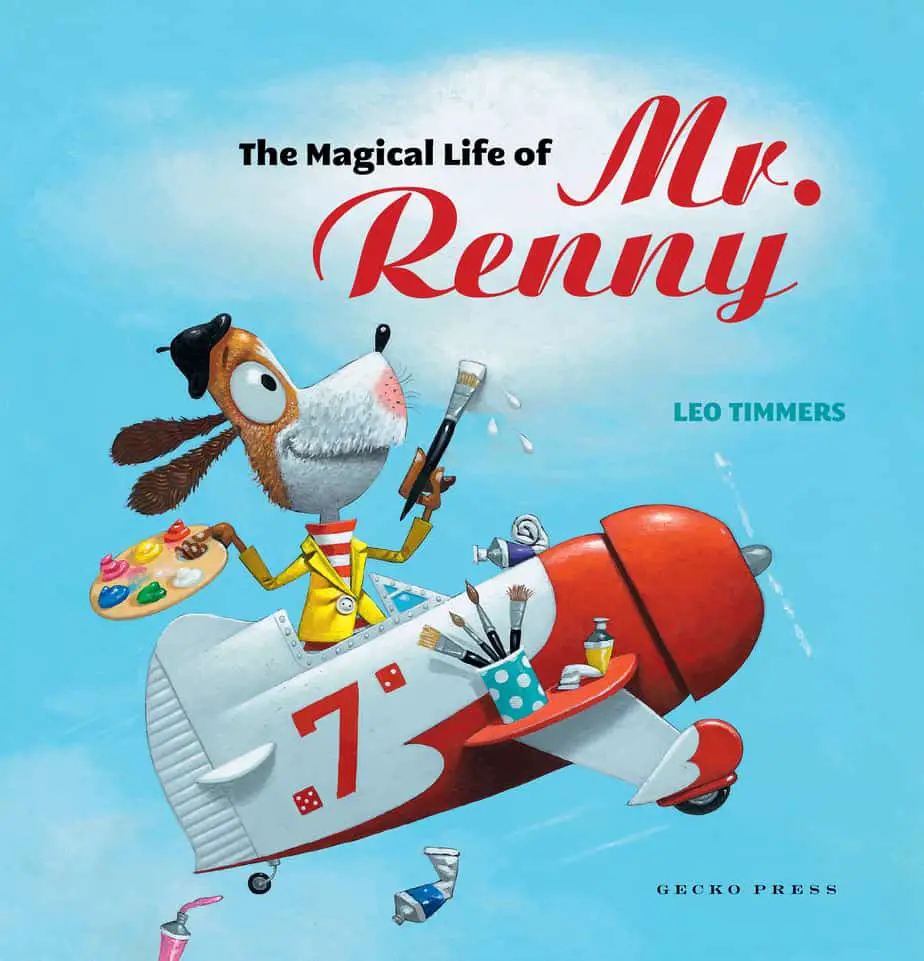

The Magical Life of Mr Renny by Leo Timmers is a modern Magic Paintbrush story in which a central dog character can paint anything he likes. Timmers adds a romantic subplot.

PLOT OF THE MAGICAL LIFE OF MR RENNY

A ‘starving artist’ (represented by a dog called Renny) can’t sell any paintings at the market. Everyone just wants to buy fruit and vegetables. Wishing he could eat the picture of an apple he has painted, a mysterious stranger turns up and tells him that if he were to take a bite of his apple painting, all of them would spring to life. Sure enough this happens, Renny is no longer starving and embarks on a lifestyle of rampant consumerism until an attractive female rabbit turns up wanting to buy one of his actual paintings. Obviously wanting to impress the cute rabbit, Renny renounces his ability to turn paintings into real-world objects and presumably lives ever after, but as a successful artist this time, because Rose the fruit seller has suddenly become interested in Renny’s paintings, which attracts the attention of all her customers.

As an adult reader I do take issue a little with this plot resolution. I’m always a little uncomfortable when a female character (usually dressed in pink — this one also wears high heels, carries a handbag and wears an apron) turns up in what is essentially a male story with her main function being as a love interest. Of course, we’ve all grown up on Warner Brothers/ Looney Tunes cartoons and may not even notice this happening — my daughter certainly doesn’t. So she loves the story without reservation. It’s possible that the author has no such intention for the character of Rose, but my suspicions are aroused when I see female characters depicted as so obviously ‘feminine’, who with few troubling words are able to completely change a male character’s life direction.

WONDERFULNESS

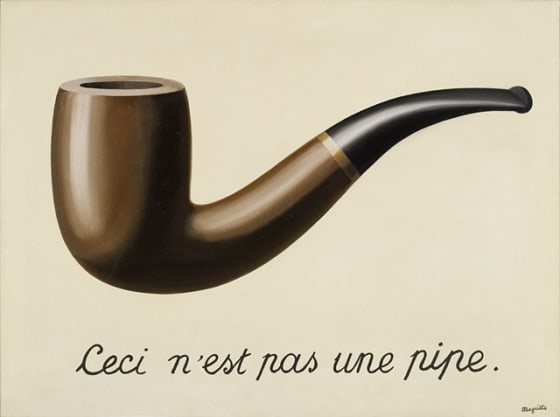

The book opens with a picture of an apple with the caption ‘This is not an apple’. Turn overleaf you’ll read, ‘It’s a picture of an apple’. This is a reference to the art of René Magritte, whose most famous image involves a pipe:

Adult readers will pick up the reference; children are less likely to but it doesn’t matter — the concept is now introduced, and when they do happen upon the René Magritte image, they will be familiar with the concept. I suspect this is the concept that started the whole story, in fact.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION OF THE MAGICAL LIFE OF MR RENNY

Leo Timms is trained in graphic design (rather than in, say, fine arts) and I’m starting to be able to pick it, even before I read about the author on the back flap. It seems a high proportion of men come to picture book illustration after a background in graphic design or animation, and this may help to account for the disproportionate number of male illustrators winning the top awards, because if you read any jurors’ commentaries you will see that they tend to admire is use of white space/negative space, page layout and use of line. (Of course, plain old institutionalised sexism may well play a role in the prize-winning gender divide too.)

Back to the wonderful illustrations in hand, this book is a wonderful example of negative space used to great effect.

First, a white background can make a bright colour palette really pop. On the other hand, a bright colour palette such as this can almost require a lot of white space in order to work. Second — a technical issue — picture books with white space allow for simple black text on a clear background, leading to ease of reading. I’m constantly amazed when I see experienced publishers producing picture books which overlay dark text on dark backgrounds or (more rarely) vice versa. (It’s probably to do with colours printing differently from how they look on screen, but still.) In other illustrations, white space highlights object which lead the eye across the page.

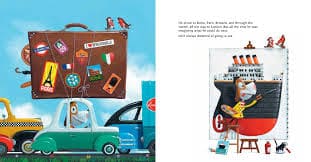

The illustrations themselves seem to gleam. And the nice thing about illustrating for children is that you can make full use of visual hyperbole: When Renny goes on holiday his suitcase is enormous, filling up most of the page. Timmers knows how to play with proportions to comic effect.

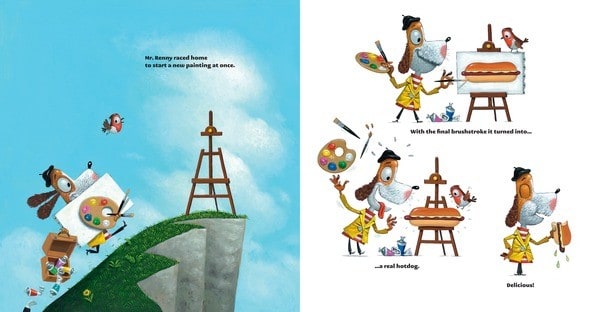

Here is Mr Renny at his usual painting spot, perched on the edge of a precipitous cliff. Metaphorically, Renny is in a financially precarious position.

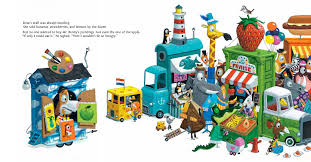

The pictures are detailed enough that more will be discovered on each re-reading: A cigarette butt dropped on the ground (interesting given modern anti-tobacco sentiments), a goat looking horrified as eggs fall from a basket, a copy of The Titanic propped up against the easel as Renny paints a ship (a foreboding image). A little red bird who appears in most images is soon joined by another little red bird who together create an entire unmentioned subplot. (The real bird looks very dejected once its new mate turns back into a painting.)

STORY SPECS OF THE MAGICAL LIFE OF MR RENNY

First published in English in 2012 by Gecko Press, the translation was funded by the Flemish Literature Fund, so I’m only guessing the original language was Flemish.

The book is a larger-than-average square shape which allows the reader to fully appreciate the illustrations. The white space seems even larger when the book itself is big.

COMPARE WITH

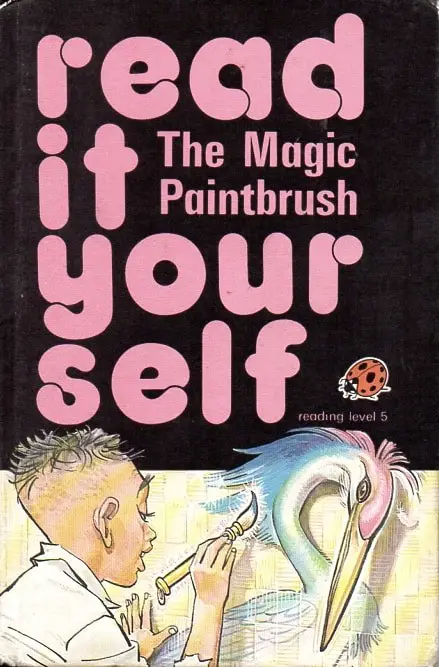

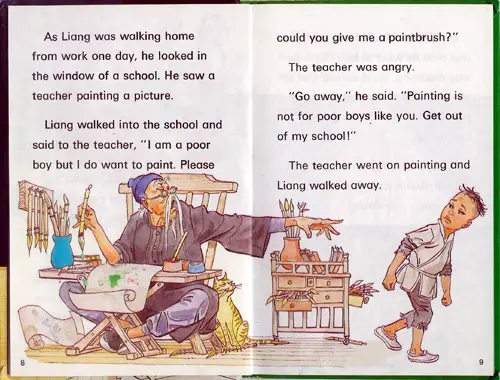

There is a classic Chinese tale translated into English as ‘A Magic Paint Brush’ or ‘The Magic Paint Brush’ about a poor painter whose fortune changes when his paintings come to life. There is a Ladybird Read-it-yourself version, which is probably my daughter’s favourite of all the Ladybird Read-it-yourself books on the shelf.

The idea that the world is ‘painted’ into being is an old and widespread idea, probably as old as brushes themselves.

Timmers’ story also reminds me of the simple and effective story app by Bo Zaunders called The Artist Mortimer (available on the App Store). In both instances paintings intersect with the real world.

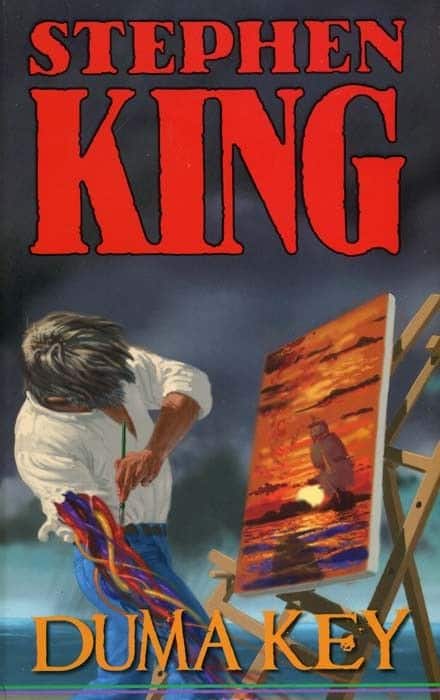

Then there is Stephen King’s Duma Key, in which our main character Edgar suffers a life changing accident and heads to the island of Duma Key to recover, discovering a painting ability that turns him into a local celebrity. But the things he paints are more than his imagination and the island claims lives.

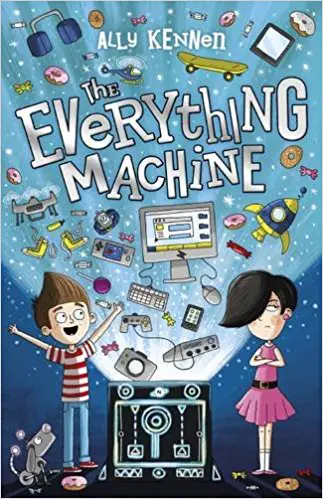

The modern equivalent of a magic paint brush may be the 3D printing machine, as explored in The Everything Machine by Ally Kennen.