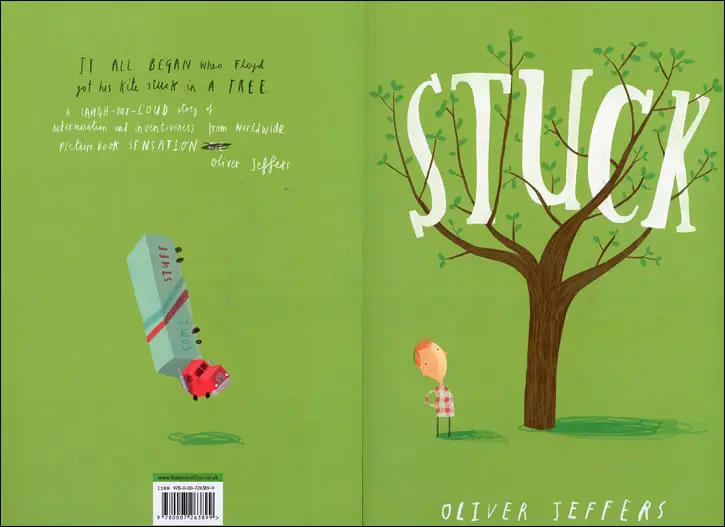

When Floyd’s kite gets stuck in a tree, he tries to knock it down with increasingly larger and more outrageous things. A perfect picture book by Oliver Jeffers.

STORY STRUCTURE OF STUCK

There’s a long oral tradition of stories which get cumulatively more and more ridiculous until the most ridiculous idea ends the story. “The Three Lazy Sons” is from one of the earlier Grimm collections and demonstrates the tradition nicely. In this fairytale, a king is trying to choose which of his three sons will be king after his death. For some reason that only makes sense according to fairytale logic, the king decides that his laziest son shall be king. The sons plead their case:

- The kingdom belongs to me, for I’m so lazy that when I’m lying on my back and want to sleep and a drop of rain falls on my eyes, I won’t even shut them so I can fall asleep.

- I’m so lazy that when I’m sitting by the fire to warm myself, I’d sooner let my heels be burned than draw back my feet.

- I’m so lazy that if I were about to be hanged and the noose were already around my neck and someone handed me a sharp knife to cut the rope, I’d rather let myself be hanged than lift my hand to cut the rope.

This reminds of the Yo Mama category of boasting, in which (mostly) young men compete to come up with the most ridiculous insults about someone else’s mother. These, too, are an oral tradition. Picture books, meant to be read aloud, borrow heavily from the oral tradition.

This is a subcategory of cumulative tale in which a character has a problem and tries to fix it by accumulating more problems, only making the matter worse.

The ur-story of this kind might be There Was An Old Lady Who Swallowed A Fly. There’s also the folktale about the man whose house is too noisy, so he is advised to fill it up with other noises in order to distract from the previous one. A 1967 picture book example of this story is Too Much Noise by Anne McGovern, illustrated by Simms Taback. Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler revived the story a few decades later and called it A Squash and a Squeeze. Clearly, this gag is still going strong. You see it as a gag in other stories, for instance in Michael Bond’s Paddington Bear scene in which Paddington is making a table but can’t get the legs even so he tries to fix the problem by cutting the legs shorter and shorter.

SHORTCOMING

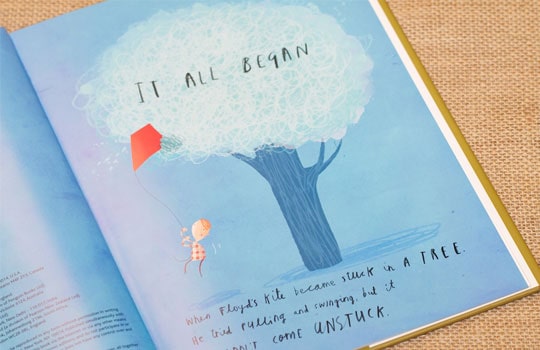

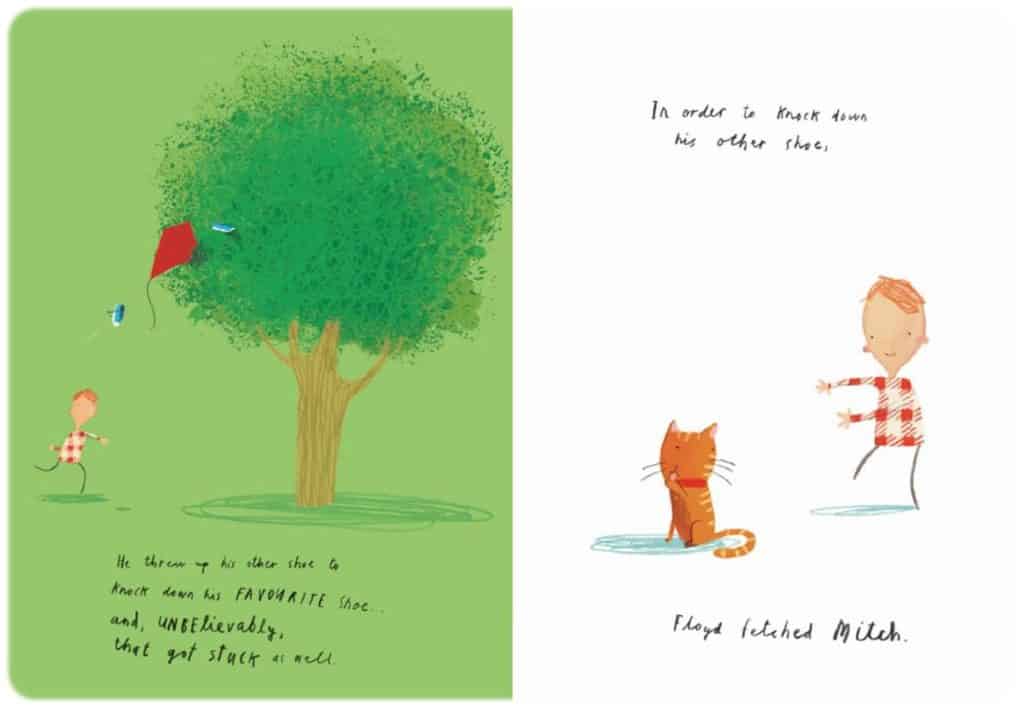

Floyd is not exactly a pro with the kite. It has got stuck in a tree.

Floyd is not sensible.

Notice how the phrase “It all began…” puts us in mind of some great event from the past, something legendary and unforgettable.

CHARACTER NAME FLOYD

According to the Internet:

The name Floyd is a Welsh baby name. In Welsh the meaning of the name Floyd is

- Grey.

- One with grey hair.

In common use as both a surname and first name.

I often look up children’s book character names in case they are somehow meaningful. I don’t think this one is. Little Floyd has bright red hair. (I am sure kids with red hair are way more common in books than in real life!)

DESIRE

He wants to remove the kite from the tree so he can have more fun.

OPPONENT

The tree.

PLAN

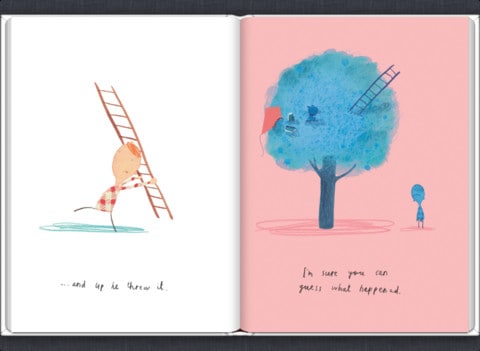

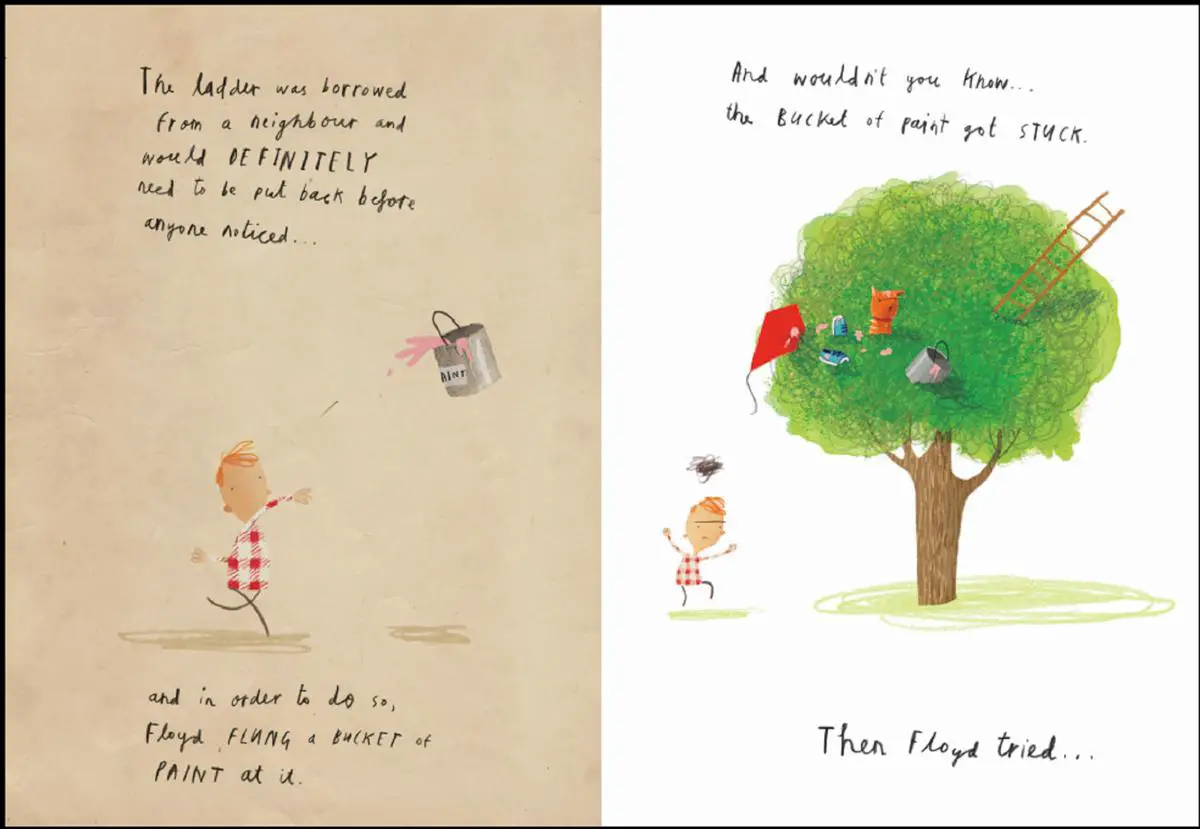

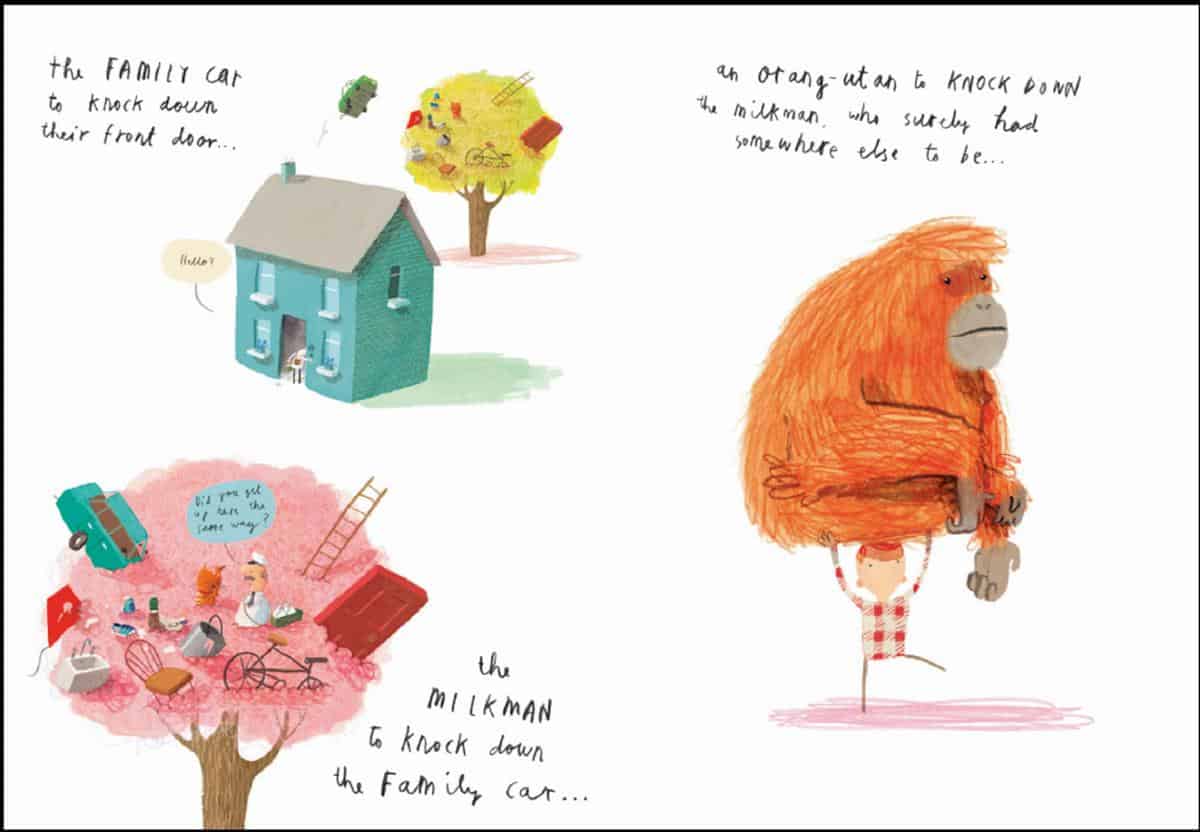

The plan stage of this book comprises the bulk of the story and is a great source of humour, because everything Floyd throws into the tree gets stuck. His ideas for retrieval get more and more ridiculous. In common with many comedic characters, Floyd’s behaviour is funny because he just won’t learn. The young reader learns, though, and there is great dramatic irony when we see what he’s about to do, then he does it and… SURE ENOUGH! It doesn’t work.

BIG STRUGGLE

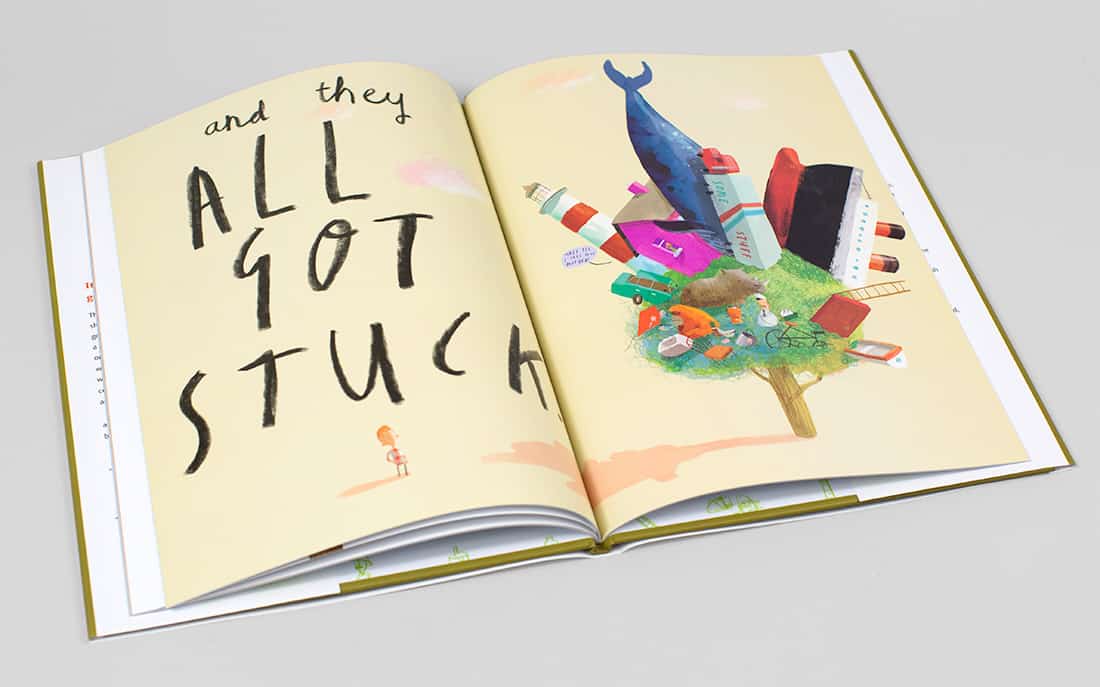

There’s a particular kind of deus ex machina that is fine to use in humorous picture books (we also see this in Walter The Farting Dog) — a police car or a fire brigade just happens to be passing. The fact that they just happen to be passing at the exact right time is funny in its own right. In general, though, it pays not to have adults in authority stepping in to save the day, and here Jeffers subverts that by showing Floyd with the fireman in his arms as if he’s about to heave the fireman into the tree. (And by now we all know how that will turn out…) Turn the page and sure enough, Floyd has got the firemen AND the truck stuck in the tree.

ANAGNORISIS

In picture books, sometimes the anagnorisis is signposted with a lightbulb above the head. (Oliver Jeffers likes lightbulbs.)

Then he had an idea, and went to find a saw.

But masterfully, even the anagnorisis phase of the story is subverted by this master storyteller. The trick works — the saw indeed gets the kite down — but not in the way we expect.

NEW SITUATION

That night Floyd fell asleep exhausted. Though before he did, he could have sworn there was something he was forgetting.

Through the window, we see everything, including the firemen, are still stuck in the tree.

This picture book is a ‘never-ending story’, because we already know that the firemen are going to go through their own, similar rigmarole trying to get themselves dislodged.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

There doesn’t seem to be a reason why the character is named Floyd, but can there be a reason why Floyd’s hair is red, however? Or a reason why the kite is red? The kite is important to Floyd and they are linked by the colour red. When the kite gets stuck in the tree, to Floyd the situation is as dire as if he himself were stuck, irretrievably, in the tree.

I feel that Oliver Jeffers’ picture books, even more than other picture books, have been made to be shared with an adult co-reader.

The big clue? Jeffers’ handwriting is pretty hard to read. In fact, my eight-year-old has trouble reading it. The ability to read individuals’ handwriting comes quite a long time after learning how to read common typefaces and their teacher’s perfect, slanting script. This book is similar to The Day The Crayons Quit, in that regard. (I like this book a lot less than I like this one.)

MOVEMENT FROM LEFT TO RIGHT

In Western picture books, the default movement through a story is from left to right, as the page turns. But illustrators can deliberately invert this convention, causing some sort of obstacle to the progression of story, by depicting the main character facing left, unable to move forward. We see this here, too:

We see it again when ‘Floyd fetched a ladder,’ and on the following page as well, which is mainly blue (symbolic of Floyd’s general mood). In short, Jeffers has used this trick three time, making use of the rule of three.

Another interesting trick Jeffers uses is to do with colour. Often in a story like this, when an action is established and supposed to continue on and on, long after it has become interesting, you’ll find a double spread in which the actions are compressed into a series of thumbnail actions.

Here, too, we have the double spread which starts with ‘a duck to knock down the bucket of paint…’ Notice Jeffers has switched to a single dominant hue for each half of the page — a greeny-yellow for the left, orange-sepia for the right. Why did he do this?

Picturebook art has been influenced by the age of photography, and this may be a recreation of a page of old-fashioned photographs you might find in an album — photos which have been taken on the day of some important event.

Or, it may simply be because the reader is not meant to linger on this page, enjoying the artwork. Jeffers knows that the child is keen to know the outcome — does Floyd get his kite back? The limited palette means these pictures don’t draw attention to themselves.

COLOUR TO SIGNIFY A TALL TALE

But that’s not the only thing Jeffers did with colour — the tree is a different colour in every picture. We understand that it’s the same tree. Why change its colour?

This is a subtle clue that the story is a tall one, not to be taken seriously. Of course the whole thing is made up. It’s one of those stories that has been told over and over many times. Maybe, in Floyd’s (Oliver’s) youth, a kite did get stuck in a tree and maybe it required several shoes before it came down. Over the years, this story gets embellished and built upon until it reaches a ridiculous level. The tree itself changes colour to suit the mood of the storyteller.

The main requirement of a tall tale is exaggeration: There are unbelievable creatures, huge fish, large distances, huge volumes. But hyperbole alone does not mean ‘tallness’. In a tall tale, the listener must both accept and refute. The listener has to know enough of the environment in which the tale is told to realise this can’t be true. The line between fact and fiction is hazy, and the humour derives from pushing that boundary. Which parts of this story are true, and which aren’t?

STORY SPECIFICATIONS OF STUCK

Everything is about 400-500 words these days. This picture book is no exception, coming in at 493 words.

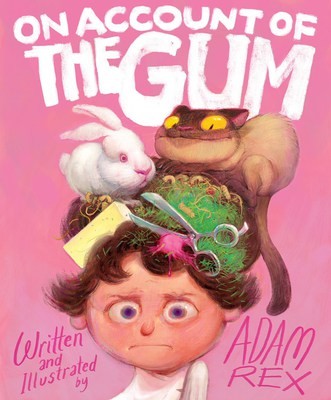

On Account of the Gum is a book about how the best intentions lead to some of the worst (and funniest) ideas!

Serious humor abounds in this story about one kid’s hilarious misadventures with gum, and the cumulative buildup of stuff stuck in hair.

How do you get gum out of your hair—a pair of scissors? Butter? The cat? Call your aunt, she’ll know what to do. She doesn’t? Try the fire department!

With each page turn, this situation—relatable to any family—grows stickier and more desperate.

FURTHER

Sometimes a real life ‘Stuck’ situation makes it onto someone’s phone, then onto Reddit.