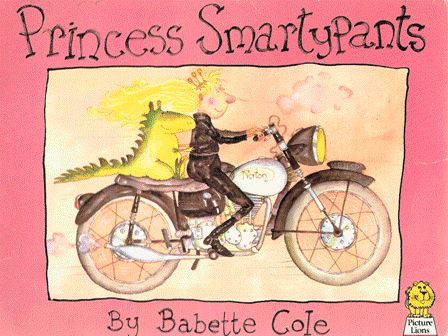

Princess Smartypants is an example of a children’s picture book which uses gender reversal to tell a story that would never really happen. What if women of high socio-economic status could choose their own marriage/non-marriage partners? The ending plays into the stereotypically MRA fear — if women were allowed autonomy they may choose not to include men at all.

Princess Smartypants has been talked about quite a bit by children’s literature critics, though I personally feel it’s not as successful as it looks at first glance. It’s still notably, however, as an early example of reversal as a way of highlighting inequality.

Gloria Steinem wrote in her 1994 book Moving Beyond Words that she has ‘gained a lot of faith in reversals’ as a way of highlighting structural inequalities and prejudices:

[Reversals] create empathy and are great detectors of bias, in ourselves as well as in others, for they expose injustices that seem normal and so are invisible. In fact, the deeper and less visible the bias, the more helpful it is to take some commonly accepted notion about one race, class, ethnicity, ability — whatever — and see how it sounds when transferred to another. […] To uncover the difference between what is and what could be, we may need the “Aha!” that comes from exchanging subject for object, the flash of recognition that starts with the smile, the moment of changed viewpoint that turns the world upside down.

Steinem then goes on to make a great job of turning Sigmund Freud into Phyllis Freud, with all of the misogynistic and historically dangerous ideas reversed, in a world where women hold the power instead of men; where the uterus is revered rather than the phallus.

STORY STRUCTURE OF PRINCESS SMARTYPANTS

Types of Archetypal Journeys

Heroes in stories will set out to accomplish one of the following 10 things. Here, of course, we have a story about number five:

1. The quest for identity

2. The epic journey to find the promised land/to found the good city

3. The quest for vengeance

4. The warrior’s journey to save his people

5. The search for love (to rescue the princess/damsel in distress)

6. The journey in search of knowledge

7. The tragic quest: penance or self-denial

8. The fool’s errand

9. The quest to rid the land of danger

10. The grail quest (the quest for human perfection)

Babette Cole subverts the reader’s expectation that the prince and princess will end up married. These days it doesn’t seem such a radical story at all, but that’s only because we’ve seen it before.

I feel this story is very much an ancestor of the Pixar film Brave:

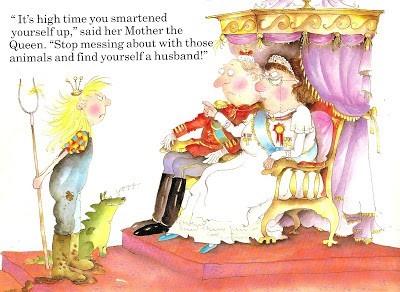

- A princess whose parents tell her its time to put away childish, tomboy things and get married

- The princess doesn’t exactly fit the princess ideal — Merida because of her wild, red hair and Smartypants because of her large, red nose.

- A succession of tests for potential suitors

- In which the suitors make bumbling fools of themselves by slapstick means.

I’m no huge fan of Brave. I do know a few little girls who love it to bits, mainly because of the archery. But there’s something not quite right about the story arc, and I feel it’s a bit cheap to play the princes for laughs.

As expressed eloquently by Circadian Rhythms:

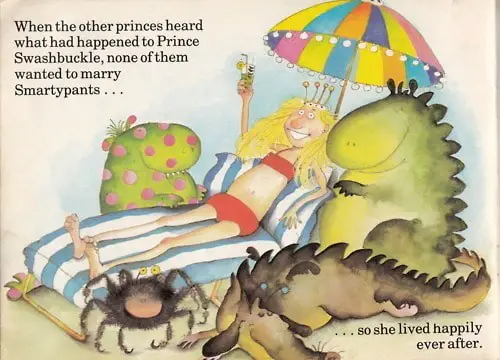

This [narrative] isn’t just saying that women don’t have to marry, it’s saying that women can humiliate men, force them to work, then don’t marry them. In fact, Princess Smartypants can only live happily ever after when she has rid herself of essentially all men (who are, needless to say, intimidated by her transfiguring osculations). Just like all women! We females can only be free once men have become the toads they are at heart!

Not only that, but the scene in which the prince is made to go shopping with the Queen mother shows him humiliated, not just because of his crawling position, but because he is in the lingerie department, weighed down by a load of female undergarments. It’s impossible to view this scene as humbling without also acknowledging at some level that female undergarments are inherently funny and shameful.

However, back in the mid 1980s when Princess Smartypants was published, the world was seeing feminist inversions of classic tales for the first time.

SETTING OF PRINCESS SMARTYPANTS

This is a parody of fairytales in general and borrows parts from all the famous ones.

- The castle is in ‘fairytale land’, but in a modern (1980s) twist

- The story makes use of the rule of threes, with three bumbling suitors

- Thrones, crowns, moats, a forest, horses and castles

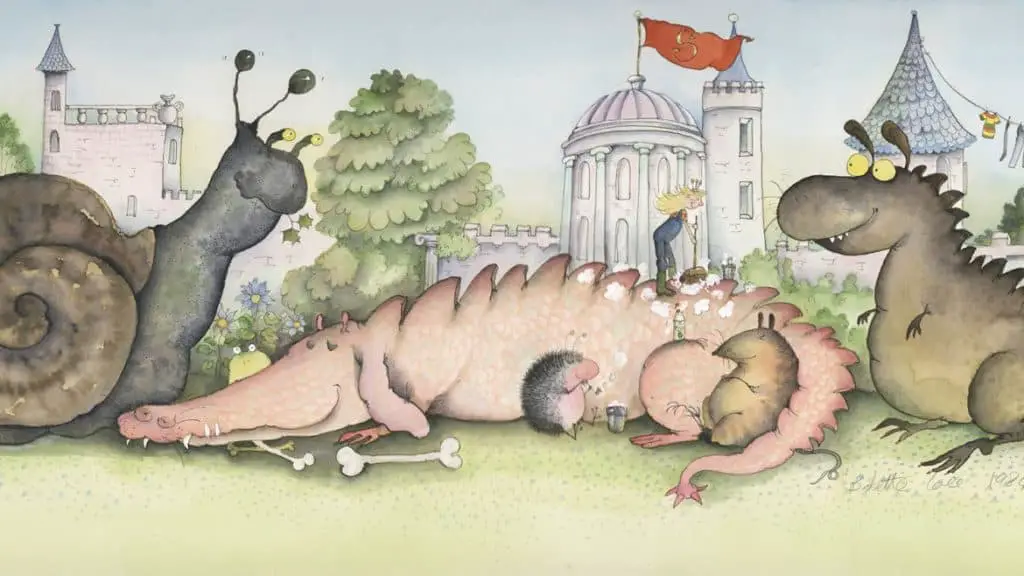

- (Comically) scary mythical creatures

- A high tower made of glass (Rapunzel/Cinderella?)

- A magic ring

- Thrown into a pond (The Frog Prince etc)

SHORTCOMING

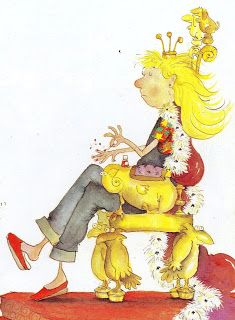

Princess Smartypants has been born into a life with a rigid path; she must marry into royalty (and produce heirs).

DESIRE

However, she doesn’t want that life. She wants to remain single and buck conventional gender roles.

OPPONENT

The parents, who represent the entire culture of marital expectations

PLAN

She’ll vet some suitors, but she’ll set such enormous tasks that there’s no way they’ll be able to accomplish them.

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle scenes comprise a large proportion of a picturebook, and sure enough the princes are put through a series of tasks which involve her scary pets or scary rides.

But ultimately, Princes Swashbuckle is able to accomplish all of these tasks. Princess Smartypants has lost the big struggle.

ANAGNORISIS

Except Prince Swashbuckle is not interested in her.

A ‘swashbuckler’ is an idealistic hero archetype. He rescues damsels in distress, defends the downtrodden, and in general saves the day.

However, to a modern audience the swashbuckler hero feels like a parody of himself. He is often a little bit camp. This much is left unsaid; instead, Princess Smartypants is required to kiss him (following her own rules of the game) but he turns into a frog, in an inversion of the Princess And The Frog fairytale.

NEW SITUATION