Young readers love to hear about naughty children. If this were a story by Roald Dahl or Edward Gorey, the naughty Millie would definitely have met a nasty end, but this particular naughty child remains the apple of her parents’ eyes. Since all children have bad thoughts sometimes, this story is a comfort-read, and would be especially so as a bedtime book at the end of a bad day.

That said: Picturebooks in which a naughty character goes unpunished have a particular marketing problems that adult books about retribution don’t have:

I usually really like and respect John Marsden’s work, but I really don’t liek this cute little picture book. Great drawings from Sally Rippin. But the content! Millie is an odious, conniving, lying child, who gets away with all her hideous behaviour. Even when she’s caught in the act everyone just says, “we all love Millie”?? Oh please.

a 1 star review of Millie from Goodreads

For this reason, the biggest challenge the author and illustrator face when constructing a ‘child is mischievous/naughty’ story such as this one is how to end it. In novels for adults, the criminal is much worse, but almost always gets caught. (See: The entire crime genre.) In literary fiction, people might do bad things but we tend to see both sides and shades of grey in their motivations, so if criminal behaviour doesn’t go punished, the book ends up saying something on bigger life questions of fairness and chance of circumstance. But in picture books for toddlers, what are the unspoken rules about stories in which the main character does bad things?

I have pondered this question before, after looking at some (adult-gatekeeper) consumer reactions to This Is Not My Hat by Jon Klassen. Professional picture book critics unanimously love This Is Not My Hat, because the professional consensus is that children are capable of understanding that sometimes bad behaviour might go unpunished, without necessarily replicating bad behaviour in their own lives, thinking that they, too, will ‘get away with it’. In Marsden and Rippin’s Millie, the main character does indeed seem to ‘get away with’ her bad behaviour. Her parents continue in their delusion that Millie is perfect.

An older book featuring a character who displays bad behaviour but who goes completely unpunished is Just For You by Mercer Mayer. Just For You — insofar as I can gather — seems to have avoided the same criticisms that more modern versions garner. Indeed, the Just For You book is considered one of the early ‘classics’ in Mercer Mayer’s Little Critter series, and continues to sell well. Millie was never released in paperback, and may soon become a hard-to-find book.

What are the differences between Just For You and Millie (apart from era/marketing/luck of circumstance — of which there is always some, in publishing)?

JUST FOR YOU BY MERCER MAYER

- Little Critter is younger than Millie. There’s some evidence to support the idea that children lose their ‘irresistible baby cuteness’ at the strangely specific age of 4 and a half. After 4.5 years, children (at least in the West) are expected to behave in a more responsible, less egocentric manner.

- Little Critter is an only child. A baby comes along later in the series, but has not yet been displaced as the most vulnerable cute character in the story. It’s possible that the reader would expect more of Little Critter if there were an even younger, even more vulnerable Critter, in which case he would seem older to us than he really is. We would therefore expect more of him. This is possibly the same dynamic that plays out in real-life, influencing the different expectations we have of eldest children versus youngest.

- Little Critter’s intentions are shown to be honourable. We’re told via the text that he really does want to help his mother, but his age means that he can’t quite focus or manage the dexterity required for the task.

- Written in first person, from Little Critter’s point of view.

- Little Critter is completely redeemed at the end because the thing he is good at — without fail — is giving hugs and kisses.

- I’ll add that Little Critter is coded as male, even though some may argue that despite the masculine pronoun he is ‘genderless’. I don’t buy the ‘genderless’ argument, and argue that female coded characters in books, as in real life, are expected to be more empathetic, helpful, well-behaved and mature. This is on the back of ‘boys will be boys’ culture. See also: Must characters be likeable?

MILLIE BY JOHN MARSDEN AND SALLY RIPPIN

- Millie is a little girl, not a toddler. Whereas Little Critter is still wearing one of those jumpsuits with easy access for nappy changes, Millie is wearing little girl clothes. She’ll be wearing those clothes until she reaches adolescence. We expect better from a child of Millie’s age, because we can’t really tell if she’s 4 or 7.

- Millie has a younger brother, who absorbs the bulk of reader sympathy when Millie cages him inside her doll’s house. More gender issues here, probably.

- The reader doesn’t know Millie’s intentions. I would argue that the reader has more than enough clues from the facial expressions within the illustrations, but adult consumers seem often to fail miserably at reading pictures, focusing too heavily on the words. I would argue that Millie’s intention is to have fun. When she locks her baby brother in her doll’s house, she does not think she’s being mean — she probably thinks she is being nice by including him as a character in her game. When she ‘tidies’ her room by shovelling everything under her bed and duvet, she may well think ‘out of sight out of mind’. When we see her brushing the dog’s teeth instead of her own, she actually demonstrates empathy by thinking that the dog needs his teeth brushing too. (The vet has since told me that yes, dogs do need their teeth brushed.)

- Written in third person by an unseen narrator, who wryly delivers a story about a naughty girl knowing full well that she has deluded her oblivious parents. As a culture, we have little tolerance for parents who fail to see bad behaviour in their own children. Whereas Little Critter has a clear dual audience in which the child feels loved despite their failings, and the adult co-readers are reminded that although little kids are a trial, they compensate for all the nuisance by offering unbridled love and affection, the dual audience in Millie works with a different mechanism altogether; adult co-readers may well be reminded of certain parent-child dynamics in their own real-life circles.

- Millie’s behaviour grows worse as the book progresses, not better. There is no cute scene at the end. In fact, the last we see of Millie is on the endpapers in which we see a pair of grubby hand prints. We are told that Millie will continue to be naughty — and the trajectory indicates that Millie will only grow worse — and we are offered none of Millie’s redeeming features. Millie’s character change is from bad to worse.

Does the young reader need to see bad behaviour go punished in picture books?

Do we need reassurance that any bad behaviour will not continue? Is there a foolproof way of creating an enduring story about a naughty character and escape significant consumer criticism? It seems not. Let’s consider the enduring appeal of Where The Wild Things Are, in which Max is punished (albeit right at the start of the story — the act that leads to the punishment is not the main act). Can you think of other picture books in which a child is punished after misbehaving?

Still, there may be some takeaway points:

- In the most popular stories about naughty children, the naughtiness is borne of fun, curiosity or plain old misunderstanding. That’s not to say that ‘inherently bad’ child characters aren’t adored also — that main characters of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, each a symbol of a deadly sin. Roald Dahl is not without his detractors. Some think he took an unhealthy delight in scaring children.

- It’s easier for the reader to identify with naughty characters who are toddler age rather than school age and older

- Especially if those characters are shown with clear good intentions

- And especially if they are the youngest character in the story.

- One way of creating reader empathy in any story is by surrounding that character with fictional characters who love them. The reader may not know why these good characters love the bad one (cf. Scarlett in Gone With The Wind) but the fact that they are loved shows the reader that they are somewhat loveable. Millie is certainly loved, but perhaps there is a limit to this rule-of-thumb. The resigned and exasperated but ultimately loving look on Mother Critter’s face is perhaps better when it comes to dual-audience reader empathy in picture books.

- Safer to show the reader that the naughty character is inherently good, whatever that means.

- If not, safer to show some punishment, to reassure a conservative audience that bad behaviour will not continue beyond the story.

I’m not necessarily arguing for ‘safety’ when it comes to the creation of picture books. In fact, there is a strong argument for keeping picture book world more real.

COMPARE MILLIE WITH

Other books about naughty children abound. Love You Forever (links to a tongue-in-cheek run-down at Cracked.com), The Berenstain Bears and the Bully, The Rainbow Fish, Because Your Daddy Loves You, Arthur’s Nose. Another of my favourites is Dreadful David. Interestingly, David is indeed punished here. He receives a smack on his bare backside and is sent to bed by his loving grandmother. I have wondered, reading this out-of-print book published in 1991 if such a bare-backsided scene would be admissible in a picture book published 2015. Schools have not been allowed to hit children since the late 80s/early 90s in this part of the world.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION OF MILLIE

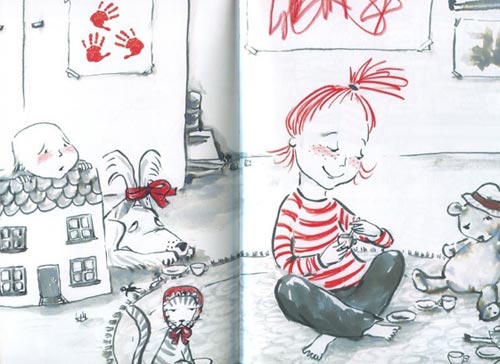

The Colour Red

As can be seen from the picture below, the limited colour palette allows red to shine. The red of Millie’s hair and shirt functions as a symbol of naughtiness. Notice that in the room, the red objects highlight where Millie has been naughty. Though technically her handprints and scribbles are on posters and therefore not ‘acts of naughty’ in the most straightforward sense, we see on subsequent pages that Millie does scribble where she should not. She most definitely is the sort of child who leaves messy handprints behind for others to clean up.

But it is mischievous rather than naughty to put a baby’s bonnet on a cat, tie the dog’s ears up with a ribbon and imprison the baby inside a doll’s house, presumably as one of the cast of characters in Millie’s imaginary game.

Note also the way the teddy bear gazes straight at the ‘camera’, inviting the reader to take part in our admonishment of this naughty kid. The facial expressions are depicted perfectly. The baby looks distraught, the dog looks resigned, the cat looks side-eyed and Millie looks quite content.

What other picture books can you think of with a remarkable use of red?

The red of fire conventionally implies both intensity and warmth. Consequently, although red is the only color in Dr. Seuss’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas, the red of the Grinch’s eyes clearly implies anger, while the red of the sky as the villagers sing happy Christmas songs implies warmth and love.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures

See also: Wolves by Emily Gravett

White Space

You can tell from the front cover that Millie makes judicious use of white space.

I might try to persuade you that in this story the white space symbolises absence — absence of punishment, or the ‘clean slate’ Millie enjoys in the eyes of her parents.

More practically, the white space juxtaposes scenes full of action — Millie’s messy bedroom, Millie’s wild backyard play. Millie is naughty, nothing happens. The graphic design echoes this story rhythm.

White is also a nice contrast with the red, allowing the red to pop.

STORY SPECS OF MILLIE

Published 2002, Pan Macmillan, Australia

Written by John Marsden, best known for his many, hugely successful YA novels, especially the Tomorrow When The War Began series

Illustrated by Sally Rippen

Book designed by Sydney based i2i Design. I find the job of a book designer fascinating; how would the book look different if it were up to the illustrator and publishers alone? Many of the big-prize winning picture books in recent years have been illustrated by people with a background in design, which makes me think that hiring a designer to complement the page layout of illustrator is perhaps more necessary these days.

WRITE YOUR OWN

Can you remember a time your child self behaved with honorable intentions in a way that was misinterpreted by an adult caregiver as naughty? I remember as a five-year-old being scalded by a teacher for drawing massive full-stops at the end of my sentences. I’d drawn them large so that my elderly teacher would be sure to see them even without her glasses on. A few years later I gifted a younger boy an exuberant ride on a round-about at the park, but he wasn’t holding on tightly enough and went flying. I still remember the glaring hatred in the eyes of his mother. I’m sure all children have these experiences — it’s just a matter of remembering them!

What are your own ‘rules’ when it comes to enjoying (or not enjoying) picture books in which a child character is naughty? Though it’s somewhat of a false dichotomy, are you on team Caldecott, or team Goodreads?