The entire story of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter (1901)is free to read at Project Gutenberg. But bear in mind that Beatrix Potter was fussy about the size of her book and everything about the printing process. This story is therefore meant to be read as a bound copy, in its original small size, rather than as part of an anthologised collection, or online.

For more on that: The Size And Format Of Picturebooks. The size of a children’s book contributes to the experience of reading.

PROBLEMS WITH PETER RABBIT

As Marjery Hourihan points out in Deconstructing the Hero, Peter Rabbit is basically an Odyssean story. A male hero goes out, has an adventure, faces death and then arrives home, changed. Beatrix Potter was following a long tradition of storytelling when she wrote this one.

PETER RABBIT AND GENDER

It’s worth looking closely, too, at the gender attitudes reflected in this tale. This old story evinces attitudes you might expect to have evolved since this story was written, but which haven’t really, in popular children’s literature. Although Peter Rabbit’s sisters are all wearing pink shawls, it’s coincidental that it was only several decades later that the colour pink started to be associated with femininity, and blue with masculinity. (Perhaps this partly explains the enduring popularity of Peter Rabbit merchandise given as modern baby gifts.) For links on the Pinkification of Everything, see here.

WONDERFULNESS OF PETER RABBIT

Influences

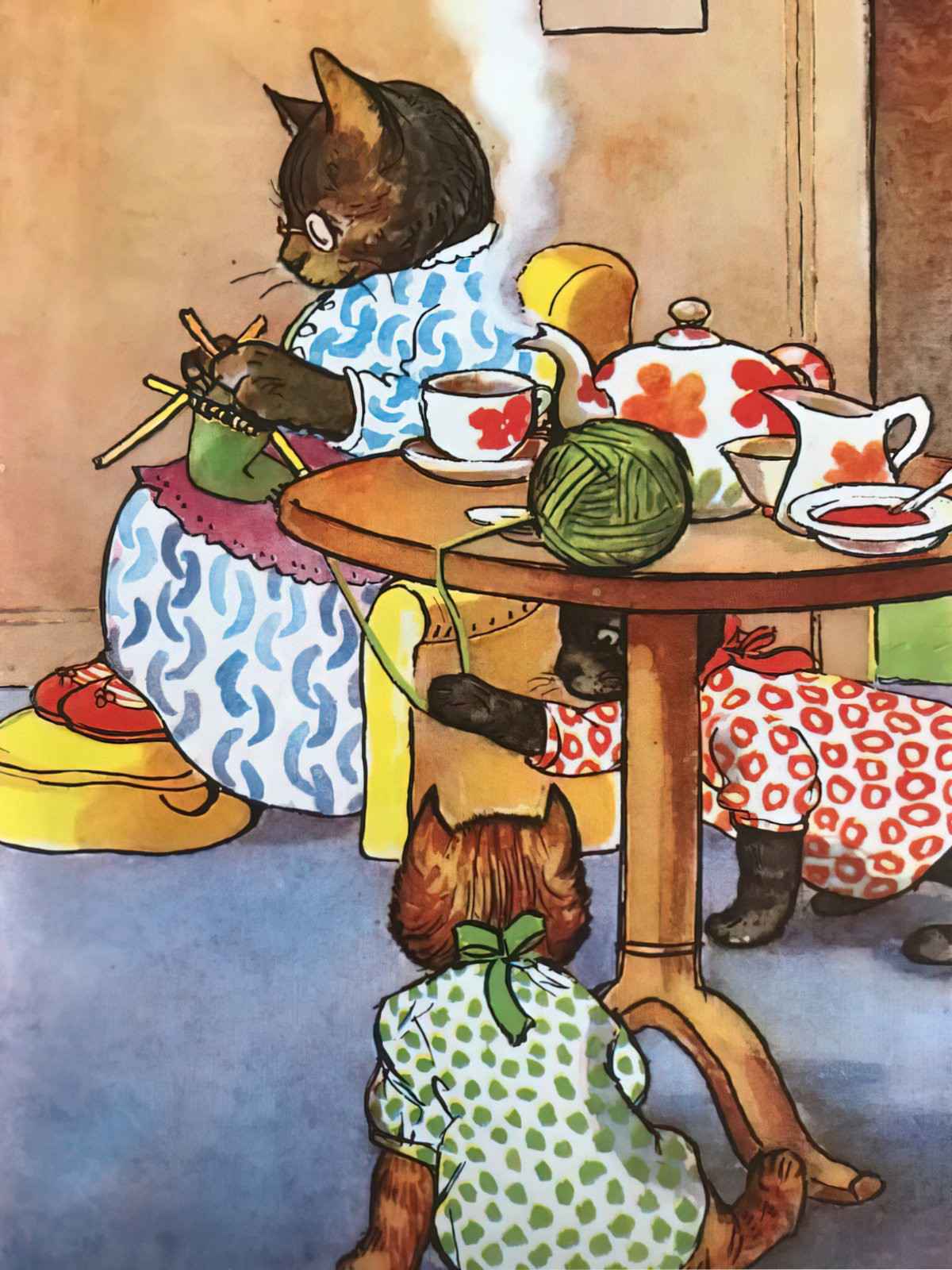

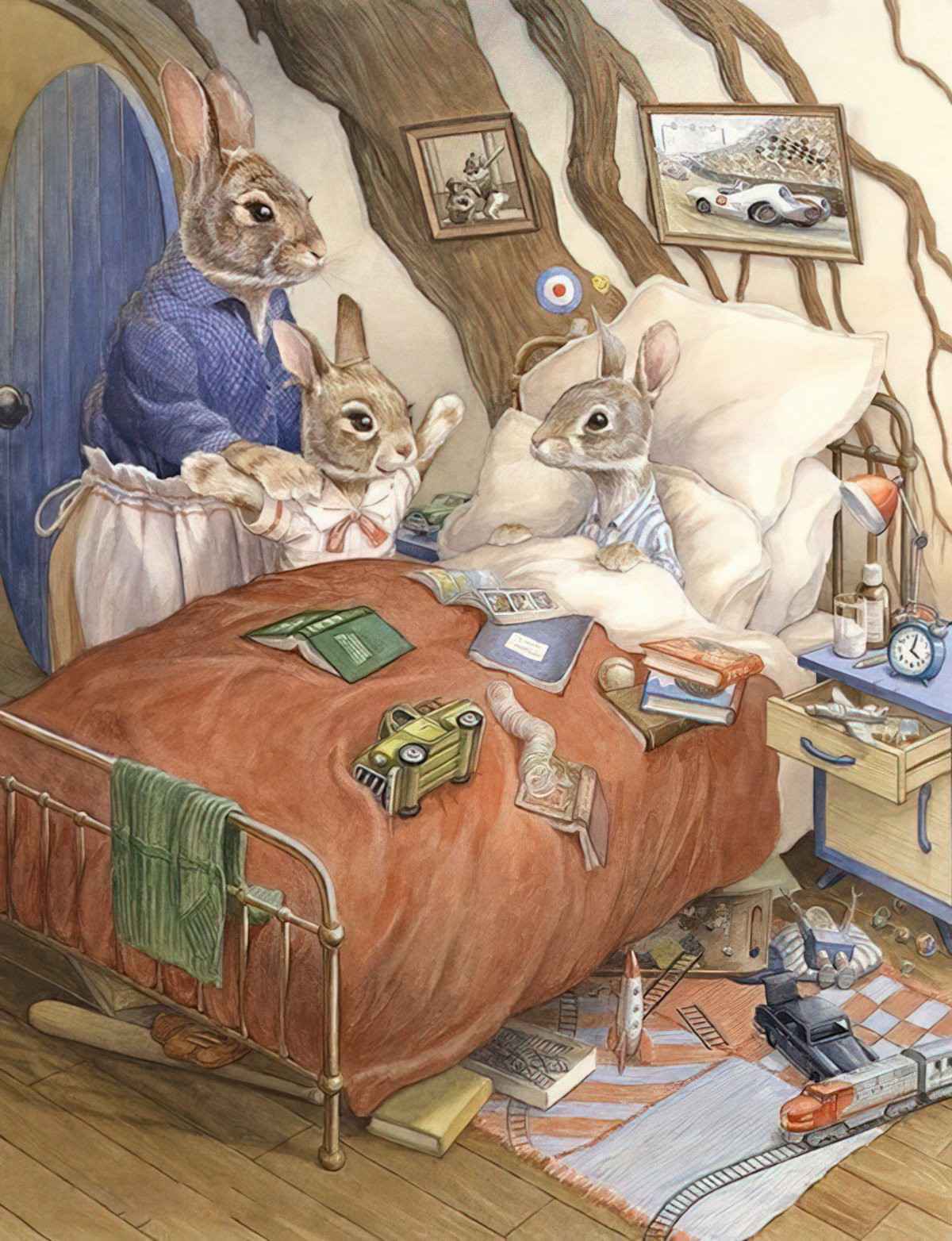

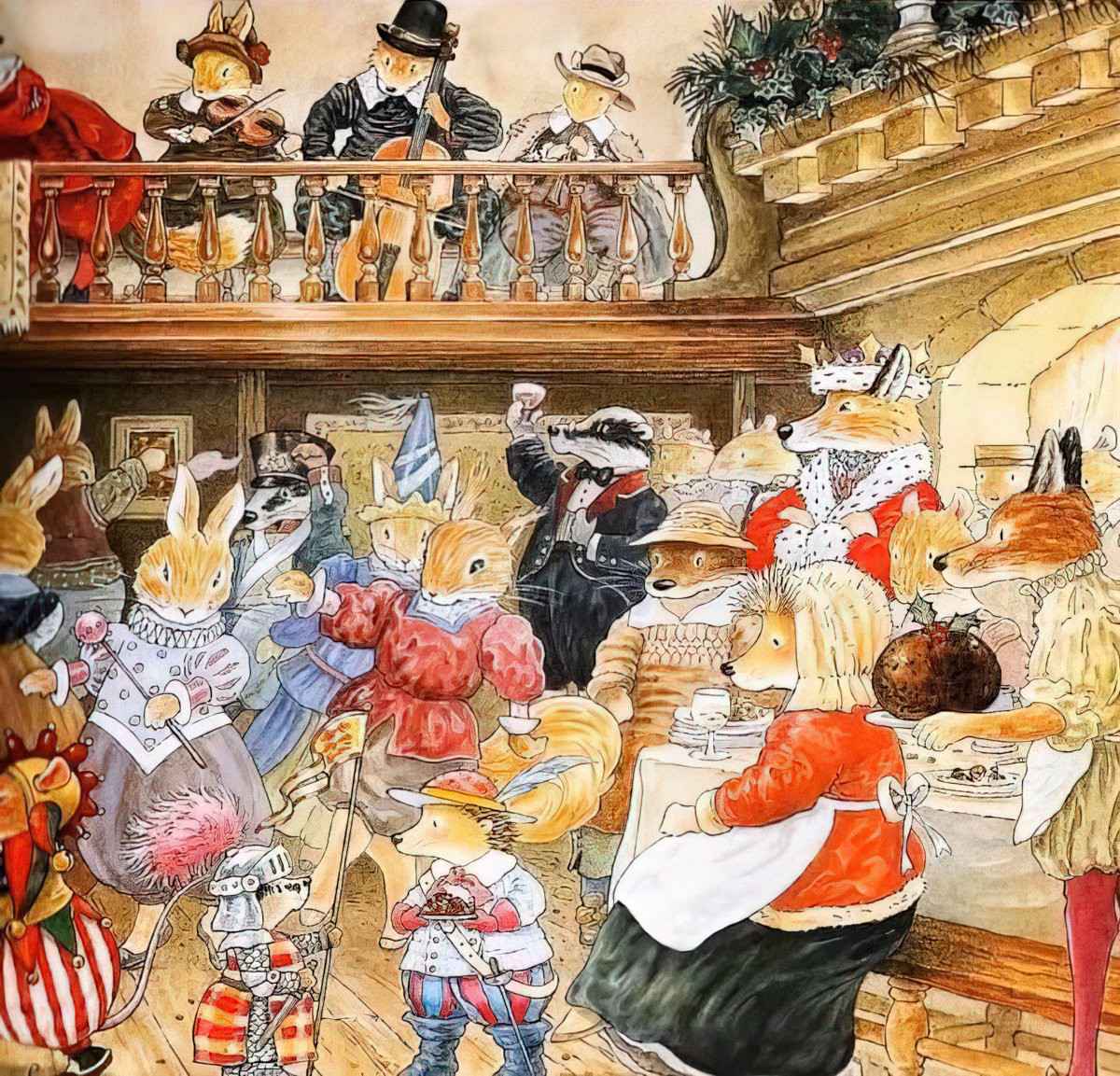

Now that animals in picture books are super common, it’s easy to forget that Beatrix Potter popularised a new kind of story. Potter is hugely influential in children’s book world, specifically for her animals dressed as humans.

DOROTHY KILNER

But Potter herself was in turn influenced by all who came before. She almost certainly would have read Dorothy Kilner’s Life and Perambulations of a Mouse, published 1783. This story was influential in children’s book world because it was the first animal story told from the point of view of the animal, without also delivering a sermon to its young readers.

UNCLE REMUS FABLES

In her book Animal Land, Margaret Blount is confident that Beatrix Potter was also influenced by Uncle Remus fables.

Uncle Remus fables are African stories. They were rewritten with an American setting and published in 1881. Blount describes the main difference between Potter’s magical world and that of the Uncle Remus stories in this way:

One had the feeling that if one had been lucky enough to live in America in this golden age, these witty talking animals [from the Uncle Remus fables] would have been in one’s backyard or farm or briar patch; whereas Beatrix Potter’s animals with their human clothes and lakeland landscapes belonged to a naturalists’ fairy tale ‘now’ that wasn’t and could never be. They might exist, but one could never meet them. As soon as they were clearly observed their clothes would vanish, they would drop on to all fours and run away, like Mrs Tiggy Winkle.

THE ORIGINALITY OF BEATRIX POTTER

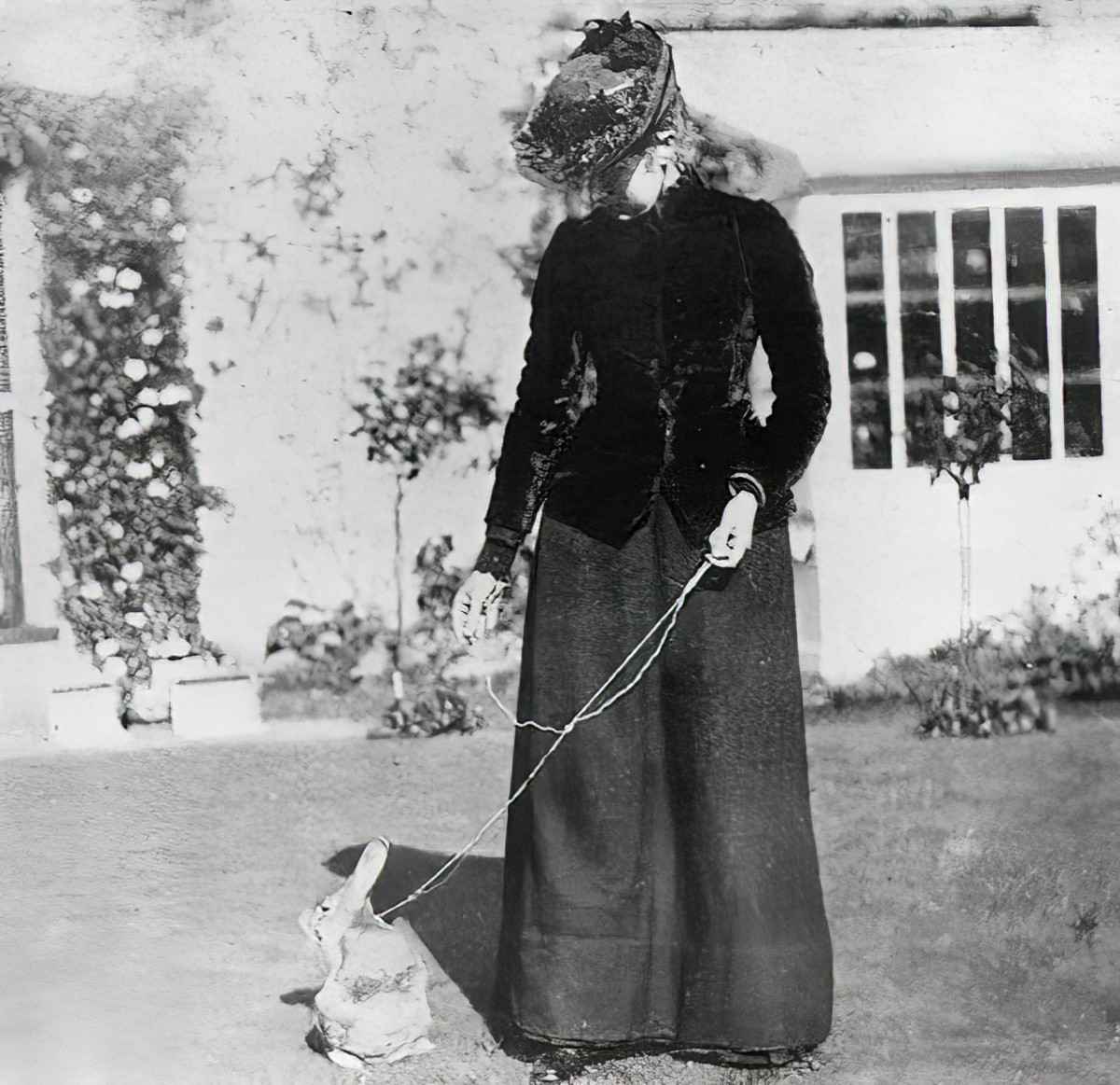

Despite the influences, Potter added a lot to the animal story genre of children’s books, not least because of her illustrations. In a biography of Beatrix Potter, Linda Lear writes that Potter

“had in fact created a new form of animal fable in: one in which anthropomorphic animals behave as real animals with true animal instincts”

Rather than cartoons, Potter’s animals looked like actual animals. That’s because Potter drew from life where she could. (Where she couldn’t, she didn’t do a great job; see her chipmunks.) Potter also understood how her animals behaved. Peter Rabbit’s nature is familiar to people who know about rabbits…

…and endorsed by those who are not … because [Potter’s] portrayal speaks to some universal understanding of rabbity behaviour.”

Lear, Linda (2007), Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature, New York: St. Martin’s Press

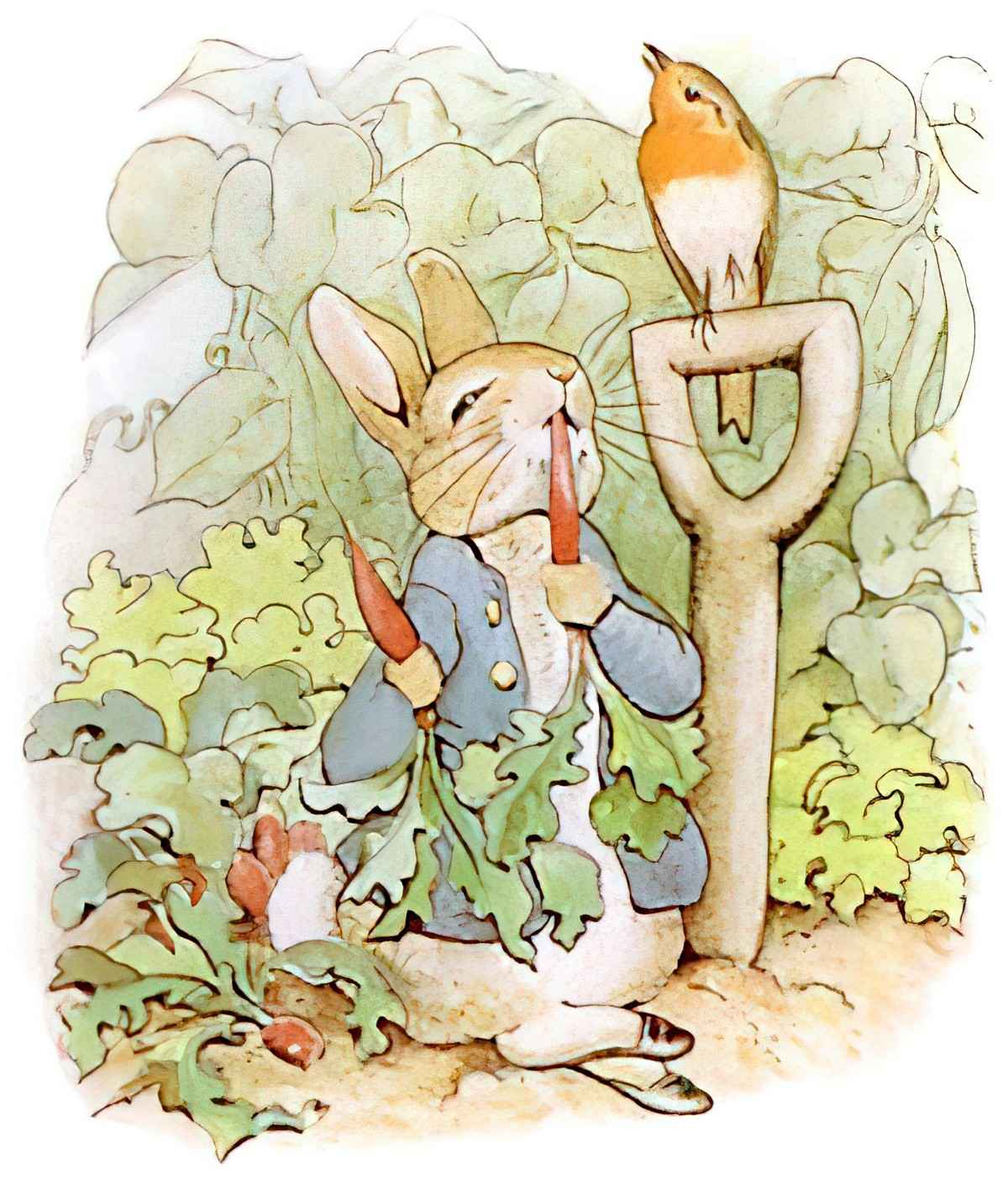

The Significance Of Clothing

In many of her books, but particularly in Peter Rabbit, Beatrix Potter makes a consideration of clothing her central thematic concern. Although the story seems to be a moral allegory about why human children should obey their parents, it is Peter’s human clothing that hampers his attempts to escape after he acts like a rabbit and steals vegetables from a garden, and the book as a whole subtly explores the question of whether Peter should act on instinct, as an animal, or do as his mother wishes and act like a civilised human. The dilemma is not resolved, even despite the apparent message about obedience implied by the conclusion, in which the sisters who acted like good humans get food that Peter is too sick to eat; for Peter is rabbit enough that he seems unable to resist the rabbit-like actions that get into trouble, and we are told he has already lost his human clothing earlier in the same fortnight. The pictures add to the ambiguity: Peter looks and acts brave in his human clothing at the point when he is acting on natural rabbit instincts and stealing vegetables, but when he loses his clothes and feels a human desire for the safety and civilised comforts of home, the pictures of him express the timidity of a natural rabbit.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures

The Japanese movie length anime Wolf Children (based on a comic) features the exact same moral dilemma. The ‘wolf children’ must decide if they would prefer to live their adult lives in restricted civilisation or as part of the dangerous wild.

Instinct Vs Nature

The story of Peter Rabbit sums up a central dilemma of childhood—whether one should act naturally in accordance with one’s basic animal instincts or whether one should do as one’s parents wish and learn to act in obedience to their more civilised codes of behaviour. The importance of that dilemma may explain why picture books about creatures who look and sometimes act like animals but who talk and sometimes act like humans continue to be so prominent: these curiously ambiguous creatures actually represent our understanding of childhood better than any less ambiguous creature might. It is not surprising that the animals most frequently depicted in picture books are rabbits, mice, and pigs; rabbits and mice are small enough to express the traumas of small children in a world of large adults, and pigs have a sometimes disturbingly childlike pink chubbiness.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures

Margaret Blount considers Peter Rabbit’s clothing very much a part of him:

In the work of Leslie Brooke, animals’ clothes are assumed for amusement only — perhaps the Bear thought that his black coat and striped trousers were correct wear for his Sentimental Air. But Peter Rabbit’s blue jacket with the brass buttons is a natural part of him, a serious matter when lost, as a child’s would be — all the more serious because it was quite new.

Animal Land

The same applies to Jeremy Fisher:

For many half-animal, half-human characters, clothing is of great significance. It marks them off from the purely animal, from the completely savage creatures who don’t wear clothing, but it’s often a source of discomfort, something that prevents them from behaving like their natural selves. Both Peter Rabbit and Jeremy Fisher almost die because they act like humans. Peter’s shoes and jacket buttons nearly lead to his death, and Jeremy dressed and acting like a human fisherman forgets his frog instincts about avoiding trout. But then both Peter and Jeremy escape disaster because they act like humans, Peter by remembering human words about the dangers of cats spoken by his cousin Benjamin, and Jeremy because his mackintosh tastes so unfroglike.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature by Nodelman and Reimer

Specificity of Detail

Beatrix Potter was specific in her writing, a trait she shared alongside E.B. White. (Comparing E.B. White’s drafts of Charlotte’s Web with the final product, it’s clear how he edited his final draft for as much specificity as possible.) ‘Cold weather settled on the world’ became ‘After Christmas the thermometer dropped to ten below zero.’

Examples of specificity from Peter Rabbit:

Mrs Rabbit went to the barker’s and ‘bought a loaf of brown bread and five currant buns’. When Peter invades Mr McGregor’s garden, ‘First he ate some lettuces and some French beans; and then he hate some radishes’.

For more on writing detail, see here.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

Placement Of The Main Character On The Page

Peter Rabbit is at the centre of almost every one of Beatrix Potter’s pictures of him; the focus is less on what Peter encounters than on how he reacts to it. But he moves out of the centre when he sees a cat and each time he sees Mr. McGregor; as the text refers to what he sees rather than to what he feels, we see it with him.

Nodelman

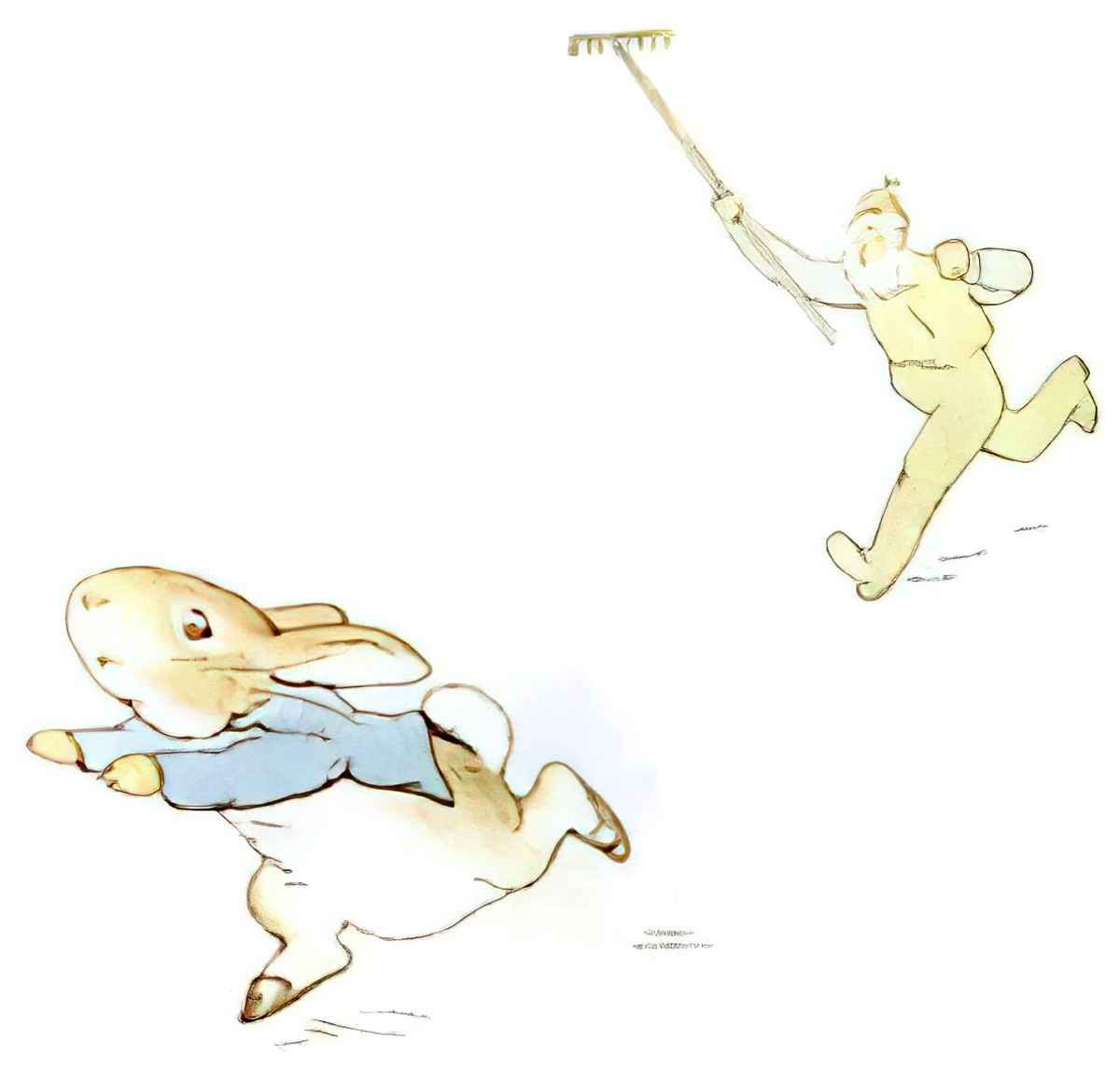

Depiction Of Movement

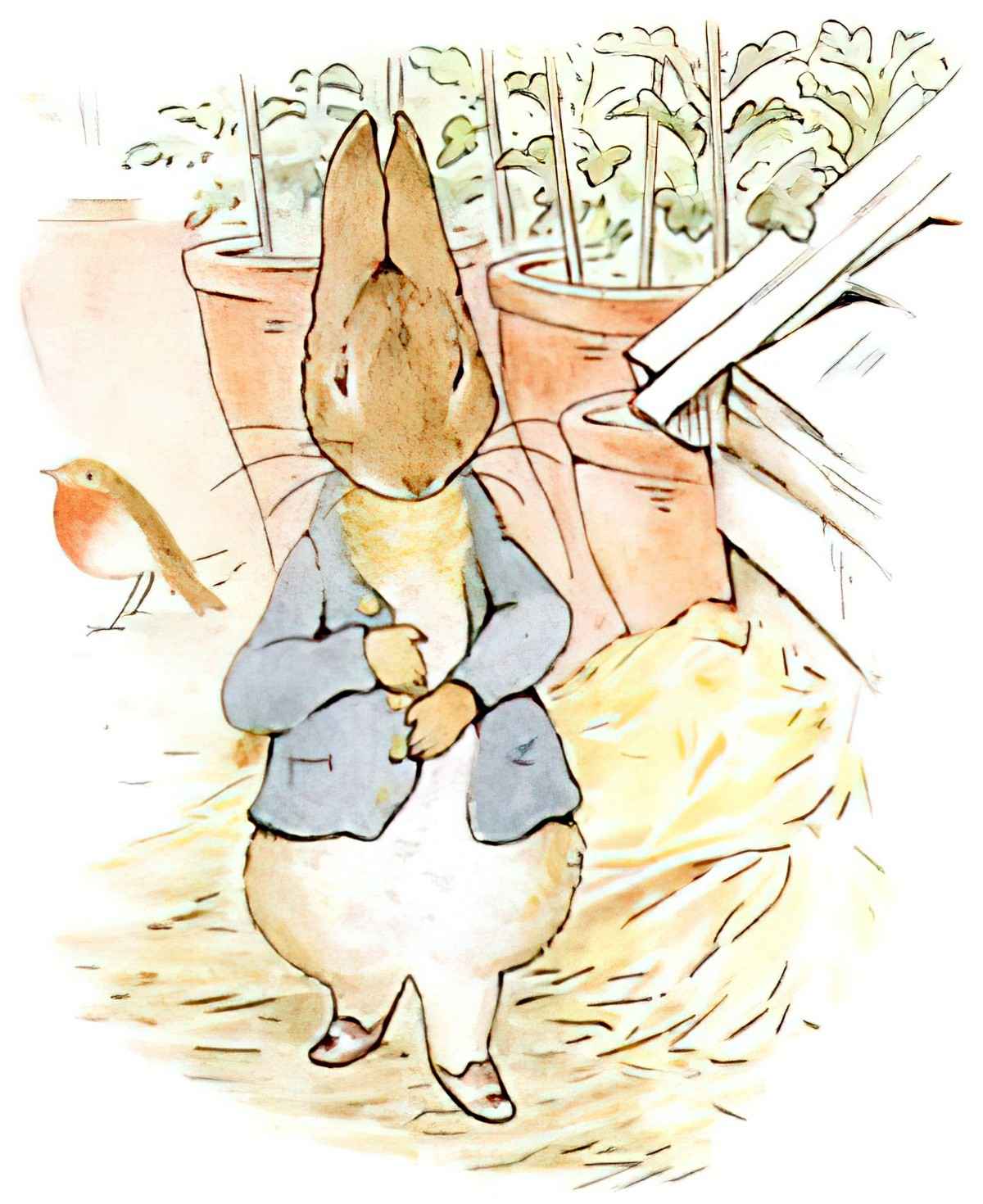

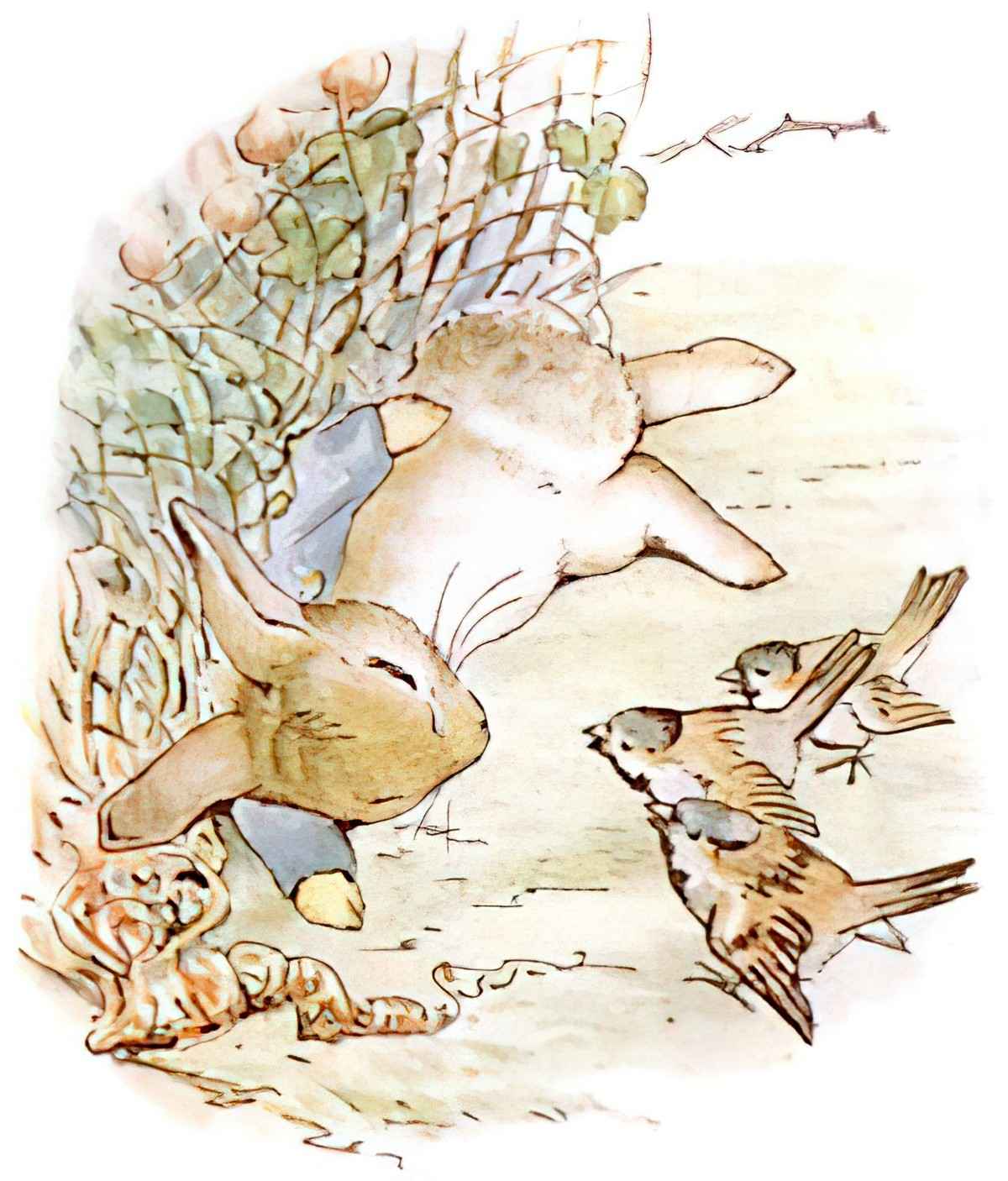

Distortion of bodies and even of objects is a…conventional means by which pictures convey motion. As Peter runs from Mr. McGregor in another picture in The Tale of Peter Rabbit, his head seems almost bullet-shaped, his ears apparently held down by air resistance, his body at an impossible slant that conveys great speed.

As Peter jumps out of the window of the shed, the threat of Mr. McGregor’s descending boot is implied by its disproportionately large size.

The convention by which the motion of drops of water is represented by elongating them into a shape they never actually have in the real world appears in the picture of Peter jumping into the watering can.

Yet interestingly, while this teardrop shape is like a backward arrow, we know the movement is away from the point only because we know the convention; Peter is himself a teardrop shape in this picture, but we assume he is entering the watering can, not leaving it—that he heads in the direction his body is pointed toward.

Perry Nodelman

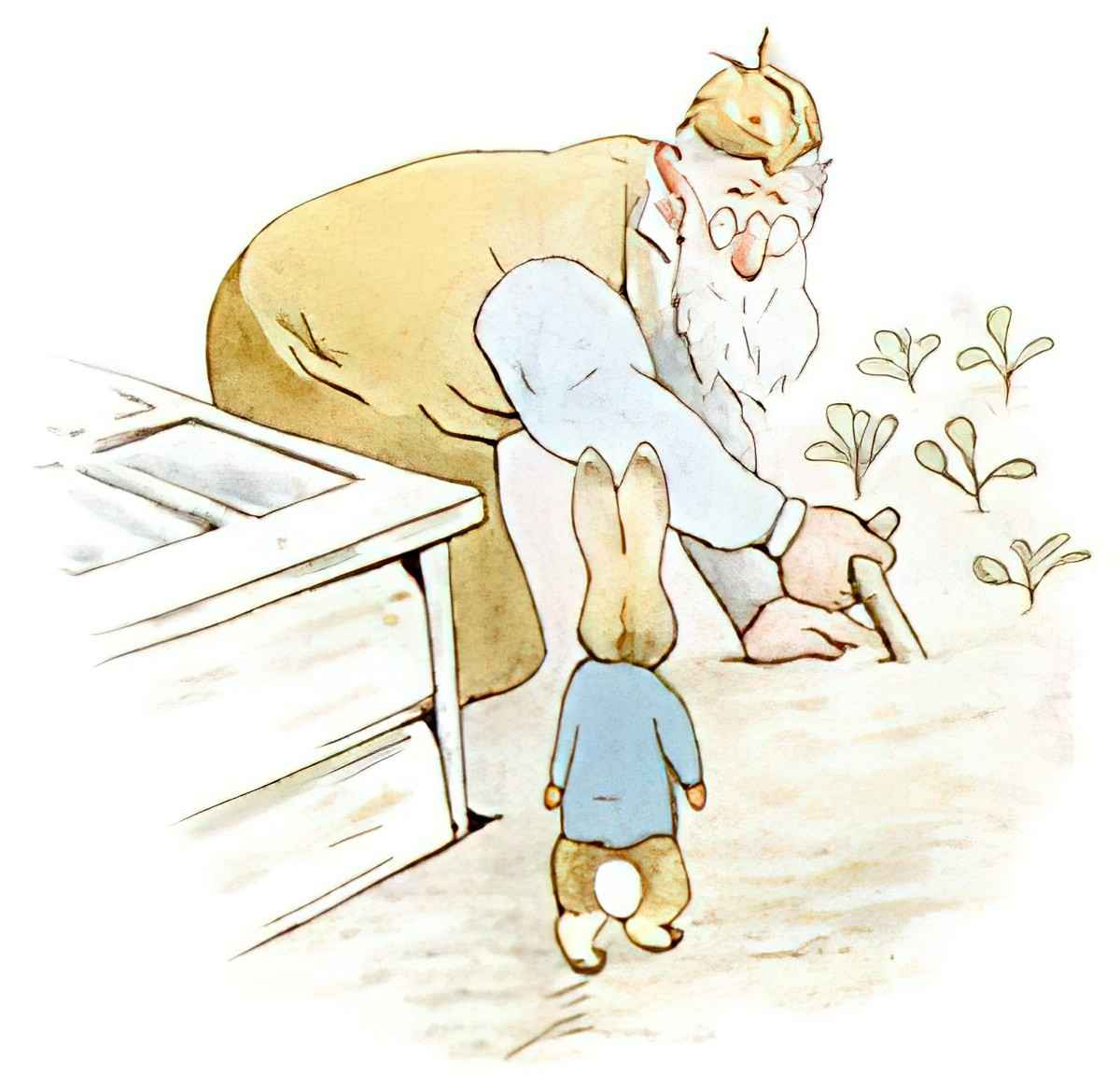

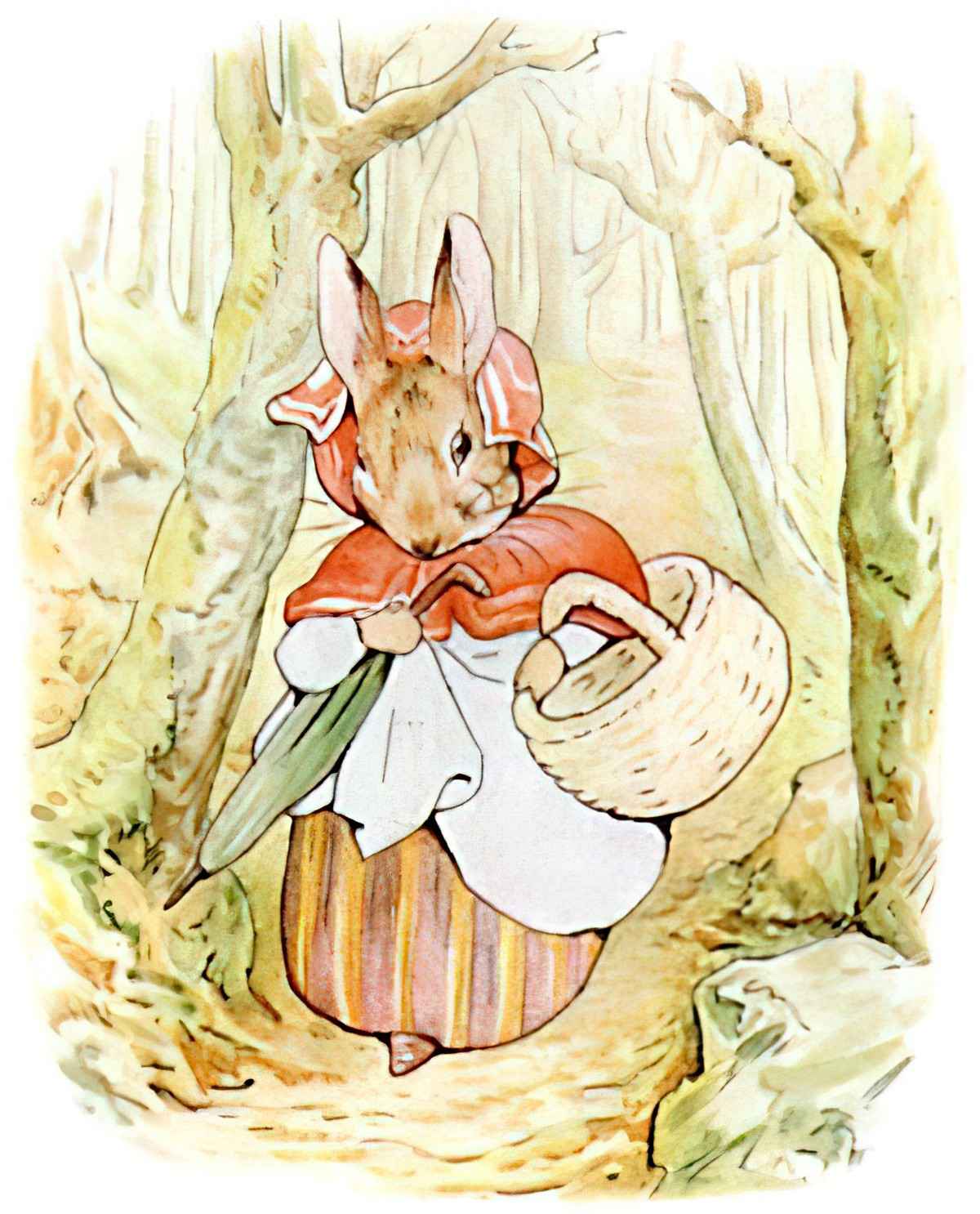

There’s much to be said about the picture below, in which the mother issues instructions.

Gestures

Potter drew animals with human-like gestures:

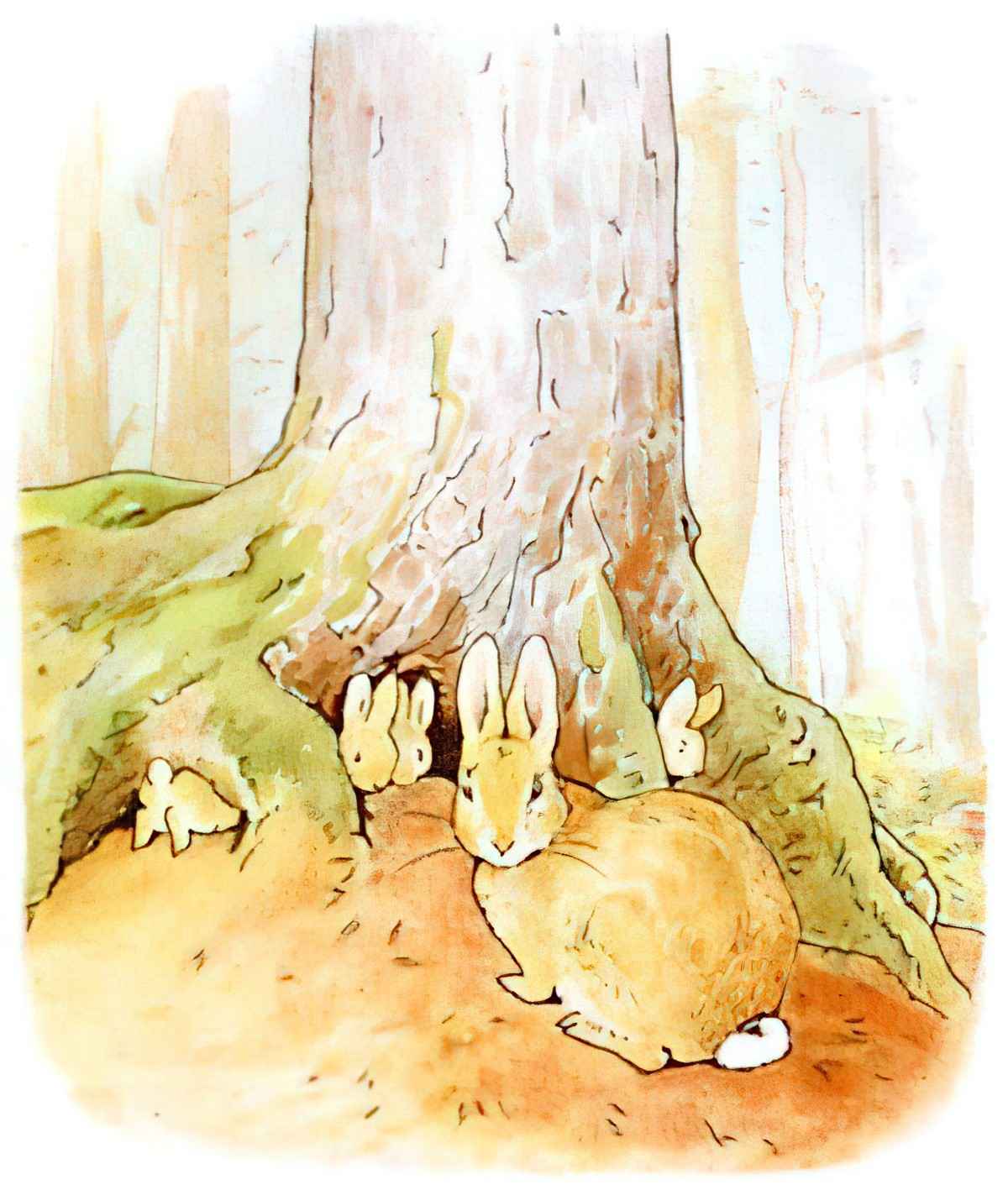

When we see…Peter Rabbit with his back turned to his mother and separate from the cozy group created by his mother and sisters, we assume that his independence is not momentary but typical—as in fact it is.

Perry Nodelman

White Space

Beatrix Potter frequently lets her characters fill the narrower pictures of her small books, especially at moments when they are experiencing strong emotion.

In the first picture for Peter Rabbit, Beatrix Potter shows us rabbits as animals, wearing no clothes, seen with the detachment of observation within a landscape framed by a white border;

but in the second picture the rabbits have been humanized by clothing and stand against a white space that now has the irregular shape of their bodies. We have no choice but to be more involved with these characters, just as we must be intensely involved with Peter later in the book at those moments of intense distress when Potter depicts him against a white background.

Perry Nodelman

Objects Isolated From Their Backgrounds

The relative isolation of objects from backgrounds is often meaningful. Peter Rabbit against a white ground as his mother gives her instructions stands out more than do his three sisters in the same picture, who appear against the background either of their mother or of each other; in the next picture they blur into a hazy background, while Peter is separated from the ground by heavy black lines. Both these pictures make clear which of these rabbits we are supposed to be interested in. According to Graham Collier, “the heavier the weight of a line, the more frontal dominance it and the surrounding area will have“.

Perry Nodelman

Perspective In Peter Rabbit

[A]s Peter’s mother gives her children instructions, we see Mother’s and Peter’s fronts, the girls’ backs. We know whom we should be paying attention to already, even though Peter has not yet become the focus of the text. In fact, the only time we are positioned in a way that lets us see the front of the girls is the last picture of the book, at the one and only moment when they actually do something interesting.

We see Peter from the front throughout the book, except for the two occasions when we see past his back to a sight that alarms him, in both cases Mr. McGregor.

Throughout the book, furthermore, we see Peter from below or head on when he feels in command; but when he overeats we see him lying against the ground, from above; and the same thing happens when he is caught in the netting and nearly gives up.

Perry Nodelman

The Significance Of The Shoe

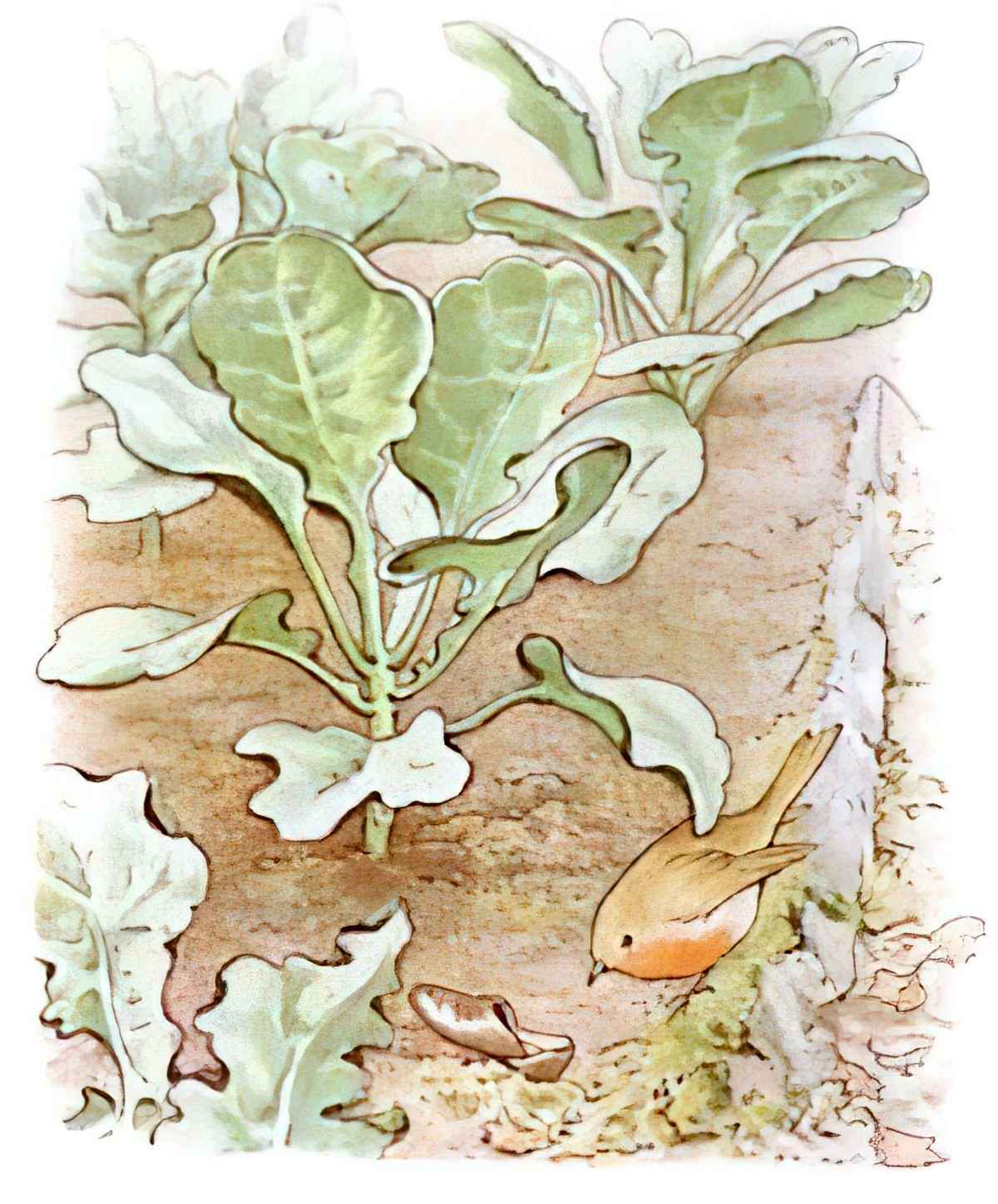

[The most important decision of any illustrator of fiction is that of “which of all the possible moments of choice are the ones that are most significant in terms of contributing to the reader’s understanding of the text and of reinforcing the emotional effect sought by the author”. […] [W]hat is not shown can be as important as what is. Beatrix Potter accompanies the information that Peter Rabbit lost one of his shoes not by a picture of him without the shoe but by a picture of the shoe without him.

This human artefact looks singularly out of place as a robin inspects it under a cabbage; its incongruity is firmly established, while a picture of Peter with only one shoe would have made him look funny enough to lose some of our sympathy. […] In Peter Rabbit a picture shows Peter squeezing under the gate, just as the text tells us that he squeezes under the gate.

But the one specific moment depicted is actually only part of a whole complex action, and there is some significance in Potter’s choice of the specific part. She shows us Peter not all the way into the garden but almost—only his back end is still behind the picket; that allows us easily to guess the completion of the action and thus imagine an action that is not actually depicted. The picture shows both how the gate holds Peter back and how he pushes his way past it anyway; a second picture that showed Peter either on one side of the gate in trepidation or on the other in triumph would destroy the perfect balance between fear and aggressiveness that makes this picture an ideal component of this perfectly balanced story. It would also create a different rhythm, a different sort of counterpoint between pictures and words. The numbers of pictures that illustrate a particular episode not only directly convey meaning through the choices of moment but indirectly add to meaning by assisting in the creation of rhythm.

Perry Nodelman

Almost… But Not Quite

Almost every picture in Peter Rabbit shows a moment toward the end of the actions implied by the text but not at the very end: Peter almost under the gate, but not quite, Peter about to eat a radish, but not quite.

How The Picture Sequence Creates Suspense

It’s all about the pacing.

That establishes a rhythmic pattern of relationships between words and pictures. Our first glance informs us of the isolated moment we see in each picture; then, as we read the text, we move backward to what came before that moment, through the moment again as the text describes it, and then beyond it as the text move beyond it; then we return to that moment again as we peruse the picture a second time.

First we see Mrs. Rabbit walking through the woods; then we are told how she got herself ready to walk through the woods, walked through he woods, and bought baked goods,

and then we go back and see her walking through the woods again. Since the action shown by the picture comes at some point after the beginning of the action as described by the text, we read the text in some anticipation: when will we come to the moment of that picture? Because the action described by the text always moves beyond the picture, our close look at the picture creates a retardation, a backward movement that builds tension and thus suspense. Since the same sort of pattern recurs on almost every opening of the book, a strong contrapuntal pattern develops.

Perry Nodelman

More on pacing in storytelling

STORY SPECS OF PETER RABBIT

- The Tale Of Peter Rabbit was written for five-year-old Noel Moore, son of Potter’s former governess Annie Carter Moore, in 1893.

- The story was revised and privately printed by Potter in 1901 after several publishers’ rejections but was printed in a trade edition by Frederick Warne & Co. in 1902.

- The book was a success, and multiple reprints were issued in the years immediately following its debut. It has been translated into 36 languages.

- With 45 million copies sold it is one of the best-selling books of all time.

COMPARE WITH

Is there an animal-protagonist picture book on the planet that hasn’t been influenced by Beatrix Potter? Potter is the great-grandmother of most modern picture books. Remember, Potter insisted on small, childlike sizes of books. So any imprint which produces small versions of books has Potter to think, from the miniature Little Golden Books to the Ladybird books.

Animals wearing clothes as paper dolls

Below is an illustration by Virginia Albert, an American illustrator who based her works on those of Beatrix Potter across the Atlantic, clearly influenced by The Tale of Peter Rabbit. This is Albert’s rabbit Upsetting Three Plants from a work called The Tale of Peter Rabbit, 1916. The works are so similar that these days there would be copyright issues.

Nodelman and Reimer compare Peter Rabbit to another of Potter’s creations, Jeremy Fisher, who tends to be another of Potter’s best-known characters:

Like human children, Peter Rabbit is torn between the opposing forces of his natural instincts and the societal conventions represented by his mother’s wishes. Despite his relative maturity, Mr. Jeremy Fisher is equally torn between nature and societal convention. Furthermore, both Peter and Jeremy have enemies who think of them as animals and, therefore, believe they have a natural right to attack them. Rabbits who steal vegetables from gardens and frogs who get close to trout are asking for trouble. But both Peter and Jeremy behave like human beings, so that their situation is ambiguous in ways that allow these characters to express common adult ideas about the nature of of childhood. The same might be said of the bat protagonist of Kenneth Oppel’s Silverwing. The theme of half-human, half-animal characters also appears in Pullman’s His Dark Materials books, in which the citizens of Lyra’s world have ‘daemons’, physical manifestations of their inner selves that appear in the form of animals. In Applegate’s Animorphs series, similarly, each of the central characters is able to transform itself into different animals.

The Pleasures Of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

WRITE YOUR OWN

There are many reasons for writing a children’s story with an animal protagonist rather than a human one, and it’s not just for the cute. The trick is to create something new without it being mawkish.

Be careful of being cute in children’s stories. Cut is not authentic. That’s the adult commenting on children.

Joy Cowley

FOR FURTHER CONSIDERATION

120 years later, a TikTok trend describes what Peter Rabbit already discovered — lettuce has a soporific effect (?).

TikTokers Are Guzzling Boiled Lettuce Water To Help Fall Asleep & Science Says They’re Right at Pedestrian TV