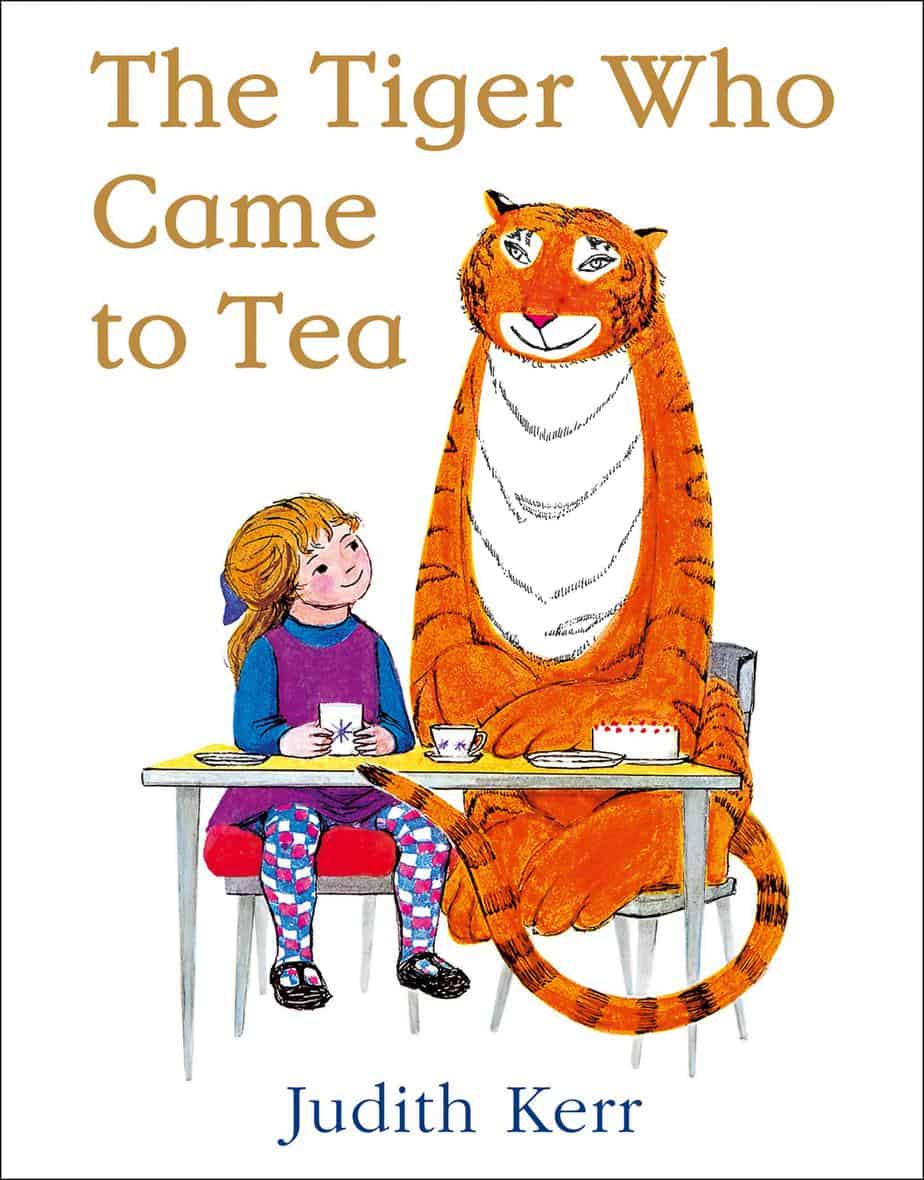

The Tiger Who Came To Tea (1968) is a picture book written and illustrated by British storyteller Judith Kerr.

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE TIGER WHO CAME TO TEA

A tiger comes to tea. Or, a mother and daughter are at home waiting for father to get home from work. An unexpected visitor arrives. It’s a tiger. Mother invites him inside to drink tea and eat buns, but the tiger eats every morsel of food in the house, and ‘all the water from the tap’. He then leaves. When father arrives home he takes the mother and daughter to a cafe for dinner, since there is nothing to eat at home. The following day, mother and daughter buy more food at the supermarket, and a can of tiger food in case the tiger comes back. It is revealed on the final page that he never does come back.

Man Vs Pink humorously reads a deeper meaning into The Tiger Who Came To Tea:

After a bad day of parenting, who hasn’t wanted to blame the tiger for all the things you haven’t done around the house.

WONDERFULNESS OF THE TIGER WHO CAME TO TEA

The humour in this story comes from its typically ‘picturebook world’ irony: The young reader expects the little girl to be terrified when she opens the front door only to be met with the sight of a ferocious tiger. Instead, the mother and daughter are delighted. They treat him as a guest.

The humour continues as the tiger breaks social norms by eating far more than he is offered. It is funny that he drinks all the water in the tap, since this is a technical impossibility. The irony of non-surprise is repeated when father comes home and finds no food in the house, but instead of being angry about the tiger, decides to turn the event into a special occasion, and treats mother and daughter to a trip to the cafe.

The Tiger Who Comes To Tea is therefore an example of a ‘carnivalesque’ text. A ‘carnivalesque’ text is a kind of book form children in which the child characters interrogate the normal subject positions created for children within socially dominant ideological frames. Carnival in children’s literature:

- is playful

- is non-conforming

- opposes authoritarianism and seriousness

- is often manifested as a parody of prevailing literary forms and genres

- often has idiomatic discourse

- is often rich in language which mocks authority

- often stars a hero who is a bit of a clown or a fool

When a little girl sits down to tea with her mother in 1960s England, she is being trained in ladylike behaviour. I noticed the page one illustration of Sophie shows her sitting with her legs splayed out in ladylike manner. There is nothing sexualised about this as she is wearing tights, but it’s interesting that she sits like an uncultured little girl, but only under the table, where she cannot be corrected by her mother.

Perhaps it’s significant that Judith Kerr herself only came to England at the age of ten. It’s quite possible that she found the culture of drinking tea at a table quite stifling. Let’s imagine there is another text going on in tandem, one in which Sophie sits nicely at the table with her mother, drinking tea without slurping, eating buns without dropping crumbs. In this story, the story about the tiger either happens entirely in her imagination in order to provide some childlike entertainment in a very adult tradition, or the story about the tiger is simply an illustration of how Sophie would like to behave if she were given free rein.

In picture books the climax of the story tends to happen a bit earlier than in other kinds of stories. In this case, the denouement allows the child reader to relax back into normality; we see that order has been fully restored only after all the food in the house has been replaced.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION OF THE TIGER WHO CAME TO TEA

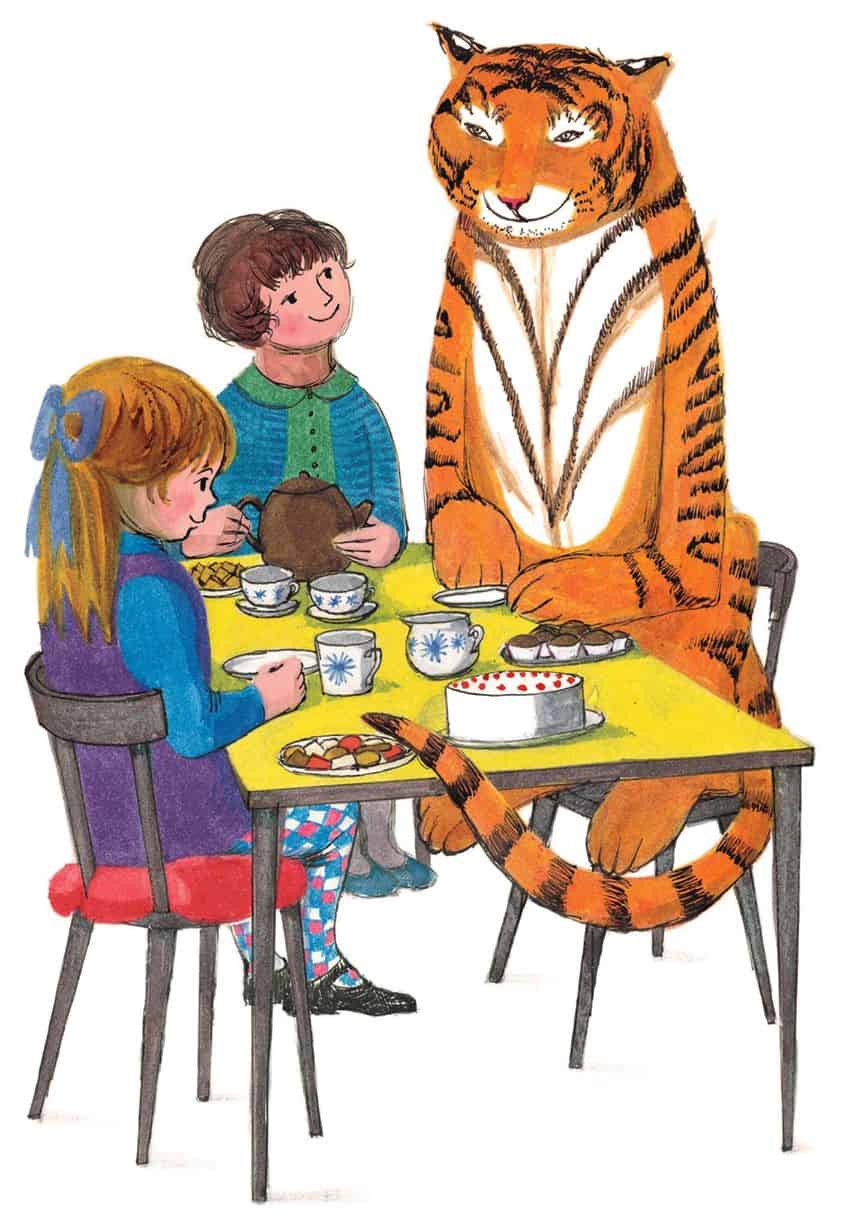

Notice how on the front cover illustration the eyes of the girl are mere dots with a line to suggest the upper eyelid, whereas the eyes of the tiger are quite a bit more detailed and human-like.

(The almond-shaped, comical eyes remind me quite a lot of the eyes on the zebra in the much more modern Z Is For Moose.)

The advantage to drawing child characters in basic form (dots for eyes, single lines for noses) is that the child can then stand in for ‘children in general’ rather than ‘a specific child’, and the child reader is therefore more likely to see themselves in the depiction. The fact that the eyes of the tiger who comes to tea are so human-like add to the humour that derives from his anthropomorphism: Tigers do not come to tea. Nor do tigers look human. The reader’s expectations are constantly foiled throughout this story. First we see a tiger who behaves surprisingly like a human, so we accept him as a human stand-in. He then foils our expectation by behaving badly, eating everything in sight, just as you’d expect of a wild creature.

Is the tiger the mother? Or is the tiger Sophie? I argue that the tiger is both. The cover depicts Sophie with the tiger, whereas page one depicts Sophie with the mother, suggesting the tiger is the mother. But the carnivalesque tradition of picture books suggests that this wild animal is a fantasy that Sophie herself would like to embody: drinking tea from the spout, gobbling as much food as she would like to eat.

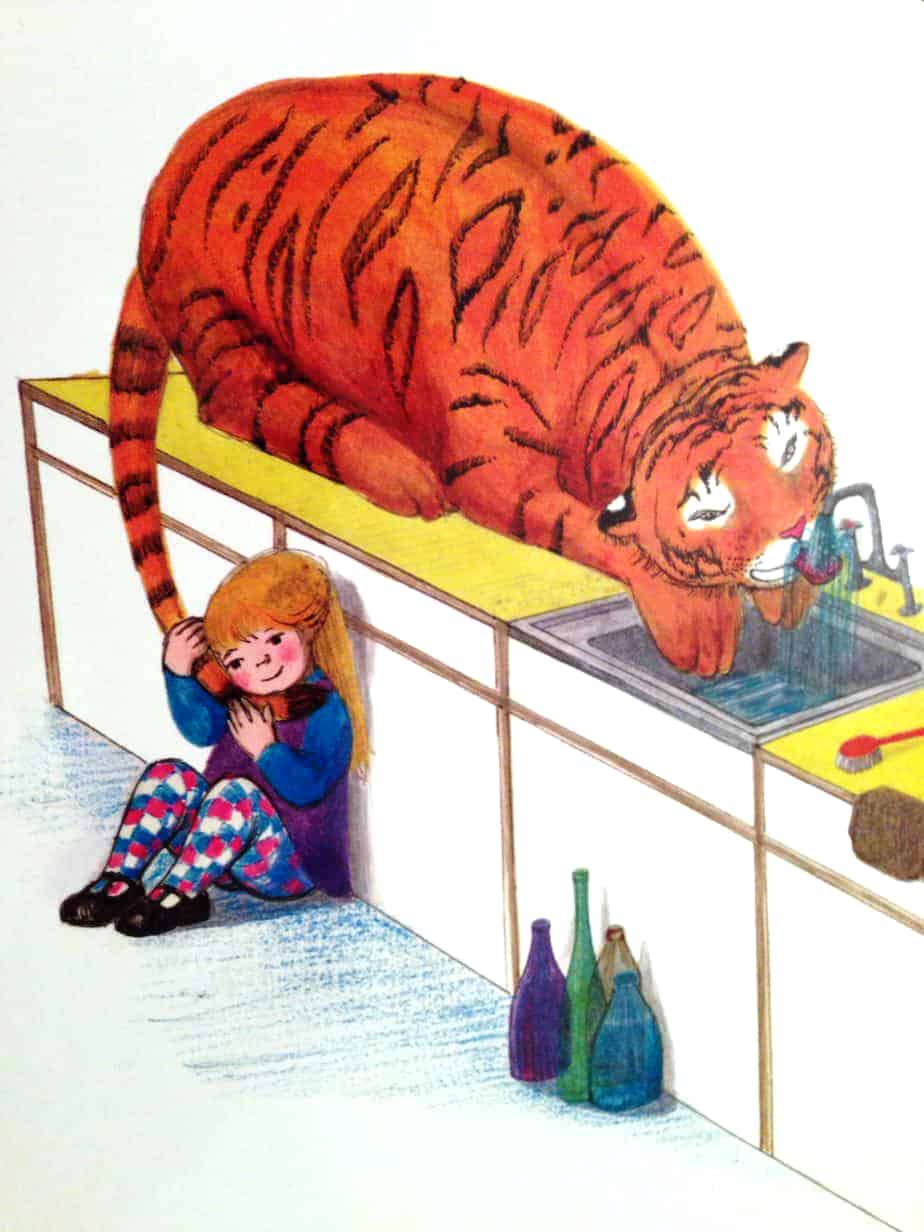

Notice too, that while the tiger is present, she breaks a few tea-time traditions by standing on her chair to offer the tiger some buns, with the chair-cushion pushed onto the floor. Sophie looks adoringly at the tiger as he rummages through the pantry cupboard. Meanwhile, the tiger smiles knowingly at the child reader; the reader knows very well that the tiger is up to mischief, and children are encouraged to revel in his bucking against social norms.

Sophie smiles at the reader on a later page when it’s discovered she can’t have a (dreaded?) bath; the tiger has drunk all the water from the tap. Sophie continues to buck social norms a little when she wears a coat over top of a nightgown with gumboots to a cafe.

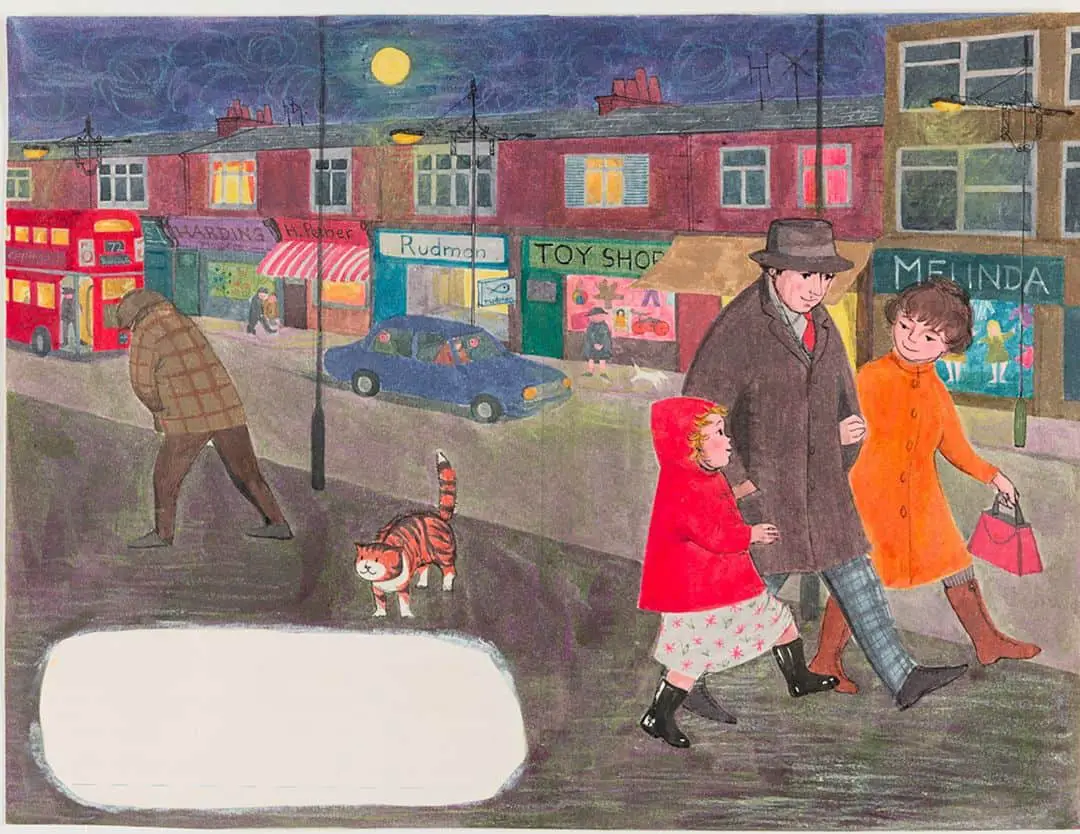

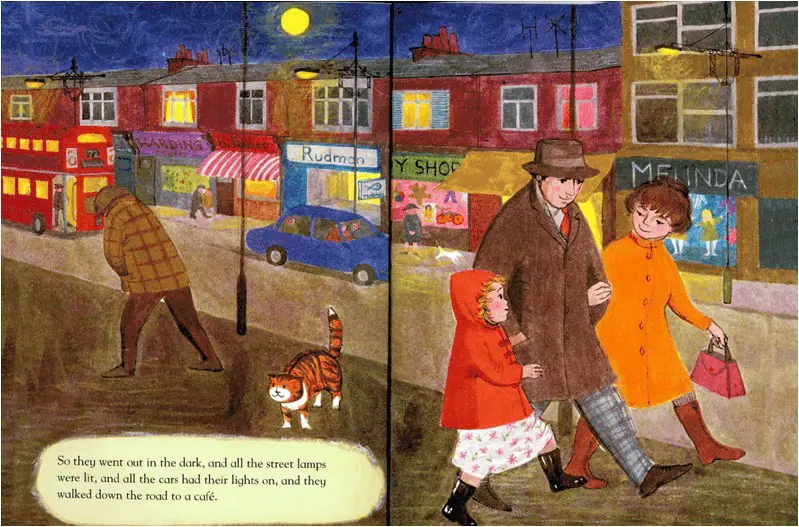

The excitement of being out at night is evoked with a double spread full of colour and a dark blue that contrasts with the white space of the previous pages. Notice also, the cat. This is a cat with stripy, tiger-like markings.

Sophie and her parents have just walked past it. Has Sophie perhaps seen this cat before on her outings, and been inspired by him? The cat has certainly been positioned on the page so that the reader will notice him; he is flanked by the family and a man in a coat heading the other way, hunched over and not noticing anything. The posture of this man seems to say: Are you like this man, or are you noticing, really noticing, the illustrations?

In a more literal reading of the story, this cat (with its knowing smile and off-page gaze) is that this cat is the tiger in disguise, and that he’s off to make mischief at someone else’s house… perhaps yours!

STORY SPECS

Between 28 and 32 pages, depending on the various publishers

First published in 1968, the family dynamics are typical for this era of England: Mother is a housewife who is concerned about preparing Daddy’s dinner. This is a story in which the female members of a family are shut inside. It is the father who leads them into the outside world by ‘taking them’ to a cafe. Notice how the mother is surprisingly small in stature next to the father, perspective aside. The mother as well as Sophie have been involved in this imaginary tale — both can be seen as children for this one afternoon:

This was Judith Kerr’s first book. She followed The Tiger Who Came To Tea with the hugely popular Mog series, about a pet cat rather than a tiger.

The Englishness of this story is apparent from the title. (Tea.) The parents are called ‘mummy’ and ‘daddy’. Regular visitors to the door are the milkman and the grocer boy on his bike. Everyone is still wearing a hat when venturing outside.

Here is an earlier, Picture Lions version of a cover, this time showing the mother as well as Sophie and her tiger:

The Tiger Who Came To Tea has also been adapted into a stage play for children.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST WITH THE TIGER WHO CAME TO TEA

This story reminds me of Gorilla by Anthony Browne. In both of these stories, a child imagines (though the imagining isn’t mentioned) a wild animal who comes to the house because the father is not there as a protective figure. The loneliness of Hannah is far more pronounced than the simple playfulness of Sophie. The Tiger Who Comes To Tea is a warm story, in which everything that happens is good; even the tiger’s mischief is great fun for Sophie to watch.

Another childhood classic in which a cat comes to the door is and makes mischief, of course, the famous Cat In The Hat. The Tiger Who Came To Tea is more similar in tone to that of Dr Seuss than to Gorilla. First published in 1957, it’s likely Judith Kerr was influenced by the Dr Seuss classic.

Then there is Where The Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak, in which Max leaves his bedroom to visit monsters in their own environment. This story is perhaps more similar to Gorilla in that the internal conflict of the child protagonist is resolved by the invention of a wild creature.

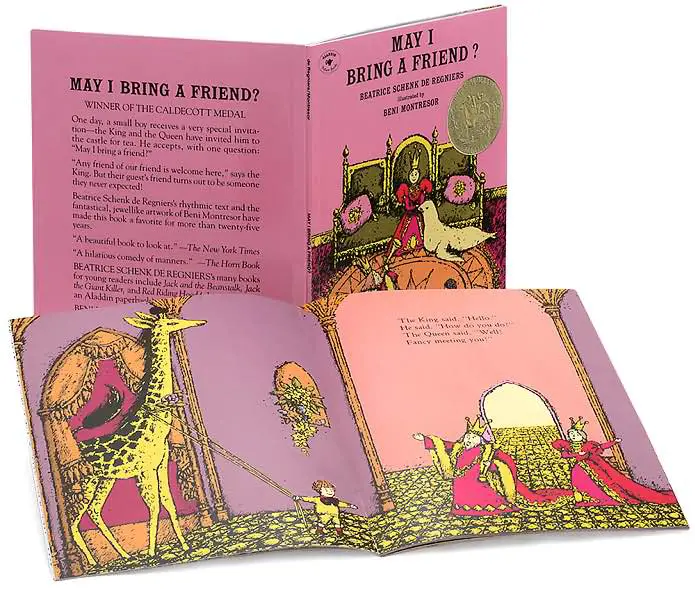

Perhaps the most similar to The Tiger Who Came To Tea, however, is May I Bring A Friend, a carnivalesque tea time adventure from 1964.

WRITE YOUR OWN

If a child encountered a wild animal what would the wild animal naturally do? Now, what’s the inverse of that? How might this wild animal slip up and down the scale of anthropomorphism in order to surprise and delight young readers?

SEE ALSO

The Tiger who Came to Tea: Owp! from We Read It Like This

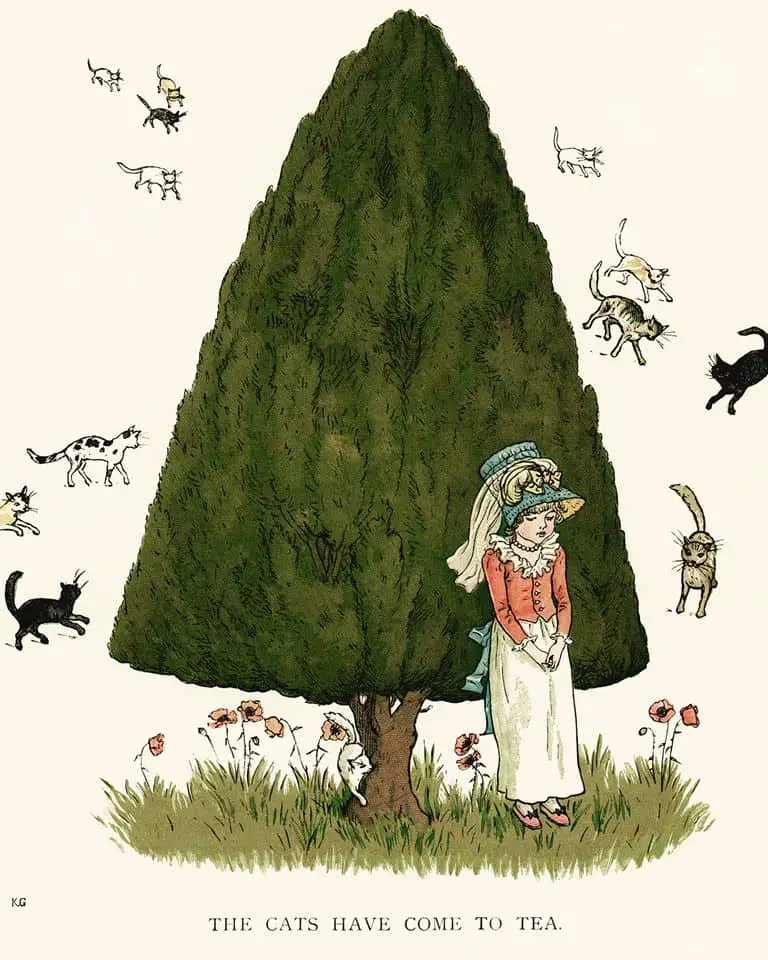

Tigers and other big cats in illustration