Olivia and the Fairy Princesses is the third Olivia book I’m taking a close look at; the first was Olivia, which I really liked; the next was Olivia and the Missing Toy which I really didn’t and now for a story which has garnered Olivia a bit of a reputation among reviewers on social media for being a great feminist read.

The ideology in Olivia and the Fairy Princesses is clear: Little girls don’t need to ALL dress up as pretty pink fairytale princesses if they don’t want to . They don’t even have to be pretty. And if they do want to dress up as a princess, there are plenty of options from other cultures from which to choose.

I live in the Village in New York City, and it has become radically gentrified in the last 15 years. All of these little girls walk around with their wands and their tutus. There are squads of them roving the streets. And Olivia would want none of that.

The story came out of working with my sister, who is also my assistant, and doing the marketing. We oversee as best we can the kind of toys they produce. We kept running into this problem – they all wanted to do pink, pink, pink. I had to say, “No, no, everybody’s doing pink! How many pink tutus can you sell?” Marketing people just want to stick to something safe, I guess.

Falconer also says he was directly influenced by this video which went viral a few years back, which shows you the power cute YouTube rants can have on pop culture!

Anyone with a passing interest in issues such as those discussed in Cinderella Ate My Daughter or Packaging Girlhood will be happy to see a message like this.

Pink and pretty or predatory and hardened, sexualized girlhood influences our daughters from infancy onward, telling them that how a girl looks matters more than who she is. Somewhere between the exhilarating rise of Girl Power in the 1990s and today, the pursuit of physical perfection has been recast as a source—the source—of female empowerment. And commercialization has spread the message faster and farther, reaching girls at ever-younger ages.

But, realistically, how many times can you say no when your daughter begs for a pint-size wedding gown or the latest Hannah Montana CD? And how dangerous is pink and pretty anyway—especially given girls’ successes in the classroom and on the playing field? Being a princess is just make-believe, after all; eventually they grow out of it. Or do they? Does playing Cinderella shield girls from early sexualization—or prime them for it? Could today’s little princess become tomorrow’s sexting teen? And what if she does? Would that make her in charge of her sexuality—or an unwitting captive to it?

A cautionary account of how culture, media, and marketers influence how girls dress as well as their developing senses of identity and esteem counsels parents on how to talk to their daughters in order to help them build resilience against negative stereotypes and messages.

I count Olivia and the Fairy Princesses as an example of a children’s book which unjustly basks in the glory of seeming feminist only because, after a few centuries of symbolic annihilation, the bar is set so very low.

STORY STRUCTURE OF OLIVIA AND THE FAIRY PRINCESSES

SHORTCOMING

Olivia was depressed.

“I think I’m having an identity crisis,” she told her parents. “I don’t know what I should be!”

DESIRE

Olivia wants to be different. This is Olivia’s enduring desire right throughout the series.

“Well,” said her father, “you’ll always be my little princess!”

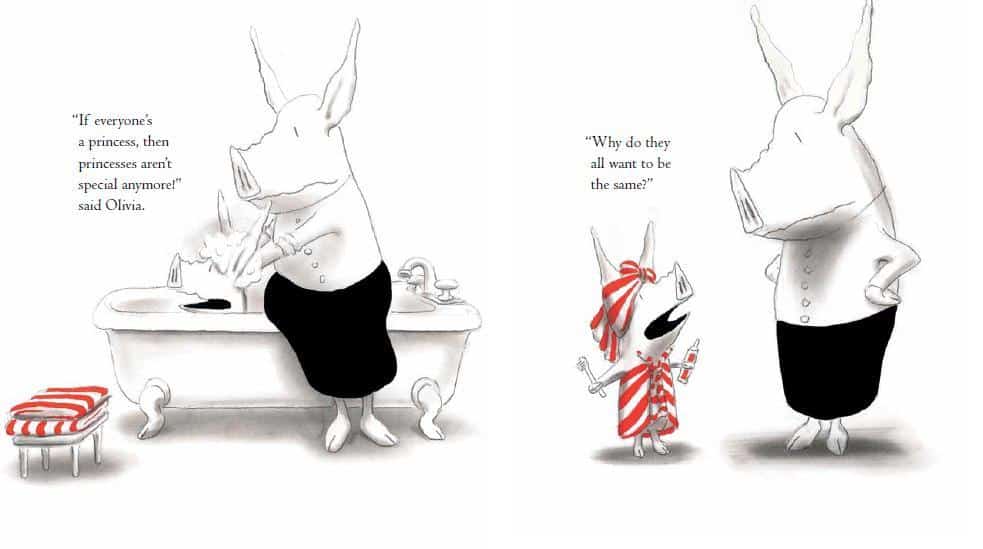

“That’s the problem,” said Olivia. “All the girls want to be princesses.”

This is why I love Olivia but can’t stand her parents.

OPPONENT

“There are no mean girls in this book. There’s no rival here,” Falconer says in the PW interview, pinpointing a common problem in books about groups of girls — authors and screenwriters are inclined to oversimplify the complexity of girlhood hierarchies. Few authors have a really nuanced grip on what girl cliques really feel like when you’re in them. Falconer side-steps the problem here, wisely, I think.

So who is the opponent? The opponent is ‘The Dominant Culture’ — the Unwritten Rule Of Girls Must Be Pretty & Pink.

With a picture book, your main age range is from about 3 years old to 6, which is just before all that Queen Bee stuff starts to kick in.

But take a look at chapter books and middle grade novels and you’ll start to find a lot more Mean Girl opponents — they’re usually blonde and pretty, even if the prettiness simply equals nice clothes, shiny accoutrements and ringlets. We see it all the way from Ramona to Junie B. Jones. There’s even the ‘blonde equals prettier’ thing going on with the Ingalls sisters.

PLAN

Olivia plans to snub convention and dress up in a variety of different costumes.

BIG STRUGGLE

The closest we have to a real, setting big struggle scene is when Olivia enters the party dressed as the warthog and obviously scares the pretty little girls.

But there are other mini big struggle scenes played out in the books read to Olivia by her mother that night.

ANAGNORISIS

Then it occured to her. “I know…”

“I want to be queen.”

NEW SITUATION

The new situation portion of this story is absent, probably because this is a series and we know we’ll hear from Olivia again. We can safely assume that she’ll continue to behave as narcissistic queen of the world in the next book, too!

So, is this book feminist?

IN THE YES COLUMN

- Olivia is free to have her own mind.

- Olivia stands up to her father who calls her a princess.

- Olivia doesn’t conform to the Western Beauty Ideal of prettiness. She is confident even when dressed up as a warthog.

IN THE NOT SO MUCH COLUMN

- The gender roles of the parents in the Olivia series are far from feminist. Take another look at the breakfast table scenes, in which the father is always reading the paper and the mother is always tending to the kids. Take a close look at the mother’s face in the image below. Does she look happy about this situation? Why not??

Despite being an avid reader of the newspaper, who is it with the job/privilege of reading picture books to Olivia each night? Apparently we have a crisis of boys and reading. Why aren’t the pig parents alternating the nightly reading to Olivia? Perhaps the father is busy tucking the younger siblings into bed? Unfortunately we don’t see that on the page, so we are left to conclude that keeping up with current events and politics is a male domain whereas reading fiction to young ones is a female one.

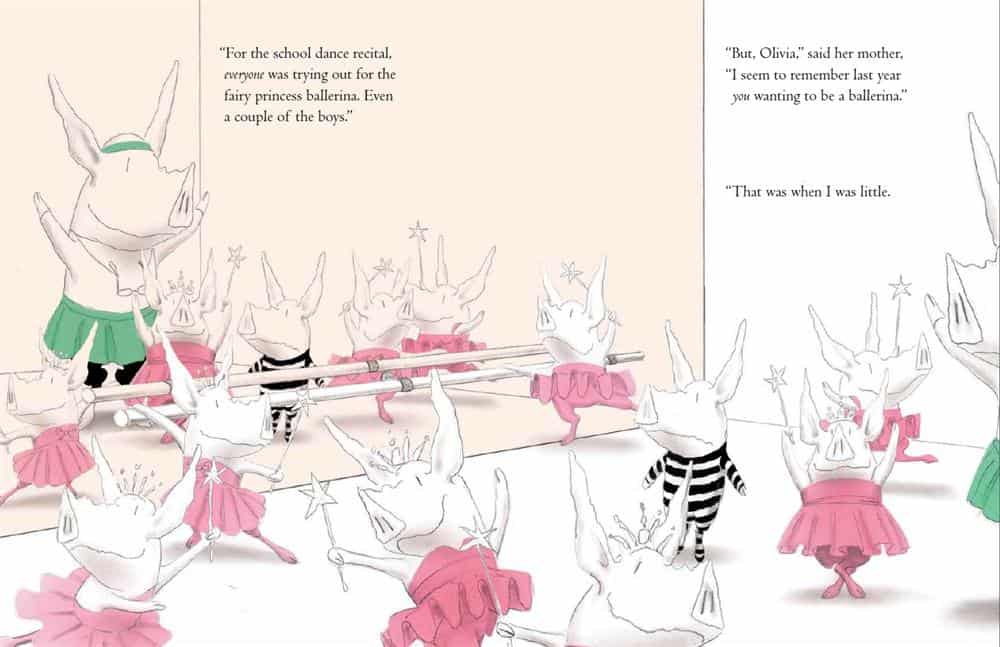

“At Pippa’s birthday party, they were all dressed in big, pink, ruffly skirts with sparkles and little crowns and sparkly wants. Including some of the boys,” Olivia explains, carefully adding that some boys like to dress up pretty, too. Later, she explains, “For the school dance recital, everyone was trying out for the fairy princess ballerina. Even a couple of the boys.” At first glance this might seem inclusive. But doesn’t the word ‘everyone’ cover it already? By tacking on, twice, that a couple of boys were included in this pink business, the unintended consequence is that these boys are othered. Part of me wishes the boys could have been depicted via the illustration. But then I thought of the practicalities of this; how do illustrators even depict gender in picturebooks, given that everyone is wearing pants (and even then, genitalia doesn’t equal gender)? They do it with pink: pink for girls, every other colour for boys, who are the default. Maybe bows on heads and extra eyelashes for girls. So without saying in the text that some of these pink characters are actually boys, the reader would never know. Could this inclusiveness been achieved another way? I think so. It just takes a bit of imagination. Since the author is already using Western gendered names for Olivia’s family, he could have included a scene or two in which pretty pigs with boy names just happened to be in the scene. In general, if you want to express a political message in a picture book, it’s best not to preach it. And even though this entire portion of the book is a monologue that ostensibly comes from Olivia, it’s a straight didactic message nonetheless.

Pink is obviously ubiquitous in girl culture — no one would deny that. I also find that when little girls dress up in pink their behaviour actually changes. They’re less keen to muddy their pretty clothes, which hampers their activities. They seem to become more coy and aware of the outside gaze when out in public dressed as a princess. But I still don’t like to see all those little girls dressed in pink run into the corner when Olivia enters the room dressed as a warthog. This suggests that if a little girl does dress in pink then she is also cowardly. I don’t like to see that correlation underscored in fiction, because what we’re really doing is showing how little girls in pink are meant to behave, and the only way you can not behave like that is by dressing in something other than pink. This isn’t actually an option for lots of little girls, whose parents ONLY dress them in pink!

Here’s something I don’t quite understand: Even though Olivia has shown us that she’s more than capable of thinking outside the gender box, when she goes to sleep at night what does she dream of doing? “Maybe I could be a nurse and devote myself to the sick and the elderly,” or “maybe adopt orphans from all over the world!” Olivia dreams of caring for others, in other words. Next she does think she might be a reporter, exposing “corporate malfeasance”, but I’ll argue that showing the female Olivia on the periphery of a scene with two male pigs is yet another scene in which gender roles are reinforced rather than challenged. (Rich baddies = male; underdog goodies can be female.)

One could also argue that there’s nothing wrong with being a princess. When all the other girls in a story are doing the same thing, the message risks sounds like ‘not like other girls’ pseudo-feminism.

This particular Olivia story has an overtly feminist message, but when you look more closely, at the pictures as well as at the words coming out of Olivia’s/Falconer’s mouth, you’ll find the feminist message somewhat undermined.