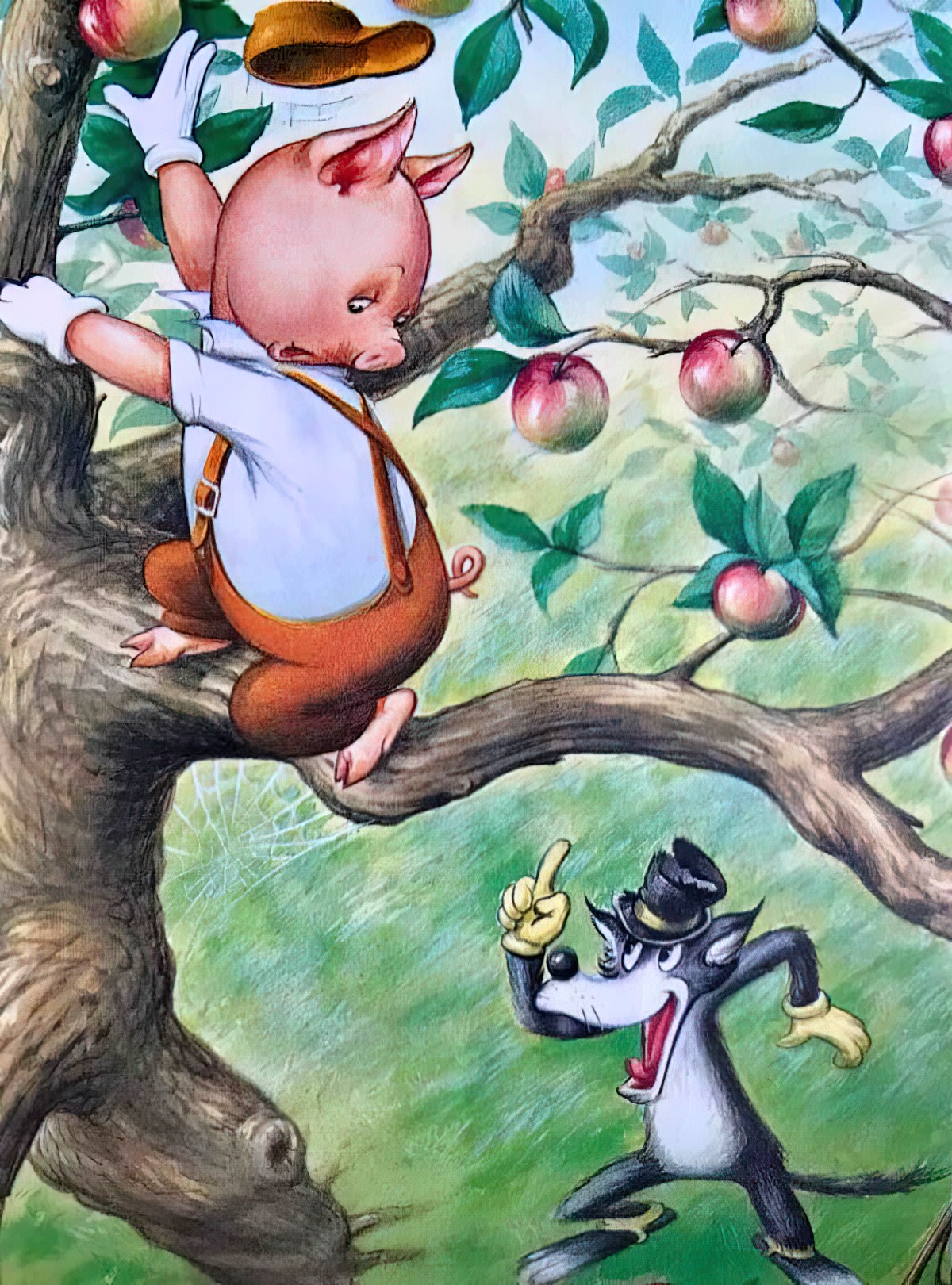

- the apple tree

- the fair

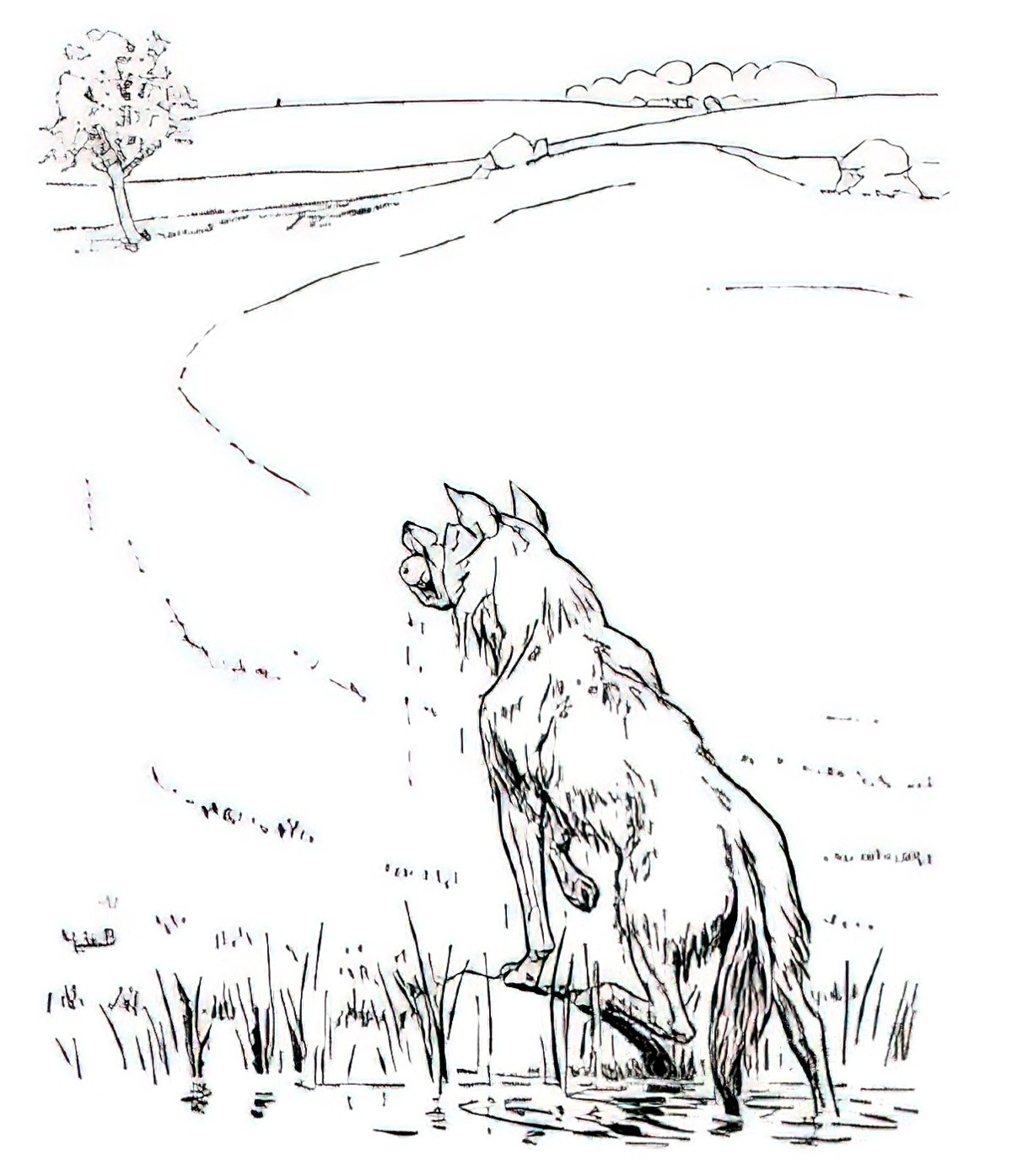

It is during this big struggle of wits that the audience sympathy is encouraged to switch from the pig to the wolf. In illustration this is achieved very simply by having the reader look over the wolf’s shoulder.

BIG STRUGGLE

The escalating struggle sequences contain a lot of humour, even in this gritty version. There’s something comical about the pig jumping from the tree. Is it partly because we have no idea how he get up there in the first place? Is it because the wolf is so oblivious to the jumping pig even though it’s happening right in front of him? Or could it simply be the sight of a naked anthropomorphised pig?

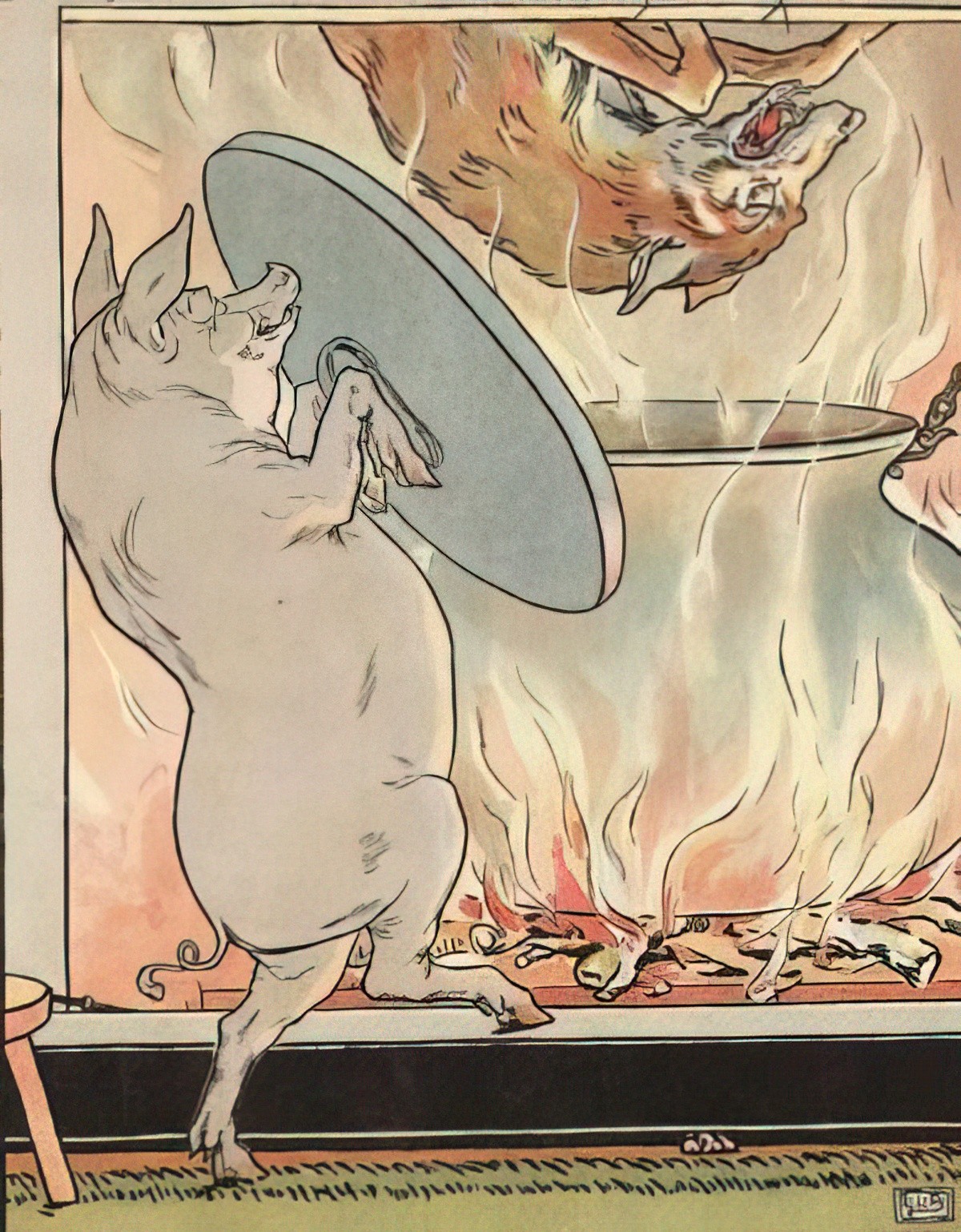

The pig in the butter churn is also funny — probably because his naked butt is showing, and the Big Bad Wolf is scared.

When I look at the video in the tweet below, I realise pigs might have a long history of being roly poly.

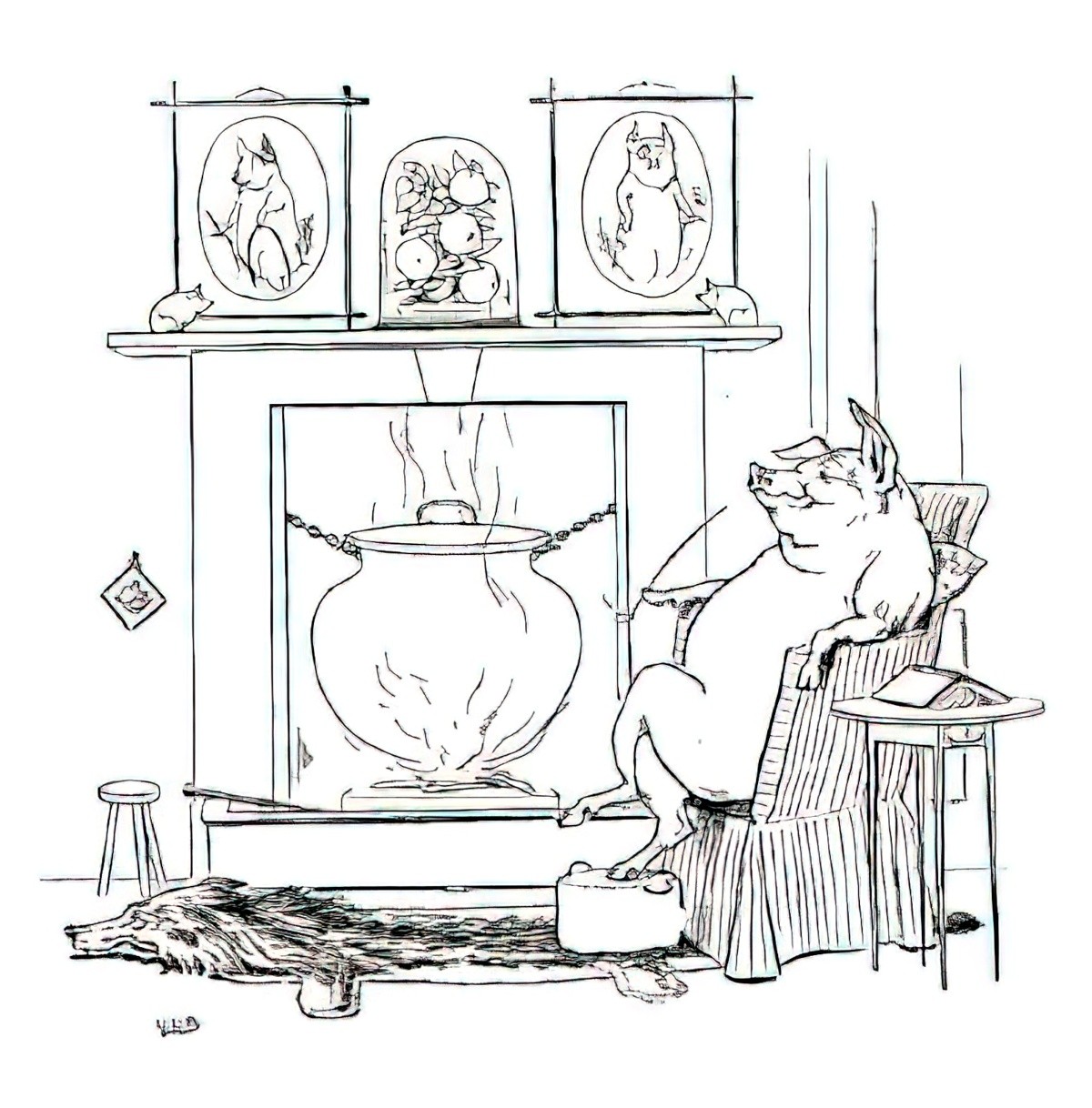

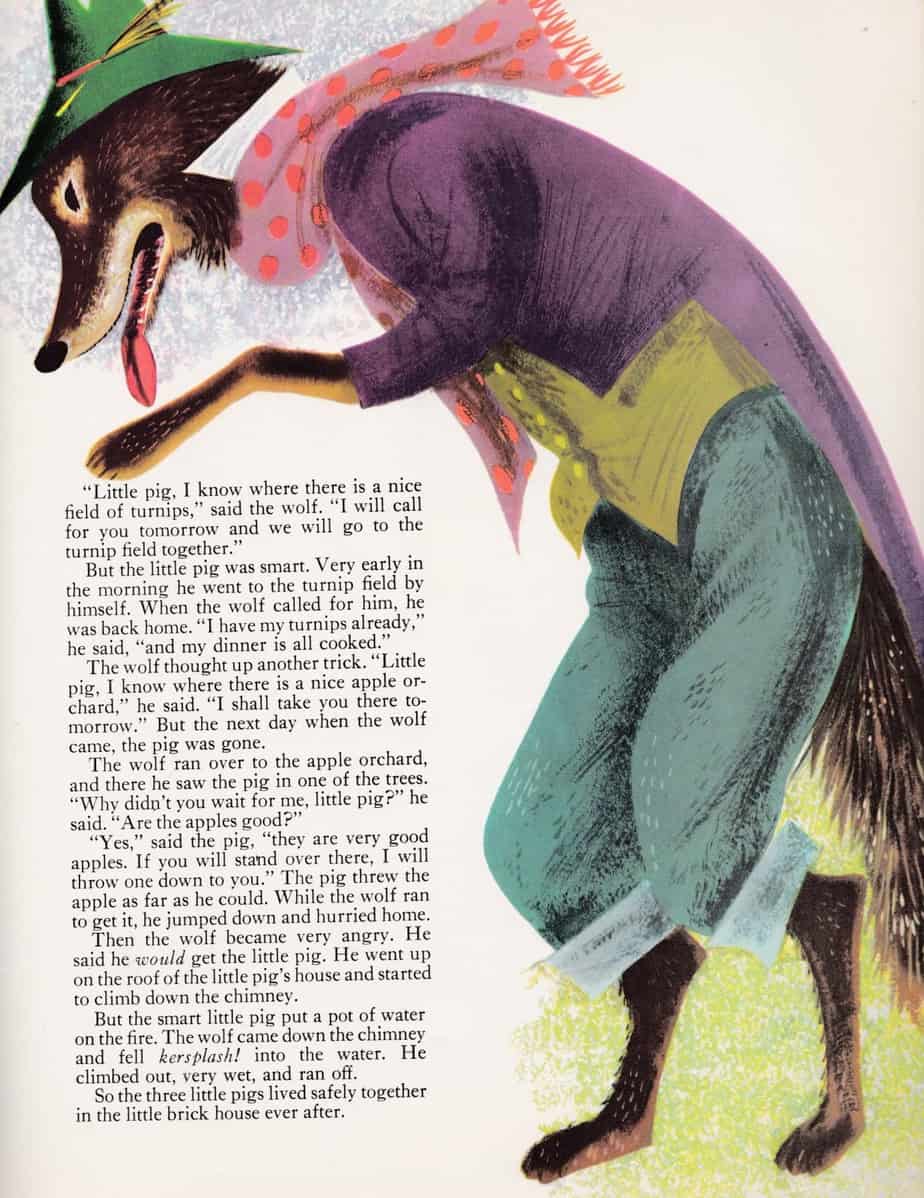

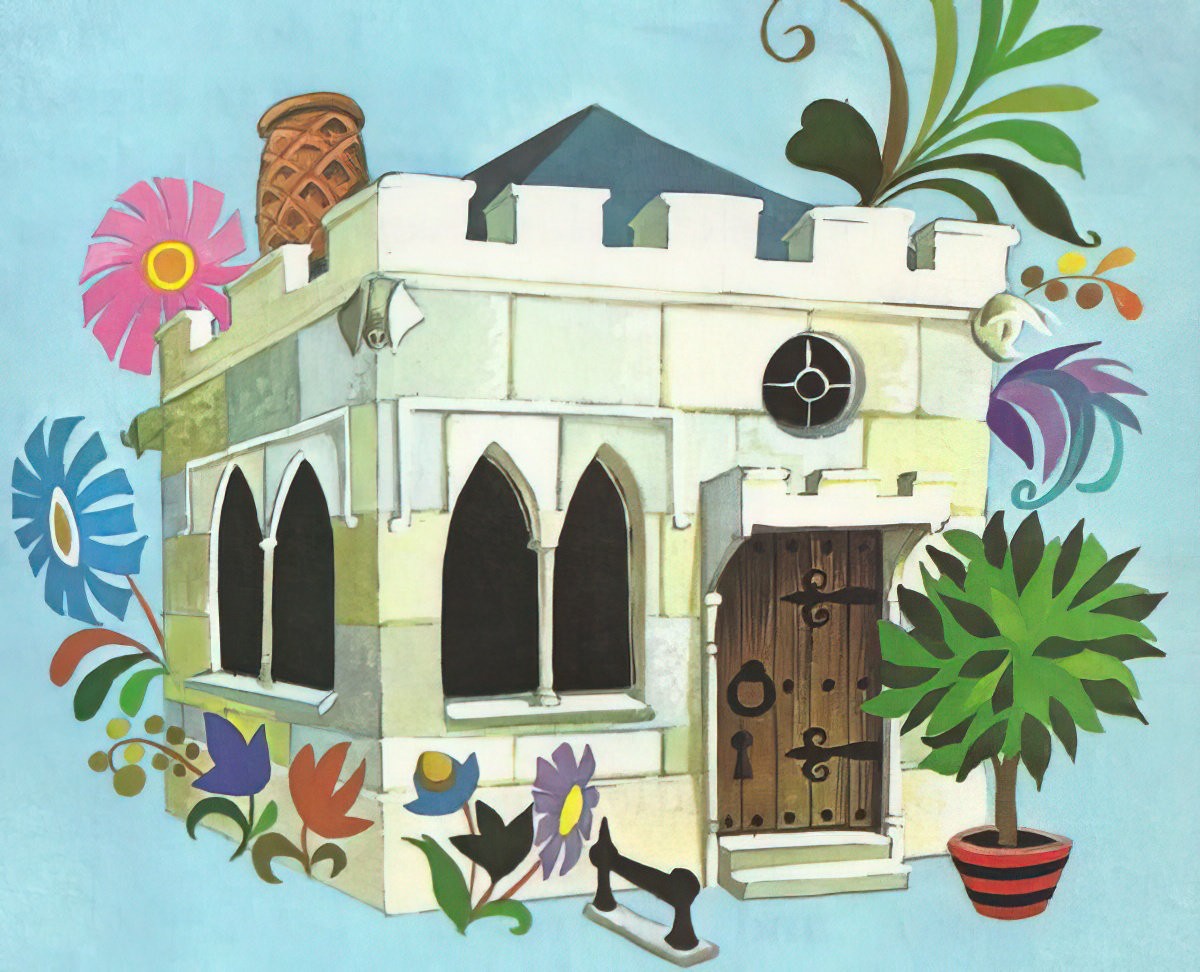

In this gritty 1905 version, the wolf falls down the chimney straight into a pot of stew.

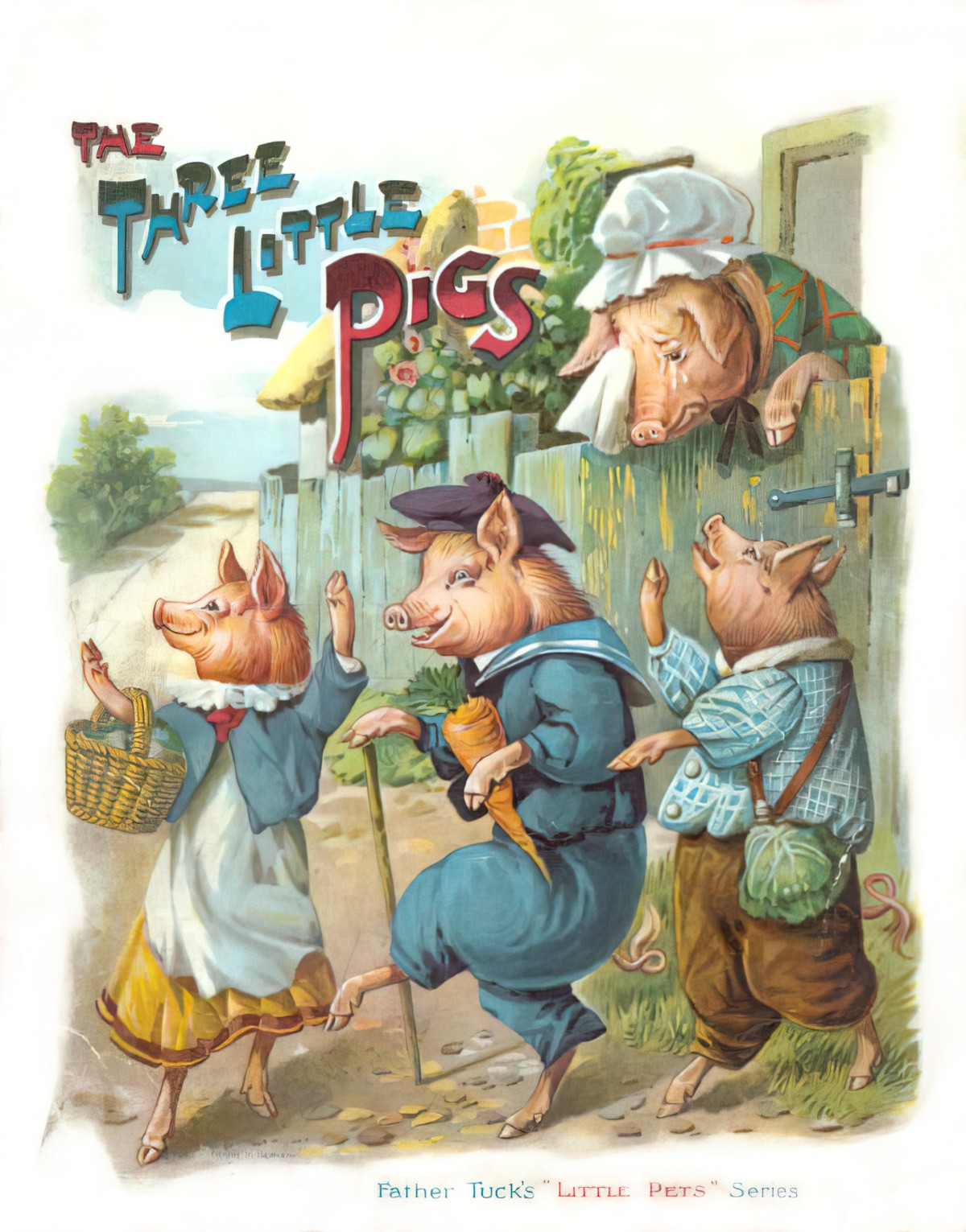

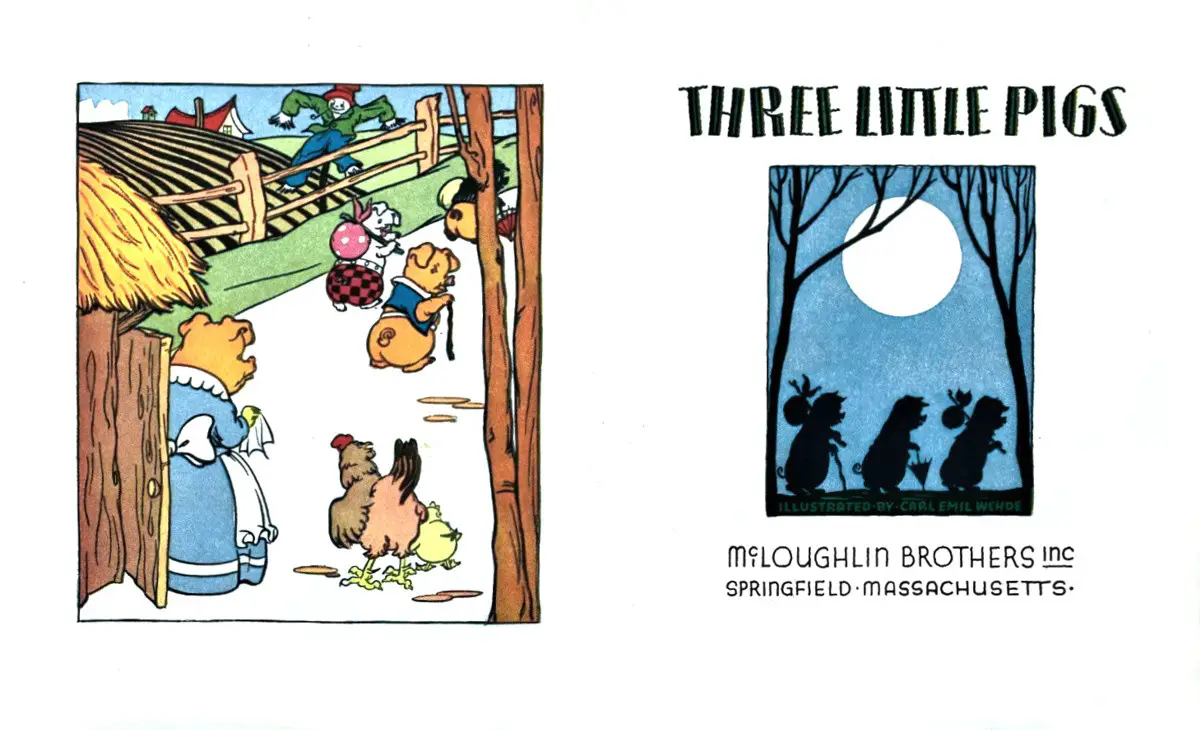

Modern editions for contemporary kids don’t make a meal out of this scene, but the Three Little Pigs story from Father Tuck’s “Mother Goose” series puts this image on the front cover. Sensibilities have changed. Not to mention, it’s normally an odd choice to ‘ruin the story’ by depicting the climactic scene on the front cover, which speaks, I think, to the fact everyone coming to this story already knows what happens.

ANAGNORISIS

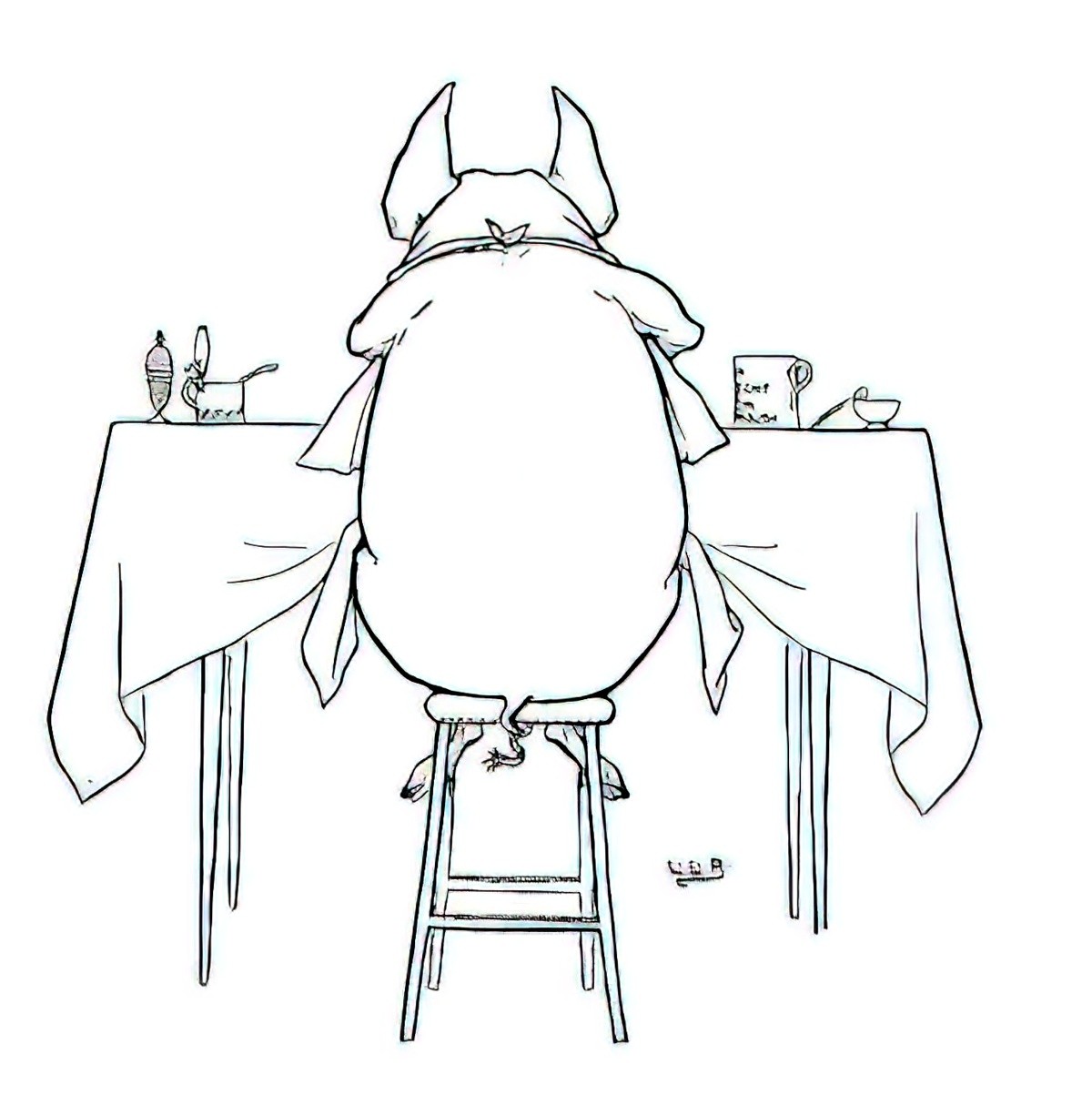

I’ve yet to see a pig actually eating the wolf but we come as close as we’re probably ever going to get with Brooke’s back view:

The revelation, perhaps, is that the pig is the genteel baddie and you should’ve been rooting for the wolf all along.

Or perhaps the young audience is simply reassured, having heard this same story many times before.

NEW SITUATION

The Wolf is cynical and worldly looking, and the last Pig sitting by the fire is like the satisfied man who has taken out a life-insurance policy — which, as the story is about prudence, is quite fitting.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

The Big Book of Nursery Tales retold by Evelyn Andreas illustrated by Leonard Weisgard (1954)

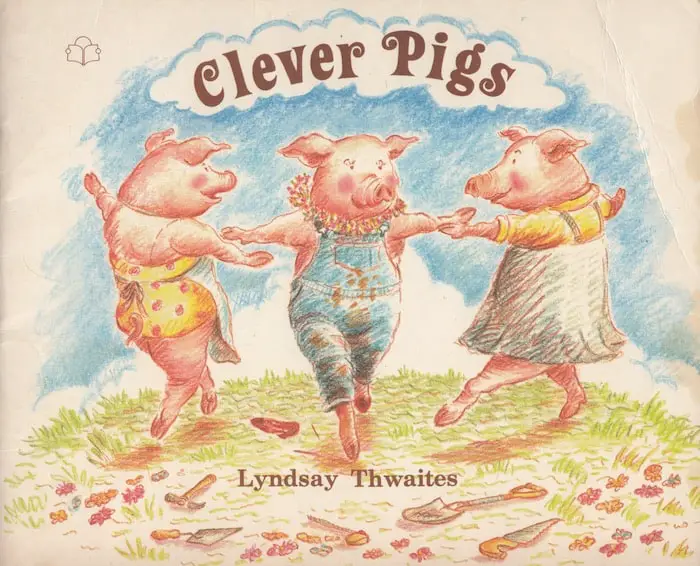

1980S FEMINIST RE-VISIONING: CLEVER PIGS BY LYNDSAY THWAITES

Like any classic tale, there have been numerous re-visionings over the years. Some are more successful than others. This is one from my childhood — hard to get a hold of now.

At first it looks like it’s a retelling of The Three Little Pigs, but it’s a story written on the back of second wave feminism, in which three female pigs each has a anagnorisis that she can do more than her fairytale trope.

Though the story is somewhat lacking due to lack of an opponent, it’s an example of the ‘battle-free myth form’ which we’ll probably see a lot more of in years to come given the success of Pixar’s Inside Out.

Unfortunately the batle-free myth form is really hard to do well, precisely because there’s no big bad wolf and no big big struggle scene.

STORY STRUCTURE OF CLEVER PIGS

SHORTCOMING

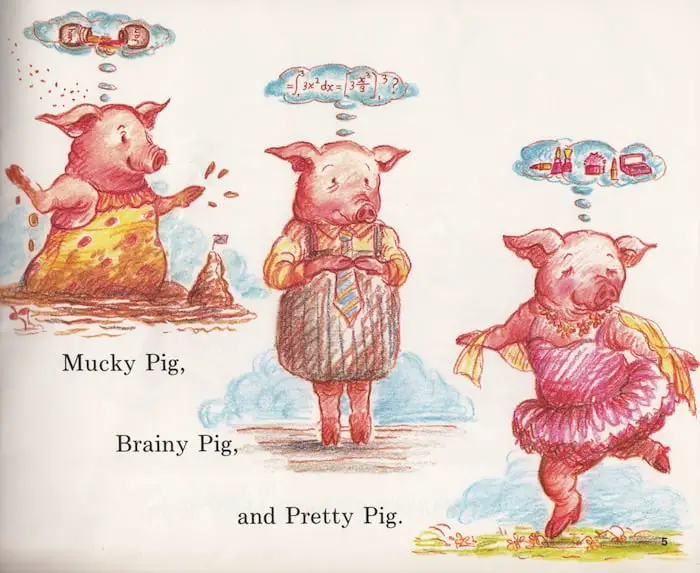

Each pig is introduced as a category, as in a fairytale. See also: Fairytale Archetypes. Except these aren’t archetypes from fairytales — they are the sort of labels that get attached to children fairly early on — the kind of labels that can be restrictive.

DESIRE

They lived in a rubbish dump where they were quite happy.

Emphasis is the author’s. The pretty pig is shown saying “Pooh!” but apart from that these pigs aren’t really driven to do much. They spend their days doing exactly what they supposedly like to do best.

OPPONENT

There is no opponent, except for the wider society who has decided that each pig is an archetype rather than a complex individual.

PLAN

There is no real plan.

BIG STRUGGLE

There is no big struggle.

ANAGNORISIS

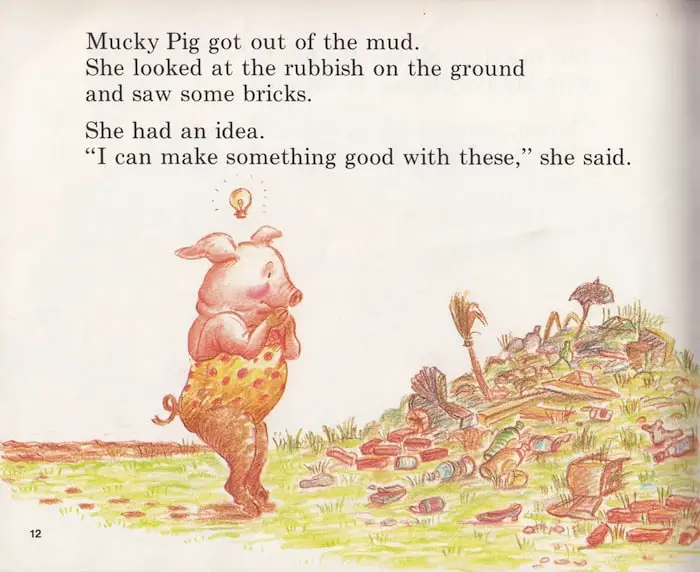

Instead, we skip straight to the anagnorisis.

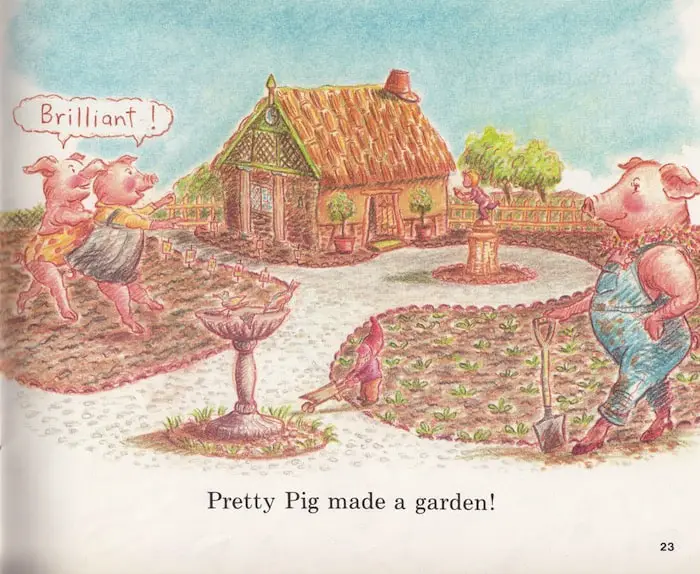

NEW SITUATION

From now on the pigs will not live in a smelly rubbish dump but in a pretty garden, because they were each able to diversify their skills. Presumably their new occupations better suit their true talents, which is how they were able to make a garden.

More illustrations from Father Tuck’s series

The Three Little Pigs illustrated by Robert Lumley, 1965

Janet and Anne Grahame-Johnstone

Interesting History

Take any fairy tale and you’ll find numerous versions. There’s a similar tale to this called The Fox and the Pixies. Pixies sounds similar to Pigsies. Could the pixies have turned into pigs at some point in the oral evolution of this tale?

Maybe!