Olivia and the Missing Toy by Ian Falconer shows Olivia the Pig at her most bratty, and her parents at their most indulgent.

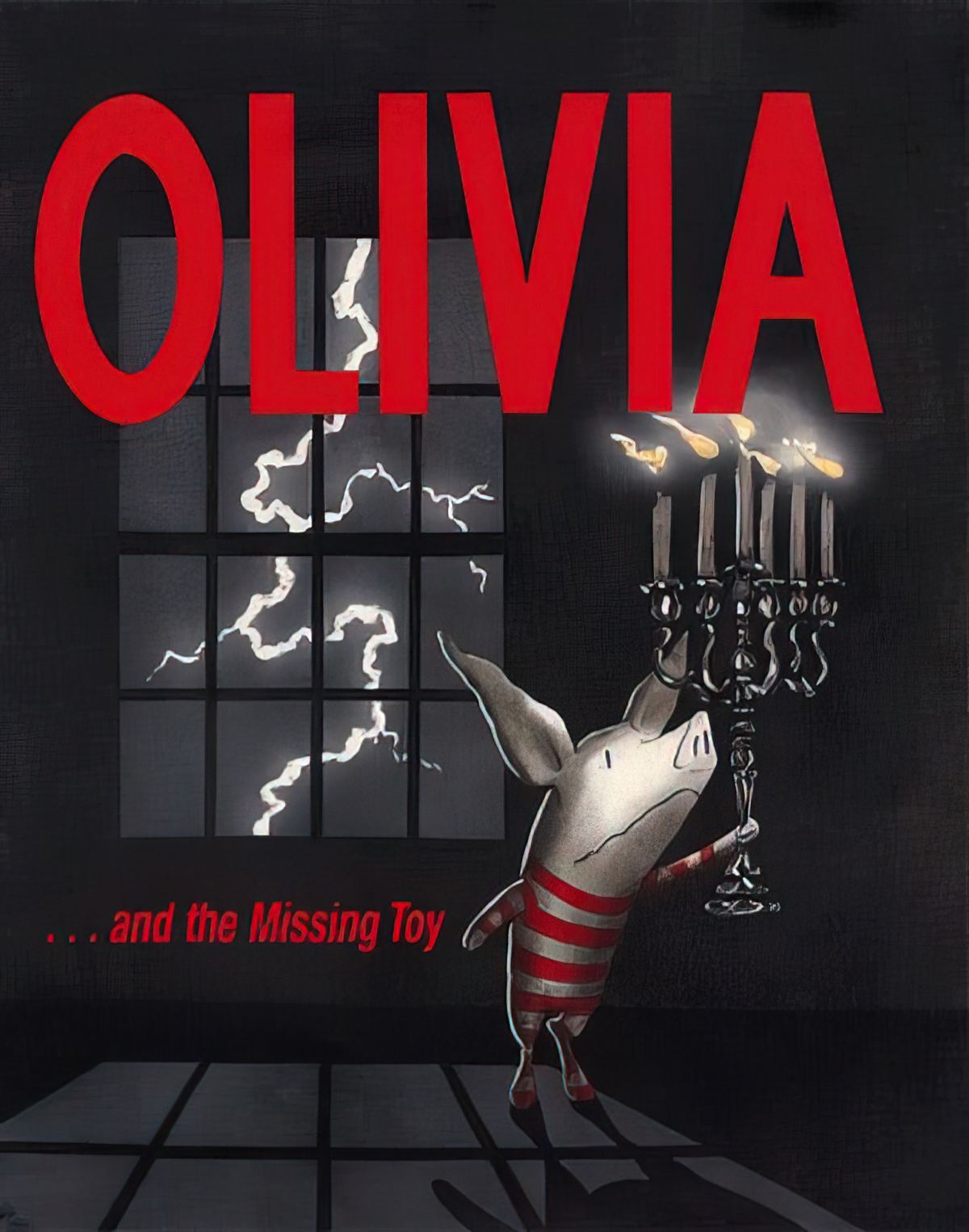

There are several versions of the book cover of Olivia and the Missing Toy, and the dark one is the scarier of the two.

The other is mostly white space, in keeping with most of the Olivia series. This book has a gothic episode in it — a definite spoof, with knowing use of the cliche “dark and stormy night”. Below, Margaret Blount explains one reason Olivia is a pig and not a little girl:

Even more suburbanised is Russell Hoban’s Frances where the child/animal substitution is so complete as to be unnoticeable. Frances the Badger is a small girl afraid of the dark, tucked up in bed but constantly annoying her parents by coming downstairs and interrupting the television. Why make her into an animal at all? The cosy delights of the Badger household — so like a human one — do remove the situation one or two degrees away from discomfort; some children are afraid of the dark, do dislike being alone.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

As for Olivia the pig, love her or hate her. Olivia is one popular children’s book character who pisses a lot of parents off, judging by reviews I have read online. While I don’t have a problem with some of the Olivia stories, this particular one annoys the hell out of me. That tends to happen when an adult reader sees a parenting style in a picture book with which we disagree. Here we have a demanding brat, an acquiescent mother and a father who is quick to say ‘I’ll buy you a new one’ after Olivia’s own carelessness with a toy.

I don’t think this is one of Falconer’s best. And it doesn’t just apply to the indulgent parents and bratty child character; the story structure is also a little odd and I don’t think it works. Why not? Let’s take a closer look.

STORY STRUCTURE OF OLIVIA AND THE MISSING TOY

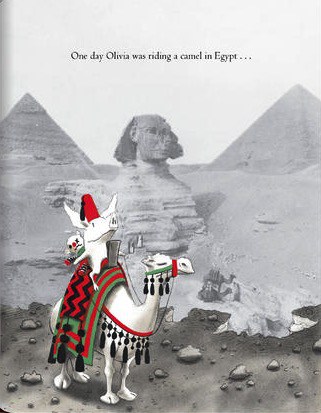

SHORTCOMING

The story actually opens with ‘One day Olivia was riding a camel in Europe…’ but unfortunately this is the most interesting part of the story and ends there. She wakes up and this was all a dream. I’m not sure how much Falconer has had to do with young children at the time he wrote this book, but I know very few Olivia’s age who need waking up by their parents. At this age they tend to leap out of bed earlier than everyone else in the house (unless their parents let them choose their own bedtimes, I suppose.) What is the reason for this opening? For one thing we do see the precious toy on the back of the camel. This shows how important the toy is to the character.

Shortcoming: Olivia is possibly too attached to a stuffed toy.

Next, Olivia does not like the colour of her soccer shirt.

She does not want to look like everyone else on her soccer team, even though the whole point of the uniform is to look like everyone else. (Explained by the mother.)

This particular shortcoming does not endear me to this character, as I feel it’s a self-absorbed and bratty kind of trait.

DESIRE

Olivia wants her mother to make her a red soccer shirt to replace the team green one. (The mother initially points out why this is a bad idea, then sets to work making the shirt anyway, on her sewing machine.)

This desire doesn’t work for me as a reader because soccer simply doesn’t work if everyone is wearing a random coloured shirt. The story should have been shut down right there.

OPPONENT

The opponent is introduced before we find out his exact mischief, and interestingly, we only see half of his little body at first. (The rest is off the page — as is the mischief.)

This is a nice technique.

An adult reader might be thinking Olivia’s true opponents are her over-indulgent parents. (They are making a monster.)

PLAN

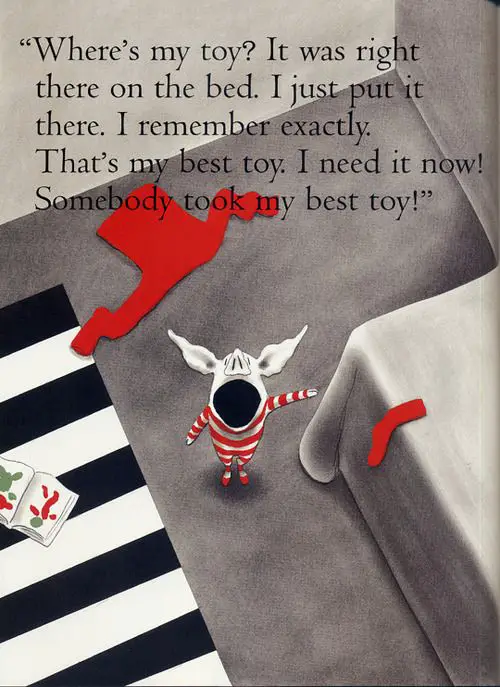

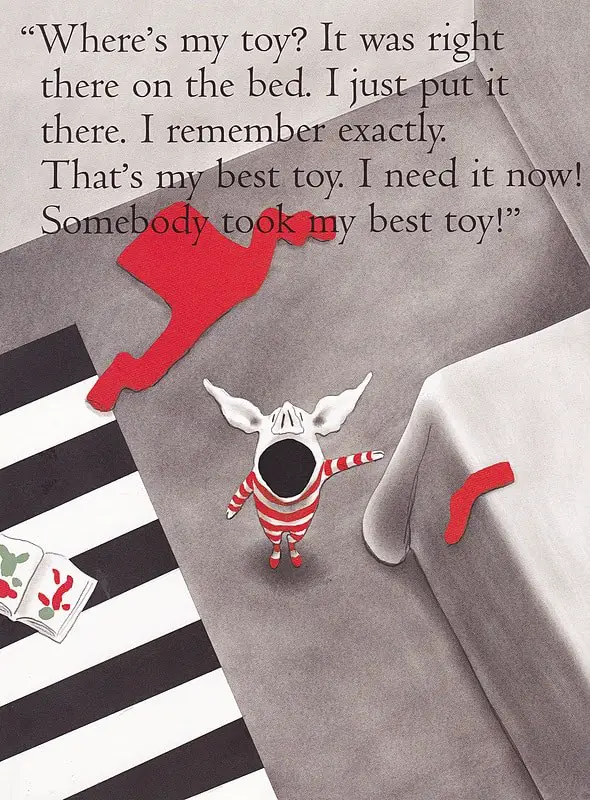

When Olivia realises her toy is missing she:

- Demands to know where it is by yelling at her mother.

- Yells even more loudly in her bedroom.

- Looks everywhere, including under the rug, under the sofa and under the (long-suffering) cat.

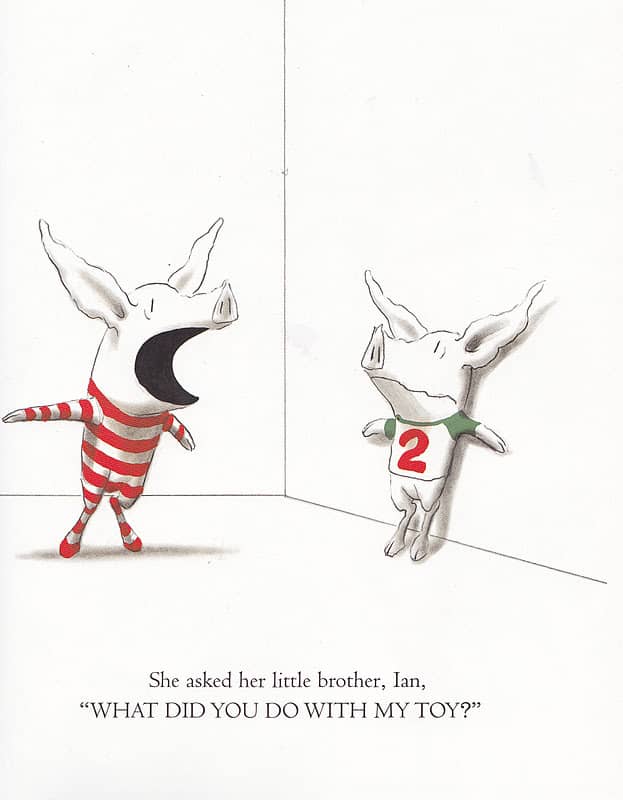

- Asks her little brother, and yells at him accusingly.

- Asks her baby brother, and yells at him even more loudly. (Volume is conveyed via capitalisation and font size.)

When none of these behaviours result in the location of the toy, Olivia gets up at night and plays the piano. (How this doesn’t wake the entire family, I’m not sure.) While giving up the hunt for the beloved toy is realistic given her young age, readers do love heroes who persevere. Olivia is neither a persevering nor a patient pig. (She is, however, petulant and possessive, riffing on the p’s.)

BIG STRUGGLE

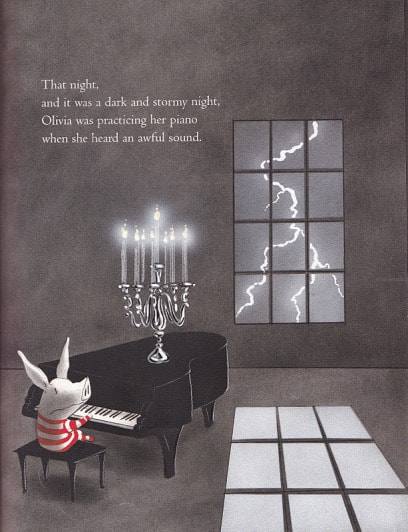

With the switch to the gothic genre, signified by the darkened rooms, the candelabra, the realistically depicted lightning bolt which illuminates the bars on the window, and finally by the scary noise, Olivia checks out the sound coming from behind the door.

ANAGNORISIS

Olivia finds her toy, but there is no anagnorisis. She runs to her parents (it’s now the next morning, and yet again we have another stereotypical depiction of the father reading the newspaper while the mother cares for the youngest kid), and Olivia tattle-tales on the dog, expecting her parents to do something about the situation. The mother expresses her condolences. The father says, “Don’t worry, tomorrow we’ll go get you the best toy in the whole world.”

I really really want him to say, “Serves you right for leaving it lying around. Now go fix it.”

Fortunately, despite the indulgent parenting style of her parents, Olivia decides to fix the toy herself and shows great initiative by sewing it up herself. This is why I don’t mind Olivia; it’s her parents who shit me to tears. The other nice thing about Olivia as a character is that she is happy with her self-fixed toy even though it looks nothing like it did before. She doesn’t throw any tantrums about lacking the skills to fix it properly.

It’s interesting that Falconer didn’t want the words ‘All better” on this page, but the editor insisted upon it.

[Falconer] says he lost one argument: the addition of the words “All better” when Olivia repairs her missing and mangled toy. “A mommy phrase,” says the author. “Something kids would repeat,” says the editor.

USA Today

NEW SITUATION

Olivia holds a brief grudge against the dog and won’t let her mother read her any books about dogs for this one night.

And if you were wondering about what those books are (only partially depicted on the page):

She’s shown carrying four titles: The Cat in the Hat, Puss in Boots. Krazy Kat and Kitty Foyle.

Kitty Foyle? “A 1930s movie with Ginger Rogers,” Falconer says. “A little joke that no one will get.”

USA Today

“But even Olivia couldn’t stay mad forever”. She lets him sleep in her bed, along with the mended toy.

MCGUFFINS AS PLOT DEVICE: GOOD MCGUFFIN, BAD MCGUFFIN

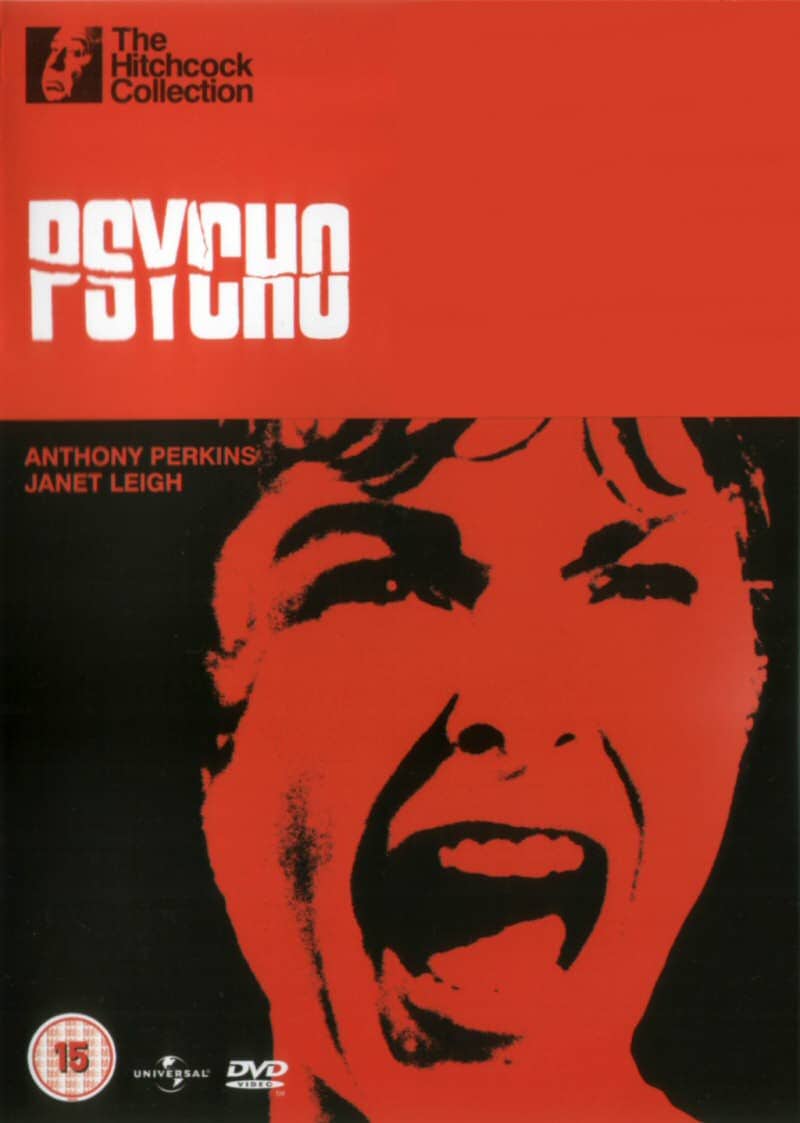

Here’s the problem with this plot: The whole sequence with the shirt is a Macguffin. A m(a)cguffin, sometimes called ‘a weenie’ is a plot device whose function is to get the action going, but which may be forgotten or become irrelevant by the end of the story. Others use the term simply to mean ‘anything that gets the plot rolling’. But technically, by Hitchcock’s definition — he invented it — a true McGuffin must be forgotten by the audience.

Sure enough, we’ve forgotten all about the shirt by the end of the story, as has Olivia.

A famous example of a McGuffin is in the film Psycho, in which Marion Crane steals money early in the film, which brings her to the Bates Hotel. By the end of the film, no one cares about what happened to the money.

Olivia and the Missing Toy is, of course, a spoof of a psychological drama such as Psycho. (The colour scheme of black, red and white lends the series really well to a spoof of something horrific.) So Falconer opened with a technique often used in that form. Here’s a question: Can the McGuffin work as well in a picture book? In a story of 42 pages, 11 (excluding the camel scene opener) are taken up by the whole shirt palaver. (On the eleventh page it is seen cast aside, as Olivia descends into her tantrum.) That’s a huge portion of the entire story.

The first question is: Why does the McGuffin work in Psycho?

- It gives Marion Crane a reason to skip town and removes the option of going back. (Plot reasons.)

- It gives the character of Marion Crane a moral shortcoming, which the audience needs in order to see the character as rounded. A moral shortcoming also makes a character more interesting.

- It gives the audience a satisfying frisson of ‘serves you right’ when Marion is scared out of her wits.

As for the McGuffin in Olivia and the Missing Toy:

- There is no real plot reason for this McGuffin.

- It gives the character of Olivia a moral shortcoming — she treats her family badly when she loses something, BUT…

- There is no satisfaction for the audience here, because Olivia is a brat without a cause. There is no anagnorisis, there are no consequences.

In sum, this particular book in the Olivia series doesn’t really work as a story.