Just Me And My Puppy by American author-illustrator Mercer Mayer is worth a close look because, like many others in this long-running series, it is a wonderful example of ‘counterpoint irony’ in picture books.

Though the title may annoy purists, the grammar of the title foreshadows a story told from the point of view of a toddler-aged creature. As a child I always wondered what ‘critters’ were. I thought a critter must be some sort of American animal in particular.

Apart from ‘counterpoint irony’, another useful concept when considering any disconnect between words and pictures is ‘symmetry’. Nikolajeva and Scott have attempted to create a sophisticated taxonomy of picturebook interactions (between words and pictures) and came up with a sliding scale. Symmetry is at one end, in which the pictures pretty much repeat what the words have already explained. At the other end is ‘contradiction’, in which the pictures say something completely different from the words, often creating irony or humour. The problem with having ‘symmetry’ at the extreme end is that pictures cannot help but say more than the words, since ‘a picture tells a thousand words’ (or thereabouts). So there will never exist a perfectly symmetrical picturebook.

STORY

In Just Me And My Puppy, the words tell us a sweet but bland story about a child who is care for and train a new dog. The pictures tell a difference story altogether: the story of a boy who is struggling to control an exuberant and disobedient puppy. Readers familiar with the innocent, willing-to-please Little Critter will see that the puppy is simply a more exaggerated version of the Critter.

WONDERFULNESS

Broadly speaking, irony is a difference between what was expected and what actually happens. In literature, irony is a rhetorical figure based on a deviation from the dictionary meaning of words. Picturebooks make use of their own specific kinds of irony. Irony cannot be expressed by illustrations alone, but can be achieved when the words in a picturebook don’t match up with the pictures, creating what academics have called an ‘ironic counterpoint’.

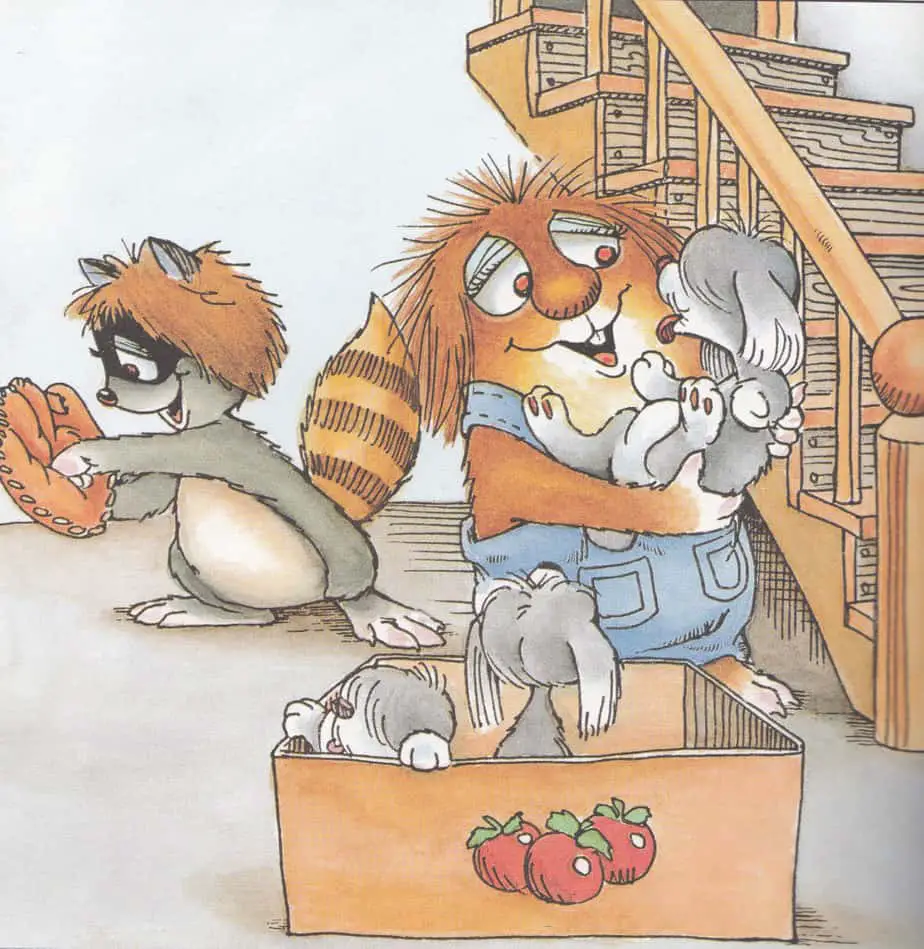

How does this counterpoint work, exactly? Mayer begins the ironic counterpoint on page two. Page one sets the story up, with the protagonist swapping his baseball mitt for a puppy. The picture does not contradict the words, as we indeed see a box full of puppies and a raccoon pleased with his new baseball mitt. Naturally, there is more to the illustration than there is to the words — we see they are in a basement, that the box of puppies used to hold tomatoes, that a surprised spider is watching on. But this pictorial elaboration is not a counterpoint so much as an expansion.

Come page two, we are told, ‘My baby sister liked him right away.’ But we see a puppy jumping all over a baby, who doesn’t look pleased at all.

Page three is less ironic: ‘And, boy, were Mom and Dad surprised! They said I could keep him if I took care of him myself.’ The interesting thing is, we now mistrust the little boy’s version of events, and adult co-readers (especially) will be wondering how that conversation really went down. Mayer is very good at depicting facial expressions, and the parents in the Little Critter books manage to so often look resigned, disappointed and skeptical, but loving at the end.

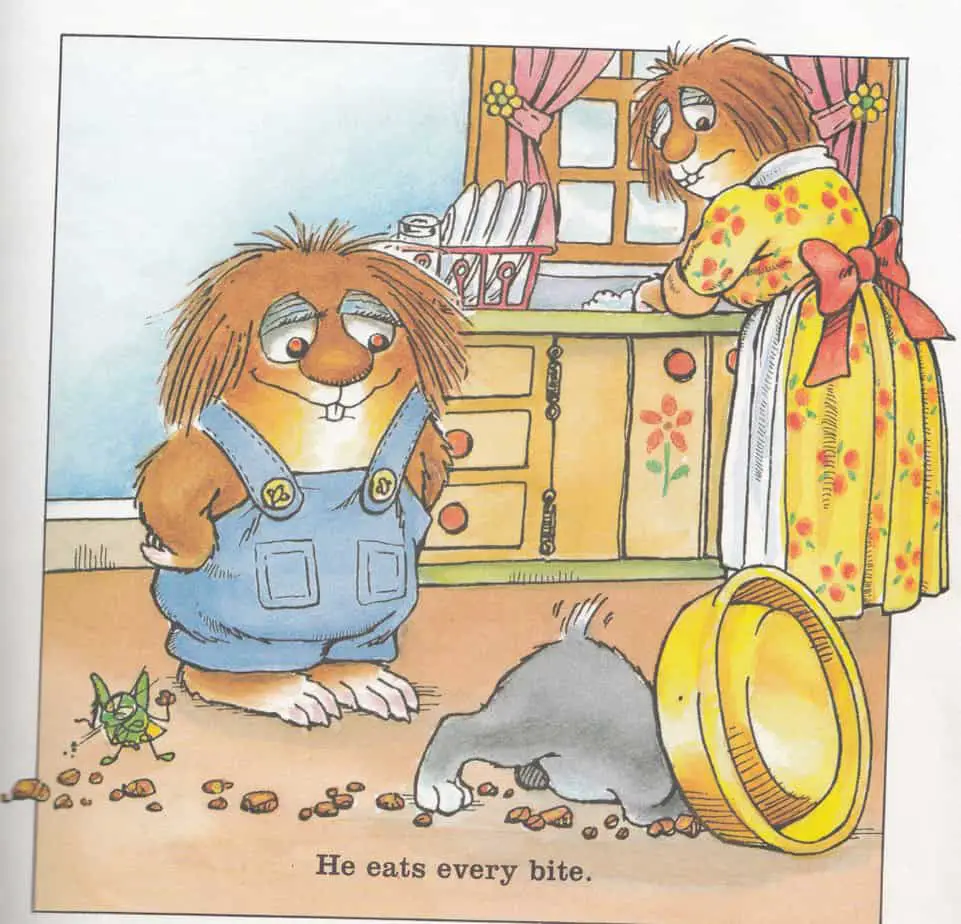

The ironic counterpoint heightens as the Little Critter trains his puppy. ‘He eats every bite,’ we read, noting that there is dog food spread in a trail right across the kitchen floor. ‘I am teaching my puppy how to heel’ shows Little Critter tangled in dog lead with the puppy pulling uncontrollably, and so on.

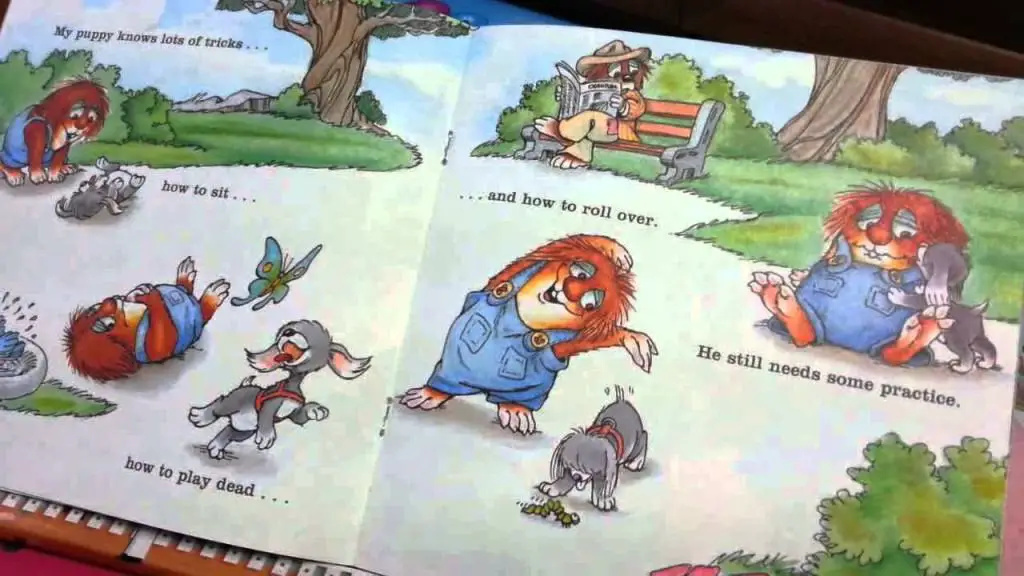

After a few pages of unsuccessful episodes, we see a full-page spread set in a park. Now we see a ‘snapshot’ scene, of four Little Critters and four puppies, and we take from this that all of these scenes happened, but not at the same time.

Notice how Little Critter is dotted across the page — the reader is given a clear sequence of events. Sometimes a sequence of events depicted like this is not important — events can happen in any order. Personally, I like my eye to be guided around/across a page. I like to know what’s meant to come first. Notice also the white space across the park scene. The path is the white space.

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION OF JUST ME AND MY PUPPY

Not only do Little Critter books tell two different stories via the words and the pictures; the pictures contain a subplot story about a spider and a grasshopper who readers will be keen to locate once they realise these unnamed characters are a regular instalment on each page. These characters never speak, but they have facial expressions which offer the reader further emotional cues. Mercer Mayer has a knack for depicting ‘cute’. Especially cute is the scene where Little Critter gives puppy a towel-dry and blow-dry, in which puppy transforms from a bedraggled creature into a fluffy pom-pom. The look on Little Critter’s face is one of great love. The setting of the Little Critter series is an American home housing a middle-class nuclear family somewhere between 1950 and 1970, when groceries came home in paper bags, when mothers stood at the sink washing dishes by hand in one-piece dresses with big bows at the back, when pets were sold from cardboard boxes. This is a cosy setting which only existed in America for a very short time, but it’s surprising how many picturebook creators are still making use of it. The cosiness of it is particularly well-suited to the picturebook audience, who receive much of their reading time right before bed.

In conversation with Katie Davis on the Brain Burps About Books Podcast, Mayer expressed his opinion on technology by saying that he bought a top of the line computer a long time ago (about 1990?) and hasn’t needed to upgrade since. I mention this because those of us illustrating picture books digitally are faced with a tough decision: Make do with cheaper software, or spend a disproportionate amount of money (relative to likely income) on Adobe CC. For those making do with older software on older hardware, Mayer’s opinion that you don’t actually gain much (if anything) by having the latest and greatest is worth hearing once in a while.

JUST ME AND MY PUPPY SPECIFICATIONS

First published in 1985 in the USA as a Golden Look-Look Book.

The Complete Mercer Mayer Collection (of Little Critter books — there are others) is a set of 24, available on Amazon

Oceanhouse Media made book apps out of the Little Critter series for the emergent reader market. The apps offer the functionality of word-highlighting, read-to-me and autoplay. Hotspots in the illustrations allow emergent readers to touch a part of the picture and hear the name of the object. But since these books were not created to be apps, they have not been coded from the ground up; rather, the pictures have been scanned in. There is little in the way of touch interactivity outside the pop-out words.

MERCER MAYER TALKING ABOUT PICTUREBOOKS

All three of my daughters loved Liza Lou and the Yeller Belly Swamp by Mercer Mayer, 1984. Picture book with strong young female in a cultural environment my girls found magical. We would take turns being the characters and they could participate even before they could read. It was the first book they wanted for there own children.

commenter from On Point

On the Brain Burps podcast, author/illustrator Katie Davis interviewed Mercer Mayer, whose Little Critter books were all around our house as I was growing up. My mother particularly enjoyed them. Sure enough, I enjoy reading them to my own kid.

The podcast can be found here (20 11 2013).

A Mercer Mayer board on Pinterest

Mercer Mayer has an astonishing work output even though he’s been in this biz since the late 60s, with over 400 productions by now. Mayer also interests me because many of the Little Critter books have been turned into apps by Ocean House Media. Here are some things I learnt about apps and children’s books from this interview:

Although many authors are reluctant to enter the digital age, he feels this is like saying of the Gutenberg Press, no I’m just going to stick to handwriting thanks. He sees no reason not to make works available via new technology, whatever that technology happens to be. Mayer’s attitude is not a new one — he also embraced CD-ROM when that was a thing.

Mercer Mayer has an assistant, Bonnie, who works with him on marketing appointments and on the more mundane Photoshop tasks which are nonetheless lengthy and time-consuming. While I thought this sounds awesome in a way, I wasn’t too impressed that Mercer Mayer didn’t realise Katie Davis is an author/illustrator in her own right. I don’t aspire to that kind of success — the kind where you don’t bother looking up your interviewers’ credentials, or keeping up with who’s who in publishing world.

Katie Davis at the time of this interview was considering biting the bullet and subscribing to the monthly plan that Adobe has now instituted for its Creative Suite. Mayer’s advice is to not bother. He still uses Adobe CS on Macs which haven’t been updated since Apple switched to Intel processors. He does update his printer, so it seems, because he was talking about how good printers are nowadays — he can get excellent proofs out of his. I think he has a point about the Adobe thing. While it’s nice to have the latest version, in fact it’s possible to do very good work with much older versions of this very nice piece of software, even if it takes you a few more keystrokes or whatever. Mayer no longer works on paper — it’s all digital — he uses a Wacom Cintiq (the top of the line model, by the way, in which it’s just like drawing on paper.)

Although Mercer Mayer has produced many books, each time he finishes he thinks that was his last work. But then he starts doodling and another idea presents itself. I’ve heard that the writer of Mary Poppins, P.L. Travers said exactly the same thing: Ideas are floating around in the ether waiting for a writer to pull them out of the air and turn them into something, and if you don’t do it, someone else will.

Mayer also says there’s no more than about 10 ideas out there anyhow. (Some people say seven.) It’s all about how you execute the idea.

The hardest parts of writing a picturebook are beginnings and endings. The middle is easier. The main problem with many middles is that the writer is focusing on the same scene for too long. You turn the page and it’s still the same scene, when the child reader wants to move on.

The other problem in many picturebooks is that the writer doesn’t seem to trust the illustrator, writing far too many words, perhaps as guides for the illustrations. Picturebooks are all about the illustrations. Illustrators who write their own stories don’t have this particular problem, and Mayer is thankful that he writes his own.