Can you guess which country this “eat-me-when-I’m-fatter” produced this fairytale? I’ll drop some clues:

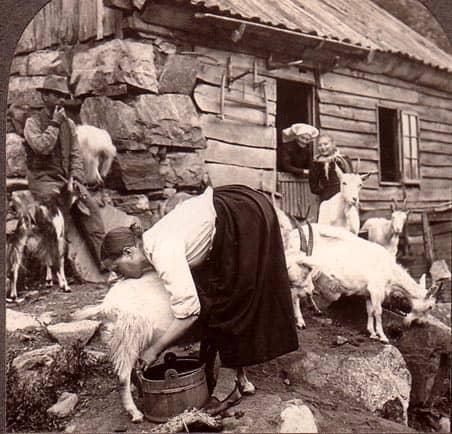

- Goats have historically been very important to this country, for their meat, milk and cheese.

- It’s not a fertile country, which is always better for goats than for cattle and sheep.

- It’s a land of mountains.

Yes, it’s Norway.

- From ca. 1700 until 1850 the human population as well as the number of goats and sheep of this country almost tripled.

- The increased pressure on the natural resources worsened the living conditions for people and animals alike.

- A characteristic feature of this period was the herding of single flocks by children. During the daylight hours, this was a precaution against predators as well as a way of keeping the animals off the areas meant for the harvesting of winter fodder. At night, the small flocks were in some places gathered in mobile corrals guarded by adults with dogs.

- The Three Billy Goats Gruff was first published between 1841 and 1844, when goats were important to survival. The idea of a creature taking the life of a goat was not so far removed from taking the life of a child (due to the resultant starvation).

Rudin has a good sense of rhythm, and has retained all the things that are fun about this story as a read-aloud, but I feel the point of it is lost.

WHERE TO HEAR THIS STORY

I also recommend the reading by Parcast’s Tales podcast. “The Three Billy Goats Gruff” is episode 89, 23 September 2020. This is not a straight reading but a retelling using more contemporary (and engaging) language, with music and Foley effects. I really enjoy listening to classic tales at the Parcast Tales podcast.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE THREE BILLY GOATS GRUFF

PARATEXT

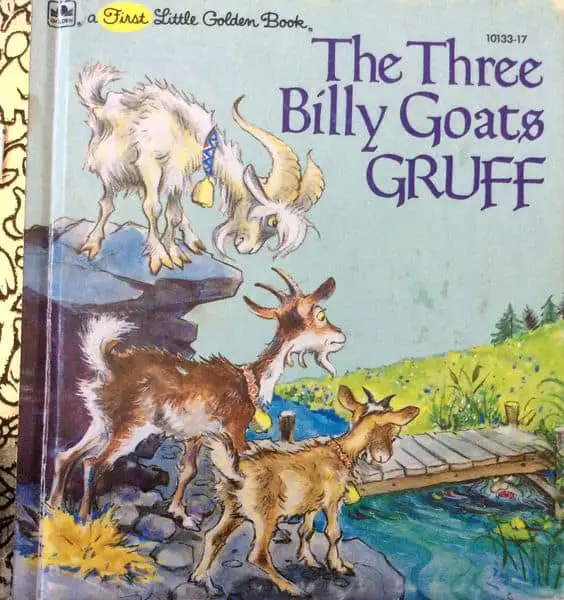

My childhood version of The Three Billy Goats Gruff was unfortunately — I see now — not a good one. It’s the small format Little Golden Book published in 1982, retold by Ellen Rudin. (The 1980s were chocka block full of retold fairytales.)

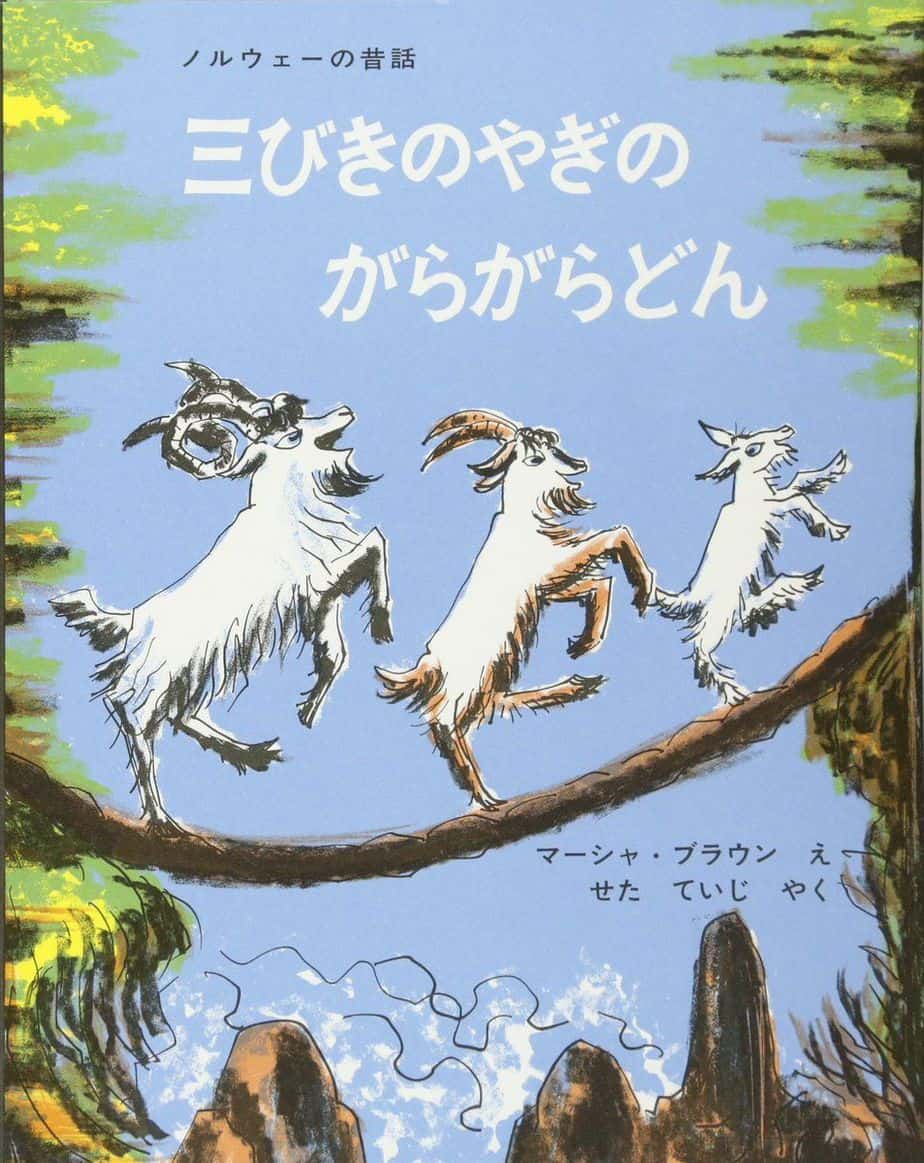

The Japanese title is ‘Sanbiki no yagi no garagaradon’, in which the ‘gara gara don!’ is onomatopoeic. The Japanese language is beautifully onomatopoeic and mimetic, a fact often reflected in tranlations of children’s stories.

SHORTCOMING

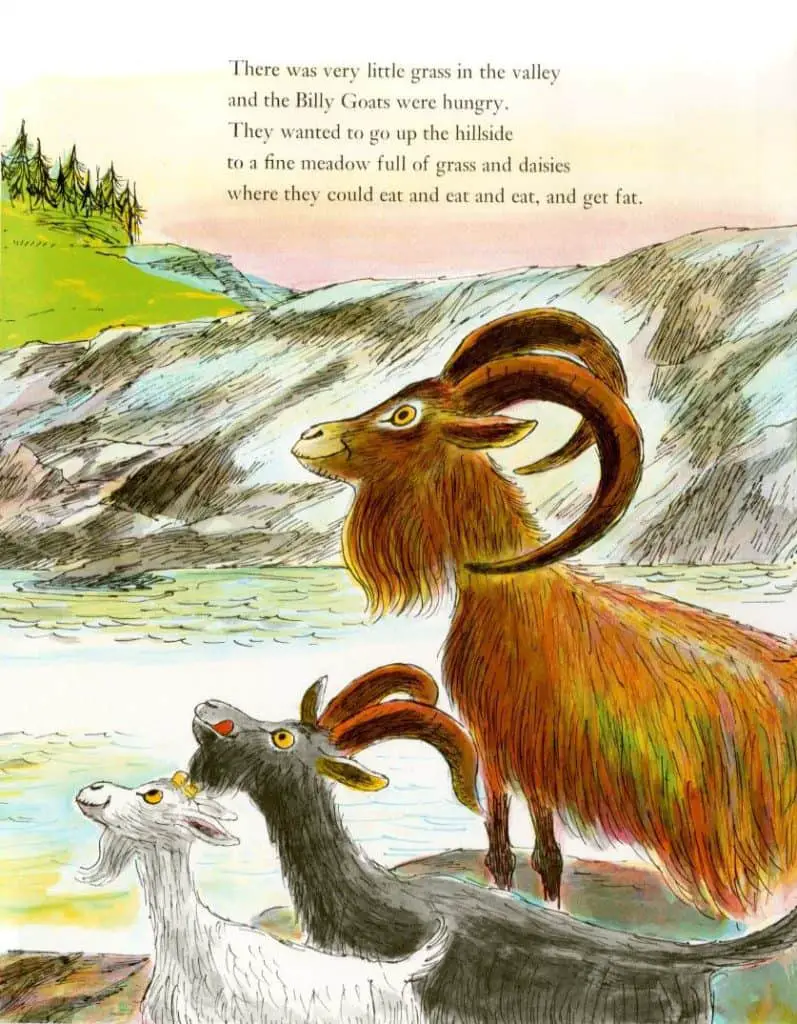

This is not clear from the text of the Little Golden Book version, but the goats need to get to the other side of the bridge because there is nothing to eat on their current side. Perhaps if I’d looked at the pictures more carefully as a child I’d have noticed all the rocks on the left, contrasting with the healthy green growth on the right. But I just assumed the goats happened to be standing on a pile of rocks and that the greenish hue of the background was perfectly good grass.

The stakes were much higher than that.

Here is a page from a completely different version, illustrated by Paul Galdeone. “There was very little grass in the valley” offers a clear need in the text (as well as in the illustration.)

Notice these goats looking left. In the vast majority of Western picture books the main characters look right, encouraging the reader to look forward to what’s overleaf.

DESIRE

The three billy goats gruff have to cross the bridge. They’re not doing it for the adrenaline rush.

They desire food.

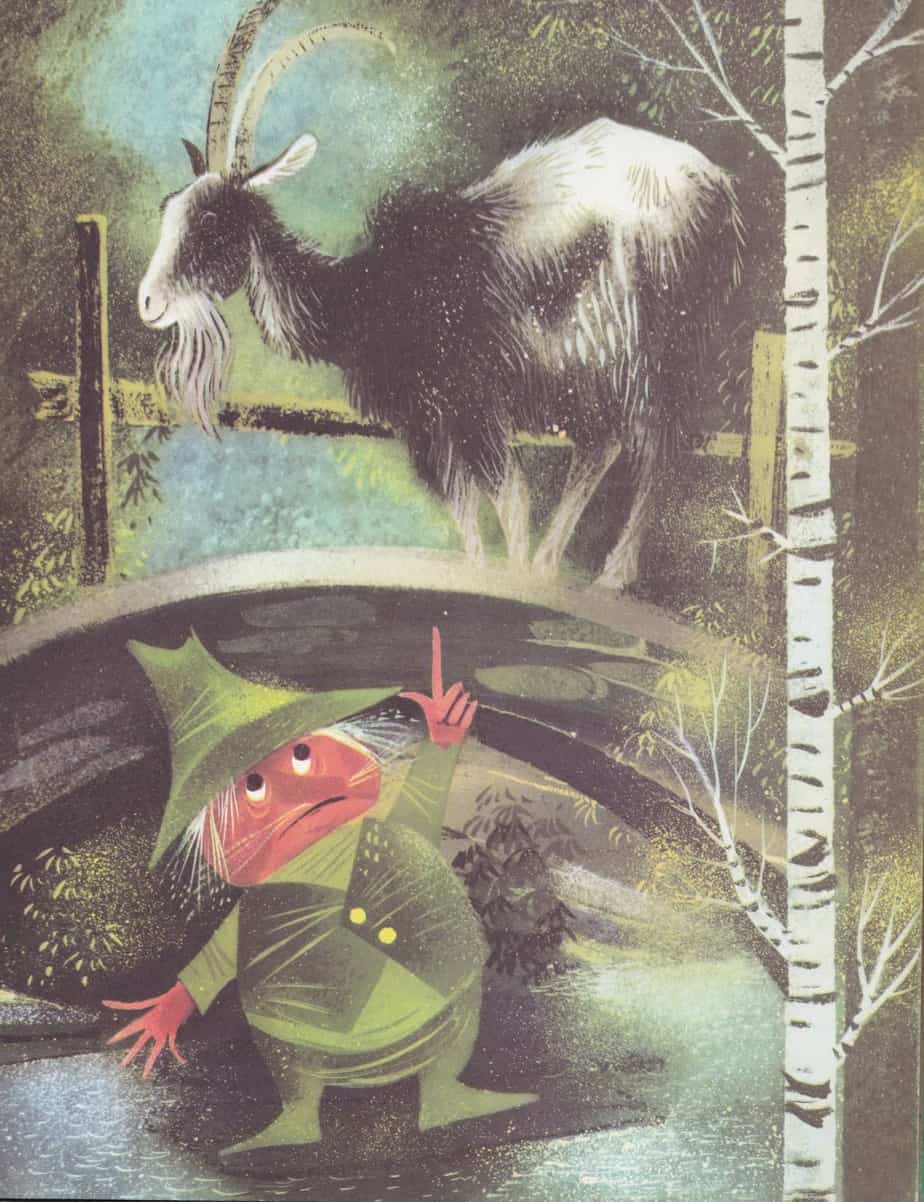

OPPONENT

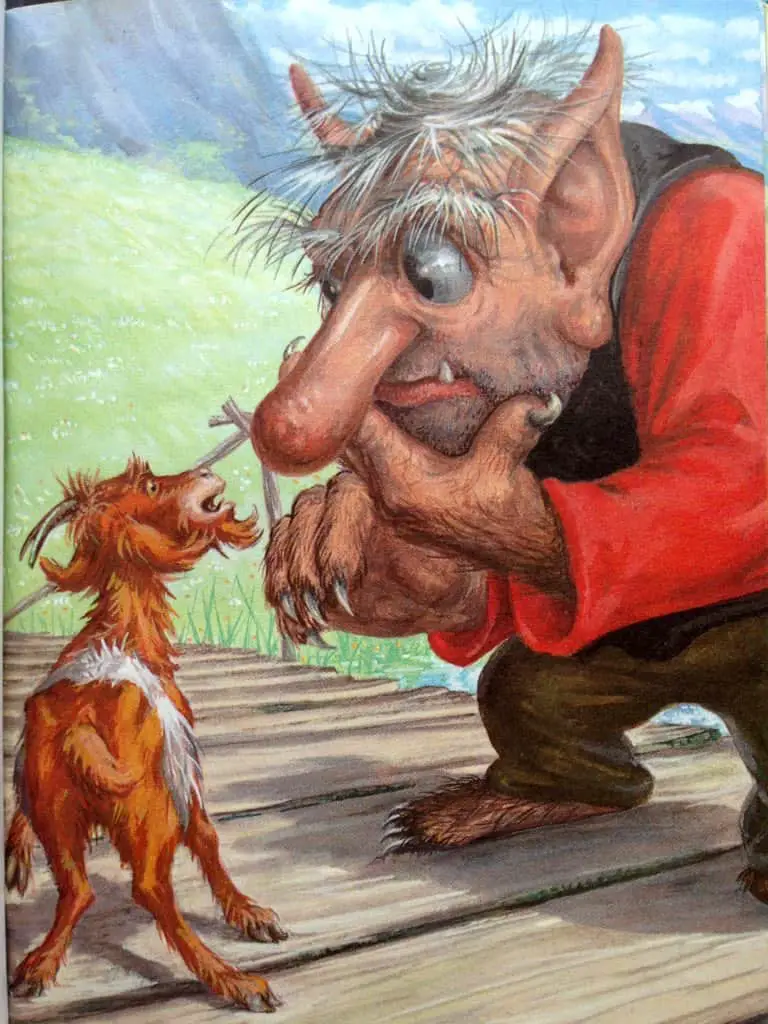

The troll under the bridge.

Trolls featured prominently in Norwegian myth and legend. They were originally believed to be actual supernatural beings who lived in isolated rocks, mountains, or caves. They lived together in small family units, and were rarely helpful to human beings. Later they became more concretized. They became more evil and although they were often ugly, it was also thought that trolls would walk among us, undetected. Like vampires, they have trouble with sunlight. I suppose this is why the troll in this fairytale lives under a bridge.

Roald Dahl was influenced by such mythology. You’ll find aspects of trolls in some of his stories (along with witches, of course). The Trunchbull of Matilda feels a bit troll-like in her one-sided badness and ugliness. So do The Twits.

PLAN

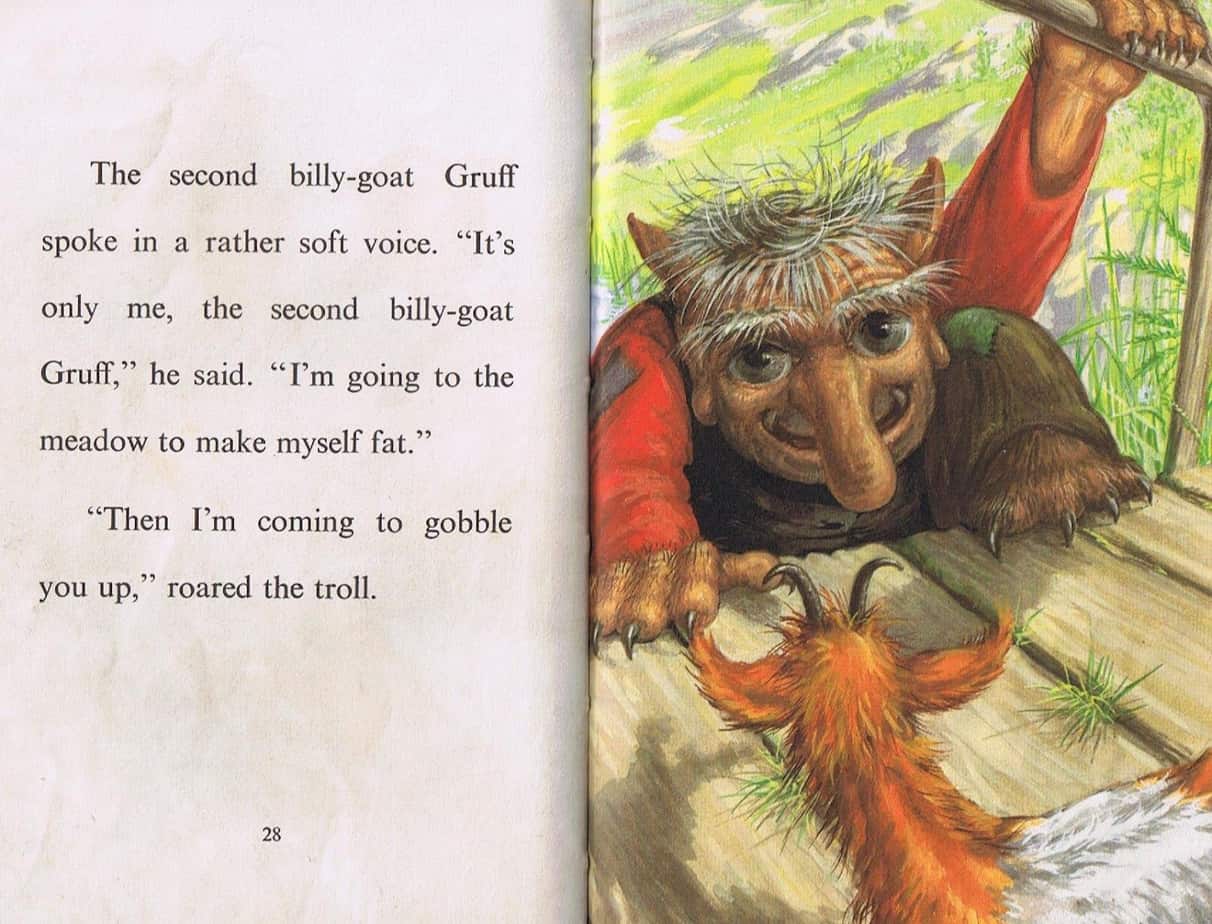

One day the littlest Billy Goat Gruff said, “I cannot wait any longer. I am going t cross the bridge and eat the sweet, green grass.”

“We will come, too,” said his brothers. “We will be right behind you.”

This is the most problematic part of the retelling, because it always seemed to me that each goat genuinely attempted to sacrifice the older one in order to save himself. I feel the ‘plan’ should be made clearer here. These brothers are working together strategically rather than looking after self-interests.

BIG STRUGGLE

“Then I am coming up to eat you!” the troll shouted. And he climbed onto the bridge.

Big Billy Goat Gruff was not afraid.

“I would like to see you try!” he said.

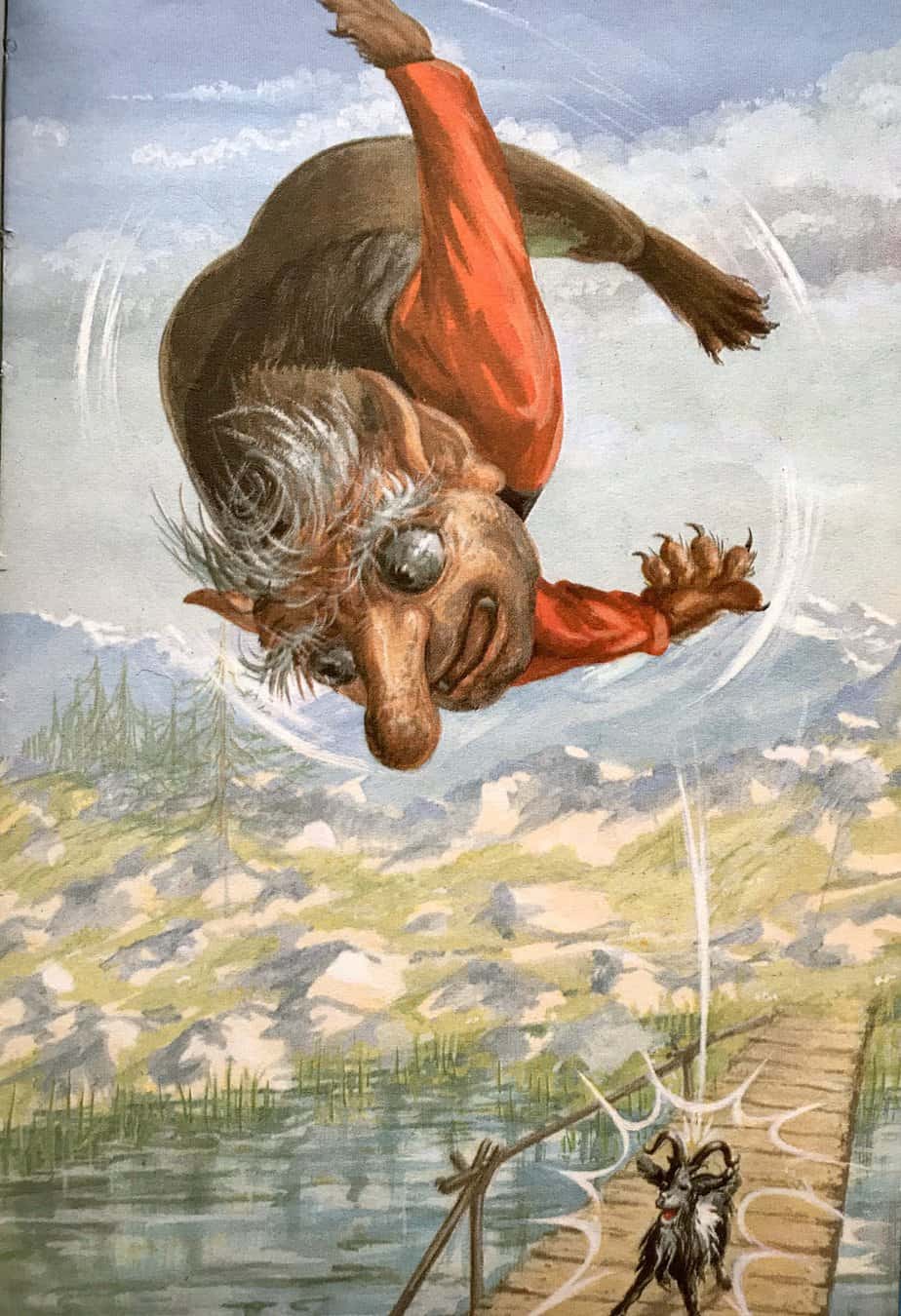

He rushed at the troll and butted him with his horns. The troll fell off the bridge and disappeared, leaving no trace.

Since trolls can’t be exposed to light, the simple act of coaxing the troll out from under the shade of the bridge may have been all that was needed!

ANAGNORISIS

For me this story failed, because I had no revelation. I was supposed to realise at the end that these goats had worked together. Instead I wondered why the older goats didn’t spend the rest of their lives holding grudges against the younger ones.

I was supposed to learn that working together can defeat evil.

NEW SITUATION

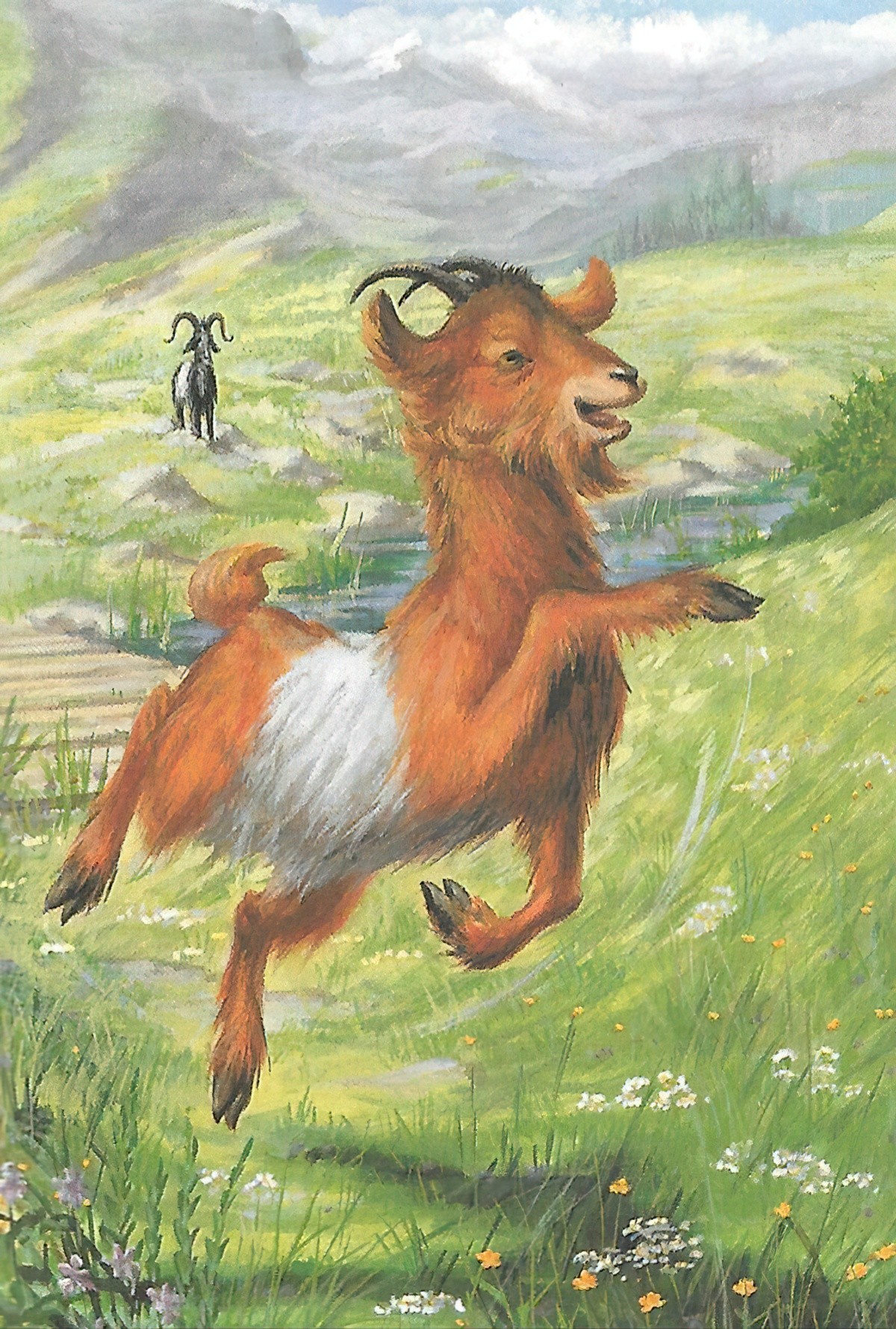

After that the three Billy Goats Gruff crossed the bridge whenever they liked and ate their fill of sweet, green grass.

And the horrible, mean troll never bothered them again.

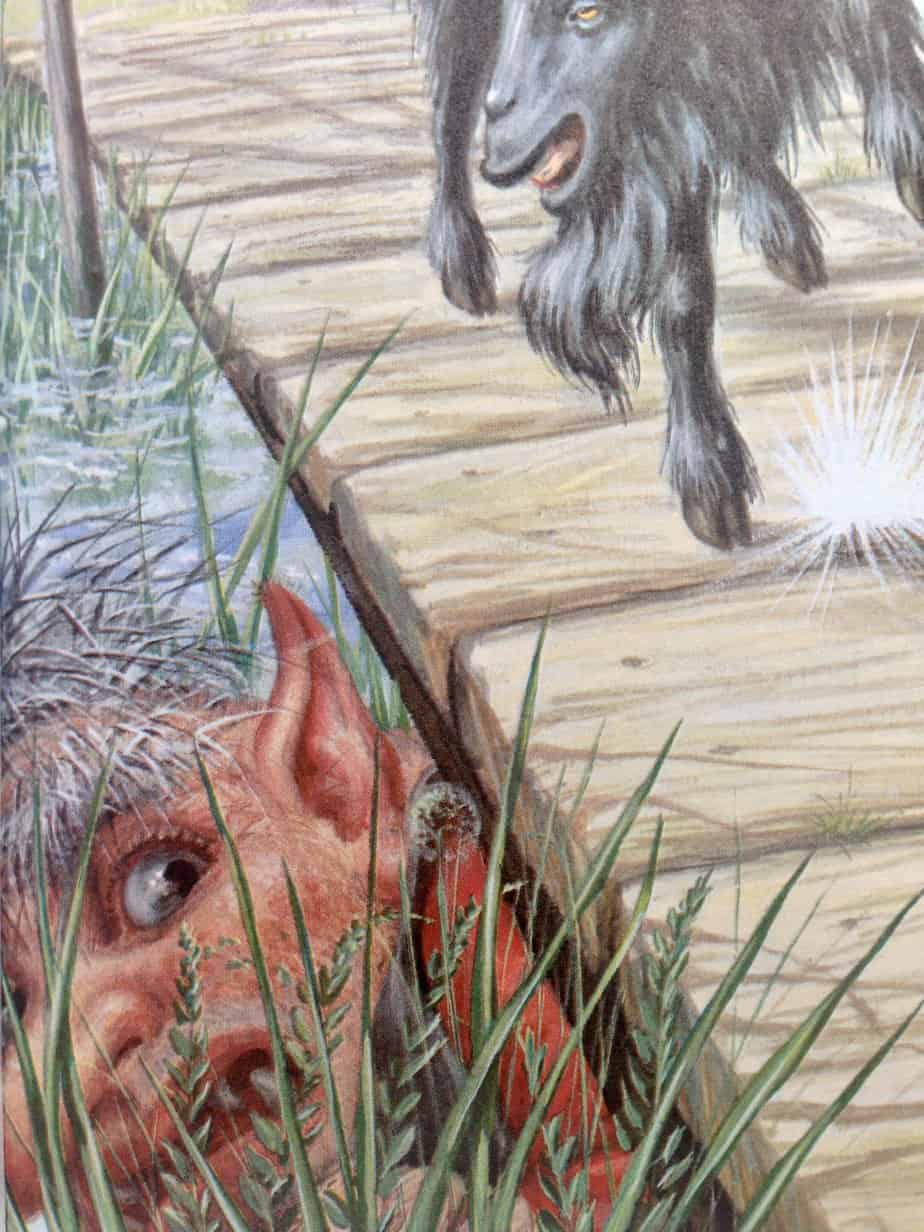

from a Ladybird edition of The Three Billy Goats Gruff, illustrated by Robert Lumley

Related

My revisioning of this tale is called Trip Trap. You can read it here.

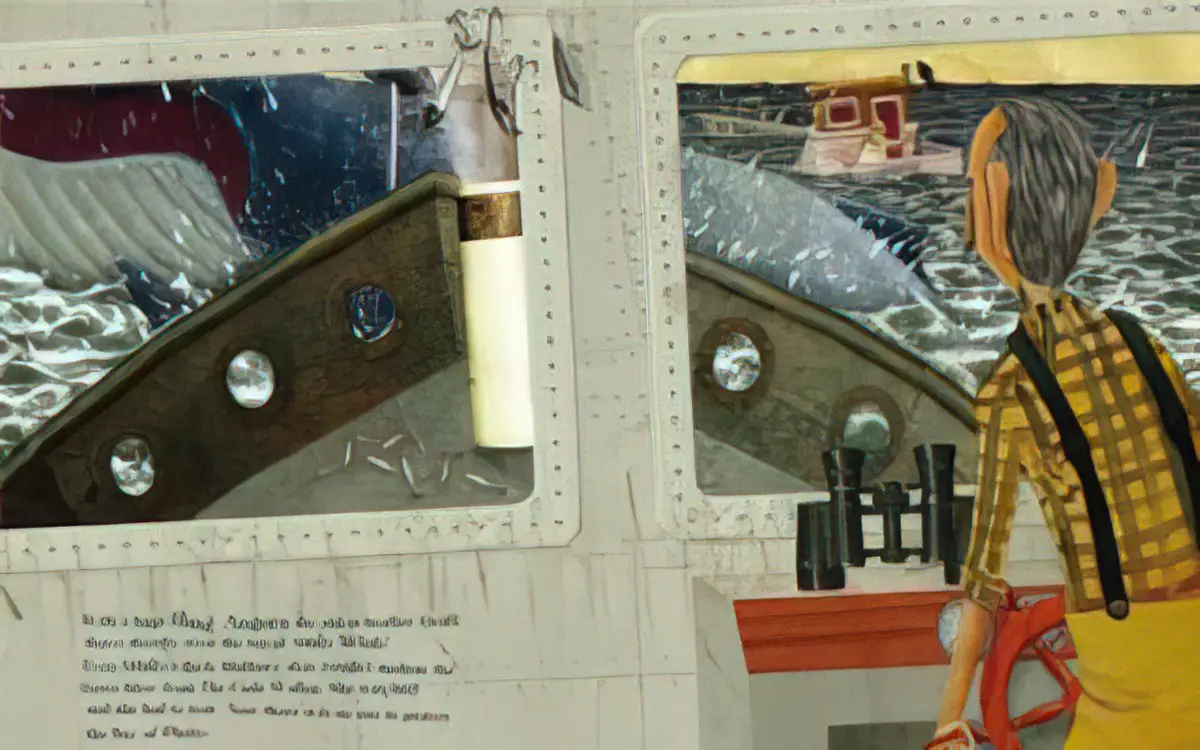

THE THREE FISHING BROTHERS GRUFF BY BEN GALBRAITH

Ben Galbraith is a Kiwi illustrator who says on his blog that he’s ‘quite colour blind’, which kind of backs up my theory that colour selection is far more scientific than successful artists like to make us think, and that it can be learned. (There are also tools to help artists out like Adobe Kuler and that picker thing you get in Illustrator etc.)

The art in this book is an appealing mixture of textures and collage. Sometimes this art style can look too digital, but it’s done well here. I like the humour of a boat called ‘the cod’s wallop’. If I had a boat I might call it that. The author is a keen fisherman, and this comes through in the story. The New Zealand way of speaking and its sea setting also comes through quite strong, and the issues about over-fishing aren’t specific to New Zealand, but remind me of the problems I see on any episode of Coast Watch. It was an inspired choice to set the story in ‘Bay of Plenty‘ and in ‘Poverty Bay‘, which are not only allegorical names but are actually real places.

Header painting by Hans Fredrik Gude (1825 – 1903) depicts the Norwegian Mountains, 1856, a landscape unlike the lushly grassed hills in children’s picture books.

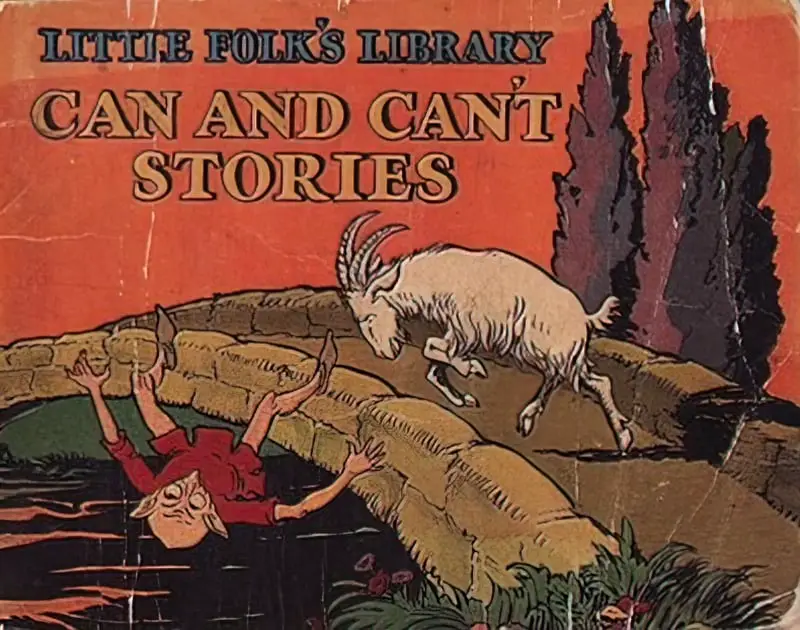

Can and Can’t Stories Newson & Company in 1928