Last year marked the 40th anniversary of William Steig’s The Amazing Bone. This is remarkable because it feels, in some ways, like a much more modern picture book than that. This is all to do with Steig’s voice. Pearl is at no point mortally afraid. We know and she knows that this is a storybook world in which good will always triumph. Steig writes knowingly to the reader — we all know this is a modern fairytale. So when he writes of the baddie, ‘He wore a sprig of lilac in his lapel, he carried a cane, and he was grinning so the whole world could see his sharp teeth’, he is holding nothing back from the reader.

Steig’s distinctive voice is also achieved by his choice of vocabulary, which is by turns highly specific against ‘fairytale familiar’ (as above):

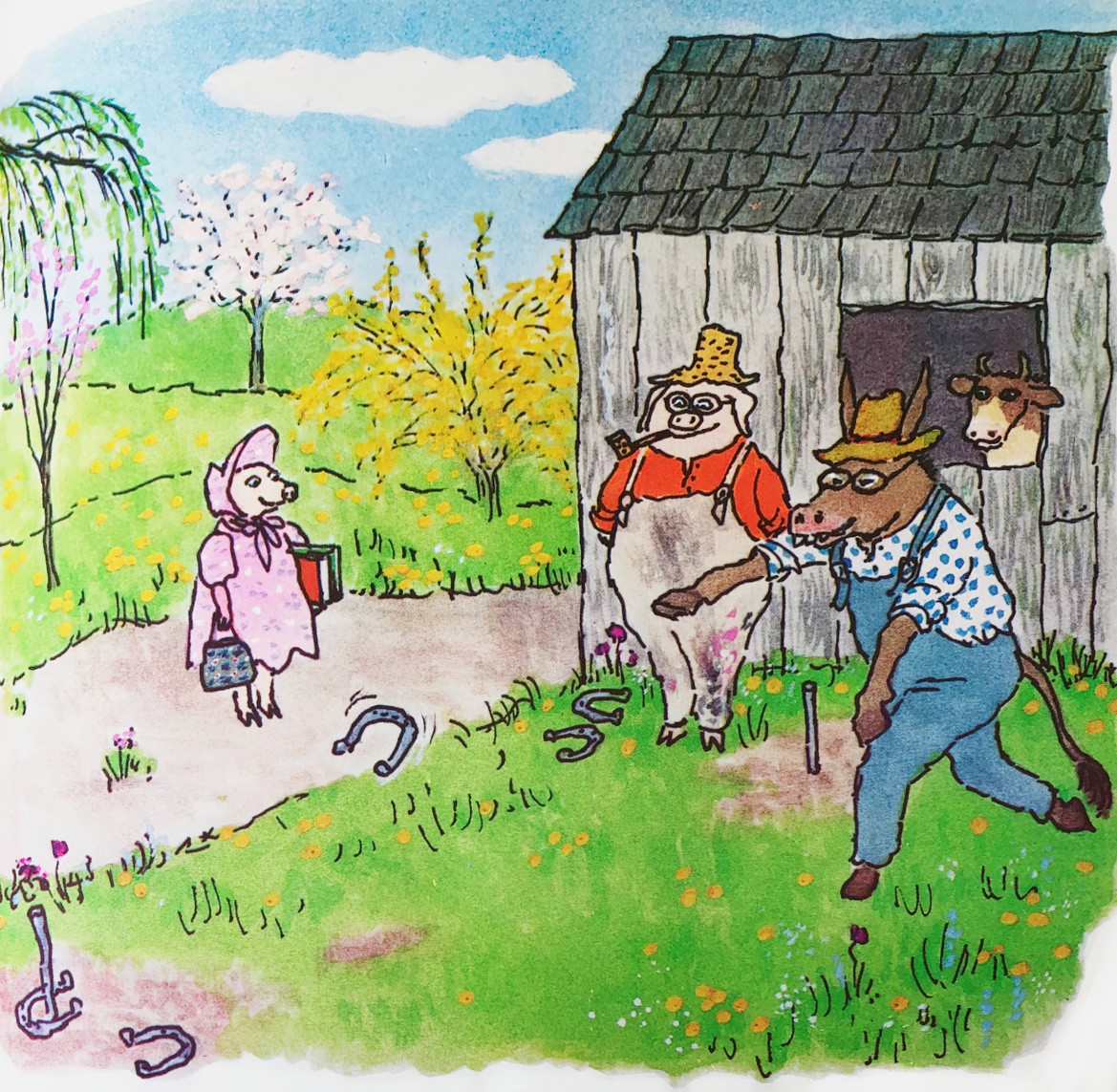

On Cobble Road she stopped at Maltby’s barn and stood gawking as the old gaffers pitched their ringing horseshoes and spat tobacco juice.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE AMAZING BONE

SHORTCOMING

Pearl the pig is an Anne of Green Gables character — dreamy and optimistic despite the hardships she endures.

Steig opens the story with, “It was a brilliant day, and instead of going straight home from school, Pearl dawdled.” This will remind you of Little Red Riding Hood, no doubt. The Grimm Brothers transcribed that tale at a time when, as properties of men, women and girls were required to be inside the house. If anything happened to them while they were enjoying the outdoors, it was their own damn fault.

As a pig, she is also delicious. Even in 2017 we’re getting a whole heap of ‘I Love Bacon’ memes through our feeds, so most people can relate to a pig’s predicament. Not that children will be thinking along these lines at all. But to this modern reader that is her main shortcoming in the story — she is delicious to foxes. She becomes a victim through no psychological or moral shortcoming of her own.

It does pay to remember, though, that this was not the intention in early iterations of the Red Riding Hood category of tales, which existed to punish girls for stepping outside, and blamed them for the evil predilections of men, while also being saved by them.

DESIRE

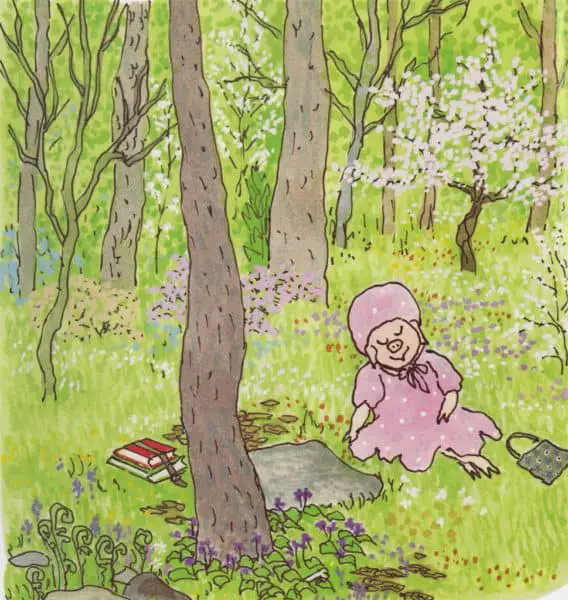

Pearl wants to enjoy her day outdoors. Steig gives us quite a lengthy introduction — longer than modern picture books allow for — in which we see her ‘dawdling home’ sequence.

Finally we see her at her most relaxed, sitting in the grass and dreaming.

Note the pacing of this first section of the story (encompassing Pearl’s shortcoming and desire and her ‘normal life’ (which we know is about to be disrupted. We see one scene per page. In fact, this scene is a double spread. Later, as the excitement picks up Steig will put two pictures on each page. This is the illustration equivalent of using short sentences after long, languorous ones.

ALLY

Pearl’s ally is introduced before her opponent is introduced, which has the useful effect of creating tension in the audience, who will wonder if this amazing bone is really on her side or if it is a fake-ally opponent.

When we meet the bone we also meet the catch phrase of the story: “I don’t know, I didn’t make the world.” This is somewhat metafictive as Steig’s lampshading requires the reader to wonder about the origin of magic in the story. We are reminded not to worry about all that — Steig is taking overt artistic licence to do any unexpected thing he likes. This works very well because of the long history of fairytales. The ones which have survived are not all that ‘quirky’ — they are full of witches and forests and ogres and magic creatures, but not pieces of magic creatures. There is no logical reason for Steig to have written a story starring a magic talking bone and although readers will happily accept a magical witch or something, he gets quite a lot of mileage out of the fact that this bone can talk even though it doesn’t have lips.

PLAN

The bone explains that he has been dropped by a witch and would prefer to live with the youthful, optimistic Pearl, so they set off home. Pearl knows what her parents will say — they’ll say it’s ridiculous that she has a bone which can talk — more lampshading to humorous effect.

OPPONENT

Of course the opponents appear at this point from behind a rock. They are wearing masks from Japanese theatre, which I agree are the most freaky looking traditional masks out there.

The characters with the long noses looks like tengu. They’re a kind of supernatural creature, part human, part bird or prey.

The middle creature in yellow might represent a hannya, This character is possibly the most ridiculously misogynistic of the Noh masks, expressing the fury of a woman turned demon through jealousy and anger and who revenges by attacking.

(These days I feel the V for Vendetta Guy Fawkes mask has supplanted traditional Japanese masks in the West when it comes to freak value. Ghostface is also very scary — perhaps we will not be seeing these in a picture book anytime soon.)

These masked creatures are not the main opponent, however. They are just part of the landscape, reminding Pearl and reminding readers that even in an environment which looks beautiful and safe, evil can jump out from anywhere. These characters are easily scared off by the talking bone in Pearl’s handbag, which they are trying to steal from her, and although we never see their identities, if you look closely at the illustration you’ll probably agree with me that these ‘highway robbers’ are meant to be dogs. Dogs, compared to canines from the wild, are usually fairly hapless criminals, both in real life and in storybooks.

This is when the real opponent turns up. This time the bone’s talking won’t spook him. We know it won’t spook him because of Aesop. Foxes are smart, unlike dogs.

The wily fox was not as easily duped as the robbers. He saw no dangerous crocodile. He peered into Pearl’s purse, where the sounds seemed to be coming from, and pulled out the bone. “As I live and flourish!” he exclaimed. “A talking bone. I’ve always wanted to own something of this sort.”

(Note that Pearl herself is an ironic Aesopian character. Traditionally, we expect pigs to be dirty and gluttonous, but Pearl is delicate and refined. Dr Seuss does a similar thing with Horton the elephant, who would normally break a tree by sitting in a nest. We see Horton’s bulk and don’t immediately expect him to be timid. Young readers learn not to judge characters based on their appearance.)

The fox is a smartness proxy for the audience. Indeed, when I read this story to my daughter she exclaimed, “Oh, I wish I had a talking bone!” just as the wily fox had done in the story.

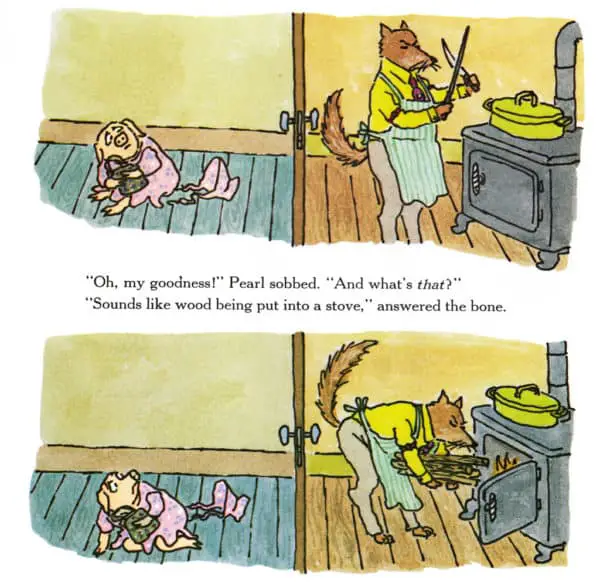

The fox takes Pearl home for dinner, where he plans to eat her of course. He locks Pearl and her bone in the basement.

At this point we wonder how on earth Pearl and the bone are going to get out of their dire predicament. Plotting-wise, this is the difficult part for the writer. The writer must come up with some ingenious plan which surprises the reader.

Humour wise, this is the highlight of the story. Pearl and the bone whisper to one another, which gives a read-aloud narrator some welcome variety — not enough picture books encourage stage whispering — and their conversation is alternately melodramatic versus reminiscent of two girls sitting outside the principal’s office rather than about to meet their death:

“I know how you feel,” the bone whispered.

“I’m only just beginning to live,” Pearl whispered back. “I don’t want it to end.”

“I know,” said the bone.

At this tense point Steig uses a technique called the dynamic frame. The dynamic frame is film-making terminology butis even more common in picturebooks than it is in film. Filmmakers who use dynamic frame change the size and shape of the image on the screen. It has gone out of fashion in filmmaking. You still see it in contemporary films when shooting through doorways, for example, so hat the lighted area seen by the audience is shaped, even though the shape of the screen itself doesn’t change.

For another example of this technique in a picture book see Hyman’s Sleeping Beauty, with views through the arches. In Where The Wild Things Are, the pictures gradually grow in size and then become smaller.

This part of the story will probably remind you of Hansel and Gretel more than Little Red Riding Hood, as the fox cranks up the stove ready for Pearl to go in.

BIG STRUGGLE

Rather lazily, in storytelling terms, Steig’s amazing bone can do magic. It comes out with a number of magical phrases and the fox gradually shrinks to the size of a mouse, retreating into a hole in the wall.

However, it totally works. Steig gets away with ‘rescued by magic’ because of the dialogue. The bone is just as amazed as Pearl at his ability to get them out of trouble, and the joke has been set up earlier with the gag that bones couldn’t possibly talk because they don’t have mouths.

“Well, what made you say those words?”

“I wish I knew, “the bone said. “They just came to me. I had to say them. I must have picked them up somehow, hanging around with that witch.”

It’s the haplessness and the understatement which leads to the humour.

ANAGNORISIS

“You are an amazing bone,” said Pearl, “and this is a day I won’t ever forget!”

This is an uninspiring line but a necessary one. Sometimes you need those lines in stories. I’m going to call it the ‘overt revelation’, but it’s not a genuine one. The fact is, humorous picture books don’t actually need a anagnorisis. We hope that Pearl will not suffer from PTSD. We hope that she will go on just as before, frolicking in meadows and enjoying herself.

The audience does have a small revelation — Pearl was absolutely right about what her parents would say about her bringing home a talking bone. Naive as she is, Pearl does have insight into human behaviour, at least when it comes to her own parents.

NEW SITUATION

The bone stayed on and became part of the family. It was given an honored place in a silver tray on the mantelpiece. Pearl always took it to bed when she retired, and the two chatterboxes whispered together until late in the night. Sometimes the bone put Pearl to sleep by singing, or by imitating soft harp music.

Anyone who happened to be alone in the house always had the bone to converse with. And they all have music whenever they wanted it, and sometimes even when they didn’t.

SEE ALSO

The Amazing Bone: Scrabboonit! from We Read It Like This

THE SINGING BONE: FAIRY TALE COLLECTED BY THE GRIMMS

If you have brothers, you won’t like them any better after hearing this tale.

If you’d like to hear old folk tale “The Singing Bone” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Singing Bone” was published May 2020.