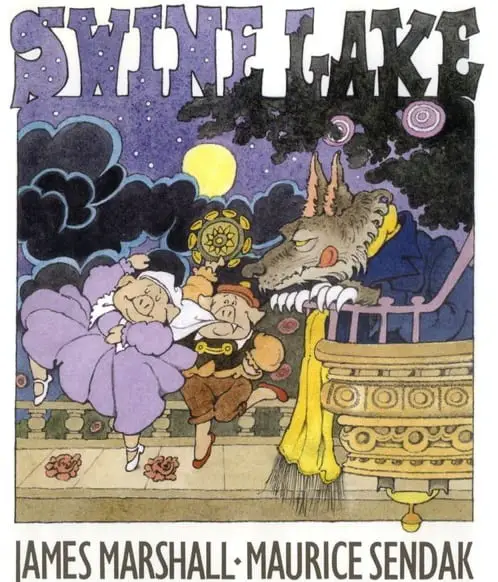

Swine Lake is a 1999 picture book by James Marshall, illustrated by Maurice Sendak. The humour is an example of ‘hero wears a mask‘ transgression comedy.

About the Author and Illustrator

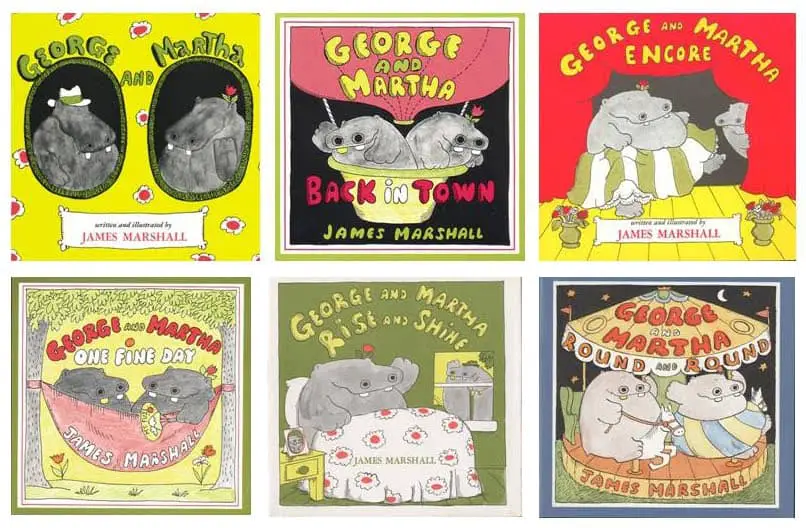

If you’re American, perhaps you’re familiar with the following series:

The author and illustrator of the George and Martha series also wrote other books, and one of those was illustrated posthumously (after Marshall had died, that is) by Maurice Sendak. Even if you’re not American, if you’re at this blog you’ll most definitely know who Maurice Sendak is!

So Marshall died in 1992 of a brain tumour. The powers that be probably weren’t expecting him to die quite so young, and awarded him the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award for contributions to children’s literature in 2007.

Maurice Sendak illustrated James Marshall’s standalone book Swine Lake for publication in 1999. Sendak himself died in 2012, but he was 83 when he died and, lucky for him, he lived long enough to see himself awarded that Laura Ingalls Wilder award, as well as receive an honorary doctorate, the National Medal of Arts and the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, among others. The moral of that story is, if you’re a talented picture book creator, make sure you live to a grand old age if you want to live to see all of your awards.

Let’s talk some more about James Marshall.

Marshall obviously enjoyed reimagining pop culture as animals. He came up with George and Martha while lying in a hammock as his mother watched Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? nearby. He took the characters George and Martha from that, but turned them into hippopotami.

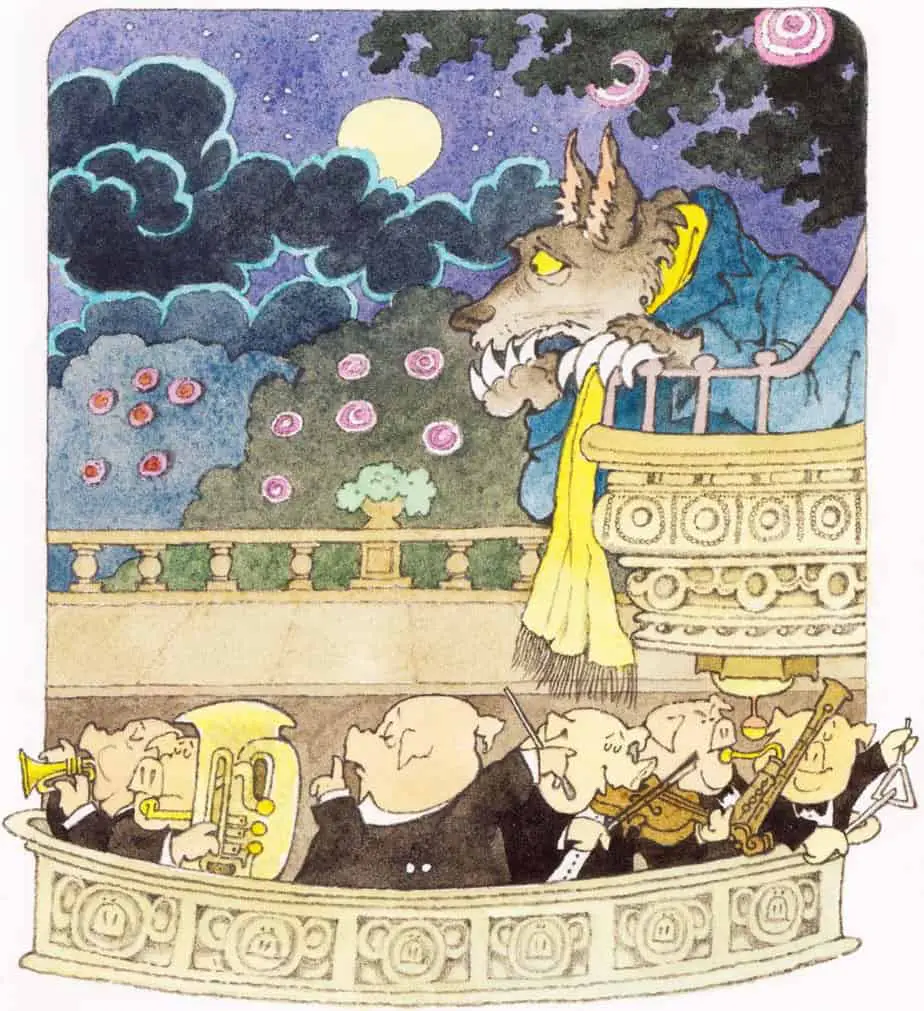

He’s done it again in Swine Lake which, to the adult co-reader, at least, is an obvious pun on the famous Russian ballet Swan Lake, composed by Tchaikovsky. A synopsis of Swan Lake can be found here.

Notes On The Illustration Of Swine Lake

It’s interesting to see that lettering on the cover, in which the block letters incorporate the picture, because it’s become very popular since Photoshop with its layer masks making it so easy to do.

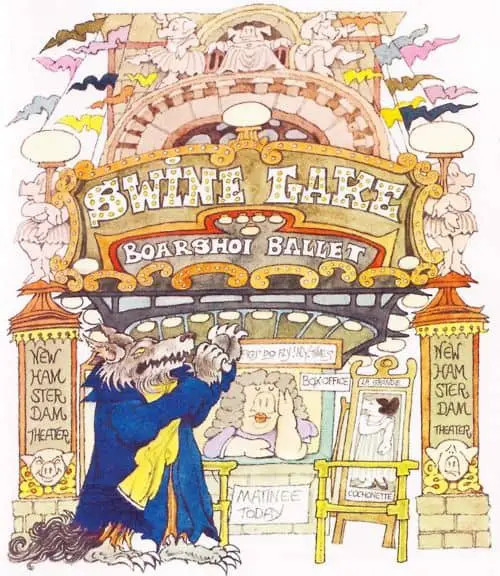

Swine Lake is an example of a picture book in which the intratext is a part of the plot. This page adds to the humour, with a variety of #PigTheaterPuns (let’s make that trend on twitter, shall we?) Later in the book we’ll see the wolf reading the reviews of his own performance, in which the review is part of the illustration.

This is also one of those picture books which includes a subplot running through the illustrations which isn’t mentioned in the text. It’s often a pair of animals which play a minor part, and so it is here with the squirrels who Wolf initially contemplates eating, and who end up laughing at the spectacle of the wolf as dancer. The squirrels know that the wolf is really a wolf even if the pigs don’t. We see them exchange a knowing look on the final page (where there is nothing but a small picture, in true picturebook tradition).

Story Structure Of Swine Lake

Shortcoming/Need

The wolf eats other animals and is ungrateful (for example when offered tickets). He is your typical sociopathic wolf. (Actually, I did hear that wolves are basically ‘sociopathic dogs’.)

Desire

He wants to eat pigs.

Opponent

Is there a true opponent in this story? This is one man’s anagnorisis. Everyone around him is very obliging. The circumstances stand in his way a little — he has no money to buy a ticket.

Plan

He will get inside a performance of Swine Lake because there will be pigs everywhere. He can then have a pig feeding frenzy at an opportune moment. The hitch in his plan is that he has no money for a ticket, but he is saved by circumstance when a rich sow gives him her tickets.

Big Struggle

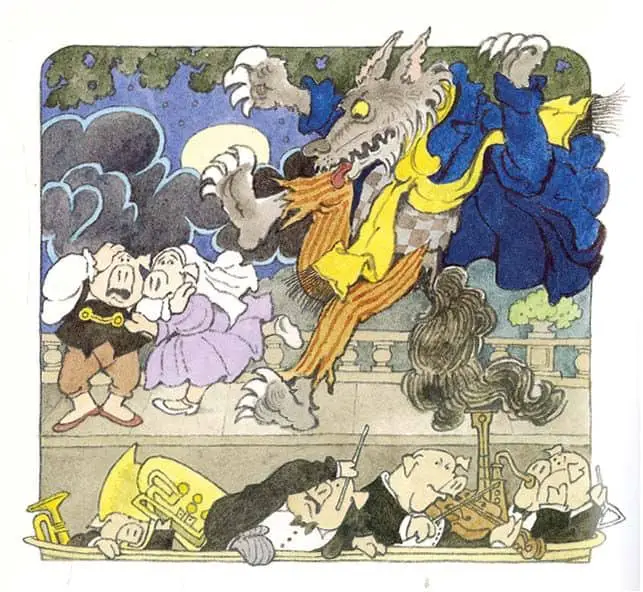

The reader is expecting a big struggle, and this story subverts the expectations. The wolf’s big struggle is an inner one — what has happened to him? He’s so overwhelmed by the beauty of the play that he’s not the same wolf anymore.

In stories where there is no outer big struggle there is always some sort of climactic scene. Here, the author takes the climactic scene from the play and uses that to convey the crescendo of the wolf’s emotions.

Anagnorisis

Wolf realises he loves the theatre, and his love of this art can even keep his mind off more grim matters.

New situation

After reading such wonderful reviews of his own performance he’ll probably keep going to the theatre and trying to get in on the act. The final sentence says, “And he executed a couple of flashy dance steps.”

The Humour Of Swine Lake

A lot of comedic stories are of the type where the hero wears a mask, metaphorical or otherwise. The structure goes like this:

Discontent: the hero is unhappy about something

Transgression with a ‘mask’: peculiar to comedy and noir thrillers (the mask is metaphorical — the hero is trying to pass themselves off as something they’re not)

Transgression without a mask: midpoint disaster when the mask is ripped off — the hero is ‘found out’

Dealing with consequences [Howard Suber writes: “What will the hero do when he discovers his armour doesn’t protect him, that he can be violated — now and in the future? There is only one satisfactory answer: he can pick himself up, dust himself off, and start all over again.”]

Spiritual Crisis: happens in almost every story

Growth Without a Mask [Suber writes on this point: Some people might find it astonishing how many memorable popular films end in violence and death, but the history of drama is filled with them, and it is difficult to find any period that is not filled with them. If death is the ultimate separation, the next worst is the separation of people who love one another…The story that resolves itself in unification is most often a comedy.]

This book is a slight variation on this structure — when his mask ‘came off’ (when he lost himself and flew into the middle of the pigs’ performance to dance) the characters around him assumed he was only dressed as a wolf.

The metaphorical mask he didn’t know he was wearing from the get-go has come off, however: He demonstrates his wolflike bravado when he threatens to chase the squirrels (and then doesn’t), and when he has every opportunity to eat pig outside the theatre (but still doesn’t). This wolf is a lot more at home as a lover of ballet. Now he is free to dance. He also seems to have been freed from his wolflike impulses (though I’ve no idea what he’s going to eat from now on, which is a problem in all of these stories in which a carnivorous animal sees the error of their ways — The Tawny Scrawny Lion is another one!).

Everywhere you look in the illustrations, the more you realise you’re living in pig-land. The banister at the theatre has been carved with pig faces, for example. Is this a visit to Pig Town for the wolf, who would surely be spotted right away if he’d really gone to such a part of town, or is this Wolf’s hallucination? We’ve already seen that he is scrawny and sick in bed. He could be dreaming the whole thing.

Another word on the humour: A lot of picturebook humour derives from stock characters which have been inverted. In this case, a wolf loves ballet rather than eating meat and ballet dancers are shaped like pigs rather than the svelte figures we’re used to. In other words, it is funny that fat characters are dancing. Of course it is, right? Except for the problematic message this sends. And the fact that ballet is rife with eating disordered young dancers. I’m reminded of the documentary series Big Ballet which sets out to defy expectations by employing dancers with bigger bodies.

For the Channel 4 documentary series Big Ballet, 18 amateur plus-sized dancers were selected from 500 applicants for an experiment: under instruction from former Royal Ballet principal Wayne Sleep and dancer turned artistic director Monica Loughman, the larger ladies (and a couple of men) had just 20 weekends to master Swan Lake.

The Independent

I wonder if Prawn Lake could have been just as funny? I really don’t know. And if we lived in a culture where there was no body-size shaming, this book stands up just fine. I’m simply pointing this out type of humour as an example of just how deeply fat politics run.