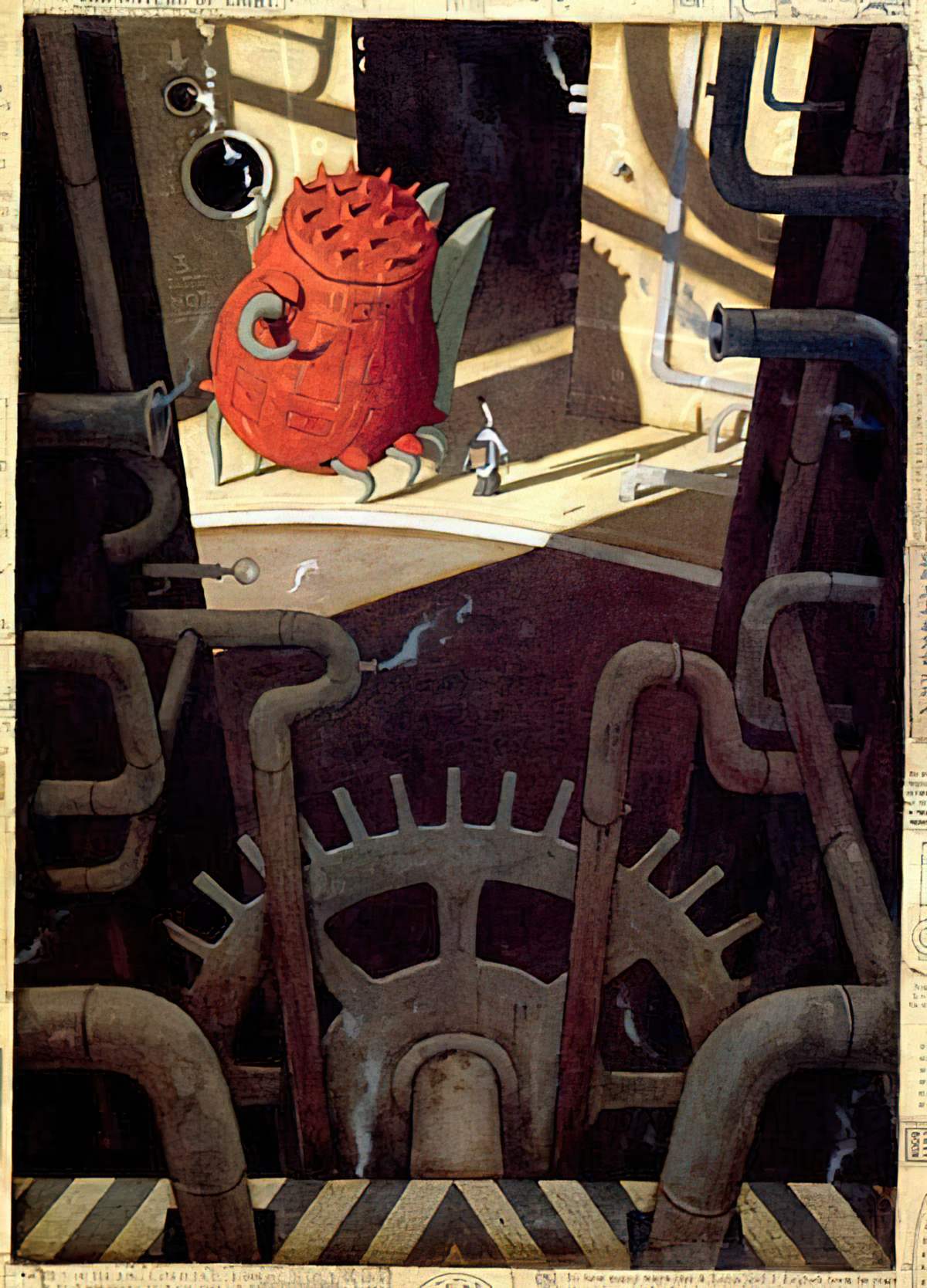

“The Lost Thing” (2000) is an Australian postmodern picture book by Shaun Tan.

Interestingly, the flap copy manages to describe the theme in a metafictional kind of way:

I guess you want to know what this book is about, just by reading this cover flap. Fair enough too; time is short, lives are busy, and most smart, thinking people have better things to do than stand around looking at picture books about some big red thing being lost in a strange city…

marketing copy

This is basically a critique of people wandering through life not noticing things.

The narrator’s parents are too busy keeping up with current events. This reminds me of a Freakonomics podcast Why Do We Really Follow The News?

tl;dr: We follow the news to seem smart. We follow news for entertainment, treating politics like a kind of sport. But does following news really make you smarter, or do you just seem smarter? Are you following the right amount of news, or is your interest in current events perhaps leaving you without time for the small things in your immediate surrounds?

The final page is again metafictive: “And don’t ask me what the moral is.” This is a nod to the fact that children’s books are expected to have morals (even though the best and latest ones don’t at all.)

Readers will bring their own meanings to this story. I’m inclined to see stories as metaphors for autism. The boy’s massive collection of bottle tops is one clue, as is the fact that he is able to notice things others don’t. He’s offered a sign and “I can’t say I knew what it all meant.” There is a popular view of autism as illness, in which an autistic child is expected to learn to fit in with allistics in order to get on in life. Social skills can indeed be learned, but only at the expense of losing that highly individual part of yourself.

More widely, this could be a story about any child with an unusual worldview who, by social conditioning, is gradually forced into adult conformity.

CHARACTER

The first person narrator is ‘the every child’ — at the moment in children’s literature the every boy is white, and a boy, not a girl.

Unusually for children’s book narrators, this is a knowing adult looking back at an incident from his childhood with somewhat renewed insight. This kind of narrator is more often encountered in adult fiction (about childhood experiences) and is probably the thing that makes this story feel like a crossover book. Like other work from this artist, The Lost Thing is not a children’s book, per se. It’s more of an art artifact, or a coffee table book.

I say ‘somewhat renewed insight’ because the narrator admits on the very first page that he has forgotten a lot of stories so he’ll just tell this low-key one instead.

Pete is your stoner sage archetype who ‘has an opinion on everything’. (He seems a bit stoner because he puts ‘man’ at the ends of his sentence.) I’m thinking Harris Trinsky from Freaks and Geeks. TV Tropes calls this the Erudite Stoner.

Some stories subvert the trope. You might have some stoner dishing out advice that’s counterproductive. (E.g. Little Miss Sunshine.)

What’s Shaun Tan done here? While Pete’s advice isn’t total nonsense, it feels about as deep as a Facebook meme. Tan is definitely spoofing the archetype: “He paused for dramatic effect”.

The parents are a boring middle-aged couple who are depicted staring at the TV. The message here is that when we become absorbed in media we stop noticing things going on around us, even though they’re really obvious. And the red thing is, ironically, really obvious. It’s huge. It’s red. When you (the reader) look at that thing you can’t help but wonder what it’s for and what it does.

SETTING OF THE LOST THING

This world is a bit steampunk. It’s full of contraptions that we don’t recognise (including the lost thing itself.)

This is a world from perhaps the 1980s, when intriguing people and advice could be garnered from the back pages of a newspaper. (I’m probably the last generation to know what sorts of things were found there.)

The television is the old cathode ray tube type which is way more fun to draw than a plasma screen, and which is dying a slow death in picture books. (For various reasons I chose to draw a CRT TV in my own picture book app Midnight Feast, even though it’s set in the near future. So I understand this completely.)

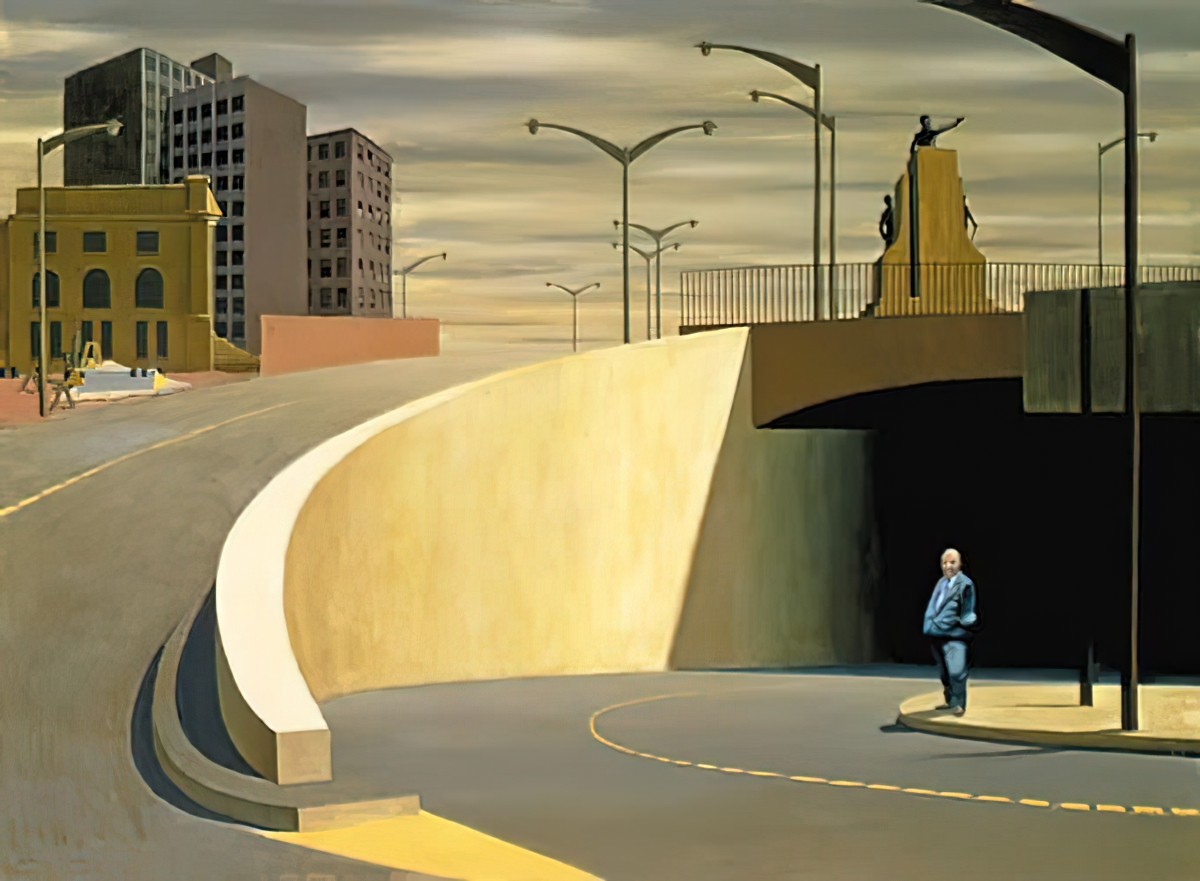

The following image is Tan’s re-imagining of a famous Australian painting by artist Jeffrey Smart. “The Cahill Expressway” painting was influential in 1960s Australia. Forty years later Shaun Tan has used a pastiche of this picture to convey a sense of bleakness.

And here’s the 1959 Smart painting, called “The Cahill Expressway”:

The Cahill Expressway is in Sydney.

This painting has been the inspiration for many Australian artists, and there is even a collection of short stories, all inspired by the painting. (The book is called Expressway.)

I wonder if Smart’s painting was even influential for Colin Stimpson (though Stimpson is not Australian) when he wrote and illustrated Jack and The Baked Beanstalk.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE LOST THING

SHORTCOMING

The boy as every child means that the shortcoming/need is cast upon the reader: We are all too busy fitting in to notice little things (and also, probably, very big things!) that are right under our noses. We need to stop and look at world. This is metafictive in a less obvious way; picture books require readers to slow down and study the pages in a way no other medium really does. You won’t be able to read this picture book properly unless you linger on the illustrations.

DESIRE

The boy wants to know more about this big red thing, and know that it’s happy and safe.

OPPONENT

The natural opponent is wider society, disinclined to look after the odd things that don’t fit anywhere. This ‘society’ is personified by the parents, who need the Lost Thing pointed out, and even when it’s pointed out, they take no real interest in it.

PLAN

He brings it home and houses it in the shed, but he’s worried his parents are going to find it.

So when he happens upon an advertisement in the back of the newspaper he goes on a mission to find out where this thing fits in.

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle is the mythic journey that the boy must embark upon after he finds the sign with the squiggly arrow. It’s a battle finding out where the Lost Thing fits because he has to work it out himself.

ANAGNORISIS

The anagnorisis is symbolised with a literal door open, and a big red button. The boy learns that there is a whole other world full of non-conforming things right behind the boring veneer of society.

NEW SITUATION

The unhappy ending is that this boy is an adult now and can hardly remember any of the amazing things he knew of as a child.

RESONANCE

The idea that adults don’t pay enough attention once we monotropically become sophisticated workers with specialised skills is not new since the smartphone, in case you were wondering. It’s an old idea and I doubt it’s going anywhere soon.

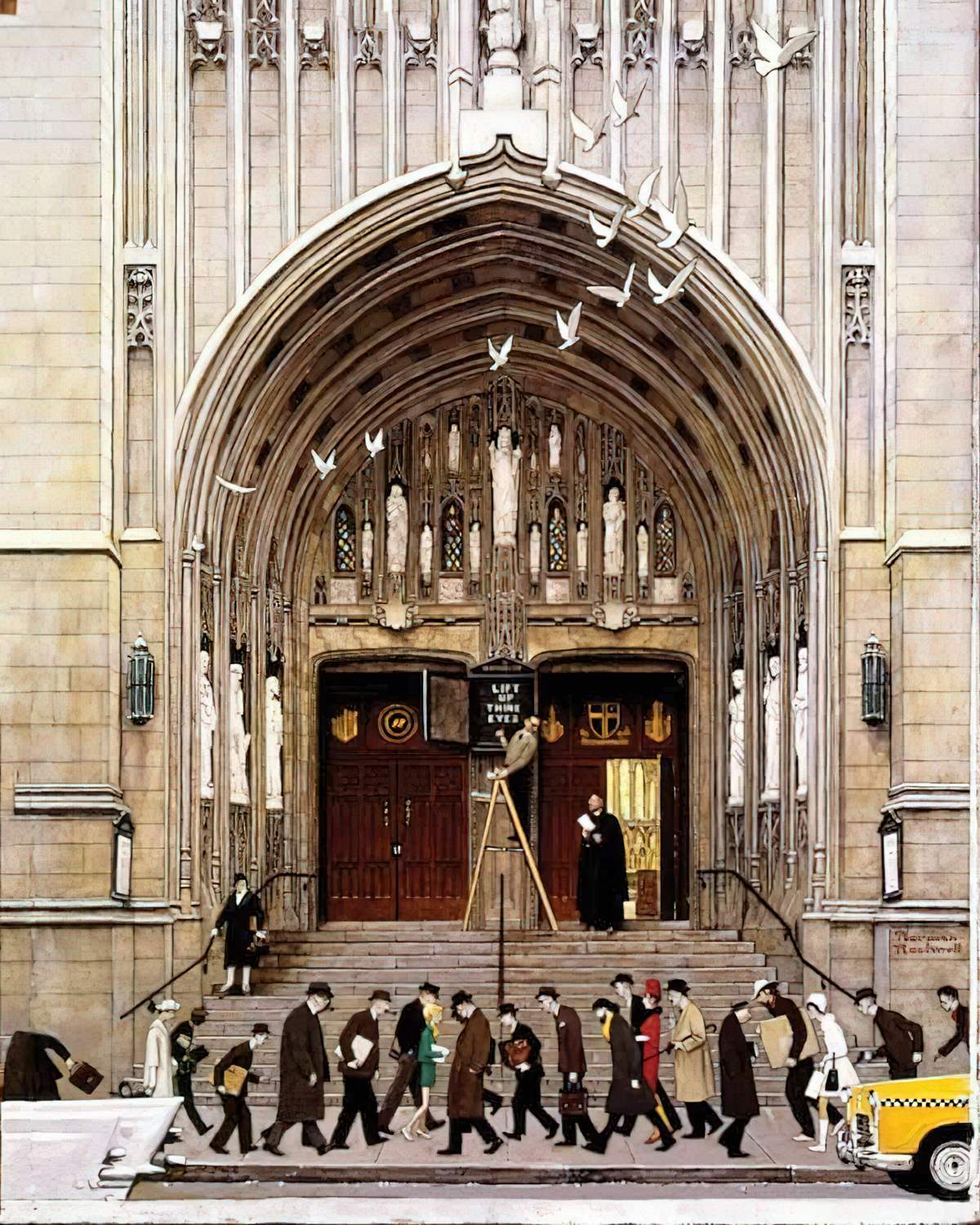

The following illustration is from 1966.

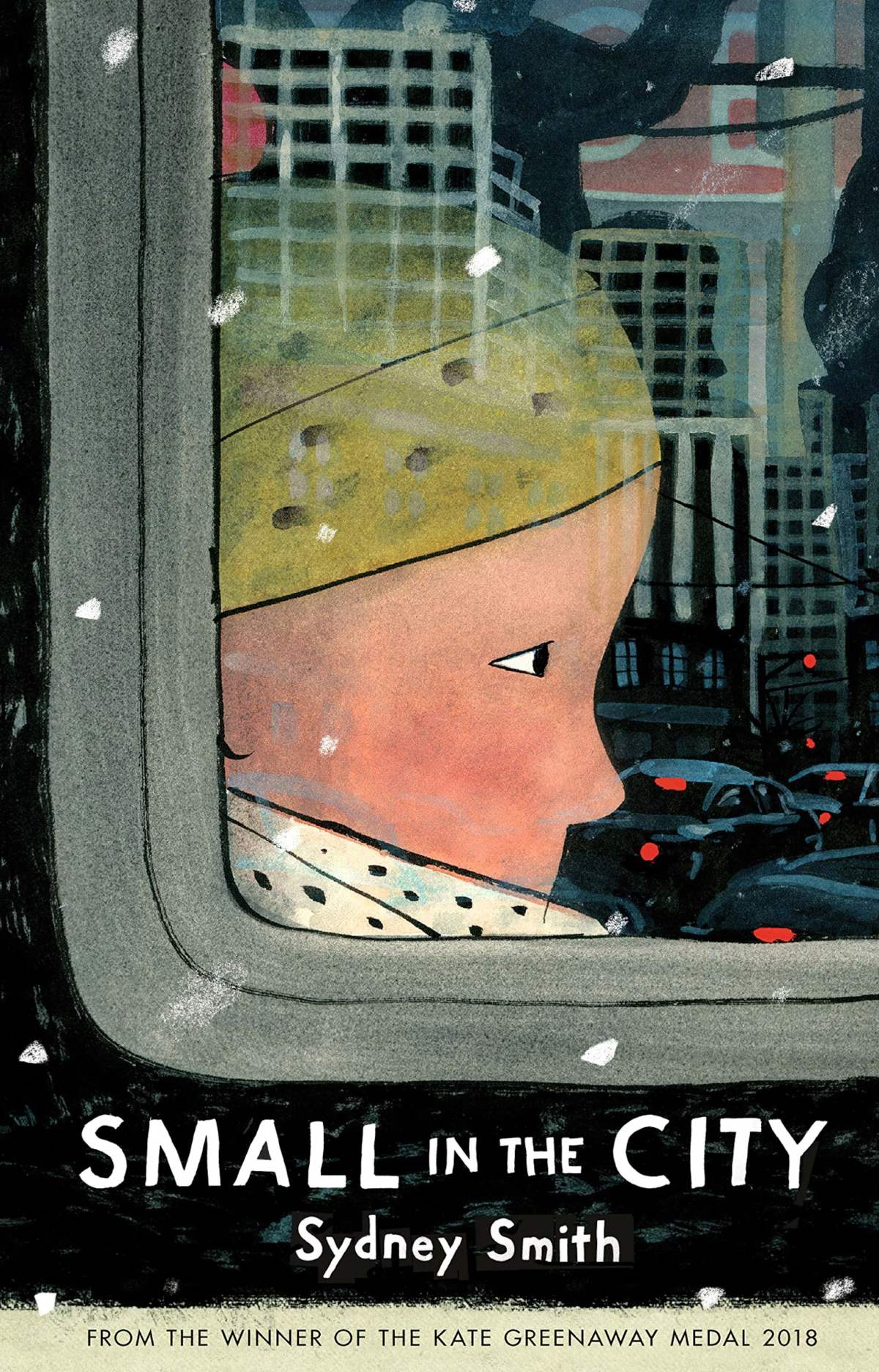

I know what it’s like to be small in the city…

Being small can be overwhelming in a city. People don’t see you. The loud sounds of the sirens and cyclists can be scary. And the streets are so busy it can make your brain feel like there’s too much stuff in it. But if you know where to find good hiding places, warm dryer vents that blow out hot steam that smells like summer, music to listen to or friends to say hi to, there can be comfort in the city, too. We follow our little protagonist, who knows all about what it’s like to be small in the city, as he gives his best advice for surviving there. As we turn the pages, Sydney Smith’s masterful storytelling allows us to glimpse exactly who this advice is for, leading us to a powerful, heart-rending realization…