Birgitta Sif is a picture book illustrator originally from Iceland, now living in England. So far she has produced four books. Oliver was first published by Walker Books 2012.

A nice touch is that the opening page says ‘This adventure belongs to’, where most books say ‘This book belongs to’, leaving space for the child owner’s name. This already feels a lot more exciting. Perhaps this is something Walker books has decided to do with all of their publications recently?

THIS ADVENTURE BELONGS TO

That said, this story is not what I would call an ‘Adventure story‘ in the technical definition of the genre. This is a mythic journey: The (male) hero leaves home and goes on a journey to find himself, meeting people and changing in the process. Still, that’s not what most people think of when they think of a mythic picture book, so it’s probably best the opening page doesn’t say ‘This myth belongs to…’.

It’s not unusual these days to find picture books with this few words, but even so, this stands out for its brevity — more than half of the story by far is told by the pictures. My reading of the story is that Oliver is on the autistic spectrum, though readers will bring their own interpretations, I’m sure. He may just be a highly imaginative little kid with some social anxiety issues. Since we don’t hear any dialogue, it’s possible that Oliver does not speak.

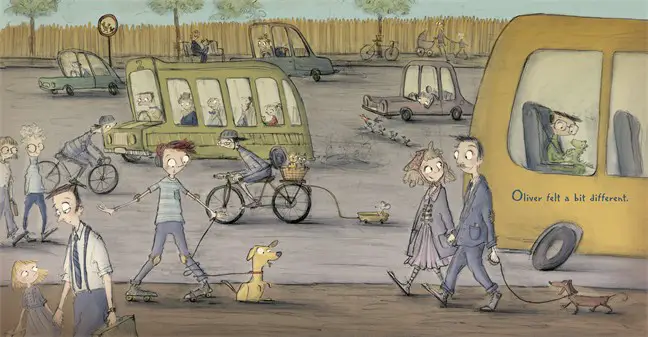

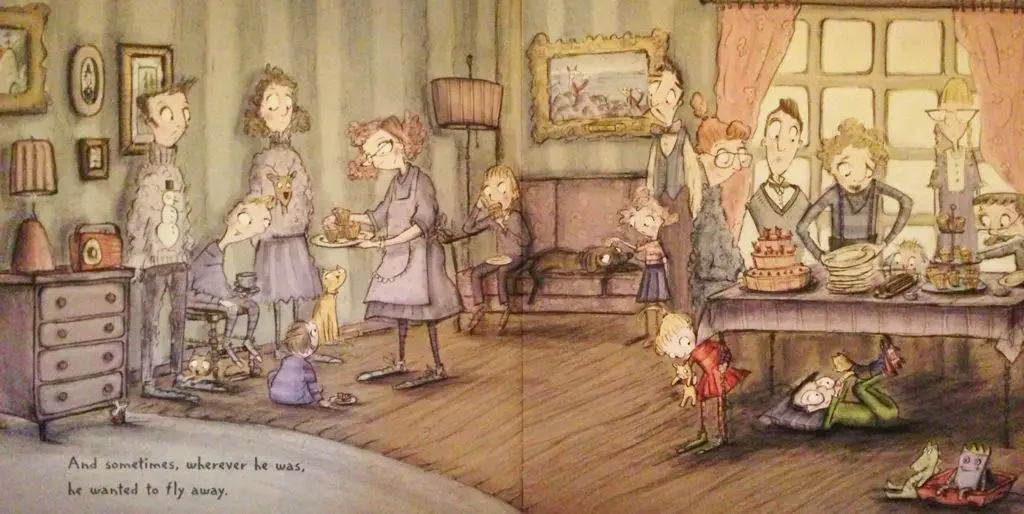

Here is the opening double spread, in which we are told that ‘Oliver felt a bit different’. In each of the illustrations we’ll see just how different.

STORY STRUCTURE OF OLIVER

SHORTCOMING

Though not exactly unhappy about it, Oliver is without real life friends, consoled only by his imaginary world and books. He needs to find a real-life friend for the reader to feel happy to leave him. The ideology of this book — as in any popular children’s book — is that having real life friends is vital, even if you do have a rich imaginary world.

DESIRE

Oliver wants company. This part of the story structure has interesting politics: If we’re to read this as a story about autism, it’s not in fact clear that Oliver wants a human friendship because he seems quite happy being in his own head with his imaginary friends. He looks happy enough on the interior title page, hilariously fishing for a fish he’s crafted himself out of paper. When he finds Olivia at the end of the story, however, the neurotypical reader will be happy for him.

I’m always a bit skeptical about endings — I’ve found that neurodiverse kids can either be best buddies OR butt heads once they find themselves thrown together! It remains to be seen how these two get along… Though I’m not holding out for the sequel!

AUTISM AND GENDER

It’s interesting to me that this particular gender dynamic was chosen for the story. What if this had been a story about Olivia, with Oliver found at the end? It’s so prevalent in story telling that most people don’t notice it anymore, but the cultural narrative is that the male of the species goes out and finds a female partner while the female passively waits for ‘her prince to turn up’. This is from fairy tales of course, but it goes back 3000 years at least with The Odyssey. Even in modern sex education we teach kids that the egg sits passively around waiting for sperm to actively swim and find her. (We assign genders to the egg and sperm themselves, though this itself is ridiculous.)

The other current cultural narrative is that boys are four times more likely than girls to be autistic. It would seem this is not true. The trend is certainly not going that way. First, Hans Asperger declared in 1944 that Aspergers only affected boys. Next we realised girls could indeed be aspie, but boys were 15 times more likely to be so. Tony Attwood wrote in his book The Complete Guide To Aspergers Syndrome that he suspects the ratio is more likely to be 2:1 if girls were diagnosed more frequently, or if the criteria were changed to include the ‘girl version’. Well, Aspergers no longer exists as a separate thing in the DSM-5, but I predict within the next few decades we’ll be hearing that girls and boys are autistic in a ratio of 1:1. I doubt this will happen before the exact genetic causes of autism are uncovered, since girls are ‘research orphans’, in many things, autism included.

Tony Attwood also points out that it’s easier for aspie boys to find buddies than it is for aspie girls. Boys are often ‘taken in’ by groups of girls, accepted for their differences because they are a boy, whereas aspie girls who are different find no such solace among their own gender, and might not find it with boys, either. Even with schools that specialise in autism, girls will be vastly outnumbered at the present ratios.

It’s also interesting, I think, that at the end Olivia embraces Oliver and plays what’s basically called ‘dolls’ with him — something completely typical for girls, which would not mark a girl out as different at all, despite any atypical neurology. It’s also common for girls to be completely absorbed in books. But when these behaviours exist in a boy, he feels different — from other boys, presumably (and I read him as autistic).

OPPONENT

Oliver against the world! The absence of an easily definable opponent is the kind of thing that gets children’s stories described as ‘quiet’. (Or boring.)

Perhaps Oliver’s opponents are the toys, human stand-ins, who eventually let him down one night when he seems to realise they’re not listening to his piano performance.

One evening he played the piano for his friends, but no one listened.

Notice that this is the point in the story when we switch from iterative to singulative expressions of time. Everything prior to this point is the set-up — the rest of the book is the story that happens on this particular occasion.

PLAN

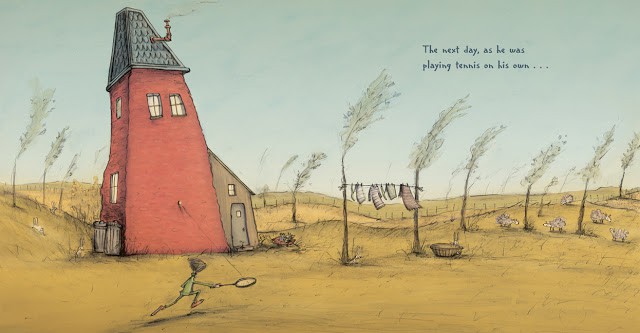

He forgets about his stuffed toys and goes outside to play tennis against a wall, with himself. Presumably he hasn’t tried playing outside before (otherwise he would probably have discovered his neighbour before). So a sub-ideology seems to be: Kids are better off playing outside rather than too many books. (Lack of sunlight indeed contributes significantly to short-sightedness, which is apparently how Australian kids are avoiding the juvenile myopia explosion that’s happening in other countries around the world — Australian sunlight is very bright and a little goes a long way.)

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle happens inside his own head, mostly on one page:

So Oliver set off on another adventure, through the wild jungle, over the river, up and up the mountain, until he found a narrow gate to somewhere new.

It’s important that such symbolic landmarks are picked — perilous ones — because it lends the story the requisite (imaginary) big struggle (against nature).

Honestly I feel this ‘big struggle scene‘ needed to be illustrated as well as told, if we are to believe that going through the gate is a big deal for Oliver.

ANAGNORISIS

If he goes through the gate he will find a friend. The gate, of course, is a metaphor for ‘going outside himself’ — getting past the wall that exists between himself and the outside, social world. The gate seems even more of a symbol when you re-read the story and realise Olivia has been present in a number of the previous spreads all along — reading beside the pool, reading at the library, checking him out under the table, she with her teddy bear and he with his own stuffed toy.

NEW SITUATION

Oliver now has a real-life friend, and the wonderful thing about this ending is that he keeps (and shares) his imaginary friends, too. Any picture book creator wouldn’t give up their own imaginary worlds for the world!

MODERN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE AND NOTIONS OF REPLACEMENT

I’m reminded of picture books in which beloved pets die. In older books, the family goes out and gets a new pet and everyone is happy again, as if what’s needed is some sort of ‘replacement’, to fill up some sort of void. More modern stories for children have moved away from ‘instant replacement to compensate for loss’, and here, too, Olivia doesn’t ‘replace’ the imaginary ones — she complements. This probably parallels modern thoughts on psychology, and the various stages of grief.

YELLOW BUSES AND SPECTACLED BOYS

Because of the positioning of the boy tied up with the dog in the image above (that rule of thirds thing) it’s easy to think that Oliver is actually the boy all tied up with the yellow dog, but Oliver is actually the one sitting on the yellow bus, right above the words. (Have you noticed there’s an American-export unwritten rule that in picture books from all around the world school buses are yellow?)

In picture books, when children wear spectacles, we know to expect a certain kind of kid. He may be bookish or nerdy or otherwise different. (Are kids on the autistic spectrum more likely to need glasses, or is it just in picture books? Apparently, in real life, the opposite is probably the case.)

NEGATIVE SPACE = ISOLATION/DREAM SPACE

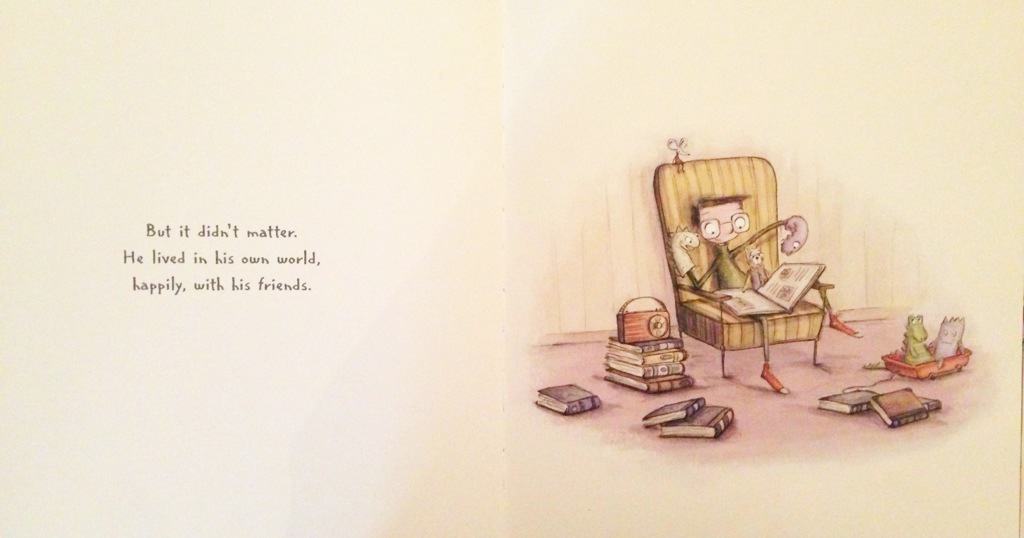

Sure enough, here we see Oliver reading a book, with animated hand puppets for company, and books all over the place to suggest that reading is his favourite thing to do.

Here, compared to the other very busy spreads full of action and character, we have a quiet scene with mostly negative space. The whiteness forms the edges of a kind of dream state — Oliver is not really present in the real world. The choice to leave lots of white space is far more effective than if the pages had been filled with the rest of the room.

THE SYMBOLISM OF THE MICE

The page above also includes the fantasy element of the little mouse wearing clothes who sits on the back of the chair. (It’s great fun to dress mice in clothes and is almost impossible not to do if you’re an illustrator!) In Oliver’s mind, not only his toys but also the surrounding rodents have come to life. These mice are with us throughout the book, except when Oliver is feeling lonely. This is a really nice variation on the widely used technique illustrators use, of creating a parallel story with (usually) a pair of small animals, turning the book into a bit of a toy book by inviting young readers to perform a ‘Where’s Wally’ type search on each double spread. Here, the two mice also have a deeper, symbolic meaning:

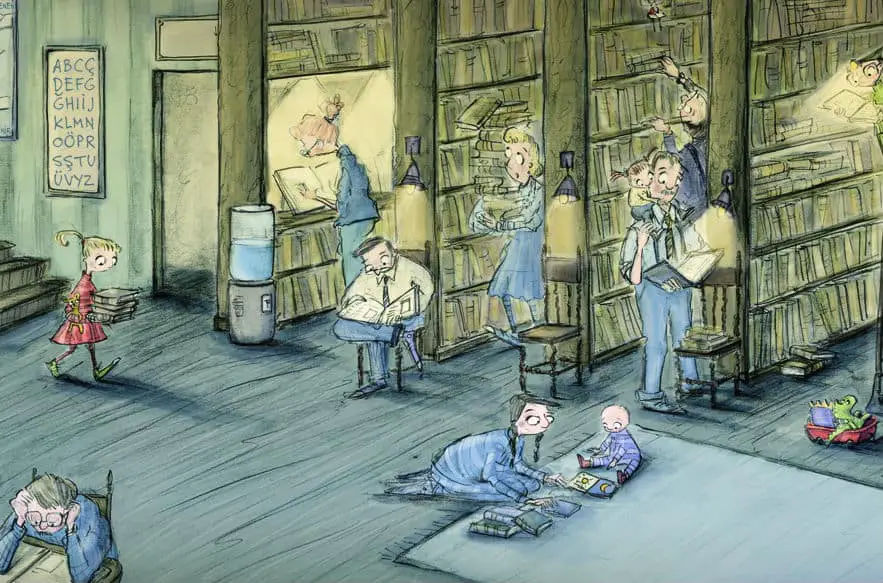

In this humorous illustration we see that even at the library Oliver behaves differently from the crowd — having climbed up a shelf, reading by the light of a head torch. Is that the Icelandic alphabet on the wall behind Olivia? I guess this story is set in Iceland. On the wall of the library (cut off here) we can see a poster: “If you can read you can fly”. Ironically, it’s not reading that allows Oliver to fly; it’s going outside to play ball.

This looks like an illustration of social anxiety to me, curling up under the dining room table when the house fills up with relatives. Notice all the pets in this Christmas gathering — more than I’ve ever seen at one of our family get-togethers! But these aren’t regular pets — notice how illustrators will often draw pets with human-like whites and a small iris, so that we get to see where they are looking. This gives illustrated pets so much more human expression than in real life animals, in which their iris and pupil fills their entire visible eye.

I love this illustration of Oliver’s house from the outside. Which way has the wind been blowing? Looks like the house sways the opposite way from those trees. Oliver — and his house, which is a building version of him — leans the opposite way. Not even the most natural of elements can ‘make him bend the right way’.

THE SYMBOLISM OF THE HOUSE

The house is almost the shape of a lighthouse, which is typically symbolic of isolation and loneliness, standing alone, working all night, guiding equally lonely ships home into the safety of a bay. There’s no actual sea in this scene, but the landscape looks just as barren and lifeless. If Oliver really lived here, would he be attending a regular school? Well, no. This is a symbolic house and landscape. We have already seen the inside of the house and unless it’s the Tardis, we know it’s a lot more roomy.

That said, do a Google image search for ‘iceland house’ and there does seem to be something very Icelandic about this illustration. You can always tell how much it snows by the roofs — the steeper the roofs the heavier the snow. The bereft landscape suggests a recent snow blanket, since melted. The wind itself suggests no shelter.

FURTHER READING

Meesha likes to make pictures and create things inspired by her imagination, but when it comes to making friends, Meesha doesn’t know what to do. She says or does the wrong things, and she just doesn’t connect with other kids. When Meesha is invited to a party, she finds herself off to the side playing by herself. A boy named Josh is interested in her playing, and they slowly begin to play together.