Pig the Pug and Trevor the sausage dog live together in a flat. Pig is greedy and selfish and refuses to share his toys. Trevor suggests they play together, but Pig refuses. He piles up all his toys and sits on top of them, but the pile collapses. Pig ends up covered in bandages, completely unable to escape Trevor’s attentions. For now, Trevor is allowed to share.

WONDERFULNESS OF PIG THE PUG

In Pig the Pug, the character’s moral and psychological needs are spelt-out for the young reader on the very first page:

Pig was a Pug

and I’m sorry to say,

he was greedy and selfish

in most every way.

Pug’s psychological need is that he’s scared that if he shares his toys he’ll lose control of them. Pug’s moral need is that he needs to start treating other dogs better, and learn to share his toys.

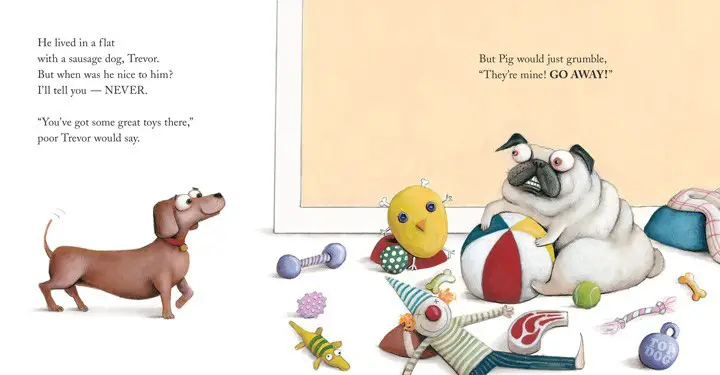

Main characters also need an obvious desire. Pig desires to keep all of his toys to himself.

But Pig would just grumble,

‘They’re mine! GO AWAY!’

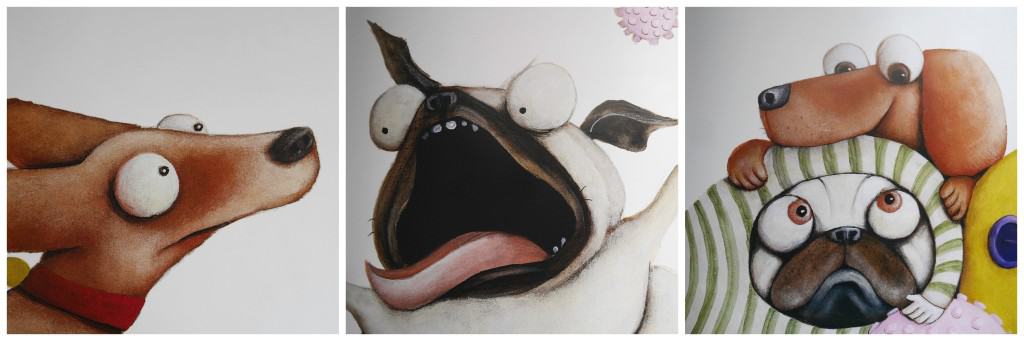

The main character and the opponent must find themselves thrown together. In real life, people who don’t like each other tend to avoid each other, so storytellers must contrive naturalistic scenes in which opponents have to somehow work out their differences. Here we have the naturalistic environment of two dogs pushed together by dog-owners oblivious to the machinations of dog-friendship. Blabey makes the most of this discomfort in the illustrations, and the following facial expressions (from the subsequent book, Pig the Fibber) say it all:

A note on Pig’s scope of change: Usually in picture books (and indeed in film for adults), main characters have some sort of epiphany and realise they’d better start treating others better. The transgressive thing about this story is that Pig has not necessarily changed at all. He may be just as selfish as he ever was, but wrapped up in bandages, there’s nothing he can do about Trevor using his toys. The character arc has happened in Trevor, who has realised that Pig needn’t always be the top dog (quite literally) around here. Pig’s lack of character change is all the more comical because the previous two double spreads lead us to think that this is your average moralistic story about a dog who learned to share:

These days it’s different,

I’m happy to say:

It’s so very different

in most every way

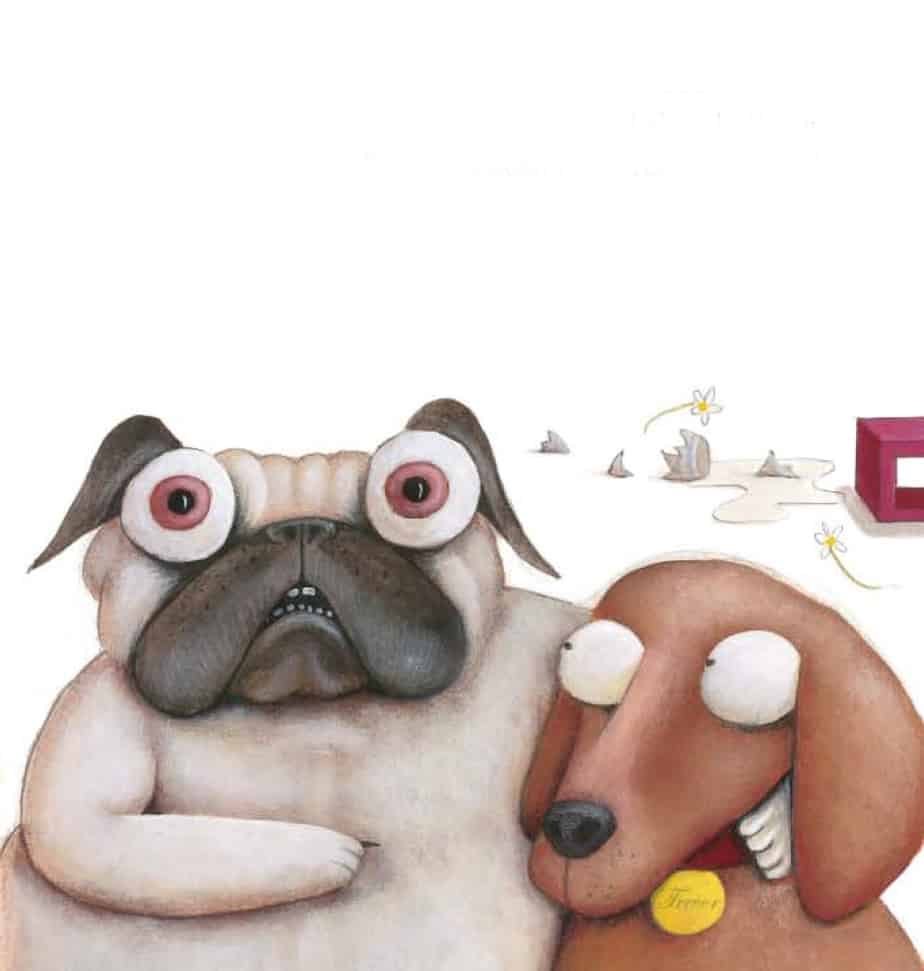

Next we see wonderful use of the close up, on Pig and Trevor’s faces. The close up is necessary because we need a bit of a build up — to be given the wider context so quickly would ruin the surprise ending. Notice that on the penultimate spread, Pug’s bandages are shielded by the arm of the clown toy, who has sort of come to life as a character in its own right…Turn the page and we see what has really happened.

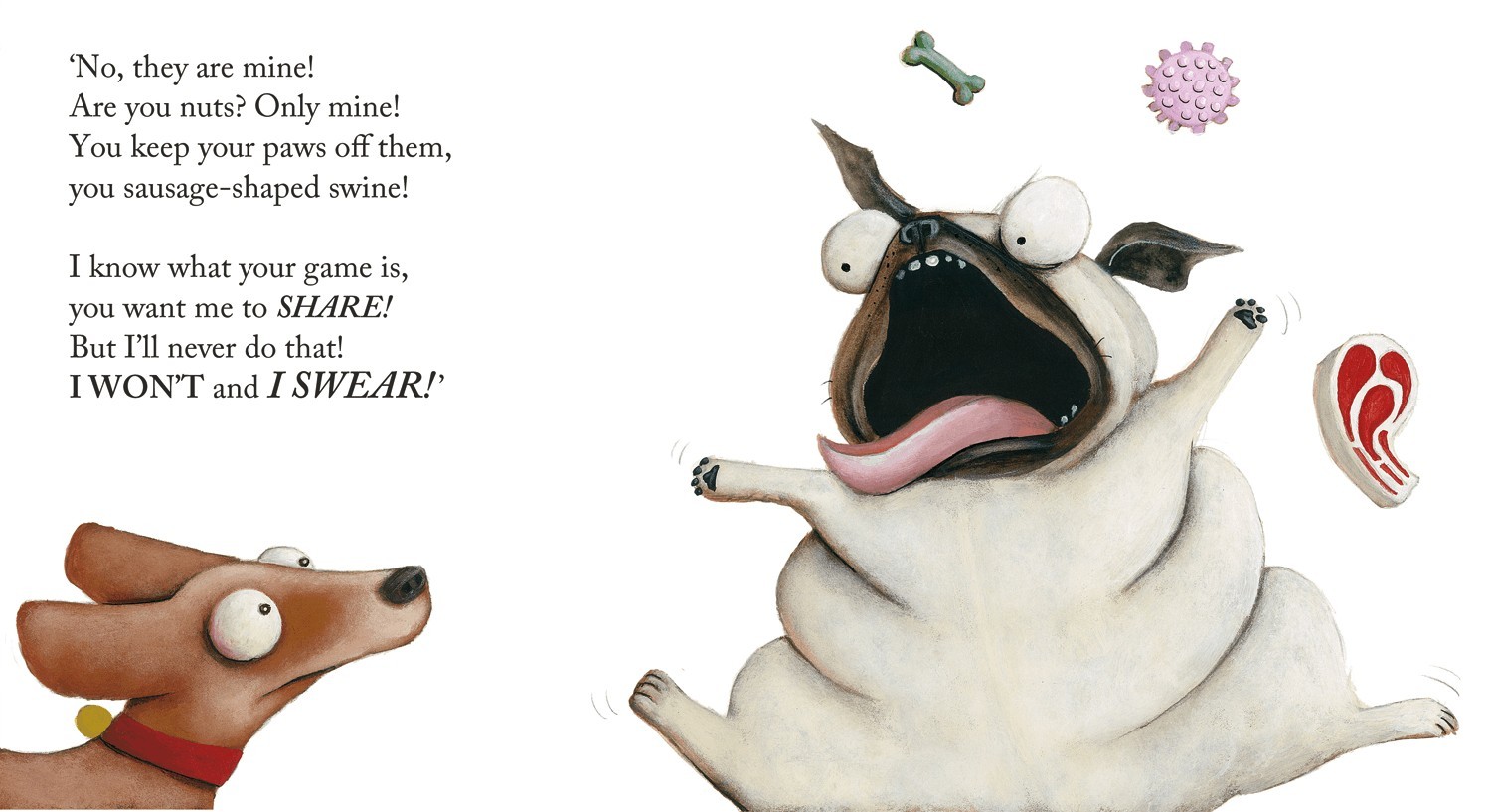

The main character in a good story is not self-aware of his moral need, otherwise you have no story at all. When Pig tells Trevor he is ‘a sausage-shaped swine’, this demonstrates the ultimate lack of self-awareness; after all, Pig has been named after a swine. He thereby projects his own failings onto his opponent, making the insult even more comical.

The interesting thing about Trevor (apart from his hilariously Australian name) is that he seems to know that he’s the goody-two-shoes of this story. Take a look at the following facial expression:

Is that a self-satisfied grin if ever you saw one? My daughter definitely feels sorry for Trevor, and was even a little upset when I laughed, but this grin is definitely for the adult co-readers if not for the children themselves — Trevor knows full-well that he is the Designated Good Dog. This allows us to empathise with Pig a little, too, and results in a story that isn’t black-hat, white-hat. The morality in this picture book for young readers is just a little more complex than that, should the reader be old enough to recognise it.

The use of idiomatic expression in this book is particularly appealing. I’m not sure how particularly Australian it is, but phrases such as, ‘Well, Pig flipped his wig’ add to the humour.

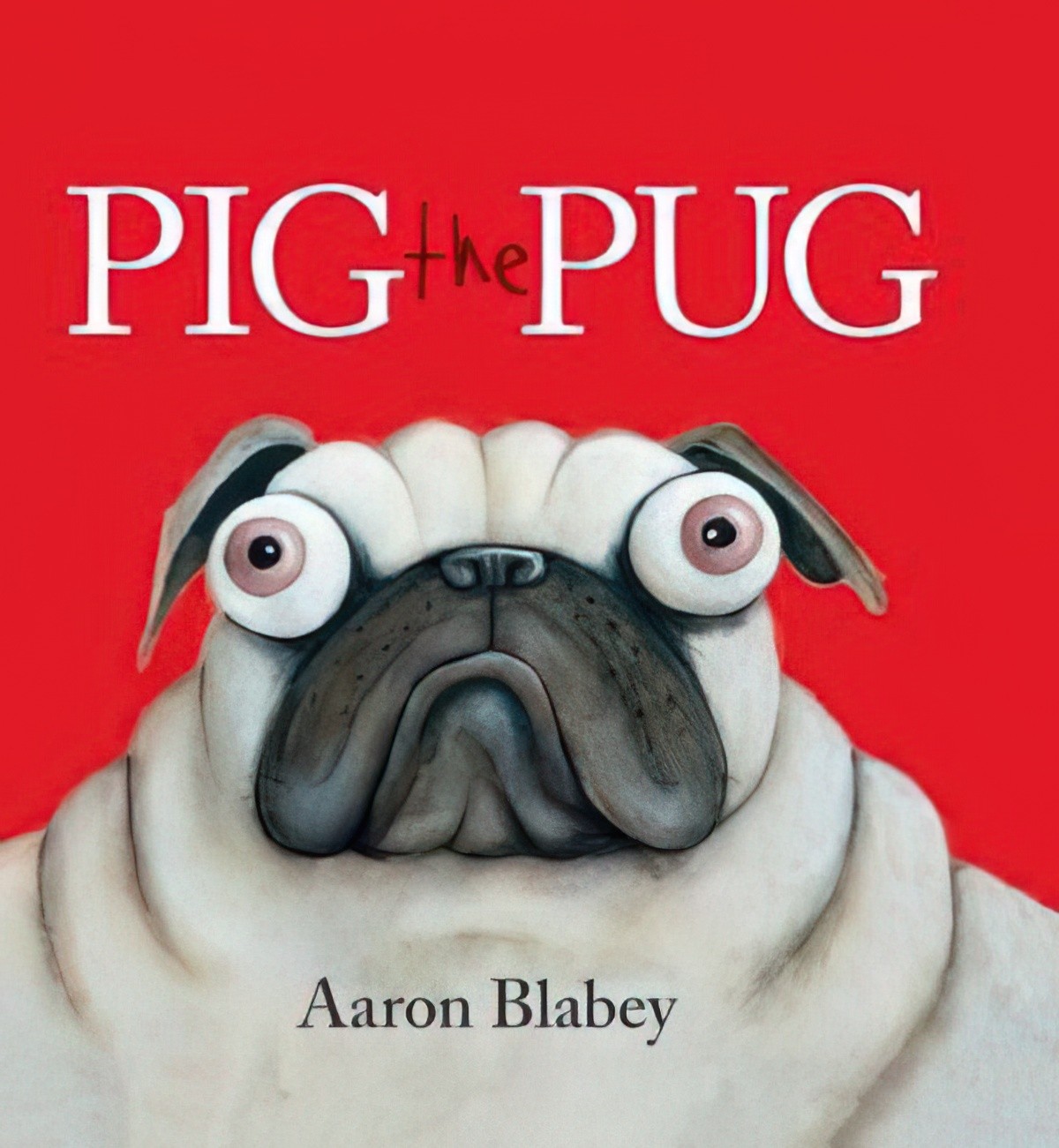

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

The first unusual thing about this picture book is the close-up of the main character on the cover. Very few picture books feature a close up — it’s far more likely to be a smiling medium- to long-shot. (Another exception in picture book world is the excellent retelling of Snow White, illustrated by Ekholm Burkert. Perhaps this is because pug dogs are inherently funny — at least if we ignore the ethics behind the over-breeding of dogs, which is a topic for a different blog. However, the fact that we have a close-up on Pug’s face AND the fact that Pug is not smiling, as is usual for characters on the front of picture books, tells us that we are to expect something just a little transgressive within.

There is humour in the intratext: Pig’s dish says ‘Mine’ rather than his name (more expected), and says to the reader that Pig’s owners know exactly what he’s like. Someone has given Pig a toy which says ‘Top Dog’, indicating that Pig is a spoiled brat, and probably came into the family before the more laid-back Trevor did.

This is a picturebook illustrated in modern style, with much use of negative space. The main action happens inside a house, and all the reader needs to know is that this is ‘inside a house’. There are no distinguishing features about the house at all — our attention is drawn only to the two dogs and the toys which are essential to the plot. Even when we see Pig piled high up on top of his toys in front of a window, the only clues we are given about there being a window is a view of the tops of pine trees and a couple of ‘m’ shapes in the sky to indicate birds. We therefore know that he is ‘high’.

One of Pig’s toys is a creature with googly eyes, much like Pig’s eyes. I’m not sure if it’s meant to be a crocodile or a sausage dog. If it’s meant to be a sausage dog, I love that it reinforces the ‘shadow in the hero’ idea.

Interestingly, Pig falls out the window rather than simply falling to the floor in a sorry heap. This allows for a different colour scheme of dark bricks rather than pale interior decor, and signals with colour the climax in the story.

But as mentioned above, the stand-out feature of these illustrations are the wonderfully expressive faces, which tell a good chunk of the story in their own right.

STORY SPECS

I’ve seen actors put out some very average books, but Pig The Pug is proof positive — alongside Julieanne Moore’s Freckleface Strawberry — that not all picture books written by actors are published due to platform alone. This is a genuinely wonderful rhyming picture book, and my seven-year-old daughter loves it. Her class has been working its way through all of Aaron Blabey’s books and she has asked me to buy them for her. I would happily do this, but it looks like Pig the Fibber is out of stock, I hope due to popular demand. I hope there’s going to be a reprinting/paperback version soon… I live in fear, because excellent Australian picturebooks quite often fall out of print, or never make it to softback. However, I predict this series will become classics. If you have to choose between Pig the Pug and Pig the Fibber, I’d go with Pig the Pug. Pig the Fibber uses the exact same structure and gag, with the inclusion of a cheap but effective farting episode, which never fails to amuse the seven-year-old set. UPDATE: There’s now an entire series of these books.

Published July 1st 2014 by Scholastic

24 pages

Shortlisted for 2015 CBCA Picture Book of the Year

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

This story reminds me of a subplot in the comedy Office Space, in which the character of Tom Smykowski is ironically overjoyed at having been severely disabled in a car accident which just happens to result in a big insurance payout as he is about to be laid off from work.

This, of course, is what makes Pig the Pug a little transgressive — the reader is encouraged to laugh at a creature covered in bandages. The humour wouldn’t work nearly so well if the character had lesser injuries of the type anyone might sustain—it’s the hyperbolic head-to-toe nature of the bandages which make these scenes funny.

I’m also reminded of the relationship between Garfield and Odie.

WRITE YOUR OWN

House pets make good opponents because they are stuck with each other. Are there any other situations in which animals/creatures/monsters are thrust in together? Lynley Dodd and several other picture book writers have picked the waiting room of a veterinary clinic as a stage for much slapstick drama. What if the pets run away? What if one animal is an established pet while the other is an intruder, like Tom and Jerry? There are many possibilities.

What is the psychological need AND the moral need of your main character? What does the main character desire most? Do they get it?

How might this story end just a little differently from all the other picture books of similar storyline that have come before? Blabey uses a very clever bit of slapstick at the climax, and unlike other picture books, Pig doesn’t learn his lesson.

Consider changing the colour scheme entirely at the battle scene (a.k.a. climax).