Madeline and the Gypsies is one of the sequels to Madeline a classic picture book by Ludwig Bemelmans.

Ludwig Bemelmans named his fictional little girl after his real-life wife. Although if you know any Madelines, you may find her name is spelt (more traditionally) with an extra ‘e’, as was Madeleine Bemelmans’ name. This series itself has probably contributed to the more modern, simplified spelling. Although Madeline was named after Bemelmans’ wife, the character was inspired by the activities of his only daughter, Barbara.

Ludwig died quite young of cancer of the pancreas aged 64 back in 1962, but one of his grandsons is also a children’s book writer/illustrator and has contributed some extras to the series.

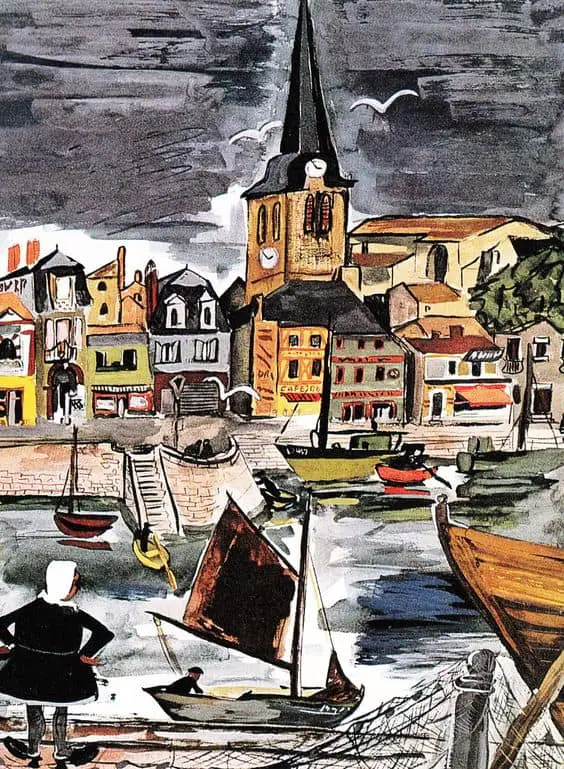

Ludwig’s first language was French and his second German. That explains the fetching but unusual grammatical constructions of the English.

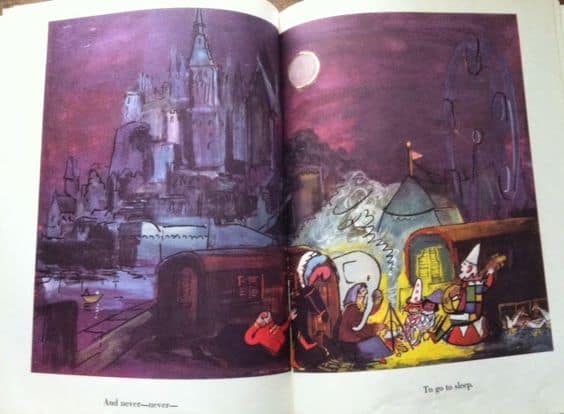

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION

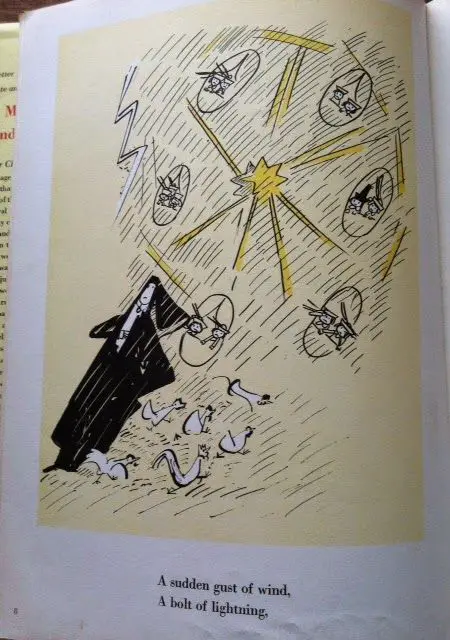

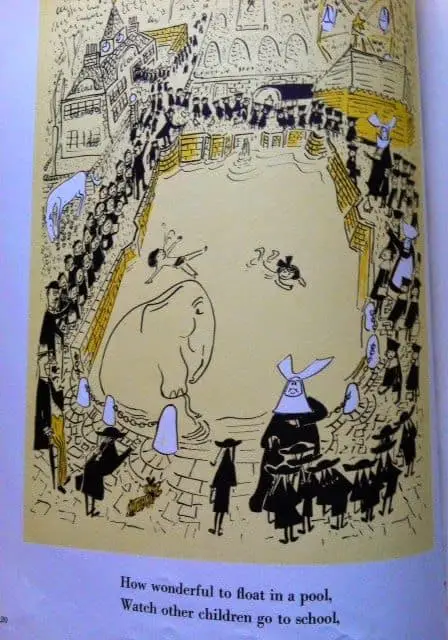

- ink and watercolour

- probably dry brush in places

- bold, quick markings

- impressionistic tendencies

- a mixture of coloured and monotone plates

- dark colour scheme, not bright and cheerful like some people think children’s illustrations should be

First published (in its full length) in 1959, this is a children’s book from the Second Golden Age of children’s literature. Accordingly, improvements in colour printing technology made it possible to produce cheaper multicoloured plates, and the Madeline books are not quite full colour. (I guess the yellow and black pages were to keep printing costs down rather than adding any symbolic meaning to the story.)

You can probably tell from the style of the illustrations that there is nothing specifically childlike about this work. It looks quite at home in The New Yorker and in an art gallery, which is where a lot of Bemelmans’ work spent time. This guy wasn’t “just” a children’s book writer and illustrator — a lot of his work was produced for adults.

However, Bemelmans wasn’t formally trained to a high level. He took art classes now and then and his father was a painter but his style is self-taught. (I suppose all great artists are, in the end, self taught.)

Bemelmans said that he felt he had no imagination and was only able to draw from real life inspiration. I’m not sure any illustrator is able to draw entirely ‘from imagination’ — even the very best concept artists are drawing from the real world; the difference may be that concept artists are good at placing unexpected realworld elements together. Other artists have a great memory for detail and don’t need to look at their source material in order to reproduce it.

CHARACTERS

Like other books from this era, the (quasi) opponents turn up in the form of gypsies, though I do like this particular story in that the gypsy mama turns out to be a goodie, as does the nun who runs the orphanage. Generally in children’s literature these two positions make the women default baddies.

But this story is carnivalesque. In fact, there is no better example of carnivalesque kidlit — it literally takes place at a carnival. There is no real baddie in a carnivalesque story for young readers.

Each book in the series opens with the information that Madeline is the smallest of all the girls. This is a fairytale technique, in which the smallest character is designed specifically to be the character who engenders sympathy — a proxy for the youngest child of three.

Interestingly, Madeline is different from all the others because of her red hair. By the time this book was published there was no longer the view — as there had been in L. M. Montgomery’s time — that red-headed girls were akin to witches and inherently dangerous.

STORY STRUCTURE OF MADELINE AND THE GYPSIES

SHORTCOMING

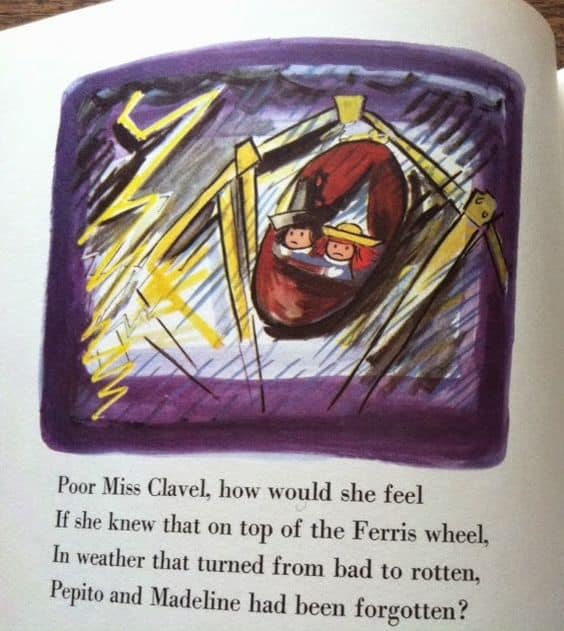

Madeline is an orphan and gets stuck, rather metaphorically, at the top of a ferris wheel during a thunder storm.

DESIRE

At first Madeline just wants to get off the ferris wheel, but after the rescue (by the gypsy mama and Pepito, her boy companion) that it would be much more fun to follow the circus than to go back to the orphanage.

OPPONENT

The opponent is the orphanage, personified by Miss Clavel, the nun. Miss Clavel is not an evil person at all — she has been worrying herself sick about Madeline, but when she receives a postcard she stops worrying about Madeline and, rather comically, worries that she’s forgotten how to spell. The real enemy here is formal education which stunts creativity and curbs adventure.

PLAN

The Gypsy Mama has a rather unusual plan — when she sees (in her conveniently accurate crystal ball) that Miss Clavel is coming to get Madeline back, she dresses Madeline and Pepito as a scary lion so that Miss Clavel will be scared away.

BIG STRUGGLE

Madeline and Pepito come close to death when, disguised as a realistic lion, they meet a man with a gun, who might just as well have shot them as run away in fright.

ANAGNORISIS

The anagnorisis comes when Madeline sees Miss Clavel and the other little girls in the front row of the circus. She realises how much she’s missed them. Back at home, “Here is a freshly laundered shirty. It’s better to be clean than to be dirty”. Home has its advantages just as the wilderness has its advantages. There is no hierarchy anymore.

NEW SITUATION

Miss Clavel will now be extra careful about counting all the girls to make sure none goes missing!

FURTHER READING

Bemelmans remains best known for his children’s books about Madeline, but he also published a series of stories inspired by the author’s time as a waiter in the expensive French restaurant of a New York Hotel in the 1920s and 30s. (A fictionalised Ritz Carlton.) This collection exhibits the author’s dark humour, as well as typical racial stereotyping of the time — the same biases which made the word ‘gypsy’ seem okay.